Mario, as we're all aware, is one of the most successful and instantly recognisable video game characters of all time. He's starred in more games than you've had hot dinners and, via these escapades, has racked up combined sales of around 400 million copies – as well as spawning spin-off franchises with massive sales figures of their own, such as Mario Kart and Mario Golf. However, while Mario has headlined more than his fair share of classic adventures – Super Mario World, Mario 64 and Super Mario Odyssey to name but three – he doesn't boast a totally perfect record, and one of his most questionable outings has to be Mario is Missing, an educational title from 1993 that, even to this day, elicits a vitriolic response from many players.

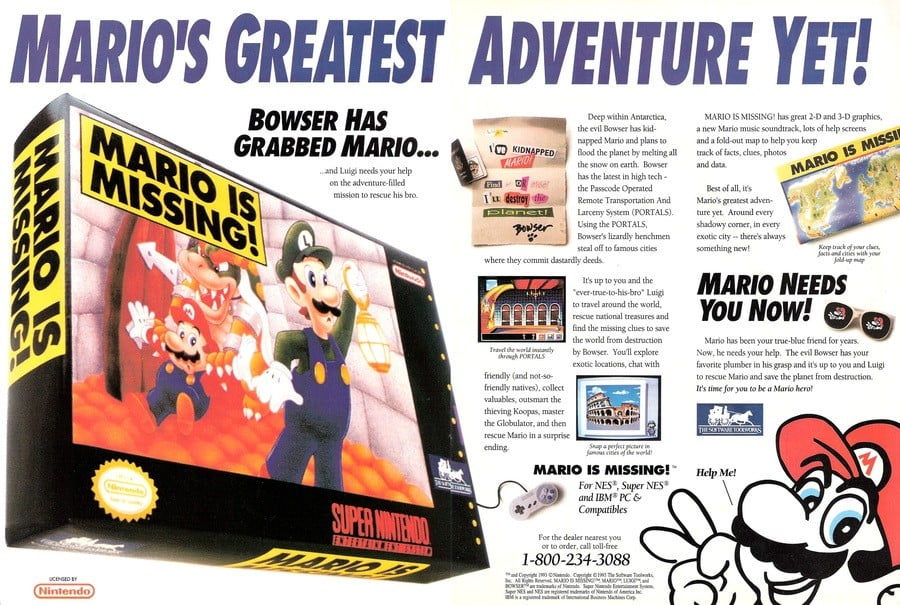

To make matters worse, as the title implies, Mario isn't even the true star of the game, which was released on MS-DOS, NES, SNES and Apple Macintosh. The player instead controls his brother Luigi, marking his first significant starring role outside of the 1990 Game & Watch LCD game Luigi's Hammer Toss. His quest, as the title suggests, is to track down his more famous sibling by travelling around the globe to return various stolen artefacts and ultimately rescue Mario from the clutches of the evil Bowser.

Created by The Software Toolworks – famous for its 'edutainment' titles on home computers – Mario is Missing arose thanks to the company's pre-existing business relationship with Nintendo, which included the expensive but critically lauded Miracle Piano Teaching System for the NES, which taught children how to play (you guessed it) the piano. "Toolworks had enjoyed good success with Chessmaster, Mavis Beacon Teaching Typing, and The Miracle Piano Teaching System," explains Donald W. Laabs, the lead designer on Mario is Missing.

As Laabs explains, Software Toolworks had one major rival at the time, and the company saw Nintendo as the critical tool in winning the war. "We wanted to compete with the Carmen San Diego series by Broderbund. At the same time, we had an early relationship with Nintendo and had developed Chessmaster titles for the NES and Game Boy. To compete with Carmen San Diego, it was thought that a licensed character like Mario would carry a lot of weight. One of our new execs had an excellent relationship with Nintendo of America and was able to secure a licensing deal for Mario edutainment products."

One of our new execs had an excellent relationship with Nintendo of America and was able to secure a licensing deal for Mario edutainment products

Laabs reveals that the team at Software Toolworks was made up of avid Mario fans. "Most of us had played and enjoyed a lot of Mario games on various platforms. In fact, because we had development systems, we were able to play the Japanese versions of Mario games before they were available in the US. We were surprised to learn that Yoshi was called 'Yoshi.' We called him 'Dude.'" Jeff Chasen, who programmed the MS-DOS version of the game, explains that it wasn't a job that was taken lightly. "I had played Mario on various platforms. We were all excited to work on such a well-known character, and we felt privileged that Nintendo allowed us to build Mario is Missing."

Nintendo was clear from the outset that it wanted an educational title, and therefore left Software Toolworks to its own devices – after all, that was the company's area of expertise. The Japanese giant was primarily concerned with making sure the characters looked right. "They were very interested in the look of the Mario characters," explains Laabs. "Our lead artist was required to travel to Japan to attend 'Mario Art School' to learn how Mario characters should be presented. On the other hand, we were the first non-Nintendo studio to be granted permission to do a Mario title on a console." This, as Laabs readily admits, was a huge deal. "It wasn't clear that Nintendo of Japan fully realized what the Nintendo of America deal committed the company to," he adds. "Nintendo of Japan did not want us to do a game that might be confused with a traditional Mario game."

While it was a great honour to be given a chance to work with Mario and his friends, Laabs admits that he and his colleagues were under no illusions about their chances of matching what had previously been created by Shigeru Miyamoto and his staff at Nintendo. "One of the reasons that Mario games were so amazing was – and probably still is – that the multiple competing game teams and the hardware teams work hand-in-hand during development. Hardware considerations inform game design decisions, and game design considerations inform hardware decisions. In the end, the game and the platform are perfect for each other. We were never going to be able to match that." Even so, Chasen reveals that the Mario is Missing developers still referred back to the 'original' games whenever possible. "The design team and the engineering team continually looked at other Mario implementations for inspiration," he says.

For those customers who expected a traditional Mario game and got an educational game, the console versions upset people more

While traditional Super Mario games are famed for their wonderful accessibility, they're still capable of posing a welcome challenge for skilled players – something that, as an educational title, Mario is Missing would have to avoid if it wanted to appeal to its target audience of very young children. Ultimately though, the obsession with beating edutainment rival Broderbund was a key motivation when it came to creating the ideal design and interface for the game – rather than mimicking a Mario outing.

"The dev team was intent on competing with Carmen San Diego, and we hired the Carmen game designers to work on our design team," Laabs says. "There was a lot of push-pull between company factions that wanted a Carmen San Diego competitor and those that wanted to fully leverage the Mario license with traditional Mario action-based elements. But Nintendo's guidance was clear: don't make it look like a traditional Mario game." Chasen concurs, adding that much of the team's attention was on its direct rival and not what Nintendo had done previously. "We did spend a lot of time looking at Carmen San Diego and its design and trying to balance that out with what we knew about Mario. We tried to find the balance between keeping it true to Mario and ensuring it delivered its educational promise."

Mario is Missing was initially coded for MS-DOS and released at the start of 1993, with the SNES title coming later alongside a NES port coded by Radical Entertainment. Each title is slightly different, not just in terms of content but also in appearance; the SNES version, for example, takes audio and visual cues from Super Mario World. As the design lead, Laabs was responsible for all of the variants of the game. "All of the Mario is Missing teams reported to me, so if there's stuff people liked or didn't like about the game, the buck stops here," he says. "There were things that worked better on one platform or another, and each Mario is Missing version sold enough to easily recoup the investment. For those customers who expected a traditional Mario game and got an educational game, the console versions upset people more."

The main criticism of Mario is Missing is fair: that it was packaged and marketed as a traditional Mario Game, and it wasn't

Given the game's currently standing, it's easy to overlook that, at the time of release, Mario is Missing not only helped Software Toolworks generate $7 million in profit for the second quarter of 1993, it also kickstarted a series of Mario-themed educational releases which would include Mario's Early Years: Fun With Letters (1993), Mario's Time Machine (1993), Mario's Early Years: Fun with Numbers (1994) and Mario's Early Years: Preschool Fun (1994). The game also garnered some positive reviews; one of EGM's writers gave it a score of 8/10, while rival publication GameFan compared it very favourably to the aforementioned Carmen San Diego series. However, the overriding critical reaction was negative, with other magazines lamenting the slow gameplay, lack of action and disconnection from the wider Mario series.

Over time, the game's reputation has taken even more of a nosedive – a fact which thankfully hasn't kept Laabs awake at night. "If you want to be in the game business, you're signing up to have your work both admired and maligned," he says. "Even the products I worked on that were significant critical and commercial successes, like Chessmaster and Sims 2 Expansion Packs, inspired many detractors. That having been said, the main criticism of Mario is Missing is fair: that it was packaged and marketed as a traditional Mario Game, and it wasn't. We were worried about this at the time, but the ability of game communities to communicate with developers and publishers in 1992 was nothing like it is now, and none of us would have predicted in a million years that 27 years later, people would still be documenting the missing diacritics and debating about how the Eiffel Tower would fit into a suitcase."

Despite the negative legacy attached to the game, Laabs has very fond memories of its production. "For me, it was an honour to be able to work on Mario titles, and we had a lot of fun. I'm tickled that it still remains a topic of conversation all these years later. I would say that I'm significantly happier about Mario is Missing than George Lucas is about the Star Wars Holiday Special."

Chasen shares this sentiment. "As Don says, it was honestly just an honour to work on such a key title at a time in the industry when there was a focus on leveraging tech and gaming to build educational titles. I suppose I can understand some of the criticism if you approach it from a pure gaming perspective. When you approach it from an innovation perspective, and trying to create a new way for children to learn, you do need to have taken risks – which we did. It was just really fun to be part of the adventure."