Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on February 19th, 2024.

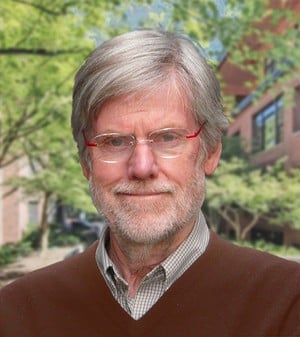

Hal Barwood has had a fascinating career. Not only did he pen the script for Steven Spielberg's first-ever motion picture film The Sugarland Express and the 1981 dark fantasy film Dragonslayer (along with his writing partner Matthew Robbins), but he has also had a fairly lengthy career at the video game company LucasArts where he was behind the creation of the 1992 point-and-click adventure Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis and the 1999 3D action-exploration game Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine.

With MachineGames and Bethesda Softworks set to release their own take on Indiana Jones later this year — in the form of Indiana Jones and the Great Circle for the Xbox Series X|S and Microsoft Windows — we thought it would be a great time to reach out to Barwood to chat about his memories of working on the old Indiana Jones titles. We ended up sitting down and chatting with the designer/writer on a 2-hour-long call, asking a ton of questions about everything from his early inspirations to the obstacles the LucasArts team faced along the way.

Due to its length, we've decided to split the following interview into two halves, with the first part focusing primarily on how Barwood switched from filmmaking to games and the story behind the development of Fate of Atlantis. We hope you enjoy!

Time Extension: Could you talk a bit about your background before getting into games? How did you first become interested in film and filmmaking?

Barwood: I grew up back East in Hanover, New Hampshire on the East Coast of the United States. It’s a college town. Dartmouth College is there. It’s a fancy little town. It feels sort of Metropolitan because it’s got a lot of professors and doctors and a lot of professional, well-educated people. My father ran the movie theatre in Hanover. And he catered to that audience – a well, educated audience. So, you know, spiffy movies, classy movies were what I saw when I was a kid and I got very interested in film even from an early age.

But I was also very interested at the same time in games. Playing games and thinking about them and what would make them better – that hit me early. I also very early came across the idea of paper rock scissors, where you have a psychological contest that goes on and there are unknowns that you can’t figure out. That kind of game is always going to work. So I was very interested in that kind of stuff, but of course, in those days, there was no such thing as a civilian kind of guy like me – an art major in college — who could run a computer.

So flash forward and I was at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island and I was very interested in movies and I had kind of finished my art major at the end of my sophomore year. So I had a couple of years of college ahead of me to try to figure out what to do and I was able to persuade the faculty that they should let me do some independent studies and one of them should be making a little animated movie — I was an art major and I was very interested in animation. They said, ‘Okay’, and they gave me an advisor.

My advisor was the professor of Medieval Art at Brown, and I went to work with him to make what nowadays would be a little Ken Burns-style film and he knew that I wanted to make movies. And he said, ‘You know, I know this guy James Ivory who makes the little movies about Indian miniatures. He actually went to film school out there in California at this strange university called the University of Southern California’. Well, when I found out about that, I wrote an application and I got a fellowship to USC

Time Extension: And that's when you moved to California?

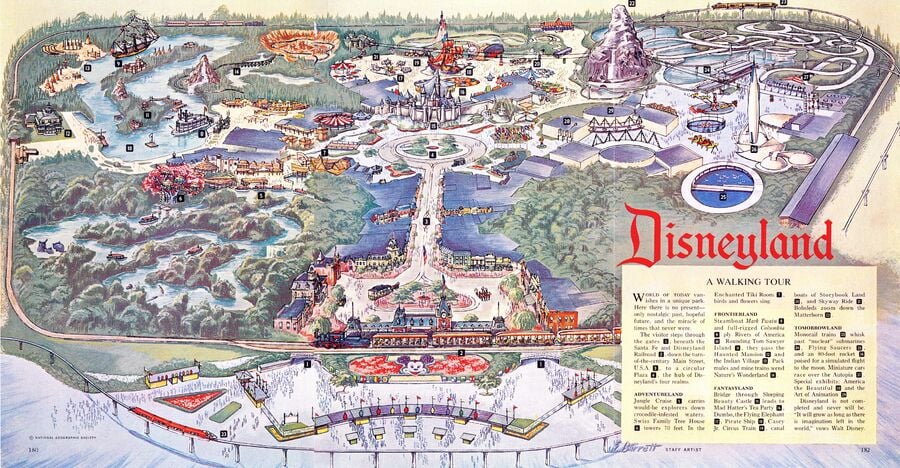

Barwood: Yeah, I had always wanted to go to California from the dour East Coast. Back when I was about 15 years old, we had a subscription to a magazine called National Geographic and National Geographic did a huge story on the finishing and opening of Disneyland. That hit me like a lightning bolt when I was about 15 years old and I thought, ‘I’m going to California where creativity is so well respected that they turn their ideas into concrete.’ I wanted to be part of that kind of life. And so, hey, here’s my chance to go to California.

I married my childhood sweetheart, and we had our honeymoon crossing the country in a car camping on the way and I went to film school. I was kind of there in two stints. In the first stint, I was there with some friends that I made. Then I went off to work for one of my professors in his company for a couple of years, but I was still working on a student movie. I then came back to USC and I got kind of a teaching assistantship there so I had a little stipend and I continued to work on the animated student movie, but my animation teacher suddenly developed a terrible kind of cancer and passed away, so I became the animation teacher. So now I’m there at USC as kind of a teacher but there’s another cohort of students coming through. They included Walter Murch, Robert Dalva, George Lucas, and Matthew Robbins. And they became my movie friends until the present day.

So I was very interested in film. But Matthew and I, when we started talking, we just couldn’t stop, and we both realized we both wanted to be writers. So we became screenwriters. We wrote about 7 screenplays before number 8 The Sugarland Express finally got made and we finally found out what it was like to see one of your projects have the light of the fair. But eventually, we wanted to make our own movies, and one of those movies, of course, was Dragonslayer.

Time Extension: Why did you decide to switch from movies to video games?

Barwood: In the middle of Dragonslayer, we were working very hard at a location near Pinewood outside London called Stockers Farm. We were busy rehearsing, we had an Iron Age village set up with thatch roofs and gasoline ready to burn them up, and as we were busy getting all of this together, I realized I would probably be happier instead of watching all of this stuff go on – which was probably the most exciting day of my movie life – sitting in an old trailer all by myself programming an HP41c calculator to play Hunt the Wumpus – a Dragonslayer version.

I realized if that was true and I like to do coding more than I liked making a movie then I was in the wrong business. And it took me 10 years and a detour where I directed a movie of my own in the middle of this all called Warning Sign before eventually, I did succeed in becoming a pro at Lucasfilm Games.

Time Extension: When you first joined Lucasfilm Games, it had just released Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure, which was designed by Ron Gilbert, Noah Falstein, and David Fox. How did you get involved in working on the next Indiana Jones title?

Barwood: The reason I was hired at Lucasfilm Games was because [the last game] exhausted the guys behind The Last Crusade — who all wanted to go on and do other projects. So, Lucasfilm knew that the company wanted to do another Jones game to follow up the hit, but they didn’t want to do it.

So they looked around and I had been hanging around. I was a friend of George and he knew of my interest in games – so did Steve Arnold, who was running Lucasfilm Games at the time. So I became kind of friendly with them and then eventually the opportunity popped up and I said, ‘Okay’.

I was willing to abandon my movie career because I was very interested in doing games but also because after Warning Sign I realized, ‘Gee, you know, here I am, I’m 40 years old and I’m making this movie. I know what I’m doing, but it isn’t a movie that is going to open up a lot of opportunities for me to be continuously busy directing movies.’

So I thought, ‘You know, if everything works out and I do a few scripts and so on, I might get 4 or 5 more movies in my entire career.’ And I wanted to be productive. So I just thought that’s another reason to go and do games, because I’m pretty sure I can do more of them, and I did.

Time Extension: Is it true the project started out being based on a script about the Monkey King?

Barwood: Yeah, so what happened is that they had a rejected script by Christopher Columbus for another Indiana Jones movie and they thought it was good enough for a game.

Noah was kind of my mentor on this project a little bit, and we realized that it was a terrible script for a video game. It was obscure it was all going to take place in Africa where there was a Chinese influence and it was going to be about something called The Monkey King. We just couldn’t figure out how that was going to be very interesting.

Chris Columbus is a wonderful writer & director and I don’t want to sneer at his work, but it just was an inferior script. So I kind of thought about stuff, and at that time, we were located on Nicasio, California at Skywalker Ranch in one of the buildings there and George had developed a library. The library was designed for production design, so it was full of gigantic, illustrated coffee table books for people to use as visual reference for something they may want to do in a movie — costumes, locations, styles.

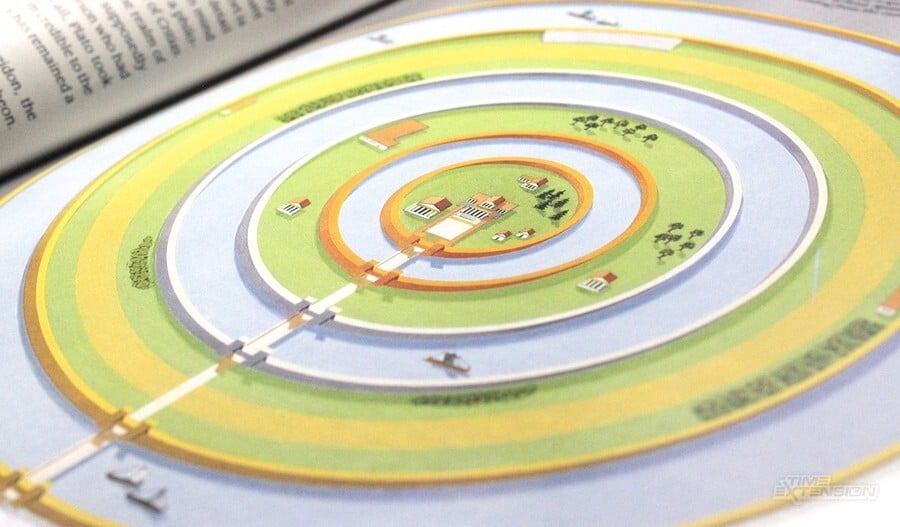

So Noah and I went into the library to see if we could go looking for something and we found this book called Mystic Places. And when we saw the diagram of Atlantis in the book, we thought, ‘Oh my god, that’s a game!’ All we had to do was see the way it was laid out with the concentric circles interrupted by canal and we just thought, ‘We can make this into a game.’

Time Extension: How did you develop the story from that initial concept?

Barwood: Well, you know, I’m a story guy and so after we figured out this was a game, now we had to construct a narrative (which I did) and I realized that we needed a way to pull ourselves through the game and that was the creation of the character Sophia Hapgood who had by chance been at a dig site where she recovered a medallion that had mysterious powers dating from Atlantis – one of the gods of Atlantis Nur Ab-Sal.

So I invented this kind of shifty character who Indy gets together with and they try to find Atlantis and try to figure it out. We were able to take advantage of the fact that Plato actually talked about Atlantis in his Dialogues or a couple of them actually – he briefly mentioned it. So we assumed that there was a lost Dialogue, which you could recover and that could help you get to Atlantis. So that became a quest object in the story. It was fun to get this all set up.

Now another thing that was going on was at the same time I was trying to get this going Noah had sort of gone off to do other stuff and I had also been playing through Monkey Island. And I thought Monkey Island — which is an absolutely wonderful game and one of my favourites among adventure games — like a lot of adventure games [before it] eventually became kind of starved for visual novelty. So, I constructed the story of Atlantis in a series of bubbles where you would go from one location to another to try to sustain and replenish the visual impact for the player.

So that was sort of a new sort of thing to do. And lucky me, SCUMM was being advanced and we could now have scenes where characters could be scaled in effect in perspective in the locations, which was very nice to have. It was a jump past the more primitive stuff that was going on. And some of the visual interface stuff had been improved so we were pretty excited about that. And we had a new sound system called iMuse.

Time Extension: One of the more iconic moments we have to talk about from Fate of Atlantis is the famous opening, which is a credits scene where players need to interact with their environment to progress through it. I’m wondering how did that come about?

Barwood: It was my idea. I thought we ought to immerse people in media res. Everything should be going from the moment it starts. I didn’t want to do a credit sequence where you had to have people sit through it. So I decided what we would do is we would just have Indy and you are left to figure out on your own how to move him but what would happen is you would eventually fall into a trap.

So you didn’t really have to understand what was going on for the whole thing to progress because without much work you would just suddenly fall through the floor and you’d be in the next sequence, and there would be another credit, and you’d do it again and again until the game actually started. You’d get an education without us having to say it was an education on how to run the game.

In those days, we did do a thing called "Pizza Orgies" where an unfinished game would be presented to other people in the company while working on your project and they’d all sit down and try it out. And that whole sequence went over well.

Another sequence later where you first met Sophia did not go over well and we had major revisions after that. So that was a great proving ground that it would work. And I have to say it’s a great contrast to something like the early Tomb Raider games where you have to go through and kind of take a lesson in how you’re going to run her. You don’t want to do that. For me, that’s a stopper. I’ve got to go to school? I’d rather go play another game.

Time Extension: The game memorably had three paths (Wits, Fists, and Team), which all progressed slightly differently. How much of a production headache was it to wrangle those three paths?

Barwood: Anyone who knows anything about software knows that it was an enormous headache. Oh my god! This was my first game at Lucasfilm Games and I was a little bit naïve. I’d done lots of game coding and stuff and my own individual games before I got to Lucas, so I knew a lot of stuff. But there was a mantra that Noah was quite fond of saying, which was, ‘You don’t build things that people aren’t going to see.’ And yet, he’s the one who suggested, ‘You’ve got to do three paths.’

What had happened is that they had gotten a lot of [conflicting] feedback from Last Crusade where they introduced in an adventure game a kind of Tekken fighting system. So Noah thought ‘We’ll do three paths and we’ll have one path where you fight a lot, another path where you’re mostly going to do cooperative puzzling (where you use Sophia to advance), and then we’ll have another path where you just basically do traditional adventure game puzzles.’ I thought, ‘Sure! That’s a great idea.’ But then Noah went off with his other stuff working on a thing called The Dig and I got stuck doing those three paths.

Well, the only way we could get them done was to interweave some of the elements into each of the paths, but in different orders and with different emphases. So we did that and I was able to get it done but it was the hardest thing in the world to get that done. And that’s when I realized we were never going to finish the game if we kept the three paths once we got to Atlantis. Once you’re in Atlantis, that’s it. Which is a huge thing to be able to do and we did get the game done in time and so forth. But the three paths were really interesting and we did have players who went down each of the paths.

The team path is my favourite, but I was also interested in doing other things. At the time, there was a sensibility at Lucasfilm Games, that was sort of led by Ron and to some degree David Grossman, that things should be funny. The idea was that they were doing comedy games. Well, I’m more interested in melodrama. So it was a good choice for me to do a Jones game because I appreciated the adventurous quality of the Jones character and the kind of milieu that they kind of set him in.

So I thought, 'Listen, this is an adventure game, but we should realize that Jones is never far from being killed in his movies, and making a terrible mistake and the game should allow you to get recycled into the game again from a death scene.' They agreed, and then I also thought we ought to have what at least seem like action elements. So I invented camel racing. I taught SCUMM how to do tile graphics. We did the balloon ride stuff and we did the car chases in the city. It was fun to do all those things and give the game a sense of dimension that previous adventure games at Lucasfilm Games had never had.

Time Extension: When I spoke to Peter McConnell a couple of years back, he mentioned you were one of the main supporters of iMuse within the company. Do you remember being particularly outspoken about the benefits of the sound system?

Barwood: Yeah, Peter and Michael spent a year or so at least trying to get iMuse running. It was a big project for them and it was kind of a serious thing to happen at Lucasfilm Games where we thought we were inventing something that would be a useful tool for other people and so on, and worth doing. And it was! I thought it was terrific, but the reason I was interested in it was, of course, because games are different than film. You don’t have the same kind of sense of pace that you have in a movie.

In a movie, there is no interactivity in the kind of way you have in a video game. So you can run a soundtrack and it just works. But in a game, especially in an adventure game, where you have to pause to think things over when you’re trying to solve some puzzle somewhere, [it doesn't work as well].

At some point, we found out that the more elaborate uses of i-Muse - at least in our game - just produced a kind of confusion. It just seemed overly-decorated and it wasn’t terribly successful. But the one thing we did that really worked like magic happened when eventually the three paths that we created to take advantage of people’s tastes in how they play games collapsed into one as they arrived at the diagram that I showed you.

Indy is a tiny ant running around and the Nazis are little ants also running around and there’s kind of subtle, suspenseful music that is going on. And what’s interesting is when your little ant stops to think things over, the drum track fades out, but when you start to walk again the drum track comes back to give you a sense of urgency. That just worked great. It was very simple. All we did was if Indy was moving, we ran the drum track. If Indy was not moving, we didn't. That was iMuse at its best. It was so simple and very effective.

Time Extension: In 1991, ahead of the game's release, Dark Horse Comics released a four-issue comic adaptation of Fate of Atlantis. What was your involvement with those?

Hal Barwood: I wrote them. I did the first four. But it was a very strange experience. I live in Portland, Oregon, and Dark Horse lives in the next town down the line – a place called Milwaukie. They’re still there. It’s wonderful. They’ve had a lot of success and they could tap into a lot of really good artists to do their stuff. I’m not entirely excited about those comic books though and the reason is that the artist who got in there thought they knew a lot more about writing than I did and they were wrong.

Time Extension: Interestingly the comic features a couple of the cut locations that were going to be in the game but were cut for time like Cadiz and Leningrad. Do you remember anything about those cut locations?

Barwood: I just remember there’s always time pressure. You’re burning money every month as you work on a video game. When you’re shooting a movie – let’s say it runs two hours and movies go through at about a mile an hour — it’s about 10,000 feet of film in a feature film but you probably have to shoot 250,000 feet of film while making that film. So that’s kind of the analogue in video games. You get stuff going and you hope that if you get it all done, you can have a game. But you also hope that you can cut things too and you’d still have a game, so you overplan.

So we did start to do the Leningrad sequence and we did start Cadiz and so forth. But the truth is they weren’t coming together. And as the other material became available to look at and play, we realized that, ‘Hey, we don’t need it.’ So we dropped it. Now when all of the materials are globbed together to become the resources for this game, I guess some of that stuff got stuck in there and got out.

Time Extension: At the end of Fate of Atlantis, there was a tease for another Indiana Jones title featuring Young Indiana Jones. From what I’ve read, this was a reference to a cancelled Young Indiana Jones game that Brian Moriarty was working on – an educational title. Do you remember anything about that?

Barwood: You know I don’t remember there ever being a serious effort to do a Young Indiana Jones. I certainly didn’t.

I have to say, though I love the Jones character, and I’m very interested in that franchise that George and Steve developed. It’s different from Star Wars. In Star Wars, everything takes place in a science-fiction fantasy world – a very convincing one and a wonderful one – but the stories all have to revolve around the political problems of the Empire and so on. Jones, meanwhile, is kind of a fantasy character but he’s embedded in a version of the real world. And the interesting thing about it is that you’re really interested in Jones as a character and there’s a series of stories — any of which could follow any other one.

The stories are individualized and I like that very much because I’m a story guy. I want to be able to write stories that don’t involve the same thing again and again. So I’m very attracted to Jones and I like the character very much. He’s a wonderful movie hero and works really well in a game as well. So I was very interested in that.

Time Extension: I also have to ask you about the cancelled follow-up Iron Phoenix, which was one of a number of unrealized Indiana Jones projects being planned between Fate of Atlantis and Infernal Machine. Do you know anything about that project?

Barwood: I know very little about it. They were trying to get it going. We did publish other Jones games, but nobody at Lucasfilm Games ever did them. They were done externally with guidance and consultation from people at LucasArts.

So the Spear of Destiny and Iron Phoenix, which I don’t think ever got made – those games I just know very little about them. The only one I worked on at all was stalled out and I can tell you about that one. It was basically a game that they were going to do internally and the idea was it was kind of like The Boys from Brazil or one of those stories where the Nazis after the war took refuge in South America.

In our case, we decided that we were going to try to resurrect Hitler himself and it was a really interesting idea. It was as if he was part of the supernatural quality of the Jones universe. Jones starts out everything looks kind of normal and real, and then eventually fantasy elements come in. At the end of Raiders, ghosts are coming out of the Ark, and so on. I thought that would be pretty clever. Then we realized our adventure games did well in the United States, but they also did very very well in Germany. Well, if we did a game that involved Hitler, you’re not going to sell one unit in Germany. So that game was cancelled. Probably wisely.

Time Extension: Nazi zombies is a thing that’s been done a lot in film strangely.

Barwood: It is. I think as the Jones’ universe became formulaic to the people who were involved with it in film especially, but also in games, they just thought that Nazis were an inherent part of that world. I didn’t think so at all. I just think it was a tremendous mistake to have Nazis in Dial of Destiny and I just thought that resurrecting and rehashing that material was not a good idea.

Time Extension: And of course, one of the big things about Infernal Machine is it does take things forward and it does go beyond Nazis, introducing a Soviet threat. But then Emperor’s Tomb & Staff of Kings go back again.

Barwood: They went back. They just couldn’t think of something that didn’t involve the Nazis and the franchise was lying heavy on their shoulders. And so, they just thought they should go and do what had already been done. That’s a creative lapse, which I’m sorry to have been aware of. I wish it hadn’t happened...