Initially getting his start back in the mid-80s, the LA-based producer, designer, and project lead Antonio "Tony" Barnes has been making games for almost four decades now.

During that time, he has understandably managed to be involved with the creation of a lot of great games, having worked at a wide variety of companies such as Electronic Arts, Crystal Dynamics, The Collective, and Double Helix.

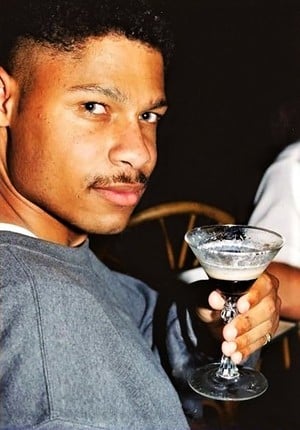

At Electronic Arts, for instance, in the '90s, he would end up being one of the key individuals involved in creating the design for the company's Strike series of games, and even made a cameo in a couple of the later games in series, lending his likeness to the character Agent Ego (A.K.A Antonio Scott). In addition to that, he also notably worked on Double Helix's 2014 reboot of Strider as a design director, being an integral figure in coming up with that game's direction and story.

Whereas many game developers with a résumé such as his would typically love talking to the press, Barnes only occasionally stops to do interviews with members of the media, preferring to put all of his focus into his work. Nevertheless, we were able to convince him recently to sit down with us over a video call, to discuss some of the games he worked on, leading to a discussion about how he first got started in games, his time at EA, and a few of the standout titles he has in his back catalogue. During this chat, he shared with us a bunch of fascinating stories, from his original plans for the cancelled Super Strike Trilogy for the Sega CD, to his memories of working on the best Buffy the Vampire Slayer game ever made and the other Capcom classics he wanted to revive following the release of Strider (2014). You can read our conversation below (edited for clarity and length):

Time Extension: How did you originally get into the games industry? Could you tell us more about your origins as a game developer?

Barnes: I started making games in the sixth grade when I was 11 or 12. They stuck Apple II computers in schools and I was fortunate enough to be in a school that had them, growing up in the Bay Area.

I was super poor. I had no money or anything, but luckily the teacher just kind of let me roll with using them. And the reason I was using them was because it was faster to program a pixel to cross the screen than it was to coordinate a team to do stop-motion animation, which is what I was trying to do. I was trying to become Ray Harryhausen and make something like Clash of the Titans.

Fast forward a few years and I was messing around, making some games for the other kids at school at age 15, and I noticed that the game submissions in magazines like Antic and Compute had started to kind of take a nose dive — probably because a lot of the people that I really liked were getting hired by companies and stuff. So I made three games in about two weeks and walked into the offices of Antic, handed them to the receptionist and she handed them to the editors who looked at them and said, 'Wow kid, do you want a job?'

After that, I started working for Antic in publishing, as the transition from the Atari 8-bits to the ST and Amiga happened. It was there that I would end up learning how to produce games by interacting with third-party developers or people from other countries, while also making my own games on the premises. I was also the sole customer service/tech support for GFA basic, GFA assembler, AMOS, and STOS for the Atari and the Amiga, because Antic had published those in in the US, but they had no dedicated tech support for them. That led to me learning how to debug code over the phone. Those were the beginnings, I'd say, of my professional career, around 1987.

Then, later on, in either 1988 or '89, I had graduated high school and was in college for film and television and I just started thinking to myself 'Why am I going to school for a thing that I'm kind of already doing?' I wasn't doing film or television, but I was already doing video games. So I got out of college and since then, I've been a full-time professional in the games industry.

Time Extension: How did you initially end up getting the job at Electronic Arts? Do you remember the interview process at all?

Barnes: Growing up in the Bay Area and being a gamer, there were certain places that I had always wanted to work at — Electronic Arts, Broderbund, and LucasArts. So it was always on my bucket list of things to do. And it eventually ended up happening, because of a friend of mine called Greg Thomas.

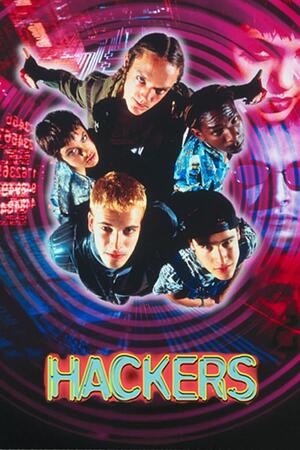

So when I was working at Antic, I would often leave work and I would go to a local bar when I was only 16 or 17, and the bar was kind of like something out of the movie Hackers. So it was this weird mix of goth and cyber wear. And it was just my local place. Anyway, one night, I was sitting there with a case filled with 3 ½ floppies for the Amiga, and this guy sits down next to me and he's got a torn up leather jacket, a bike chain for a collar, a black beret, and he just looked like an extra from a Billy Idol video or something — or Mad Max.

Anyway, he asks me, 'What are those for?', pointing at the floppies. And I'm like, 'Here we go!', because even today, when I say I make video games, it's this weird record scratch in the world. So I told him I worked in games and he said, 'Oh really? I do too' and he whips out this Epyx badge, and it turns out he was working on the Epyx handheld that later became the Atari Lynx. He was a pixel artist, and he actually did the art for California Games, Electrocop, and a few other games.

Anyway, we talk some more, his friends come over, and his friends and I are big Prince fans, so we immediately become buddies. And that group turned out to be from Visual Concepts. So, the people that I met that night were Scott Patterson, Greg Thomas, and Matt Crysdale. Speaking to each other, we all realized that we had kind of a similar vibe — we all started in the demo scene and had a certain attitude towards gaming — and we even developed a pact where we would work on each other's games for a while and [recommend each other for stuff].

Fast forward from there and I am having my first set of twins (because I have two sets of twins) and I need more than a little job or contract work doing ports. So my buddy Greg calls me up and he points me to Britannica Software and I worked there for about a year. That was 1990. Then in 1991, he calls me up again and says, 'Hey, I'm working with Electronic Arts. They need someone that understands design, knows how to code, and it would be great if they did some pixel work too. Do you know anybody like that?' I think I said, 'Wow, not many of those around, but I might know someone.'

So yeah, my buddy Greg basically opened the door for me at Electronic Arts. I don't remember the interview, but I'm sure it was competent or at the very least, I didn't scare them into thinking I was some sort of psychopath or whatever.

Time Extension: Electronic Arts has a very particular kind of reputation today, but back then it seems like it was entirely different as a company. What was the vibe at Electronics Arts at the time that you started working there?

Barnes: Yeah, it was a different company than it is now and it was the largest company I had worked at up until that point.

Britannica Software had probably about 15 or 20 people at the office at most, whereas EA San Mateo had around a thousand people at that specific campus — that was an interesting change. But I was 22 at that time, so I was just super excited and enthused and realizing that this thing that I was doing could be a career and something that I'd be doing for quite some time.

As far as what the place was like, this was 1991, so we had Sega Genesises in the office, and Amigas were still being worked on. I think they were still doing Deluxe Paint IV at that point. So I was personally working on the new hotness — the Sega Genesis — and I was making the kinds of games that I tend to enjoy making: action, arcade-y stuff. So, I was super happy.

Time Extension: One game you worked on that I wanted to mention was Desert Strike. It's quite hard to find any evidence of your involvement with that game looking at the credits. Even looking in the US and the European manuals, it has Michael Lubuguin listed as the sole production assistant. I did, however, find your name in the Japanese manual alongside Michael's. Could you talk to us a little about what your involvement with Desert Strike was and how you became involved with that project?

Barnes: So, when I started at EA, there was a producer and he had several products going at once and really no staff to actually manage them. And so I was mainly doing production work on all that stuff early on, but I was kind of got hosed out of some credits on those earlier games.

The feeling has wained a bit now, but I can still remember the sting when I would get a box and think, 'Yeah! I'm somebody' and then my name wasn't there. In response, I'd occasionally get, 'Oh, it slipped through the cracks, blah, blah, blah'. But it wasn't like today where games could be updated post-release. Back then, it was, generally speaking, one and done. I haven't really looked at all the different SKUs. But it's interesting that you say I'm in the Japanese manual --

Time Extension: Yeah, the Japanese manual has your name in it, but the European and US one doesn't. So it's almost as if the Japanese manual was made later at a later date.

Barnes: Yeah, the Japanese ports generally did come later for us. Generally speaking, anything that came out of Japan would have been after the fact and often very autonomous...

Time Extension: In the second game in the Strike series, Jungle Strike, you would end up receiving a credit as a designer. However, in addition to that, you also ended up being used as the model for one of the co-pilots Scott Antonio. How did that end up happening?

Barnes: In the first three games — the 16-bit ones — everyone in the game was just someone in the office — one of the bad guys was our head of the QA department; the newscaster, she was in HR.

So we basically looked around and plucked people to take pictures of and then ran those through our tool to palletize them. Then we would go over the pixels and turn them into tiles. So when it came time to do co-pilots, again, we just looked at who was there. And John Manley — that's my partner in crime — he said, 'You should be a pilot. You have that look.' And since I was writing all the text for all the co-pilots — I wrote a ton of text in the game in general — I said, 'Yeah, sure, whatever.'

That's why the character's last name is Antonio, because it's my first name. I'm an Antonio, not an Anthony. As for the last name, that was the name of the only other black person I'd encountered in the business up until that time — Scott Tumlin, who was at Antic. So I used his first name. And the call sign Ego was basically just because everyone at the time described me as an egomaniac. I don't think I was an egomaniac. I think I was just confident in my abilities. But I just decided to play into that by being Agent Ego or you know co-pilot Ego who then becomes Agent Ego, who I then kill off in Urban Strike.

Time Extension: So that was your decision to kill Agent Ego off in Urban Strike?

Barnes: We needed to kill someone to show that the bad guy was a bad guy. In films, there's always a scene where the bad guy does something terrible. So there was really nothing better than the cliche or trope of killing one of our own.

But it got kind of muddy in that that whole thing because what happens is the bad guy's son gets into the limo, and Agent Ego is undercover. So he kills us both. He kills off the double agent and the idea is he doesn't care about the collateral damage of his son. I feel in our storytelling, the son part often gets lost, and all that anybody remembers is that I blow myself up in the game.

Time Extension: After the 16-bit games, there were obviously plans for a Director's Cut Trilogy that never ended up happening for the Sega CD. I believe a build of it was even leaked online back in 2017. What can you tell me about that project?

Barnes: The Sega CD had just come out and we were out of position to get anything new done for it. At the time, though, we had been working with this place called Foley High Tech, who had worked on games like B.O.B and Michael Jordan Chaos In The Windy City. And we threw them the heavy lifting of getting the Strike Engine working with Sega CD because obviously it works on the Sega Genesis. But working with the Sega CD proved to be a nightmare. It was quite painful. And I think that Foley High Tech severely underestimated the amount of work it would take to get that thing going.

I think they thought they'd just be able to run Strike and then play Redbook audio underneath and everything would be great. But the way that Strike works is, it is actually constantly streaming from the cart or in the later version streaming from the disc, and it has some fancy tech to do that. So that's why our spaces could be the sizes that they were and have a certain level of detail on such a small cart. It's because it's constantly pulling in these big giant tiles called Mega Tiles. which are made up of a bunch of smaller tiles that make up the Mega Tile.

So our streaming tech on the cart was no problem because the cart's fast. If you yank the cart out or hit the cart, no problem, because everything just goes tits up, so who cares? But the disc, that's different. The seek time and everything on the discs was horrendous.

Anyway, all that aside, Manley and I went and gathered up what footage and we gathered together some documents, and our plan was to do a George Lucas Special Edition and retouch every level. Not to change it too much so that it became unrecognizable or anything, but just to improve a few moments in particular.

In almost every game I've done, there has been a level where I feel, 'Damn it, I wish I had done that better', or 'I wish I had put an extra health pack right there'. There's always moment like that, so the goal was to kind of smooth out a couple of those in Desert Strike, Jungle Strike, and Urban Strike.

There were also some cut levels we wanted to include too. We didn't go back and fully remake them, but there was some cut stuff that we wanted to add back in. Urban Strike, in particular, had a lot of stuff that got cut including a map with a downed 747 where you had to rescue people, and it was just about figuring out how to make that more than just that one little set piece. Cause the ingredients for a Strike level is to have many little set pieces throughout a big place.

Time Extension: You obviously talked about the difficulties of working with the Sega CD. In comparison, what was your experience like working on the N64 while making Nuclear Strike 64 with THQ & Pacific Coast Power & Light?

Barnes: That was an interesting one. God, I cannot remember what I was doing at the time, but John Manley called me and said, 'Hey Traeger's group is doing a port of Nuclear Strike and it needs your help; if you don't help, I think we're going to shoot it.'

Don Traeger was an executive producer at Electronic Arts, and he handled all the basketball games. He got Shaq and Jordan and all of that in-house and really helped build up that business. So he had broken out and done it. He had his own group, and part of that was doing these ports or versions of EA's big action games. And Strike and Road Rash were doing quite a bit of heavy lifting for the action group or EA Games group. So it made sense for him to get those.

So I go and look at what they have, and I wasn't there for Nuclear Strike on the PlayStation — I was off working on Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain and various other things — so I told him, 'I don't like the way it plays. Can I gut it? Can I redo it?' And he said, 'Do what you got to do.' So I did. So Nuclear Strike 64 is not a direct port of Nuclear Strike from the PlayStation. It's actually an almost completely new game.

I took all of the assets, and I took the basic story, and then poured new gameplay into it and made some changes to things. I gave players an actual reticle, so you knew exactly where you were gonna hit. I made the heads up display actually give you information so you didn't have to bounce in and out of the start screen. We did that for various technical reasons on the 16-bit games. But on a 32-bit machine, it just seemed like a pain in the butt to sit there and go, 'Oh, where's that fuel?' Pause. Move a little. Pause again.

The N64 was also not the fastest bus, so when you got to the start screen, there was a noticeable pause as it basically dumped out some stuff and then loaded into memory all of the other stuff for the start menu and map. That bugged the hell out of me and it was just turned out tot be untenable on the N64. So instead we said, 'Here's a top-down that shows you your basics, here's a HUD that says what your loadout is'.

I also redid every level practically from scratch, utilizing the environments, which I felt were really big. In the original, there was a lot of shoe leather there and moving around just for moving around's sake. So I actually took each of the Nuclear levels, chopped them up into two or three levels, and that also helped with the memory because we didn't have to have this giant texture and all this height map data for the terrain or all these objects that were going to be destroyed or moving around.

So all of these changes made it feel more like 2.5D Jungle Strike, rather than a port of Nuclear Strike and updated the cadence to make it a little more immediate for rewards or failure, because you were in the heat of it a little more than in other versions. And then I just tuned it a bit better, because I wasn't a fan of the tuning of Nuclear Strike for the PlayStation. It just seemed out of sync with the times for what players were into at that point.

Time Extension: In recent years, the Strike series has obviously gone on to have this huge influence on indie developers in recent years, inspiring new games like Megacopter Blades of the Goddess and Cleared Hot. How does it feel seeing the legacy of the Strike series today? Is it something you could have anticipated back when you were working on the series in the 90s?

Barnes: No, I mean I was just a guy making games. And I am still just a guy making games. I don't look at any of my of my games and go, 'Yeah, this is this is to change the world. This is going to have legacy, blah, blah, blah.' I just want to make a thing where the people who play it, love it, but the people who don't play it, hear about it. That's generally my goal. So I never thought about it potentially having an influence on other things.

I see a lot of people today who want to make games to leave their mark and approach game development as, 'This is the thing that's going to make my mark and make everyone scream my name long after I'm dead'. I don't really do that. My wife often calls me 'The biggest thing you've never heard of', because I try not do that stuff. I don't spend a lot of time doing interviews. I don't do a lot of talks. My attitude has always been just let me make my games and hopefully enough people like it or love it so I can do it again.

When it comes to Strike, I'm always super happy and humble that people tell me, 'That was my childhood', and that makes me super happy. Outside of paying my bills — that's really why I do it — and if I can influence another game, then that's just a bonus.

When we were working on the Xbox game Buffy the Vampire Slayer at The Collective, I wanted to get a buddy of mine in because he was a huge Buffy fan and he was a combat fan, and we had worked together on Nuclear Strike 64 — it didn't really pan out because the timing was bad. But what was funny is he went to go work on God of War and he apparently showed Buffy to David Jaffe [God of War's director]. From what I've been told, Jaffe stopped and had a team meeting, and he had everybody sit down and play Buffy and said, "Look at this' and then went and retooled the way that their levels and puzzles and pacing and things went. You know, that stuff gives me a warm fuzzy.

And, of course, Buffy wouldn't be Buffy if it wasn't for Capcom's Devil May Cry. So, at first, Buffy was a different game. It was more like Arkham Asylum. It was slower paced, less about direct-input combos and very deliberate in how you moved around. It was almost Tomb Raider-like in a sense of clamouring around and things like that. And then both James Goddard [who was the co-designer on Buffy] and I saw a demo of Devil May Cry at E3 one year, and we just said, 'Holy shit!'

James went back and locked himself in his office for a week and redid all the combat for Buffy and from there, I went and redid how our levels flowed and we worked together on what could kill things and and invented the whole idea about environmental kills. So I mean, we all influence each other in the games industry. I'm just happy to be part of the mix.

Comments 8

What dod Double Helix even DO for Amazon?

There was Ubi game called HellCopter was it a result of the Strike series' success?

@Zeebor15 They rebranded to Amazon Games Orange County and did the online game New World. Tony worked on that a bit, I believe, before going independent.

@JackGYarwood ...Never heard of it.

I went back and forth having a nice text chat with Tony over at the Evercade Discord (one of the few good memories of that hell hole). Nice person, enthusiastic to talk to about games he worked on.

Interesting about Nuclear Strike. I've recently been replaying the series - and I've never played that and wondering which version PS or N64 to play! Maybe I need both now!

His current game appears to be PolyGunR. There's a trailer on his YouTube from GDC last year.

btw, if you guys looking for games that are similar to the strike series I recommend giving a chance to Renegade Ops.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...