Derbyshire lad Chris Sorrell has come a long way since pounding the streets of Matlock in the '80s. He's worked with the likes of Millennium Interactive, SCE Cambridge and Radical Entertainment, and has had a hand in creating world-famous video game franchises such as MediEvil and James Pond.

But there's one title which Sorrell remains almost inexorably linked with, more than 30 years after its release: James Pond's second outing, Codename Robocod. Originally released in 1991, this cute, colourful and incredibly playable 2D platformer is one of those unique breed of games which continues to be released in some shape and form right up the present day; the PlayStation 2 and Nintendo DS both received ports, and even the Nintendo Switch and PS4 have received their own versions.

Sorrell is a disarmingly humble and modest individual, and one who doesn't take effusive praise easily. He entered the industry at the tender age of 16, teaming up with programmer Steve Bak after running into him in Alfreton's Gordon Harwood Computers, where he was then gainfully employed. "Steve was looking for a bitmap artist to help on a new game, and I was super keen to get my first break into the industry," Sorrell recalls. "I spent a week putting together a set of example images and was lucky enough to get the contract for the 16-bit editions of Spitting Image, which was based on the popular satirical puppet show of the period. Afterwards, Steve decided to set up Vectordean and in the space of a year, we had worked together on Dogs of War, Fire & Brimstone and Bad Company – for all of which I just provided the visuals."

Not content to work solely on the graphical side of things, Sorrell dearly wanted to be more intimately involved in the process of designing and creating a video game. "My first break was to do an ST and Amiga conversion of an old game that Steve had written on the C64 called Hercules, which was slightly re-themed to become Yolanda. It all went well – or more precisely, I did everything that was asked of me – and I guess I earned the freedom to come up with my next project, which was codenamed Guppy."

By this point, Vectordean was working with publisher Millennium Interactive, and the two became almost inseparable. "All business dealings were completely between Steve and Millennium," say Sorrell. "However, since Millennium was originally just three or four people and initially had no in-house development, I got to know everyone very well and we had a few fun meet-ups where we would take stock of progress and talk about new ideas."

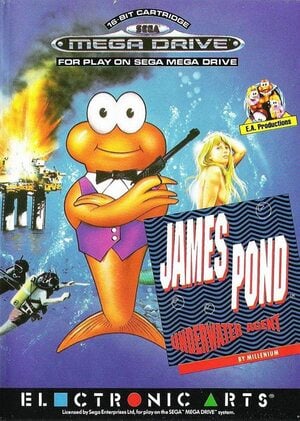

It would be during one of these meetings that Sorrell's project would receive its iconic title. "Millennium's managing director Michael Hayward had the 'so bad it's good' idea to re-name the fishy star of my in-progress game as 'James Pond' – which of course we latched right on to and ran with." Released in 1990, reviews for James Pond: Underwater Agent were positive if not ecstatic and it performed well enough for a sequel to be mooted – a game which would comfortably eclipse its predecessor in terms of critical and commercial success.

"There was very little external direction or expectation as to what form it would take," Sorrell says of the development process. "I think everyone was pretty pleased with how James Pond had come together and I was given complete freedom to build the game I wanted to build. For James Pond 2, it seemed to me that we should try to continue the spoof theme whilst also moving in a direction that could genuinely offer new gameplay potential. This principle went into the design 'mixing pot' along with a desire to make a more pure platformer, and to be more ambitious technically now that I was starting to know the Amiga pretty well."

Never one to let a good pun slip through his fingers, Sorrell came up with the game's famous moniker himself. "The name 'Robocod' just popped into my head one day, probably because I had recently watched the Paul Verhoeven classic. It seemed perfect, not least because it gave us the opportunity 'to rebuild him', and was just a ludicrous and ridiculously appropriate premise to build the game around."

Despite the success of the first James Pond escapade, Vectordean was still very much a grassroots studio, and Sorrell found himself labouring away in a less-than-desirable working environment. "In the earliest days, Vectordean was based out of Steve's spare bedroom, but when we moved 'up' it was into an equally inauspicious location – a dingy upstairs room that was part of a dodgy-looking used car lot. We had to squeeze past second-hand BMWs and touched up old Rovers just to get into work each morning. It was one of those semi-permanent wooden-panel kind of buildings with no heating or hot water – definitely not the most fun place to be on a winter's day."

I was still working on some of the graphic sets anyway, so incorporating a Penguin wrapper into the candy set wasn't a big deal, nor was getting a little Penguin guy drawn up by Leavon Archer, who worked with me on some of the visuals

Unlike James Pond: Underwater Agent, Robocod would be a traditional platformer. A keen gamer for some time prior to entering the industry, Sorrell was able to call upon a vast amount of experience when crafting the mechanics behind the game. "I had always been a big fan of platformers, right from my very first computer – an 8-bit Atari, playing Miner 2049er obsessively – and through my time on the C64, which was spent on the likes of Trollie Wallie, Ghosts 'n Goblins, Monty on the Run and especially Thing on a Spring. There was also Rainbow Islands and Great Giana Sisters on the Amiga. All of these games – along with brief but memorable childhood visits to arcades playing Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., Ghouls 'n Ghosts – certainly had a big influence on me."

Robocod is also notable for being one of the first video games to feature product placement; McVitie's Penguin chocolate bars were incorporated into the game, despite Sorrell's initial reservations. "That started as a purely business thing," he explains. "I don't recall if it was a done deal that we had to implement or a 'strong suggestion' for something that we should include, but either way, it was something we weren't exactly thrilled about, not least because it represented extra work to be done within our very finite development period. Fortunately, at this point, Simeon was comfortably on top of the Mega Drive version and had enough free time to work on the new intro. I was still working on some of the graphic sets anyway, so incorporating a Penguin wrapper into the candy set wasn't a big deal, nor was getting a little Penguin guy drawn up by Leavon Archer, who worked with me on some of the visuals."

Sorrell soon found himself warming to this new element. "It was obvious that it only added to the general kookiness of the game. I'm glad they let us have a little fun with it, like the way on the Game Over screen the penguins drag off Pond and it says 'Smoked Kipper for tea!' – credit to Simeon for that! It's funny what a memorable trait of the game it all became."

However, it was the emergence of powerful Japanese gaming hardware which would have an equally dramatic impact on the evolution of Robocod. "Around the time I was working on the original James Pond I bought an import Mega Drive and fell in love with Mickey Mouse: Castle of Illusion; there are definitely hints of that in Robocod," Sorrell explains. "I also became aware of Mario for the first time; Nintendo wasn't really big in the UK, and certainly not part of my gaming experience until the SNES. Partway into Robocod, I bought a Japanese Super Famicom, and Super Mario World became my instant all-time favourite game. By this point, I think we were fairly set on our path with Robocod, so I don't recall borrowing anything too directly, but undoubtedly the sheer quality of Super Mario World became an attribute I very much aspired to achieve in our own game."

My approach to that was to make Robocod really play to the Amiga's ability to fill backgrounds with eye-popping colour gradations and unusual parallax effects. These fitted the cute levels perfectly in my opinion, and left the Mega Drive version of the game feeling somewhat flat by comparison

Despite his newfound fixation with console platformers, Sorrell's prime system was undoubtedly the Amiga. Having honed his coding skill during the preceding years, he felt supremely confident with Commodore's popular home computer, and Robocod was released during what was arguably the platform's golden era. "1991 was definitely an exciting time to be working on the Amiga," he says. "It debuted a few years earlier in its expensive initial form, but now the cheaper A500 was out and selling big, and people were starting to figure out how to get the best from its powerful but somewhat quirky hardware. Biggest of all for me was that the system's market share was becoming large enough that a game could 'lead' on the Amiga without having to be reined back in order to make a decent ST version."

Sorrell's affection for Commodore's computer wasn't so ardent that it totally blinded his judgement, and he admits that by the dawn of the '90s, the hardware was being outpaced by systems which had the advantage of being designed specifically for playing games. "A bitmapped screen was great for showing pretty title pictures, but sucked too much power when it came to scrolling and rendering lots of sprites, overhead that the tiled screens of the consoles didn't incur," he explains. To counter this, he decided to focus on the Amiga's strengths. "My approach to that was to make Robocod really play to the Amiga's ability to fill backgrounds with eye-popping colour gradations and unusual parallax effects. These fitted the cute levels perfectly in my opinion, and left the Mega Drive version of the game feeling somewhat flat by comparison."

Although he was concerned with making the Amiga edition the definitive version of the game, Sorrell was well aware of just how important the Mega Drive port would be. As was the case with the original game, Electronic Arts had stepped forward to publish on the Sega Mega Drive, and this version was therefore developed in parallel with the Amiga offering. "Our relationship with EA was certainly a little strange," Sorrell recalls. "James Pond was the first Mega Drive game to be developed in Europe and was produced in a crazy rush on a one-of-a-kind Mac-based dev kit that Steve had to personally fly back with from San Francisco. Robocod was more straightforward; still using that same dev kit, we had a dedicated Mega Drive programmer called Simeon Pashley working on that version as well as assisting me with bosses and the game's intro. For this one, we continued to deal directly with EA folk in California, sending them update builds each night very slowly via 28k modem."

Ironically, the slightly tighter development window for the Sega version actually resulted in Sorrell and his team being able to add even more polish to the Amiga iteration. "Our contract with EA actually gave us a month less development time, so even though it wasn't the 'lead' platform, we had to ensure that the Mega Drive had a very clear focus throughout development. The upside to this was that once the game was essentially complete, I had a month of time to do nothing more than add polish to the already complete and tested Amiga edition. That is a rare luxury in game development, and one that definitely allowed me to make the Amiga version a better and more personally significant version." Robocod would also find his way onto other formats of the period – including the SNES, Game Gear and the ill-fated Commodore CD32 – but Sorrell wasn't involved with any of these ports. "All other versions of the game were developed or commissioned directly by Millennium," he says. "I was always sorry to have not had the chance to work on the SNES version – it would have been great to throw in some Mode 7 gimmicks."

Somehow he'd go away, having taken it all on board, and working within those totally unreasonable limitations, come back with something wonderful. As soon as those insanely catchy Robocod tunes showed up on a 3.5" floppy disk one day we knew that Richard had just given us something that would become a real hallmark of the game

Sorrell considers himself extremely fortunate to have been able to work with the late Richard Joseph not only on the game's music – built around an infectiously catchy pastiche of Basil Poledouris' iconic RoboCop theme – but also the soundtrack to the other Pond outings. "In each case, he came to visit us and we'd spend a day going through the project, discussing ideas for musical cues, listing the dozens of sound effects we wanted to hear, and then we'd confess that we only had some paltry amount of memory spare for him to work with – just 28k in the case of Robocod," Sorrell remembers.

"Somehow he'd go away, having taken it all on board, and working within those totally unreasonable limitations, come back with something wonderful. As soon as those insanely catchy Robocod tunes showed up on a 3.5" floppy disk one day we knew that Richard had just given us something that would become a real hallmark of the game." Joseph – who also worked on the likes of Speedball 2, Gods and Chaos Engine with the Bitmap Brothers – sadly passed away in 2007 at the age of 53 after being diagnosed with lung cancer.

Remarkably, James Pond's most famous outing was crafted in just nine months, but despite this short space of time Sorrell is adamant that there is little he would seek to change, given the chance. "For the time and scope we had, I think Robocod – especially that Amiga version – achieved as much as I could have hoped for. I would have loved to have made it a 'bigger' game – more abilities, more gameplay diversity, more genuine depth – the kind of stuff that was wowing me with Super Mario World. It still astonishes me how we managed to make a game as reasonably credible as Robocod in just nine months, with only rudimentary and often self-created tools, all in unforgiving assembly language on a platform with a tiny, tiny fraction of the power of a modern smartphone. These modern kids don't know how easy they've got it with their integrated development environments, Gigabytes of RAM and fancy shading languages!"

Upon release, Robocod received almost unanimous praise, not only from magazines like ACE which largely concentrated on computers, but also from console-focused publications like Mean Machines, which awarded the game a glowing 95 percent rating and stated emphatically that it was the best platformer on the Mega Drive. "I was only 19, so I definitely felt excited and exhilarated to see such a positive response," Sorrell admits. "I especially remember the ACE review making a flattering comparison to Mario and contrasting Nintendo's huge team with our own humble team size; quite an ego boost. Having said that, I was certainly under no delusions that Robocod really was better or even remotely in the same league as Mario. But – quite dangerously – it did make me feel that maybe with the next one we really could hit that quality mark. Of course, this a recipe for the kind of overreach that can so easily blight game development, and lead to a far bumpier path for James Pond 3."

We worked for a while on James Pond 4: The Curse of Count Piracula, but eventually shelved it. I was lucky enough to get another of those 'creative freedom' opportunities and came up with MediEvil

Robocod's success resulted in a Track & Field-themed spin-off by the name of Aquatic Games before Sorrell began work on final entry in the trilogy. 1993's James Pond 3: Operation Starfish clearly shows the influence Super Mario World had on Sorrell's creative outlook, and this time around lampooned Sci-Fi hero Flash Gordon. "Things changed significantly for James Pond 3 as we were now dealing with EA people based in the UK and I was working on the Mega Drive as the lead platform," Sorrell says. "We ultimately had our associate producer renting a local bedsit so he could work all hours with us on-site to help build levels and test the game – a bizarre experience for us and him, no doubt." Despite favourable reviews and solid sales across both home computer and console formats, the third game isn't as well remembered as its illustrious forerunner.

Sorrell's next move was a geographical one, as he departed Vectordean and moved from Derbyshire to Cambridge to work directly for Millennium. "We worked for a while on James Pond 4: The Curse of Count Dracula but eventually shelved it. I was lucky enough to get another of those 'creative freedom' opportunities and came up with MediEvil." One of the 32-bit PlayStation's most popular titles, this 3D action romp drew a healthy dose of inspiration from Capcom's Ghouls 'n Ghosts, a personal favourite of Sorrell. "There were quite a few trials and tribulations on that as we initially worked on a range of dubious platforms in a quest to find a publisher, eventually seeing fate smile on us as we landed a deal with Sony – and subsequently became a Sony studio. It's probably no coincidence that Robocod and MediEvil are easily the most memorable things I've worked on, and were also the most fun times of my career."

Amid the tension of getting Robocod finished in such a short space of time, Sorrell thankfully found time for lighter moments. He inserted a dedication to his then-girlfriend Katie – to whom he is now married and works with at Spoonsized Entertainment in Canada – into the final game. "Within a hidden bonus room, there's a parallax background formed from hearts containing mine and my future wife's initials," he explains as a cheeky schoolboy grin covers his face. "Katie even stumbled across the room without any prompting, which was a nice bonus."

Sony purchased Millennium in 1997, renaming it SCE Cambridge Studio (last year it was rechristened Guerrilla Cambridge). Sorrell worked on Playstation 2 titles Primal and 24: The Game in 2003 and 2006 respectively, but by the time the latter hit store shelves, he was once again keen to stretch his legs and try something different. "Me and my wife ended up moving to Canada as I joined the team at Radical Entertainment working on Prototype," he recalls. "Of course, by that time, pretty much no one was getting to make their 'own' games any more, so I was content to focus on programming. By 2011, having witnessed Activision systematically dismantle a once awesome studio and feeling the itch to be more creative once more, I decided to go solo. I always aspire to make the best things I can, so I never wanted to make 'just another' forgettable iPhone game."

There are clearly businessmen who see no shame in porting an old game to a modern platform and pretending it has some timeless magic making it worth a modern gamer's time and money, but it sure embarrasses the hell out of me even when I have no part in it

While Pond's second outing has been re-released on various formats throughout the years, the only all-new adventure we've seen since 1993 is the 2011's largely awful iPhone title James Pond and the Deathly Shallows, produced by HPN Associates without any input from the original team. However, in 2013 there came the exciting news that the secret agent would be getting a proper resurrection – and one which would involve Pond's creator himself.

A Kickstarter campaign was initiated by the current IP owner Gameware, and Sorrell was drafted in to lend some credibility to proceedings. The venture was cancelled before it got anywhere close to its £100,000 funding goal, and has clearly left a sour taste in Sorrell's mouth. "There's such a fine line between what makes for a valid Kickstarter project and what simply feels like 'First World begging'. But I was contacted by PJ – the guy tasked to coordinate the campaign by Gameware – and he had some convincing arguments. Build a new game that rewards loyal Pond fans, make amends for the sorry state of the franchise in recent years, have the chance to get paid to work on a new Pond game. Those all sounded like good enough reasons to lend my support. Most of all I definitely had a feeling that if it's going to happen anyway, then I should probably be involved to try and make sure that the new game really does live up to the promises and doesn't end up short-changing fans, again."

Sorrell was apparently being prepped for a creative director role in the event of the funding target being met, but it soon became clear that his role was exaggerated in order to draw support from fans. "Gameware were all too happy to let this be seen as my campaign when it wasn't," he laments. "We weren't nearly well enough prepared with the kinds of materials necessary to sustain a successful campaign and I couldn't personally spare the time to do much about that. Also, it turned out that the ownership of the IP wasn't as clear-cut as I believed it to be – and was in fact a matter of some acrimony. As I now understand it, Gameware own the rights to the James Pond character and to any new James Pond games, but System 3 own some specific rights to Robocod. It's rather confusing and something I would liked to have known prior to the Kickstarter campaign. I was sorry to see the campaign fall flat, and certainly sorry to feel like we had let down the people that cared most about James Pond."

To make matters even more confusing, at precisely the same time Gameware's Kickstarter went live UK publishing veteran System 3 announced that it would be rebooting Robocod for modern consoles. "I've never had any interaction with people from System 3 regarding their reboot of Robocod," admits Sorrell. "I suspect they were just trying to spoil the potential success of Gameware's Kickstarter campaign whilst probably also using the whole thing as a litmus test of whether they should even consider such a product. There are clearly businessmen who see no shame in porting an old game to a modern platform and pretending it has some timeless magic making it worth a modern gamer's time and money, but it sure embarrasses the hell out of me even when I have no part in it." Back in 2014, CEO Mark Cale was adamant that the reboot would happen, but after more than a decade, nothing has been seen or heard of it.

A remake is one thing, but there will be those fans who crave a new adventure. 2013's abortive Kickstarter has done much to sully the name of Pond, and has cast some doubt over the feasibility of a totally fresh instalment. Do moments such as these make Sorrell ever wish that he had ownership of the franchise and thereby ultimate control over its future? "It would be nice, if only to have blocked some of the awful ports," he responds. "But no, it's not something that really makes me bitter or sad; I was very lucky to have had someone paying me to make games I wanted to make. Perhaps a juicy bonus cheque or two would have been nice – I got one £3,000 bonus after Robocod's launch, but that was the sum total of the riches I ever saw from Pond – but at least on the Vectordean and Millennium end of things, I knew all of the people involved very well and I don't believe anyone was personally getting rich at my expense, just investing money into more projects with often little to no payback – such is game development."

Is there any chance for Pond to bounce back when so many other '90s icons have faded into obscurity? "I definitely think that with the right creative drive – and money – it would be possible to make an excellent new James Pond game," Sorrell asserts. "It would have to try and capture the quirky charm of the original or Robocod, and not overreach like we did with James Pond 3 and not wallow too deeply in nostalgia. It should be a game designed to win new fans and in doing so remind original fans why they might still remember it fondly. Ideally, it would be like if Nintendo hadn't made a Mario game since Super Mario World and then came back with Super Mario 3D World!

"If someone wants to fund that, then I'd love to be a part of it, but realistically, I don't see that happening. I might also grudgingly admit that a smaller-scale, slightly retro Pond reboot could be cool too, if handled by the right people. However, I would absolutely prefer for there never to be another Pond game than see the IP further sullied by any more weak, half-hearted efforts."

This feature originally appeared on Eurogamer and is published in an updated form here with kind permission.