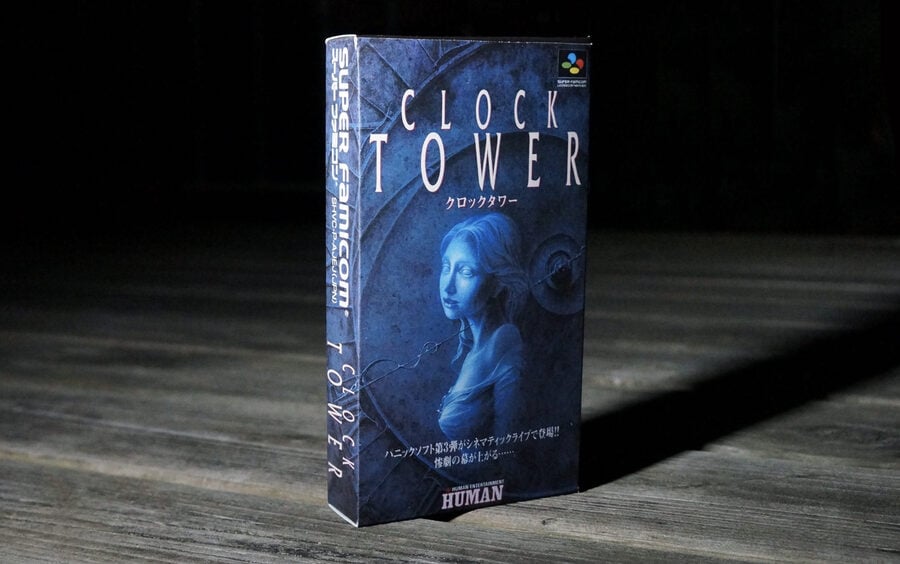

Given the recent announcement of an enhanced port of Clock Tower by Limited Run Games, we naturally wanted to examine the original's creation and chat with its creator, Hifumi Kouno.

Released on the Super Famicom in 1995, it is an important thread in the tapestry of the survival horror genre. Of course, by this point, the genre was already well established, with numerous proto examples throughout the 1980s (Project Firestart on C64 is a fantastic example). It was also after Alone in the Dark but, importantly, just before Resident Evil mania took hold.

We've now mentioned three other horror classics which defined the genre – consider that each of them, despite placing the player in danger, also allow them to fight back. Of all the horror games predating Clock Tower, few made the protagonist quite so vulnerable (Nostromo, 3D Monster Maze, and Ant Attack just about fit the template). This makes it a precursor to later titles such as Amnesia and Alien: Isolation, where players need to hide from rather than engage the danger.

"People around me said that a game where the protagonist runs away from the enemy would not work," says Kouno in his online biography, reflecting on nearly 30 years. Adding, "It was my first original title at Human Entertainment, and one that paid homage to one of my favourite film directors, Dario Argento."

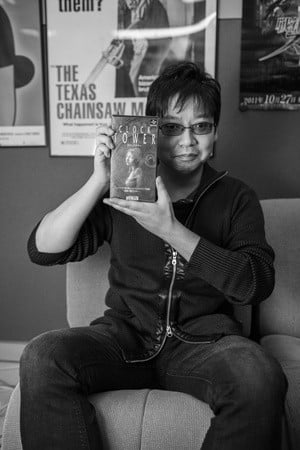

We spoke to Kouno several years ago as part of the Untold History of Japanese Game Developers project, and as we sit in his office, his love of film is apparent, the walls adorned with framed posters for American History X, Blues Brothers, Dark City, A Clockwork Orange, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. An interesting mix of comedy, horror, and the darkness of the human psyche – as the interview goes on, there's the impression that Kouno immerses himself in all mediums of creativity when searching for inspiration. He also shows humility, since we've just caught him in a mild fib. Clock Tower was not quite his first game at Human; it was actually as director on F1 Pole Position 2.

"That was about six months after I joined," he admits, "Since Human was producing so many titles they didn't have enough directors, and they asked for someone to volunteer. So I raised my hand and took the position. I also directed Human Grand Prix 2 and 3. I don't put those on my biography because really they are Ryoji Amano's games. Essentially, I just made some updated versions. We weren't at the company at the same time, but I have respect for him."

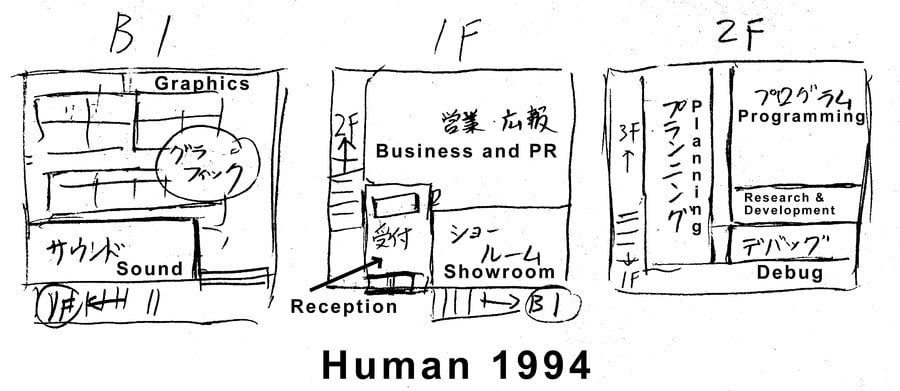

So with a few "updated" games for experience, Kouno finally had the chance to create his own original game. As he describes Human Entertainment at that time, most projects were handled by five-person teams. With one major exception, "The exception was Fire Pro Wrestling, which had about 20 or 30 people. Human had a number of different teams working simultaneously. Clock Tower had a seven-person team, as I recall."

We ask for a sketch of Human Entertainment's offices, to get a feeling of what the atmosphere was like. To our surprise, Kouno and colleagues from the time draw a map showing that the graphics and sound staff were kept in the basement, while the planners and programmers were on the first floor (2F in US and Japan). Debugging was also on this upper floor, but the split within individual teams is surprising.

Given the doubts certain colleagues had about the game's concept, we wonder if having a small team, in conjunction with the company focusing on its flagship wrestling series, afforded Kouno some leeway. Specifically, we ask him how he overcame the doubts and remained focused.

"It would be cool of me to say that I simply followed my convictions without wavering!" he laughs. "But that would not be true. I have doubts of my own. But, when I write a game proposal, I simulate the total game in my head in detail, to the point where I can mentally play and see it unfold in my mind. When the game in my head is fun, I know that the real game will also be fun, as long as I follow the design in my head. That gives me the inner confidence to proceed."

The game's story centres around a group of orphans who go to live at what they believe is an idyllic mansion in the woods: the Barrows Mansion. As one expects, things go horrifically awry with the appearance of "Scissorman" – a diminutive demon-like figure brandishing oversized scissors and with a penchant for murder. The protagonist is Jennifer Simpson, resembling and named after the character of Jennifer Corvino (played by Jennifer Connelly of Labyrinth and Requiem for a Dream fame), a homage to Dario Argento's film Phenomena, which Kouno is a fan of. It's up to Jennifer to explore the mansion, collect items, avoid getting murdered by Scissorman (who pops up throughout to scare the hell out of you), solve the mysteries of what he is (and her own orphaned past), defeat the evils within, and ultimately escape. If you can – there are nine endings with various outcomes, plus game over if killed.

Although Kouno admits to being inspired by Argento, the actual model for Jennifer was a little more local. "For the creation of character graphics, we photographed an actual person," he explains, adding that they then, "imported it, and made it into CG, a technique that was in vogue at the time. The motion actress for Jennifer was a lady I worked with in the planning division. After explaining the concept of the title, she did a wonderful job, including hanging from a projection above the entrance to the roof terrace and stumbling in the hallway. Most of the motions in the game came from her acting." This would likely be Yasuko Terada, credited as "main cast" in the game, and also as a director on other Human Entertainment titles.

Mechanically Clock Tower plays similarly to a point-and-click adventure, with an icon moved with the D-pad and hotspots to click on. Various buttons on the controller act as quick keys, stopping Jennifer, cycling the inventory and so on. Notably, the L and R buttons cause Jennifer to run in that direction, lending the game a more direct feeling of control, and essential when Scissorman appears. Running, however, depletes Jennifer's health. It can recharge through various means, including just sitting down in a safe place, but this mechanic adds a delicious tension to proceedings.

"One of the fundamental concepts of the project was not simply to add a horror theme to the game design, but rather to apply horror films to the game system itself," Kouno explains. "In horror films, it would be strange to see the heroine running indefinitely. At some point, she'll run out of breath and be unable to run, and you feel a sense of crisis as she risks becoming trapped. So the game mechanics came about by trying to make the game seem real."

While the icon-driven interface may imply suitability for use with the SNES mouse, we can't imagine not having L/R available as emergency panic buttons to flee in a hurry. Even if doing so drains health and may ultimately kill us. Had Kouno considered mouse support, we wondered?

"The problem was that the mouse peripheral had a low install base," explains Kouno. "Optional mouse support would have been good, but making the mouse required to play the game would have created difficulties from a business perspective. Another thing is that the original Clock Tower was quite an experimental project that did not have a large budget or development staff. So we didn't have the extra resources to include mouse support. We also had to cut the map down significantly for the Super Famicom version."

This leads us to the work of the fan community, and the fact a patch has been made to allow mouse support, in addition to fan translations into various languages, since it never left Japan. "I'm impressed that there's a fan translation," says Kouno, who then asks, "Do you use an emulator to play it?"

This feels a little awkward, since, by its nature, emulators necessitate the use of ROMs, which in many cases means not purchasing a game. We tread delicately, explaining the legalities of patches, and how the Aeon Genesis team spent nearly two years working on it, starting in 1999 and finishing in 2001. Kouno's response soon dispels this awkwardness.

"Wow!" he exclaims, "That's really impressive! It truly makes me happy to know that some people are willing to do all that to play it. That's a lot of work! And sometimes, the old games were programmed in a very unusual way, depending on who wrote it. It would be nice to release them, though. As for myself, I talked to a certain publisher about doing a reboot or a re-release of Clock Tower, but they didn't agree to it, because horror games are difficult to market." (Ironically, when we reconnected with him recently, Kouno was unaware of the forthcoming re-release of the game.)

This belief by publishers is surprising, especially given the success of survival horror in recent years, especially those which eschew combat in favour of player vulnerability. We list various titles, citing Amnesia as a game which perhaps owes a certain heritage to Clock Tower.

"Oh yes, I've heard of it. It's on Steam," nods Kouno, aware of the market. "There was also Alan Wake, and the Silent Hill series is still going. But if you make a proposal for a big-budget horror game on an HD console, no Japanese publisher will go for it. They might agree to a horror-flavoured FPS or action game, but not pure horror."

Despite such resistance from publishers, Kouno managed to break through when he created NightCry. Released in 2016, and funded through Kickstarter, it was a traditional point-and-click survival horror, very much like Clock Tower. Reviews were mixed; negative reviews lamented how antiquated it felt compared to modern titles, and a lack of polish; the positive reviews, of which there were many, enthused about how unapologetically old-school it was, feeling very much like a new Clock Tower instalment.

"This is the game I've been dying to make," Kouno says of NightCry. "[Clock Tower's] combination of unique gameplay where you are only able to run or hide from enemies and the point-and-click interface was well received. I've really wanted to make another game like that."

Whether it's Clock Tower, Steel Battalion, or Infinite Space, the games of Hifumi Kouno are distinct and polarising. They're a unique flavour which some will not enjoy, and that's perfectly OK – because there are equally as many fans of his work. The topic of meeting player expectations versus one's own goals is a deep one, and we ask for Kouno's views, referencing his many fans outside Japan.

"I have a lot of overseas fans? I wasn't aware of that," he says humbly. "How much should you adapt your work to the market, whether it's the domestic market or the overseas market? If you ignore that question altogether, and just create what you think is fun, you will find at least some measure of success. This was the case for me with Clock Tower and Steel Battalion. So sticking to your own ideas in the face of market expectations can result in good games. On the other hand, when thinking in terms of being successful as a business, you may struggle if you don't take the market into account. In my case, Clock Tower sold fairly well, but the difficulty is in striking that balance between the business side and the creative side."

Finally, we ask Kouno to pose for photos, naturally holding the game we've been discussing all afternoon. We also ask if it was given to him, or did he have to buy it?

"I bought it with my employee discount," he reveals. "People making games are rarely given a copy. But we had an employee discount to buy games within the company, and that contributed to the total sales of each game. So most of us were happy to buy our own copies. I think most developers probably buy copies of their own games, but don't play them. You have to play your game many times over during the debugging and test play phase, so by the end of the project, you've lost interest in it. I actually played Clock Tower recently. <laughs> My girlfriend wanted to play, so we played through it together."

We can't think of a nicer sentiment to end on than that. So we'll leave you with Kouno's words from our previous news story: "I am a creator, and I am fully committed to creating new works of art!"

Long may he continue.

This article was created using a combination of interview material from The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, and recent correspondence with Hifumi Kouno.