Compared to the relatively conservative video game hardware market of the modern era, the '90s seems like a wasteland of failed systems and also-rans. The 3DO, Atari Jaguar, Commodore CD32, NEC PC-FX and Sega 32X were all pieces of hardware which, at launch, found themselves positioned as the next big thing in interactive entertainment, yet all failed to live up to their promise and consequently endured short lifespans thanks to consumer apathy.

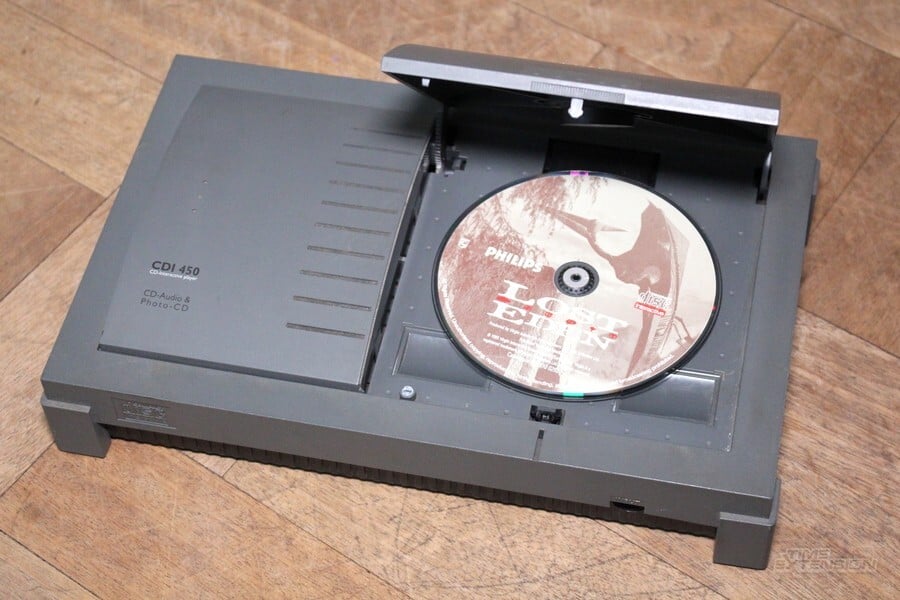

You can add to that rather pitiful list the Philips CD-i, but what makes this particular machine so fascinating is its long history and – of course – the fact that it is one of the few non-Nintendo platforms in the history of the games industry to play host to officially licenced Nintendo games – but more on those shortly.

Despite launching in 1991, the CD-i's origins actually stretch back to the mid-'80s. The compact disc – a digital storage medium created jointly by Dutch firm Philips and Sony – had made sizeable impact in the world of music, and was beginning to make itself known in the realm of computing; its ability to hold large amounts of data (as well as high-quality music and video) made it attractive to developers, and it was becoming increasingly obvious that as soon as the cost price of CD drives dropped, the format would take over from the likes of expensive cartridges, slow-loading cassette tapes and volatile, low-capacity floppy discs.

With this in mind, Philips and Sony decided to work together to lay down the foundations for a new CD standard which would leverage the format's potential for multimedia functionality. Work on this 'Green Book' spec began in 1986 and was finalised at the close of 1988. By this point, NEC had already released a CD-ROM drive for its popular PC Engine console and gaming giant Sega was also investigating the potential of the compact disc; however, the fact that Philips and Sony convinced Japanese veteran Matsushita – then the world's largest electronics company – to join its new 'interactive CD' alliance spoke volumes; Matsushita would later exit this trio but there remained a real sense of optimism about the format.

For Philips, there was a hope that CD-i (as the format would come to be known) would create a nexus for the worlds of music, movies, games, education and digital entertainment. Instead of buying a CD player, VHS player or games console, consumers would simply invest in a single machine that could cover all three bases. Curiously though, the company decided to avoid mentioning the potential for gaming in its early promotional material, instead aping Commodore's messaging around its ill-fated CDTV system and pushing the more worthy elements of its feature set, such as interactive CD albums and encyclopedias. The first version of the console – the boxy 205 – looked exactly like a CD player, and only had one joystick port. The controller that came with it was totally unsuitable for gaming, although over time hardware revisions would attempt to fix this oversight, as well as add a second controller port for two-player software.

Upon its launch in 1991, the CD-i was met with a muted response, something the company later acknowledged was down to poor marketing and the fact that it generally ignored games as a means of getting the system into homes. Another major issue for Philips was the fact that by 1991, the CD-ROM war was really beginning to build up steam; Sega's Mega CD arrived at the end of the year in Japan and systems like the 3DO would soon start gobbling up column inches worldwide. Meanwhile, the CD-i's 'Green Book' spec was drastically inferior to what true 'next gen' CD-based consoles were about to offer. For example, data streamed from a CD was limited to 170K/sec, around half what the 3DO would later manage. Philips had been bested by the fast-moving nature of home technology – and there arguably hasn't been a period in gaming history where tech moved as fast as it did in the early '90s.

Despite a lacklustre start and the arrival of more powerful systems on the market, Philips persevered. A revised model – the 400 – clad the hardware in more console-like clothing, and the system finally got a proper joypad. The release of the Digital Video Cart – which included an MPEG-1 chipset and allowed CD-i users to play Video CDs as well as enjoy high-quality FMV in certain games – gave the machine a real selling point; lest we forget, this was a time before DVDs had arrived and while Video CD movies suffered from compression problems, they represented a definite step up from VHS. The cart not only turned the CD-i into a valid replacement for your ageing VHS player, but also added 1.5MB of RAM which could be utilised by developers to create better games.

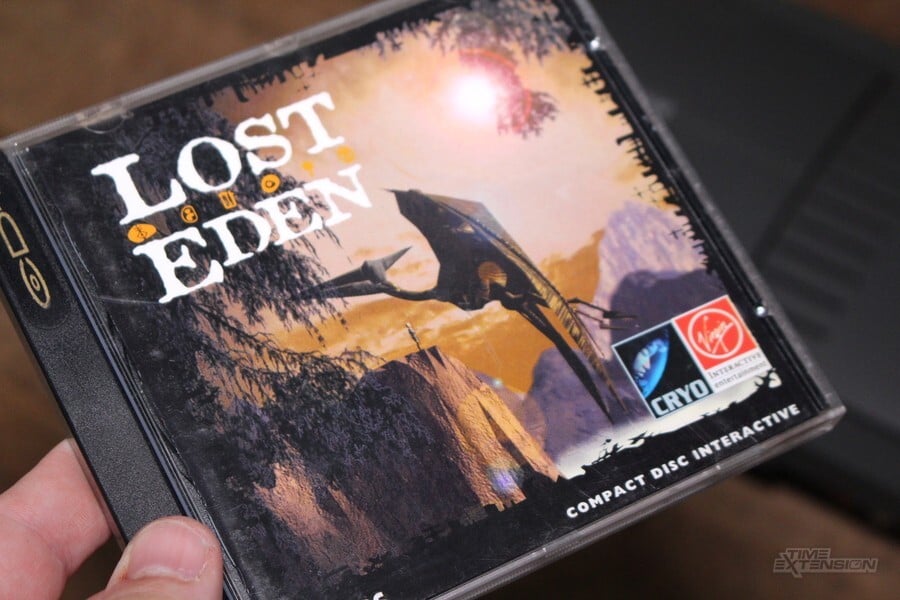

Slowly but surely, Philips awoke to the potential of gaming on its platform, and the standard of software rose. Titles like Burn:Cycle, Chaos Control, The Apprentice, Lost Eden, The 7th Guest, Creature Shock, Flashback and Kether proved that with the right amount of effort, CD-i was capable of hosting semi-respectable titles. However, it is the handful of Nintendo games available for the platform which are perhaps the most well known – if not for all the right reasons.

Before we dig into these releases, it's worth looking at exactly how the likes of Mario and Link ended up on the CD-i. Sony's work with Philips on the format in the '80s wasn't just for the good of humanity; like its Dutch partner, it too wanted to capitalize on the explosion of interest in interactive entertainment and established a publishing arm – Sony Imagesoft – to this end. Sony was, by all accounts, jealous of the kind of domination that Nintendo had achieved in the Japanese games market, and hardware like the groundbreaking Game Boy caused such consternation in the halls of Sony HQ that it was reported that one engineer resigned from his post in shame, with the general feeling being that Sony should have used its burgeoning Walkman range to launch a similar device, but had been beaten to the punch.

Despite this growing animosity, Sony was wise enough to know that it couldn't force its way into the games market and saw the obvious potential in becoming a hardware partner with Nintendo, the world's biggest gaming brand. It designed and manufactured the SPC700 chip at the heart of the Super Nintendo's S-SMP audio processing unit, lending the 16-bit system with the kind of music that even CD-based systems struggling to better. Around the same time that the Super Nintendo was in its development phase, Sony signed another agreement with Nintendo to create a CD-ROM drive for the console, using the CD-ROM/XA standard that had been authored by Sony and Philips.

For Sony, this deal represented a way into the games industry – in addition to creating a bolt-on drive for the SNES, it would also create a stand-alone console known as the PlayStation. As part of the proposed deal, it would also retain licencing rights to the 'Super Disc' format that both variants of the hardware would use; effectively, Sony would make money off software released for Nintendo's system. The rest is, of course, well-documented history; Nintendo rightly deduced that Sony was simply using the agreement to satisfy its ambition to gain a meaningful foothold in the games arena, and in 1991 it publicly broke off the engagement at the Consumer Electronics Show, announcing that it had penned a new deal with Philips to create CD hardware for Nintendo's home console - the day after Sony had revealed its plans for the SNES CD-ROM.

The hardware never happened, and the SNES PlayStation became the stuff of legend – until very recently, when a working prototype surfaced which made it clear just how far development had progressed before it was shelved. Sony would lick its wounds and create a new PlayStation system, but Nintendo would ultimately pull the plug on the CD-ROM hardware for the SNES – ironically because it felt the CD revolution, as spearheaded by the likes of the CD-i – had failed to make an impact. Still, it was now indebted to Philips, and as a means of extracting itself from the proposed deal, it allowed the Dutch firm to use some of its most recognisable properties to bolster the CD-i's pitiful games library.

The end result was a selection of games which don't do the source material justice; Hotel Mario hardly ranks as one of the plumber's best outings and although both Link: The Faces of Evil and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon have an interesting place in gaming history, they're generally regarded as poor takes on the famous Legend of Zelda franchise. Zelda's Adventure is even more of a disaster, while Mario's Wacky Worlds never got as far as store shelves. While the deal resulted in some modest software sales for Philips, these games did little to endear the CD-i to Nintendo's audience and certainly didn't convince the masses that the platform was the future of gaming. Philips continued to pour money into promoting the platform but it was ultimately for nought; even the introduction of basic internet connectivity via the CD-Online service wasn't enough to give the CD-i a stay of execution.

Philips eventually abandoned the system in 1996, with around 570,000 units sold globally. It is believed that the project cost the company around a billion dollars, a reminder of just how high the stakes were in the games industry at the time. While the CD-i is utterly fascinating from a historical viewpoint, it's a difficult machine to recommend today, even if you're a seasoned lover of retro. So many of its key games are FMV releases lacking in engaging gameplay; relics from a time when developers seriously believed that gamers would be satisfied with basic interaction as long as live actors and CGI sequences were included. Another rock block for potential collectors today is the fact that the lithium battery which powers the CD-i's 8k of non-volatile memory dies over time, and many systems won't even boot up properly unless a drastic and invasive modification is undertaken. This fact – combined with a lack of decent software and the surprisingly high value of machines on the secondary market – makes CD-i one to avoid, unless you're hell-bent on collecting every piece of gaming hardware ever.

Philips abortive attempt to crack the games market seems destined to be little more than a footnote; a well-intentioned move to unify the music, movie and gaming mediums in one place, but one that was almost doomed from the start. But hey, at least it has Mario and Zelda, right? Right?

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Mon 23rd July, 2018.

Comments 38

Asking where the ‘CD-i’ Section was at a local store must have been pretty embarrassing

I saw one in a charity shop with Zelda about 15 years ago for nothing! Probably should have picked that one up if only for the curiosity factor... still, I just knew it was junk from looking at it at the time.

Still have this under my bed in storage with 7th Guest, Zelda wand of gamelon, micro machines, burn cycle, chaos control, lost eden, Hotel Mario, Little Divil, some edutainment crap and Voyeur. Beside games also have Pink Floyd Dark side of the moon album and oddly Four Weddings and a Funeral.

It was certainly quite appealing in my youth to see those FMV games, as was mainly use to SNES and Megadrive at the time.

Edit: Lemmings and The Apprentice I believe are in there too. Edutainment was some bears painting and mathes thing, a planetary golf game, and Flintstones X Jetsons time warp. Oh also Ms Pacman.

CDi....ohhhh Boi......

This thing couldn't sell itself at a flea market. I'm convinced without this Philips-Magnavox would still actually exist in a meaningful way.

Ah yes, the CDI, probably the worst game console ever made. It is right down there with the Virtual Boy, a console that just never really succeeded at anything. It also had some of the worst controllers ever made.

@Matthew010 "Nice of the Princess to invite us over for a picnic eh Luigi?"

@Majora101 The CDi pretty much exists only as a meme console these days... it found some relevance on youtube with people laughing at how awful it is.

The CDi is one of the very few European 'game consoles' and it had a modest fanbase here. If Philips didn't push the whole FMV multimedia thing onto it, and made it more competent at playing games, they may have rivaled their own past buddies, Sony. Those Nintendo licensed games totally were a disaster, and no self respecting Nintendo fan in the 90s would have touched them. That probably did the CDi a lot of damage.

This is possibly the only console I can think of that I have never had any desire to own - not at the time and not now as a sucker for all things slightly unusual in the world of retro gaming.

@Aozz101x “I hope she made lotsa spaghetti!”

I really want one of these, if not to make fun of it with my siblings. Making memes and jokes about Hotel Mario and Link: The Faces of Evil is very commonplace between my friends and I, so being able to experience the “magic” of one of these cherished classics would be hilarious.

@Aozz101x "You know what they say, all toasters toast toast!"

Also, this page is beautiful! https://www.torwuf.com/a/fe6o52wsfyvuhnwbxmnskyw4oq

@JayJ Virtual Boy DID succeed at one thing - Wario Land. CD-i didn't really succeed at ANYTHING.

Used to play this system a lot at my Uncle's when I was a kid. I remember playing games like Dragon's Lair 2, Space Ace, some Pinball game, a monster themed shooter puzzle game and 7th Guest.

He also had Wand of Ghamelon... it was bad... really bad. I thought it was pretty novel as a kid though, because it was the first time you ever got to play as Zelda in a game.

I remember seeing these on TV back in the day, and really wanting one. Little did I knew there were hardly any games to play in them.

And it was systems like this that made so many gamers who grew up in the '80s-'90s hate the idea of any videogame that was even close to being an "interactive movie" (typical CD-ROM affair of the time), which is why to this day it's still hard for some people to get behind games that advertise how great their story and character arcs are above basically everything that actually defines them as an interactive videogame vs any other kind of non-interactive entertainment media. I'm one such gamer.

@SethNintendo Well, I guess if we added up all the times that we should have picked something up we'd have a fortune!

In reality I expect I would have sold it a few years later when it was collecting dust... I'm currently debating AGAIN as to whether I should get rid of my Dreamcast, GameCube, N64 etc. But when you think about it a few beers later and you've got no Shenmue 2 and a hangover instead haha!

This console’s only merit is the sheer amount of memes generated by it.

CD-i gaves us two of the most iconic Zelda games of all time!

@Damo Good read and just the sort of article NL needs to remain relevant and compete with the You Tube channels.

I've never seen or played a cd-i.

Thanks for this article!

@XenoShaun You mentioned The 7th Guest and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon in the same sentence! I’m such a nerd I got giddy.

@mid_55 Yeah, I would only consider ever buying one if it could be paid for by chump change. A historical curiosity, sure, but not a must-own.

Enjoyed my cdi. Used it a lot for watching movies and tv shows. Still remember some 7th guest puzzles to this day.

@Matthew010 All toasters, toast toast lol

The scary part is that this thing was on the market longer than the Dreamcast but had none of the fun that the Dreamcast offered.

Growing up in the 90's I had a Snes, and I also had a CD-I

I've got to be honest, there was a lot I enjoyed about it.

Burn Cycle was an ace game, and stand by it was ahead of what else was happening at the time.

It was also ace to be watch a film on a cd, which I admit was a novelty.

Had loads, Top Gun, Naked Gun, Spitting Image you name it.

Even had Queens Greatest hits, which was lo res music videos of Queen.

It also had quite a few good pieces of software, where you could paint etc.

Far from a great machine, but I've got fond memories of Philips CD-I

I'll have to crack it out again soon.

When are getting em cdi zelda games remakes bois

@Damo - thank you for that article, much appreciated. I do enjoy it when the site spreads its wings a bit.

As an older gamer I like the nostalgia - or history lesson depending on age of reader.

There was a time when interactive FMV like Dragon's Lair were incredibly exciting and felt like the future.

And now, games and expectations have changed so much that we take the Skyrims, LA Noires and Breath of the Wilds for granted. (And winge about FPS.)

I feel lucky to have lived through so many step changes, from the ZX Spectrum and Manic Miner through to Knightlore, to Mortal Kombat on Amiga, Tomb Raider, Gran Tourisimo and Metal Gear Solid on PS1. Genuinely exciting times.

I don't know if we will see such advances again, if there is anything new out there. But for all that nostalgia, now is the best time to be a gamer, now .

Did I seriously just watch that entire thing... the entire Zelda cd-i

The Commodore CD32 aka the Amiga CD32, as it was actually called...

As for the Philips CD-i: that thing was only ever destined to be a complete joke and a failure. Typical Philips: coming up with a rather good idea on paper, then screwing it up in real life, and then letting other companies come up with MASSIVE improvements that actually DO make their devices successful...

I have played a couple of titles on the CD-i, and I found all of them forgettable. And those licensed Nintendo games were of course utterly atrocious, and it is sad that they even happened in the first place.

I feel like, at this point, most people online know about this beast. AVGN did some excellent videos on it years ago, and since then most gaming YouTubers worth their salt have mentioned it in passing. This is a neat read, but I bet not much new that most of us haven't heard before.

Still, I would be interested in most content like this NintendoLife always does a good job of presenting it in a nice clean format that is easy to access.

Mad Dog Mcree.

One gaming system I never had. Don’t even recall seeing it in any stores!! 3DO however, I did take the expensive plunge...

I wonder what Ganons up to?!

I still want to play Burn Cycle.

I had a CD-I...3DO...and the Jaguar. The systems weren't really that bad...well...the CDI was in games...but it was my first CD video system. It was pretty amazing at the time watching videos from CD. Also, I thought the Jaguar was pretty good. It wasn't any Sega/Sony/Nintendo system...but it had its moments. I also had and loved the Turbografx with CD attachment. To this day Ys 1&2 on Turbo CD is one of my favorites games ever.

@Mii_duck Manic Miner! Nice... and Horace goes Skiing perhaps?

Chucky the Egg? (if I remember correctly!)

The side-scrolling Zelda games were remade not long ago, with improved framerate, smoother controls, better jumping mechanics, but the same excellent graphics, music, and level layout. The author released them for free on PC. A quick Google should yield results.

I'm not kidding - they really are fun games. The speedrun community was having a blast going through them.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...