In the late '90s, Core Design's Tomb Raider Lara Croft had managed to supplant Indiana Jones as the player's adventurer of choice, leaving LucasArts somewhat in the cold.

As a result, Hal Barwood, the director of the 1992 adventure game Indiana Jones & the Fate of Atlantis suggested internally that the company should try to create a competing product to help make Indiana Jones more relevant to modern gamers.

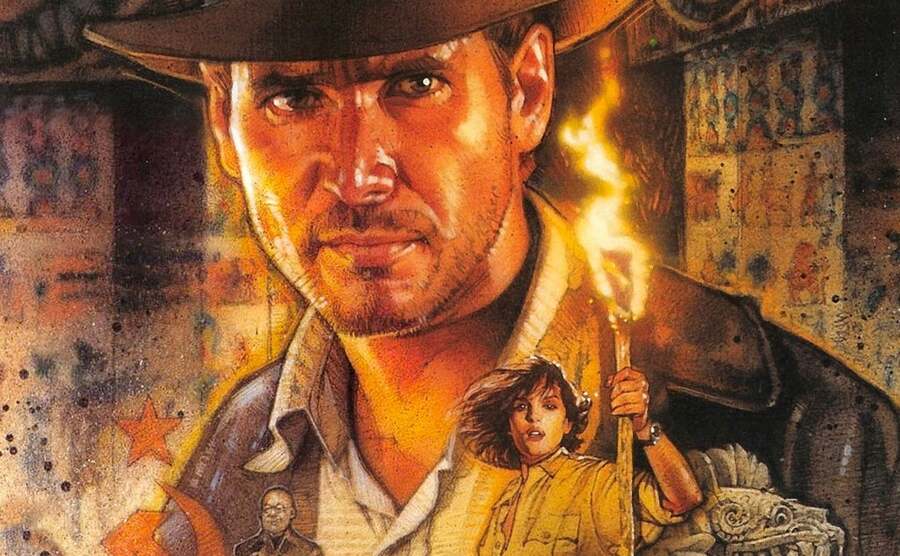

Indiana Jones & The Infernal Machine was released in 1999 for PC (an N64 version launched in North America one year later) and received strong reviews from publications like GameFan and Eurogamer, who praised it for its huge levels, excellent sound design, and immersive graphics. The game represented the first 3D installment in the Indiana Jones series and saw the team inside LucasArts wrestling with numerous technical challenges to pull this off.

With Bethesda Softworks and Machine Games scheduled to release their own take on Indiana Jones later this year — in the shape of Indiana Jones & the Great Circle — on Xbox Series X|S and Microsoft Windows, we thought it would be a great time to interview Barwood about some of his work on these old Jones titles as a designer/director. You can read the first part of our chat with Barwood covering his start at Lucasfilm Games & the making of Fate of Atlantis here. The following, meanwhile, covers the development of Infernal Machine and his eventual departure from the company.

Time Extension: How did the idea for the Infernal Machine come about? What were some of the inspirations for the game?

Barwood: So I played all of the Tomb Raider games – the early ones certainly – and I went to our studio management and I said, ‘Hey, we need to take our franchise back. These guys took it off from us and we’ve got to get it back. So I want to do a 3D Jones action-adventure game’. So they said, ‘Yep’ and that’s where Infernal Machine got going.

So part of the inspiration was just the fact that the guys that were doing the Tomb Raider games understood that you could take these ideas, which they got from Jones, and turn them into an action-adventure game. I just thought, ‘Wow, this is great and we should be doing it.’ The other inspiration was we had already done some 3D stuff in flight simulators and also Dark Forces. And we adapted the Dark Forces engine to do Infernal Machine.

Time Extension: In the past, it's been written that the original plan for The Infernal Machine was to focus on UFOs, but the idea was eventually vetoed by Lucas who wanted to save it for a film project. Could you tell us more about that design?

Barwood: I never got very far with my idea of an encounter between Jones and aliens. But a crashed UFO (maybe more than one) and possibly a semi-usable machine would have figured, along with an alien who escaped the crash. But no details were ever hammered out.

The veto came from the Lucasfilm exec, not George personally. But yes, you’re right, the Lucasfilm back office knew the veto was in favor of a future movie, but we didn’t learn anything at LucasArts; we were just told, “Don’t go there.” Nobody wanted to tip the company’s hand.

Time Extension: Why did you opt to go for The Tower of Babel as the replacement?

Barwood: Once it became clear that I could not do an ancient alien kind of story, we had to put on our thinking caps. A few ideas were tossed around, but none had any mythical heft, whereas the Tower of Babel and the entire city are famously cited in the Bible, and the Mesopotamian backdrop also had a pagan god we could use. I picked it, and no one objected.

Time Extension: You've said in other interviews that the team really struggled with the transition to 3D. Could you talk about some of the issues you faced working in 3D?

Barwood: Basically, because we were using Euler angles to locate everything we couldn’t do a lot of detailed stuff in 3D that you can automatically do now. So, for example, in most 3D games or certainly in the era where I was working and certainly afterward, you would have the world sitting there and it would look like you’re in that world, but actually, you’re constrained inside invisible walls so you can’t go behind a barrel and get stuck behind a corner.

Stuck plugs are a huge problem with 3D worlds so we didn’t do that. So we had to go crazy trying to make sure we didn’t have any stuck plugs. So it was just awful. But the main problem we had was with Indy. He’s going to move around a lot in a lot of different angles and you’re going to see him from a lot of different angles, and the problem is that Euler angles which just take three numbers to do a 3D position have the problem of gimble lock. If all the numbers come together, you can’t get back to the original. So we eventually found that we had to fuse Indy’s spine and you couldn’t move his torso independent of his hips.

That was okay, but then he also could barely use his whip, because every time he would crack that whip it would just turn into a knot. So we just had to be really careful about how we handled the whip because we needed to use that.

So we sort of solved it, but the thing is we were doing this on a PC, which is a pretty powerful piece of hardware relatively back then, and eventually, the company wanted to do what they called the rental Nintendo cart for the N64. Anyway, Nick Pavis, who was the guy they got to adapt everything, realized that he could just as we were assembling all of the material for the frame that we’re going to present, you take the Euler angles and you turn them into Quaternions, then you put that on the screen and you throw away the Quaternions and build them again for the next frame. The N64 was powerful enough to be able to do that. And it worked. And we never thought of it.

Time Extension: An interesting thing about The Infernal Machine is that you brought back Sophia Hapgood from Fate of Atlantis. Did you want that continuity between the two games? Up to that point, in the films at least, each one had introduced a different female protagonist.

Barwood: I think you’ve hit on something. A lot of the Jones character in the movies is actually a little bit based on, I believe, James Bond, who is a famous womanizer. In every movie and each book, Bond meets some woman and he beds her and has an affair, and then he's onto the next thing. Indiana Jones just did the same thing in the movies — though they eventually brought back Karen Allen (who played Marion).

I don’t like that. I was married for 60 years to my childhood sweetheart and it was a long and loyal marriage. I’m not very interested in characters who have wandering eyes and affairs, to be honest with you. So I didn’t want to do that. And I thought I need a character who can come and go a little bit in the games, but when I need someone to talk to I can have that person there, I can have that person help you, but they can get out of the way if we’re pressed to get our stuff done.

And so, I thought, I’ve got this shifty character from Fate of Atlantis who was a romantic interest in that game. I’ll bring her back and do the same kind of thing. Make her a shifty kind of character. And in this case, I gave her a reason to be shifty because she’s an intelligence agent in the CIA. So I thought that worked pretty well.

Eventually, there are cooperative puzzles that you need her help to solve and in a couple of cases, you have to rescue her, and she has to rescue you. It just allows for a wonderful way to incorporate dramatic elements into a game. And there’s kind of mystery to it all. She knows more than you do. I thought that was a really good way to run that story.

Time Extension: What are some of your strongest memories of the game? What are you most proud of today about the Infernal Machine?

Barwood: The main thing I think about when I think about Jones is I couldn’t play the game for many many years because I just thought those very few polygons got old very, very fast.

The hardware capabilities advanced very rapidly, especially in consoles, and pretty soon you could do an awful lot more with 3D than what we were doing. And so, Jones looked pretty old-fashioned as a 1999 game. But I played through it a few years ago again and I had a totally different experience because now instead of looking old and creaky, it just looked retro and I realized in the Jones Infernal Machine game, there are some of the very very very best levels or level design that I’ve ever experienced in a game ever. I just think they’re fantastic.

Now, were we doing it right? Well, first of all, George didn’t want to hire a lot of people who were experts because he wanted to not have to pay people too much, so we had a lot of people coming out of college and from tests, who decided to become level designers. So each level in that game took the person who was working on it about a year to get it in shape. We discovered after the fact that down in Insomniac when they were doing games like Spyro, they would do their levels in about six weeks because they had a lot more experienced people and a much better figured-out pipeline. So that was weird.

Nevertheless, creatively, I think the levels we did for that game, probably because they took a long time, were refined, and they exploited all of the visual possibilities. So I’m very proud of that game and I’m proud of the guys who worked on it. I just think they did a fantastic job.

Time Extension: Yeah, the Canyonlands level in particular has an amazing sense of scale and scope. Playing through it, that was one of the things that struck us most. Despite the "retro graphics", it was very easy to feel immersed.

Barwood: I had a very similar experience when we made the game, because you know, one of my favourite games is The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. And, eventually, in that game, you figure out how to win a race and acquire a horse and you can then gallop around this little world and sometimes you’re out in a field and sometimes you’re in amongst a bunch of trees with no underbrush, and even though it is very abstract and kind of primitive, you have that prickly feeling like you’re in that world.

I had the same experience replaying Infernal Machine, where I had the same feeling despite the abstract nature of a lot of the landscapes, you have this peculiar, mysterious feeling that you’re in that world. You feel very immersed in it. And I thought that was pretty darn cool.

Time Extension: After Infernal Machine, an external studio called The Collective was responsible for developing the next game in the series Indiana Jones & The Emperor's Tomb. What was the extent of your involvement with that game? Did you have much to do with it?

Barwood: The truth is I was nominally asked to consult about it. So they showed me the design docs and I was theoretically the company expert on Jones, so they wanted me to look it over.

This was being done by an external studio. So they came up with the story, not me. Though I am very interested in the Emperor’s Tomb and I certainly have driven by it – right there in Xi’an. I thought that was an interesting idea, but then again, somehow in China, there are a bunch of Nazis.

I thought, ‘What? This is crazy.’ I made my views known and I thought there were shortcomings. I thought it was rehashing a lot of material and not very interesting. My opinions carried no weight whatsoever.

Time Extension: And how long after that did you depart LucasArts?

Barwood: Pretty soon. I left LucasArts in October 2003. It was a mutual decision. They didn’t want me anymore and I didn’t want to be there anymore either. I had been working on a game for the PlayStation 2, and it was a very difficult game to get done because it was phenomenally difficult to program the PlayStation 2 and LucasArts had this high opinion of themselves.

It was a mutual decision. They didn’t want me anymore and I didn’t want to be there anymore either.

The management — in so far as they did manage – believed that we were a big company and we should be building our software. And the truth was we were a small to medium company and we should be buying our software. They were very slow to learn that. So we spent a lot of time with a talented guy who built us an engine to run the PlayStation 2, but it took forever. And I spent 39 months working on a PlayStation 2 title called RTX Red Rock about a special forces guy who are fighting aliens who have taken over a settlement on Mars.

Ultimately, although other people were taking a lot longer than me to get their stuff done, we couldn’t quite meet our deadlines, we went long, and the game was not a success and it soured LucasArts on me and it soured me on LucasArts. This was all happening around the time of Emperor’s Tomb.

Time Extension: Just as one last question, where can people find your work today if they want to keep up to date with what you're doing?

Barwood: They can either go to HalBarwood.com or Finitearts.com. Finitearts is my movie personal service company and it turned into my publishing company. And I’ll just tell you, nowadays I write books and the last one I wrote is a kids' book Why the Moon Makes Men Mad. So I recommend it! You can find out all about that on my website.