When it comes to recounting the history of video games, it's pretty easy to fall into the trap of funnelling everything through the American experience, from the rise and fall of Atari, to the emergence and overwhelming dominance of the NES, and the 16-bit console wars of the early '90s. But, to do this, ignores the fact that, for many in the world, their own countries' history of gaming was often entirely different to what was happening elsewhere, boasting its own unique tales of winners and losers.

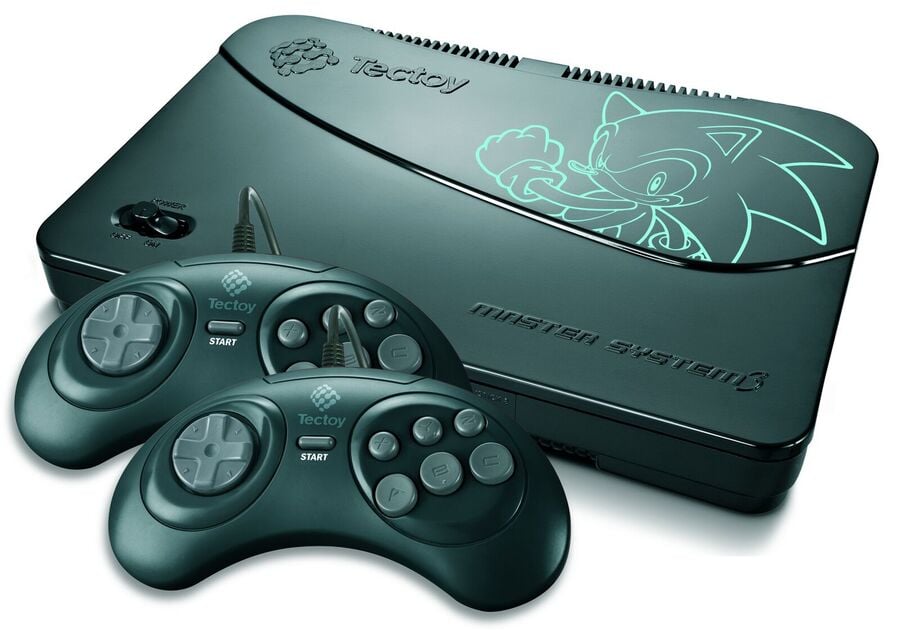

One of the most famous cases of this, for example, is in Brazil, where a company named Tectoy launched the Sega Master System in 1989 and miraculously turned the country into a nation of Sega lovers — so much so that the Master System is being sold to this day. This is a story that, admittedly, you may have come across before, especially if you happened to grow up in the country yourself or frequently watch Sega-specific YouTube channels that have likely touched on Tectoy in the past. But it's one we felt was worth looking into again, to hopefully provide a bit more clarity and context about the company's history and how Sega ended up dominating the market in Brazil.

We couldn't do this alone, of course, so we reached out to Stefano Arnhold, one of the earliest employees at Tectoy, to talk about his history with gaming in Brazil, the emergence of Tectoy in the late 1980s, and the incredible relationship the company ended up forming with Sega and its other overseas subsidiaries. And luckily, he was willing to offer us some of his time.

Arnhold, in case you're unfamiliar with him, has had a remarkable career in gaming. Originally joining Tectoy early on in the company's history, from the tech company Sharp, he helped launch the Master System and Sega Mega Drive in the country, before becoming CEO of Tectoy in 1994, following the death of the company's founder, Daniel Dazcal. This is a position that he ended up holding until 2019, which is when he decided to sell his stake in the business and move on to new ventures. You can read our conversation with Arnhold below, edited for clarity, flow, and length.

Time Extension: First off, it would be great to get some background on your history before Tectoy. How did you originally become interested in the video game market? Had you been interested in games before working with Sega?

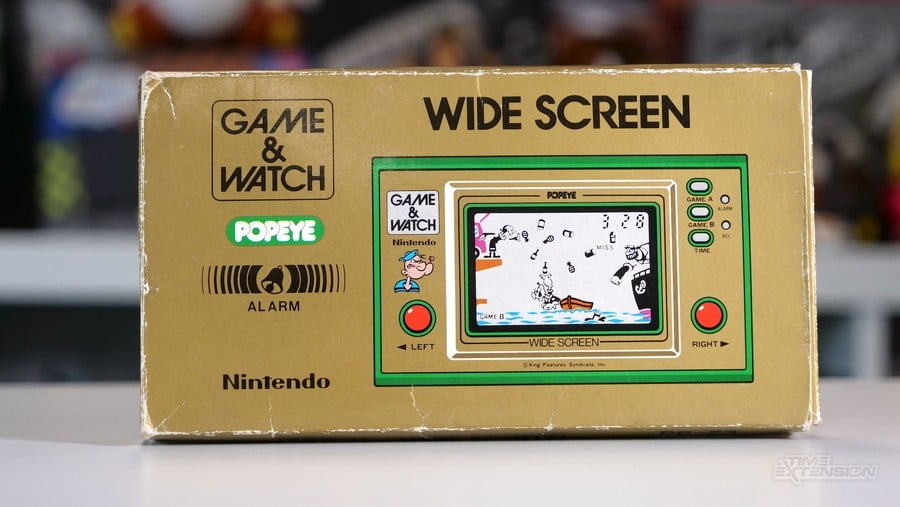

Arnhold: Yes. So, I’ll tell you the story. Before I joined Tectoy, at the beginning of the 1980s (possibly 1981), I had actually visited Nintendo in Kyoto while working with my uncle at a photography company, because I was interested in starting up a new business to manufacture and sell the Nintendo Game & Watch in Brazil.

Imports to Brazil at that time were very difficult, as the country had a lack of hard currency, so all the possible barriers for imports were there. But I had spotted an opportunity because my uncle's company represented a lot of Japanese companies, and one of them, a camera manufacturer named Minolta, was based near Nintendo in Kyoto.

I visited them and asked them to make an introduction for me, and, I don't know how, but I somehow convinced Nintendo to give me the rights to Game & Watch.

This final deal couldn't be done directly through Nintendo because of import restrictions. Instead, it had to be done through a trading company. The idea was that this company would literally disassemble the product, send the components to us, and the plan was to build a factory to reassemble it in a part of Brazil called the Free Zone of Manaus.

I thought that it was a great idea, but when I brought this to my uncle, he was not very eager to start the factory, because of the distance. I don't know if you know the geography of Brazil, but Manaus is pretty far away from São Paulo, which is where we were based at the time. Still, he was more or less inclined to go along with my plan until they told me that they needed a letter of credit. At that point, he said, 'No way. You cannot start a business with a company that doesn't trust you.'

I told him, 'It's okay, it's finance; no one trusts anyone.' But long story short, I wanted to do it; he didn't.

Time Extension: And is that why you decided to go and work for Sharp?

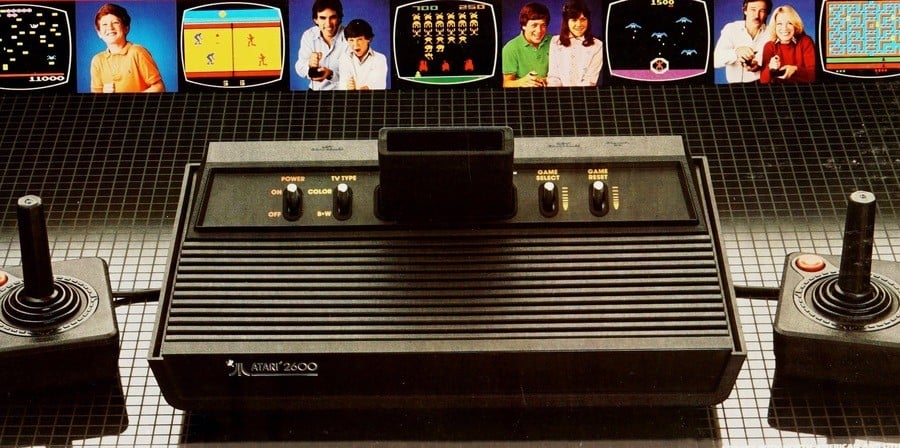

Arnhold: Correct. Sharp was interested in manufacturing the Atari 2600 in Brazil, and a friend of mine said to me, 'I see that you are unhappy. Why don't you go talk with Sharp?' And so, I moved from my uncle's company to Sharp's strategic planning division to try and do the Nintendo Game & Watch idea there.

Sharp in Brazil at the time was a very big organisation. It belonged to a Brazilian entrepreneur who was very politically connected. So it was one of the 50 largest economic groups in Brazil. We were also leaders in colour TVs, which at that time was a big business. Unfortunately, though, we didn't end up getting the rights for the Atari 2600, because Atari was sold to Warner, which is a big media group that still exists today.

Warner was pretty much the king of the universe then. You basically had to kneel in front of them to get a deal. So, they were completely out of their mind with what they were asking. But another Brazilian company, Gradiente, accepted their terms. And instead, we went to Mattel and got the rights for the Intellivision. As for the Game & Watch, Sharp told me it was simply 'too small' a market, and they didn't want to enter minigames, so again, I couldn't do it.

While at Sharp, however, I met an individual named Daniel Dazcal, who was the industrial director and then later the vice president of the whole Sharp division. I went to work with him directly as his marketing director, but then, around March 1987, he left Sharp, if I’m remembering correctly, which led to him starting Tectoy.

I was not actually at Tectoy on the 18th of September when the company was originally founded, but I came 15 minutes later. Daniel wanted me to stay at Sharp first to do the things he couldn't do, but he knew that I had a huge interest in video games, so eventually, he invited me to join him at the end of the year.

Time Extension: With Tectoy, how did games become the main focus? Was that just from the offset that you wanted to get into console distribution? I've also heard of another company, Daniel Dazcal founded, called Elsys. How does that figure into things?

Arnhold: Elsys was the first company that Daniel founded when he left Sharp. It's actually still around today.

Originally, he was developing ASICs, which are basically small microprocessors built for a specific use, and he was analysing different businesses that had products that he could potentially use them in. The first company he found was one called Whirlpool Brazil, which had recently bought a huge operation called Brastemp. They were the leaders in washing machines, refrigerators, and in what we call White Goods.

Working with them, Elsys replaced the heavy metallic mechanism for the washing machine's motor with a very small PCB that was maybe 10-15 square centimetres and weighed just a few grams, with zero investment, and after that, Daniel began looking at other new areas to invest, including the electronic toy (and video games) market.

In Brazil, at the time, there was a company called Estrela, which later teamed up with Gradiente to bring Nintendo to Brazil, and Estrela had 55 per cent of the electronic toy market, so it was the absolute number one. It also had 50 years of history, while Elsys had zero years and zero market share.

So when Daniel looked at Estrela, he said, 'Why should we help Estrela? Why don't we do it ourselves?' And that's where the idea of Tectoy comes from. He knew that I had ideas in this area, so this is how I was chosen to join.

The main investors were the Chris brothers, who owned Evadin, which was Mitsubishi TV at the time in Brazil. Not as big as Sharp, but not a small enterprise, because they were quite big in TV sets here in Brazil.

Time Extension: At Tectoy, you started in a marketing position. Could you tell us how you eventually became CEO?

Arnhold: Yeah, so I came to work with Daniel, and he was, of course, our leader and an inspiration to everyone.

He had more of an engineering and industrial background, so everything which was engineering and industrial was with him. Meanwhile, when I joined, I was joining in more of a, let's say, administrative or financial role. So, I was working in those areas, but also doing marketing because it was the thing that I liked the most, which was developing and launching products. In the beginning, job titles didn't mean much to me, because we were doing a lot of different roles. But when Victor Blatt came to join us, we needed official names, so I became, I think, the vice president of new business, or something. That was the name I got.

Unfortunately, though, in 1994, Daniel passed away from cancer. So, to keep the company going, my family helped me buy his shares and take over control from the Chris family.

Time Extension: When people bring up the story of Tectoy's relationship with Sega, they often mention a lightgun toy called Zillion, which was the first collaboration between the two companies. How did Tectoy get involved with distributing that toy in Brazil?

Arnhold: We approached Sega and said, 'Look, we are who we are, etc, etc. We want to do your video games.' And they made a noise, like 'No way, that's not gonna happen'. So what we did then was rather than give up, we proposed that we'd start with toys instead.

The toy division of Sega was struggling. So the general manager of the toy division said, 'That's a great idea. I would love to sell Zillion to Brazil.'

But again, we could not agree to import the finished product. We had to assemble it ourselves, and we had to buy all the components, make the moulds and so on. So what we did was we concentrated all the efforts of our small company in that one product and tried to make Zillion a big thing here in Brazil. In the end, we sold many times more Zillions in Brazil than they sold worldwide.

Time Extension: It must have been a pretty big risk to put so much of this new company into this one product. Was there a huge anime following in Brazil at the time?

Arnhold: I think it was more the other way around; we were helping more people discover anime.

We had chosen really good people from Sharp, so it was more about the people we had. I dare say that this team could do whatever it wanted. So we were all focusing on, what can we do to make this work? We even went to Rede Globo here in Brazil, which is a huge TV station — one of the largest in the world — to air the TV series. So even if anime was not mainstream, I believe a potential market for it already existed.

As well as Zillion, we also did another product not long after, which we licensed from Video Technology, VTech, in Hong Kong, which was called Smart Start, or Pense Bem in Portuguese, and it went super well. It was Toy of the Year. And I consider that our first success. It was much larger than Zillion. And it was one of the best-selling electronic toys in Brazil until today. We also sold much more than VTech worldwide again. It was at that point, we returned to Sega and said, 'Now you know who we are. Please. Give us the Master System.'

Time Extension: How easy was it working with Sega? Again, you had to get the components from them to reassemble the Master System in Brazil. Was it easy to convince them to share information with you?

Arnhold: I think we were very lucky because Samsung wanted to carry the Master System in Korea at the time. Samsung is not a small company, but like us, it also couldn't import the console outright and would have to get the components.

So someone inside Sega suggested, 'Why don't we try this out with Tectoy?' Because then we will have this knowledge, which is not easy knowledge to come by, and we can later do business with Samsung.' So Tectoy could be the test.

We made the deal, but I think, after that, they then immediately realized that we were quite a strange company because the talent that we had was unbelievable. For instance, one of our guys, who was the main guy from Elsys, Mr Victor Blatt, was a genius in the microprocessor area, and he would often talk with the technology directors from Sega about the Master System.

I think they were wary of us because they had thought we were just these crazy guys in Brazil, how did we know all this stuff about their technology? Or they suspected maybe somebody was leaking information to us. But there were also others who would say, 'Come on. These guys are brilliant.' So I looked at it like it was sort of a love-hate relationship on their side. Our main contact was with a guy called Chiaki Tofusa-san in international sales, who was working mainly for us. He also had two assistants who worked with him. But we also talked to everybody there, from the president Nakayama-san to Sato-san and the overseas coordinator Shimazaki-san.

Time Extension: When you launched the Master System, what was the landscape like for video games in Brazil? What was Nintendo's presence like, for instance?

Arnhold: In the beginning, we weren't actually fighting Nintendo. We were fighting Nintendo clones backed by big companies, like Gradiente and CCE.

At that time, CCE was larger than Sharp in Brazil in electronics. And they were doing clones. So their cost was ridiculous. But we beat them. Why? Because we looked at the whole picture. We had the games. We had the hotline. And we had our newsletter, the Sega Club. We also did a lot of market research, too. We visited Sega Europe and Sega of America, for example, and we learned a lot, especially from Sega of America. They told me something that I'll never forget. They told me, 'You have to capture the schoolyard gossip. Once what they talk about in the playground is your game, you're done. That's what you have to capture.' And we did.

Time Extension: How soon after the launch of the Master System did the idea of internal development start? Developing your own versions of games or creating your own original games.

Arnhold: That happened later on, out of pure necessity. We launched the Master System in '89, and then in '1990 we launched the Mega Drive, but the rest of the world was already in 16-bit at that time.

So when we were preparing for our TV commercial for the launch of the Mega Drive, we had the same idea as the rest of the world, that 16-bit is much better than 8-bit. That's the way to go. But the kids were mad with us. They told us, 'Hey, don't launch anything. I just spent six months convincing my father to buy me the Master System, and you're going to launch a new one. That's not gonna work.' Because of that, we did not promote the Mega Drive as a substitute for the Master System. We launched the Mega Drive as a new piece of technology targeted at more advanced users.

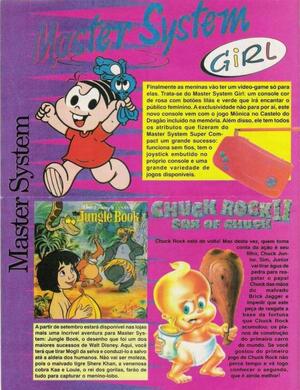

And so, because we were doing new consoles and new versions, we desperately needed new software to keep the Master System going. There was one moment when I probably knew 100% of the released 8-bit Master System games worldwide. I could tell you who the producer was and who had the rights, because I knew all of them. But we also had to invent some things ourselves. That's when we said, 'Let's try Brazilian characters.'

We took Wonder Boy and changed it to Mônica, which is very, very popular here, and that was a huge success; we converted games from Game Gear; and we also did a game for Woody Woodpecker that was developed entirely from scratch, because we found out that Woody Woodpecker in Latin America was the character with the largest number of licensed TV episodes. We even did our very own version of Street Fighter II.

Time Extension: A story that often comes up in regards to Tectoy is that the company was important in Ayrton Senna being the star of Super Monaco GP II (a game released for both the Mega Drive and Master System). Can you talk about how you pitched Sega on Senna? What was their initial response to the idea?

Arnhold: We were nudging Sega with new ideas every day, and the answer was normally no. We were like their little brother, 'Can I go to the movies with you?' — 'No'. 'Can I go with you and your girlfriend?' — 'No'. That's more or less what it was like. And sometimes we even went through with the idea, even though they had told us not to, because we knew we needed it.

But when we came to SEGA with the idea about Senna, they knew him already and responded, 'Ahhh, sou desu ne, sou desu ne' (そうですね, そうですね), which meant they agreed with the idea. The Sega vice president Shoichi Iramajiri was also there, and I think he had just arrived at the company. Before that, he was a vice president of Honda, where the racing division had been below him, so he was very instrumental in the sense of everything coming together.

As for the development, it was handled internally by Sega of Japan, but we acted as the interface between engineering and the driver. Senna was an absolute perfectionist. And he brought his perfectionism to the game.

For instance, he told us, 'I don't like the way you treat the zebra because in the game, when we go over the zebra, you lose points and you damage the car, and that's not true'. He said, 'We use the zebra all the time, we have to, as a support. Only if you go on top of the zebra with the full wheel, then you're gonna damage the car. So we need to change this.' We would go and tell Sega, 'Please make this change,' and they would say, 'No, that's too difficult,' but Senna would say, 'No, you have to do it because you want my name in your game.'

Time Extension: You mentioned before about Sega saying, 'No' to you a lot. Are there any ideas that you can specifically remember that you pitched to Sega and they just outright refused to do?

Arnhold: I can give you one: the black and white video game. Game Boy was huge, and Sega at the time had the Game Gear, which ate through, I don't know how many Batteries, but it was still a fantastic product.

Playing Super Monaco GP II game to game with two Game Gears was always an amazing experience, and you could even use the Game Gear as a TV set. So we thought it was fantastic, but we knew it would never hit the millions that Game Boy was enjoying, especially in Brazil. So we found one company in Taiwan — I don't remember the name — that had this product they were interested in selling. Their product was okay, but I went to my head of engineering, Roberto, and said, 'The audio is lousy. Can you fix it?' And he said, 'Sure, no problem, but it will cost a little bit.'

So we came more or less to the idea that if we could do half a million units, it would pay for the investment. That was the ballpark figure we had in mind. So I went to talk to Randy Rissman, who was the owner of Tiger Electronics, which had excellent distribution, especially in the U.S, and I said, 'Now imagine if this has Sega games,' and he said, 'This looks pretty feasible.' Everything seemed to me to be pretty positive, but then I flew out to Tokyo, and I had a very bad meeting with Sega. They told me, 'No way,' but this time they said it convincingly, so I knew I couldn't do it. They said, 'No, Sega will never have a monochromatic handheld.'

We tried to explain to them the size of the market we were aiming for, and asked, 'Let us just do it in the US & Brazil.' But they told us again, 'No'. In other words, don't even think about it.

Time Extension: How complicated were the games going to be? Were they going to be like actual Sega games, like the Master System or Game Gear? Or even more simplified?

Arnhold: They were going to be real video games, not LCD games. If you put them side by side with a Game Boy, they would be, let's say, Game Boy-like, but for our games: Altered Beast, Golden Axe, Afterburner, Sonic and the whole library, right? I think it would have been a huge success. In my opinion, there was no chance of failing.

Time Extension: Have any prototypes survived? Or do you have any images of what it may have looked like?

Arnhold: No, we kept it really, really secret. In the beginning, we didn't want anybody to know for obvious reasons, but then, when Sega was so determined not to approve it or license their games to us, we more or less got rid of everything to do with it. We didn't want this to leak because, after many, many years with an excellent relationship with Sega, we knew exactly when we could advance with something like this and when we could not. So I think it was an excellent idea, but they said, 'We don't want it, it won't happen,' so we thought, forget it, let's try something else.

Time Extension: Speaking of hardware, in 1993, you did make a wireless version of the Master System called the Super Compact. This was then followed by a special variant called the Master System Girl, specifically aimed at younger girls. How did the idea of making a console specifically for the female market originally come about?

Arnhold: In our research, we saw that more or less eight to nine per cent of the console owners were girls, but the number of girls who were actually playing was double or three times that: between 20 to 25 per cent.

When we interviewed girls to find out why, they'd say, 'I play at my cousin's house, I play at my brother's,' and we said, 'So you don't own one?' And they would look at us and say, 'Why should I own one?' So that gave us the idea to come up with the Master System Girl. We went to Mauricio de Sousa, who is the creator of Mônica, and we said, 'Mauricio, what if we do a female-directed Master System, would you help out?' And he loved the idea. So we were basically trying to capture and transform the girls who were already playing into console owners.

Time Extension: In hindsight, do you feel the problem with the Master System Girl was the idea or the execution? Was there any way you could have perhaps executed the idea better?

Arnhold: I think it was just too early. Girls played games, but they didn't want to own them back then. Of course, there were exceptions, and we did increase the number of girl owners from eight to ten per cent, or something like that. But it didn't pay off as well as we were hoping. So it was another idea to add to the list of things we were a little too early on. In Portuguese, we have a saying that it is human to make a mistake, but it is a big, big mistake to make it again. But at Tectoy, we made many mistakes.

Time Extension: So far, we've mostly talked about the Master System, but in 1995, you also launched Mega Net, an online service for Brazilian Mega Drive owners. How did that come about? Also, did you ever consider carrying Sega Channel instead?

Arnhold: We tried to get the rights to Sega Channel, but eventually couldn't get it because it was very complicated. But if you remember, we had the Sega Club, which was our newsletter.

Sega Club had more or less 230,000 active members. And to send out newsletters, it wasn’t easy. I remember when we were still small, like 20,000 or 30,000 members, we had to stop the whole office, and we were putting the stamps on the envelopes, because it was such a huge operation. So, our view with Mega Net was, number one, we wanted to reinforce the community sense of those Sega Club people through direct communication with us through Mega Net. And then, number two, we wanted to provide other things to do, like home shopping, home banking, and real-time head-to-head gaming.

We also thought that it would help us communicate to customers, ‘Don’t buy Nintendo, buy Sega’, because with Sega, you'll be connected with us in the fantastic new world of computers.

As for why we did banking, you have to remember that in Brazil, inflation was very high, so our banking technology was (and is still to this day) one of the best in the world. Everybody was writing checks because you could not go out with money on the street, so the banks had to have the infrastructure to compensate for taking zillions of checks all on the same day. Bill Gates would even come to Brazil every time he launched a new package for banking systems, because it was such a big deal. And so, this was an environment from which we came.

For us, we worked with Banco Bradesco, which is the largest or the second largest private Brazilian institute, and we proposed to them the idea of home banking with the Mega Drive, which they loved. At that time, telephone lines in Brazil cost a small fortune. Like maybe between three and five thousand dollars for one line. But we offered them a slightly different system.

Instead of being connected to their server 100% of the time, we made a different system in which we connected for 16 seconds, transferred all the information, and then disconnected. You want to give back; it would take another 16 seconds, send it back, and cut again. They also helped us a lot with it because they had fantastic technology at that time, and knew what they were doing. But unfortunately, it was a bit too early. I don't know if you saw, but we did a commercial for the Atlanta 1996 Olympic Games. We licensed a country song here in Brazil that everybody knows, but we changed the words to it.

The lyrics were more or less 'Don't give your love to him, give it to me', because it was a love song. But we changed the words to 'Don't send an email to him, send it to me'. We hired five athletes. All of them got medals in Atlanta '96, and we put computers in the Olympic village in their dormitory, and it was a huge failure. Nothing happened. When we went to interview people about why the commercial failed, despite us spending a huge fortune, we found out that a lot of the people in Brazil didn't know what an email was. So, it was definitely too soon.

Time Extension: We’re curious, how long did this service last? Also, was it difficult disconnecting people from it when the time came to shut things down?

Arnhold: It was very difficult because we were using a frame relay connection. Frame relay was a direct line, quite expensive, a very good connection, and very low latency.

We were offering the people, let's say, one cartridge, two cartridges, 100 cartridges, and negotiating individually. There was one guy in Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre in the very south of Brazil, and he said, 'No way, you're not going to disconnect this. I'm going to sue you. I do all my faxes through that. I live on Meganet.'

We told him, 'I'm sorry, we have to disconnect. We cannot afford to maintain it, right?' Finally, one day, he gave up. But it was tough.

Time Extension: In the 2000s, you started releasing new versions of the Master System with the games built in instead of relying on cartridges. Could you talk a little bit about how you came to that decision to abandon software sales?

Arnhold: It was a matter of necessity. When we made that decision, software piracy was unbelievable, and you also had emulators starting to become popular, too. So it came to a point where we were selling virtually zero Master System software, and we had to live from the console.

So the formula of adding value to the console became a necessity. You had to add in more games, so we put in, I don't know, 20 games, 21, 32, and now they have 131, if I'm not mistaken. That means, today, if you want to give a kid a console to start playing video games, you have 131 excellent games to play with straight away. Well, not all 131, but at least 60 of them are going to be great, right?

So it was always about necessity. We were finding out what we could do next every day to keep the Master System going, and asking Sega, 'Can we do it?'

Time Extension: In 2019, you decided to sell Tectoy. Why did you choose to sell the company after so many years in charge?

Arnhold: It’s simple; I needed capital. We had very big financial troubles in 1997 with the crisis in Asia. Interest rates in Brazil exploded. Only the real part of interest with inflation, not the whole interest, was something like 42% in November 1997, and we still had a huge debt because we grew really fast, and decided to leverage rather than get capital, which was a mistake.

Eventually, we reduced a lot of our debt, I think from 75 million dollars to 35 million — I don't know the exact numbers — but we nearly went bankrupt in the process. It took several years, and by the end, all our capital was gone. So suddenly, we entered the 2000s with Sega abandoning video game consoles, and as I said, we also had to live on consoles, not on software, because of things like piracy and emulation. We tried DVDs and other stuff to make a difference, but it was not exactly our field. So what I was always looking for was somebody who would have the capital necessary to give Tectoy and Sega that new push.

Then, in 2019, I found this gentleman who was very big in the world of small banking terminals in Brazil, and who liked video games a lot. He told me he would buy the company if I took it private. So it took us some time to take it private, and he bought it at the end of 2019.

Time Extension: Do you miss it at all? Being involved with Tectoy?

Arnhold: Yes and no. I do miss it, but I don't really have much time to think about it. By the time I sold Tectoy, I had already gone very deep into sports governance. I now work a lot with the FIS, the International Ski and Snowboard Federation. I've also opened a new venture builder, called CBKK (Celo de Bonstato Kaj Konservado), in the environmental area. Through that, we are opening new businesses, and we also have a research institute.

I'm still working, I don't know, maybe 15 hours a day, or something like that. So I don't usually get much time to look back on everything we achieved.

Time Extension: Thanks for your time, Stefano. We appreciate you taking the time to speak to us.