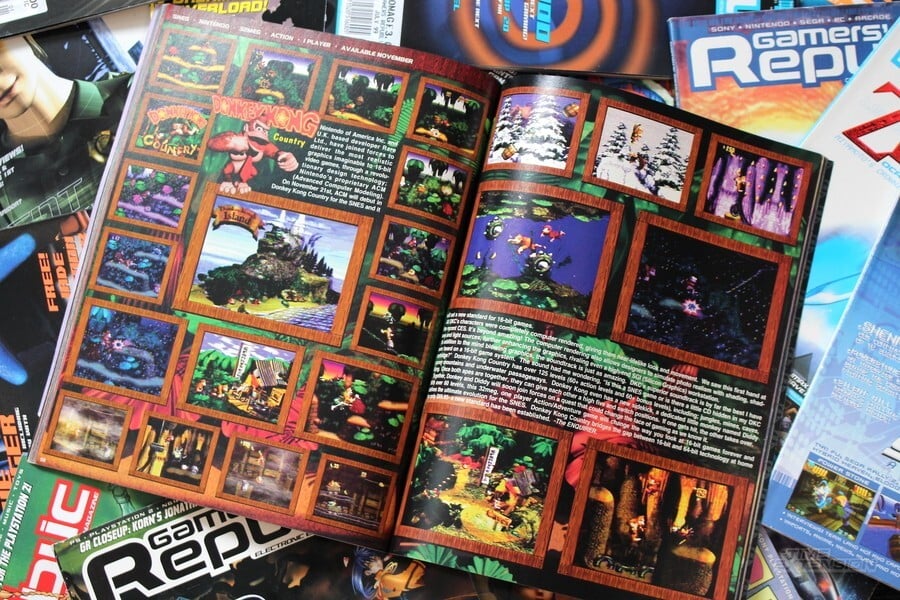

If you were a North American gamer who was active during the early '90s, then chances are, you've heard of GameFan magazine. The anarchic alternative to the likes of GamePro and EGM, it began life as a catalogue for a mail-order video game store before evolving into a monthly publication which became notable for its unique art style (including bespoke art by Terry Wolfinger), excellent screenshots, strong focus on Japanese gaming and obsession with anime, the latter of which was just breaking through in North America.

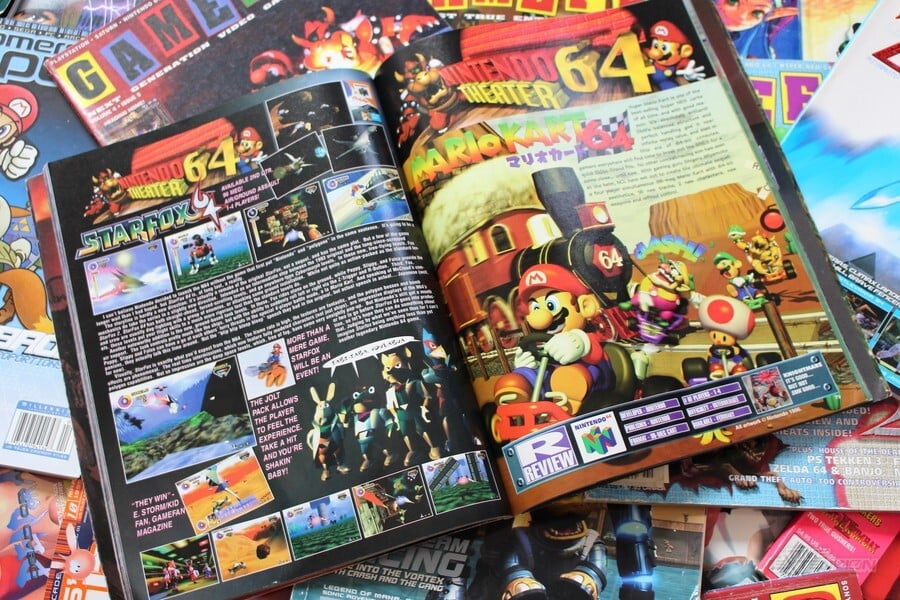

While it began its life during the 16-bit era, GameFan would preside over the launch of the PlayStation, Saturn and N64, charting one of the most significant and exciting periods the games industry has ever witnessed. Titles like Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Super Mario 64, Star Fox 64, GoldenEye 007 and Pilotwings 64 were all covered in incredible depth, often receiving multi-page features packed with information, art and screenshots across successive issues.

GameFan has its fair share of eye-opening stories, involving racist comments, alleged drug-taking and pirated Capcom games – all of which you're about to hear about from the people who lived through them. It eventually died in December 2000, but was replaced – in spiritual terms, at least – by Gamers' Republic, a rival publication headed-up by GameFan co-founder Dave Halverson, an individual who has become something of an infamous figure in the realm of games journalism. With a more polished design style, Gamers' Republic carried on much of the good work seen in GameFan, and would cover the arrival of the Dreamcast, PS2, GameCube and Xbox consoles. That too would eventually fold, with Halverson establishing Play magazine in its wake. In 2010, he would attempt to resurrect GameFan, with little success.

We sat down to speak with several former staffers to document the story of these incredible magazines. Buckle up, because you're in for quite a ride.

Could you give us a brief history of Diehard GameFan?

Mollie L Patterson: The finer details of how DieHard GameFan came to be, in terms of the exact people involved, are a bit complex. However, the magazine spun out of DieHard Gamer’s Club, a retail and mail-order store that tended to focus on Japanese imports. A few issues of a small catalogue for the store were produced, and then that transitioned into becoming a full-fledged magazine in late 1992.

For the first two issues of GameFan, a bulk of the copies were given to shops local to Southern California (particularly the Los Angeles area) to sell, or perhaps distributed in other ways as well. It wasn’t until issue #3 that the magazine was able to secure a national distributor, which is when I found out about it. I happened upon an issue at a local Software Etc/Babbage's (can’t remember which) store, thought it looked interesting, and then picked it up.

What was it like to work there?

Mollie L Patterson: Shocking, at least at first. I came from a history of making video game and otherwise-focused fanzines starting in junior high, and back at that point in time, even producing a publication on such a small level still took a lot of technology and know-how (outside of doing the older-school “cut and paste” style of zine). So, my expectations for what GameFan would be like were very high, since we were talking about a full-colour, professional-printed, nationally-distributed magazine.

My first day in the offices, I was dumbfounded at how “garage” the whole organization felt. There was no consistency to the types of computers being used (outside of mostly being Macs), and many of them were more out of date that I’d expected. The space that was being rented in an office building in Agoura Hills, CA, was a total mess, feeling more like a college fraternity than a professional company. I really couldn’t believe how that group of people could make a full and proper magazine every month under the circumstances.

Once the shock wore off and I got into the swing of things, there were definitely bad parts, but there was far more good. It was like a dream come true. This was long before the age of the internet as we know it now, before there were all of these huge video game-focused websites, podcasts, YouTube channels, streams, or the opportunity for anyone and everyone to get their voices out there. Getting hired on at a gaming magazine was still a huge position, and meant my writing would have a reach that few others out there could claim. And, GameFan was the perfect fit for me as a gamer. I was far more into imports, and I always considered myself more of a “fan” than a “journalist,” so I loved the excitement and enthusiasm the entire magazine always exuded.

Writing for GameFan was like having a conversation about video games with a friend, where you’d gush about the latest game you’d played that they really needed to also try, or have fun trashing some new title that was just a piece of junk. While the staff was a huge assortment of people from very different backgrounds, nearly everyone who worked there had that same passion for gaming, working there also helped cement beliefs I still hold to this day, such as how games should always be judged on their own merits, or how those of us in the media should always strive to be at least moderately skilled in as many genres as possible.

Ryan Lockhart: It was absolutely amazing, and terrifying, and horrible, and wonderful. it remains one of the most defining parts of my life, and one hell of a learning experience.

I came fresh from Babbage's, loved to write and made some great friends online (which turned into great offline friends as well), and a couple ended up at GameFan Magazine. I was given a shot, sent in some review samples, came in for an interview and was hired that day. They fired another editor at the same time, made him clear out his office while I was sitting in there, and that evening I had a huge crack in my truck’s windshield.

They fired another editor at the same time, made him clear out his office while I was sitting in there, and that evening I had a huge crack in my truck’s windshield

My original job was to help launch GameFan Online, which was a mess from day one – they had this Shockwave homepage that would take over a minute to load – but most of my day-to-day was begging Nick Des Barres and Casey Loe to translate Famitsu articles that we’d scan pictures from to make news stories. On the side, I wrote reviews and previews nobody else wanted, and eventually, I became managing editor of the magazine, which was sort of just herding cats (and having Nick run away from me when he saw that I was coming down the hall).

Most of my time there is a bit of a blur, but I remember the pure creative chaos that was Nick working – his office was covered with Japanese game posters, and he would lock himself in for hours, always seeking perfection in his screenshots and layout. Casey was always playing RPGs or watching Anime for articles; his office was barer, but that guy was a writing and layout machine. He and Nick were sort of the Yin and Yang of the soul of the magazine back then. And Dave’s office... it was like a Japanese game goods store; shelves covered with games and toys and stuffed animals and systems. Our hours were pretty nuts – the week before publishing many of us would stay awake for days, fuelled by chugging powdered tea for the caffeine spikes. We were young and crazy, but also had a passion for this magazine we loved.

I learned a lot of bad lessons there, though, and let stress overtake me more than a few times, which I’m sure burned some of my coworkers (Mollie, who took over GameFan Online after I dumped it on her, likely still holds some negative feelings for me to this day). My favourite personal screwing up story? Let’s just say don’t ever be involved in firing somebody if he’s also your roommate. I fought hard to get him back, though. Hah.

Can you give us some insight into the "Little Jap B*****ds" incident?

Mollie L Patterson: The incident happened a little under a year before I started at GameFan, so what I know I know from asking about it when I got there. (I remember hearing about the whole thing, and then running to a local store to grab a copy of the issue before they were gone.) From how I always understood it, it’s a less exciting – and far stupider – answer than some might expect.

Basically, one of the people that worked on the issues during the process of putting them together thought it was cute to use that text as the filler for figuring out how a layout would work, and how much text would fit into that layout. It’s not my place to say who it was, but it was someone that I never really knew too well, and someone that readers would probably have zero knowledge of. They weren’t a bad person from what I knew of them, just someone who had a regrettable sense of humour at times.

Casey Loe: Since GameFan prioritized the graphics of the page so much, pages often started with the layout. The layout person for that one just wrote a little blurb of text and copy-pasted it to fill out the page to get a feel for what the page would look like, and then sent it on to the writer to fill in the text. The problem was, the writer never actually replaced it with the real text.

GameFan had a real frat house vibe in those days. The assigned writer was a Japanese American and had a good relationship with the layout guy, and they were constantly ribbing each other, and the layout guy probably thought the writer would find it amusing. That was basically standard practice – the layout guy would always try to shock or amuse the writer with the placeholder text. Ironically, the guy who got burned by this was one of the more reserved and polite members of the staff. Had a different layout guy’s placeholder text slipped through, this would have been a very different scandal. I remember how stunned I was when I saw the official “hacking” explanation – it seemed like the truth would have been much more understandable and believable.

There are also stories that the GameFan offices got raided after a staff member pirated a review copy of Resident Evil 2 - is there any truth in this?

Mollie L Patterson: I’m actually not sure how much of this I’m allowed to talk about, but I’ll say that it wasn’t a staff member who pirated the game from how I know things to have gone down. It was someone outside the company who had access to our copy of the game for a short amount of time, which they shouldn’t have been given access to. There definitely was some fallout felt in the office, but for us editors, it was more in terms of how it complicated our relationship with Capcom for a while.

Ryan Lockhart: Yeah, I don’t want to get into the exact details, but somebody might have been “less than careful” with a review copy of the game, and Capcom digitally signed the discs, so it didn’t take long to figure out where the leak came from. All I remember for sure is one morning we arrived at the office and it was locked down for the day, somebody was arrested, and future review copies had to be literally microwaved or something once we were done to destroy them.

Another story involves drinks being spiked with acid – are these tales simply exaggerated or did they actually happen? Was drug-taking commonplace on the magazine?

Mollie L Patterson: The acid-spiked coffee definitely happened, but it was before my time. I was present for drug use in the office, but only to the extent that some of the guys would go up on the roof – we had access to it from part of our office – and smoke pot sometimes in the evening. Beyond that, though, I never myself saw any heavier drug use. Really, the biggest violation I knew of along those lines was one of the staff would constantly smoke cigarettes in their office, which was (and obviously still is) illegal in California.

There are a lot of stories from the office that were totally true, which, being fair, I think was probably the same for all similar publications back in that era. It may sound silly, but it was kind of a “rock and roll” type of vibe working for a magazine, since there wasn’t anything else out there gaming-related that could come close to the reach and exposure you were able to give video games. Publishers knew that, developers knew that, and we knew that.

Casey Loe: Incidentally, the person who spiked the coffee was the same person arrested for the mishandling of the ROM in the previous story. You have to understand that the people who founded the magazine were all old friends, many of whom had worked together, I believe, selling used cars. When Dave Halverson started his import game store, he hired his old friends to work at the warehouse and man the phones. Some of these people had never had a job outside of Dave Halverson’s orbit. When he transitioned to the magazine, he brought them along and found things for them to do. One of these people, in particular, was a very nice guy, but he had some issues and made a lot of poor choices. (By which I mean, multiple felonies.) He was fired from GameFan repeatedly but always ended up being rehired because of his friendship with Dave. He single-handedly generated most of GameFan’s most colourful stories.

(Since you didn’t mention it in the question, the acid story is this person drugging the office coffee pot, Dave Halverson unknowingly drinking it, and then writing an insane review of the Atari Jaguar game Cybermorph which ultimately went to print as-is. This happened before my time but every member of the staff from that time, including the culprit, agrees that it happened.)

Is it true that GameFan employees would race to the bank the moment they got their paycheque because often there wasn't enough money in the account to cover everyone's wages?

Mollie L Patterson: It really did happen that way. I used to describe it as something like the old American movie Cannonball Run, because at times it would be this race between a bunch of different cars, each of which had its own “team.” Since not everyone in the office had a car, and it’d be better to get you and your closes friends to the bank together, the staff tended to break out into small groups when it came time to go to the bank. For me, I was the closest with Mike Griffin (Glitch), Michael Hobbs (Substance D), and Dan Jevons (Knightmare), so we were always one group that made the runs together.

I don’t remember it being right away after I started, but more and more it ended up that, when our paychecks were handed out, we’d know they were probably worthless at that point. We’d call the bank to see how much money was in the account that our checks drew from – so often, in fact, that most of us came to remember the phone number and account number by heart – and it ended up that it’d be zero for at least the first half of nearly every payday. We’d keep pretending to be working hard, but we’d be calling the bank over and over, everyone in the office outside of the higher-ups like Dave, hoping to hear that money was now available.

The problem was, for whatever reason, it became routine that nowhere near enough money would be in the account. So, the moment you found out that money was in there, you needed to get to the bank as soon as possible. The other problem was, you’d need to get out of the office without raising suspicion. It sounds so ridiculous to write, but it was absolutely true – people would try to sneak themselves and their group out and into the car to head to the bank with as much of a head start as possible. If others caught on, or happened to call the bank at the exact same time, then it’d quickly turn into a race.

I remember standing in line at the bank, and the feeling of dread that’d come over me. Maybe I’d be in the back of the line, see other coworkers ahead of me, and know that there probably wouldn’t be enough to cash my check by the time I got up to the front. Maybe I was upfront, knowing I’d get money, but seeing all of my coworkers who might not. If you weren’t ahead of enough others to have your check go through, you just didn’t know when more money would be there – it might be later that day, maybe the next, maybe not for days.

It was always a competition to see who could get to the bank first to hopefully get paid, but you never hated anyone else if they got there first and you were left with nothing. None of the people having to do that were the reason our paychecks were screwed up, and everyone had to take care of themselves first. It was really awful for morale, though, especially the days when the first infusion of cash was low. There was no reason we should have had to fight over getting to the bank like that.

It was always a competition to see who could get to the bank first to hopefully get paid, but you never hated anyone else if they got there first and you were left with nothing

Casey Loe: This began in the period after the magazine was purchased by a company named Metropolis, which was a massively sleazy lad-mag publisher that promised to massively expand the business and was constantly playing the staff off one another. They were always asking us to expand into new ventures, which led to GameFan creating a lot of spin-off publications that only lasted a few issues. Magazine publishing, in the US at least, lends itself to sleazy business practices because newsstands pay you a percentage of the sales for whatever you ship to them at the point when they receive the product, so you can generate short-term revenue by “stuffing the channel” – sending lots of copies of magazines and strategy guides and whatever to newsstands – get the initial cheque, and then leave the newsstand with a bunch of junk they’ll never sell that ultimately gets destroyed. (Of course, it cost money to get all that content printed, but you can always switch printers and leave the first printer to try to collect.) I suspect that there was a lot of that sort of thing going on to try and make payroll.

Ryan Lockhart: Oh man, the bank run was the greatest (and also, frankly, the very worst) thing about working at GameFan during this time – payday was energetic, and I remember trying to hang out with people with the fastest cars (Terry and Waka, iirc) around the time checks were distributed to have the best chance of getting to the bank on time.

Mollie hit the feeling perfectly; it was Cannonball Run with all of us racing there, and then we’d be in the bank line counting staff in front of us, anxiously watching each person as they approached the teller. And more than once we’d see the sign, them leaving the counter and staring at us, head shaking, meaning it was time to leave and try again when David said there were more funds.

Most of the time it ended up fine, but there was one month when we had gas shut off for a day or two...

Despite the issues, GameFan remains a stand-out piece of video game history - what do you think made the magazine work as well as it did?

Mollie L Patterson: I think it was a few factors, really. If you look at some of the magazines that existed before GameFan, there was more of a slant toward “adult” publications – as in, magazines with a heavier amount of writing, deeper articles, and more of a focus on older readers, since I believe that was the market more tech-oriented publications were naturally slanted toward. Then, we started to see the market diversity, as new magazines cropped up that targeted different markets. You had EGM with a more “teens to 20s” type of edge to it, GamePro geared more toward younger readers, magazines specifically focusing on tips and strategy guides for the booming NES market, etc.

The thing about GameFan was that it was, as its name implied, about being a fan of games. GameFan was about having a deep passion for video games, and giving a chance to everything, even those games that a lot of other magazines quickly wrote off. Sure, it meant that, at times, we went way overboard in our hype or adoration of a particular title or franchise, but it also meant we’d often be the only one to appreciate a game that didn’t get the credit it deserved otherwise.

I’d always rather spend my time focusing on a great lesser-known game you might not hear about otherwise, than spend that time throwing another review for a bad game on the pile

One of the personal beliefs I took away from GameFan was the idea that, at its best, gaming media – the type not heavily focused on hardcore journalism – can be about leading gamers to games they never would have played otherwise. I definitely believe in giving honest reviews and knocking games that deserve it, but I’d always rather spend my time focusing on a great lesser-known game you might not hear about otherwise, than spend that time throwing another review for a bad game on the pile.

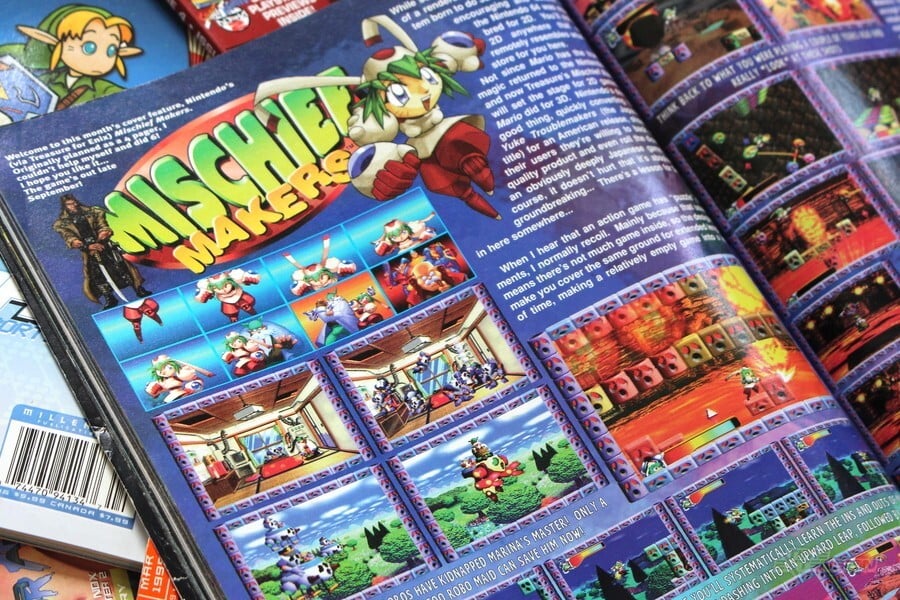

That, I think, was the heart and soul of GameFan; wanting to share that passion for video gaming with our readers, and hopefully expanding both their knowledge and horizons on what was out there. That especially came out through our deep focus on Japanese gaming, which rarely got attention outside of the big games and franchise. We covered games in our issues that you’d never have heard about otherwise in the West in that era, and that’s a huge part of why I myself became a reader before being staff. I remember finding out about barely-known import treasures like Keio Yugekitai through GameFan, and being blown away at some of the great games I’d never experience if I only focused on what was released in the States.

So, I really think it was the combination of strong, stand-out personalities, our passion for gaming as a whole no matter the franchise or genre, and our focus on imports. Oh, and probably also the fact that we took pride in having a staff of people who were great at gaming. For example, we had a number of hardcore fighting game players on staff, and I think that helped us shine a spotlight on some great fighting games that lesser-skilled media at other outlets would have been quicker to write off.

Casey Loe: When all of the other magazines were desperately fighting over Halo and Tony Hawk cover stories, GameFan always had a bunch of weird games on the cover you’d never heard of. Our fans tended to have what were considered niche interests at the time (RPGs, obscure platforms like the Atari Jaguar, anime-inspired games, etc.) and since we were on that same wavelength, we made the whole magazine about that. It turned out to be a pretty huge niche.

When I started there, I was kind of embarrassed by the magazine’s relentless positivity, but in time I came to understand that was one of its strengths too. Our readers were excited about games and wanted to see their own excitement for them reflected in the magazines they read.

Also, we simply had the best methods for capturing screenshots (some magazines eventually caught up over the years, others never did), we took a ton of pictures, and Dave insisted on printing on good quality paper, so the games looked fantastic. As much as I’d like to think the readers bought the magazine for our writing, the pictures were probably the real star of the show. I’m less sure about the benefits of its garish layout, with white text printed on colourful backgrounds and such. I remember proudly showing one of the first articles I wrote and designed to my elderly grandfather and him saying “I’m sorry… I can’t make any sense of this.”

Ryan Lockhart: Just to put a button on what was said above, at the end of the day GameFan was overly positive – it celebrated why we loved games and what made them fun – but there was another side to this too.

I personally had one of my very first reviews taken away from me, because it wasn’t positive enough – and the quote yelled at me “Do you know how many copies of these we have in the warehouse?” is still burned into my mind. You have to remember this magazine started out of the back room of a game store, so it always had a double purpose.

All of that said, 95% of what you read came from the heart – Dave, for all his faults, was truly a fan of the medium, and hired people that felt the same way. We loved games, and imports, and – hell – the idea of the magazine itself. It was unique and special; the magazine was heavy, the paper was thick, the layouts were beautifully garish with huge screenshots, and it covered these amazing games with such zeal – it was like having your best friend tell you about this incredible release they just played. It was made for us, for game fans.

Comments 67

Gamefan was awesome.

it's the reason i bought Suikoden

Think i still have some strategy guides from them as well.

HOLY COW!!!! I love you guys forever got this feature! 😂 This is a magazine I grew up reading and occasionally think about to this day. This got me thinking about how the big 3 each had official magazines. I used to like Nintendo Power, but thought it was kind of lame as a child. When the PlayStation came along, Sony’s magazine made NP seem incredibly lame. Same for the unofficial magazine. With the awesome demos! 😂 I think I avoided the official Xbox magazine was one I avoid. I think it was accused of being too biased towards Microsoft’s games. 🤷🏾♂️

Amazing write up. Thank you.

I read GameFan occasionally. I lost faith in them when Super Mario 64 came out and Tomb Raider got praised more to the point it won game of the year. Particularly as I mentioned in another article comment, N. Rox once reviewed Tomb Raider and then went on to praise the PlayStation and encouraged people that this was the killer app, and in the same review article said that if that wasn’t enough, Final Fantasy 7 was too. Shilling for Sony and praising another game in an unrelated genre for a review of a game—not professional to me, but hilarious in hindsight now that Square owns the Tomb Raider IP.

Thank you. Great read

Empty bank accounts and pirated games? sounds like a grave prediction of my adult life.

My friend owned a Diehard Gamefan gaming store (it was just like Gamestop) I am pretty sure there was a chain of them around the country. Good times, he couldn't compete with the big gaming stores so he only had it for 2 years but the place was full of Japanese consoles and games every week. He sold a ton of stuff. He just couldn't compete with the prices he paid for new games when compared to what Best Buy or other large stores were paying. He broke even on new games basically.

There’s a lot missing here which I’m privy too, since I was the actual person who bought the rights to DHGF in 2006. We started it back up in 2007 as a spin-off from 411mania and InsidePulse with Halverson’s blessing and lasted 10 years with some of the original staff joining in on occasion. We did a heavy tabletop emphasis and WotC and other RPG companies considered the coverage the start of the tabletop resurgence, which then other one time purely video game magazines and sites started joining in. That’s probably the highlight of DHGF 2.0 for me. That and getting to break the exclusive on HeartGold and SoulSilver. It was totally started as an homage to the original because we were all huge fans of the magazine.

The 2010 relaunch was a debacle for a lot of reasons, including the fact I was the rights holder and was one of the last to know. A few other people involved thought I was involved and when I expressed complete ignorance (because I was) a complete poop show occurred and the thing died quicker than it began. I’ve still got the emails. I felt bad because Dave had always been great on reaching out to me before, and had I known I’d have happily given my blessing and not asked for any piece of the pie. We were a not-for-profit and he knew I would let him do it for free. I guess he just got so caught up in trying to do the thing, he just forgot the most important piece of the puzzle?

Great article! I still have my full collection of Game Fan magazines.

I use to import all of my systems and games through Die Hard, Neo Geo, PlayStation and Sega Saturn, spent thousands of dollars there.

Wow. Very,VERY fond memories of this magazine. Especially the Mario 64, Mario Kart and Smash Bros copies. Once in a while I’ll have very odd dreams of getting Nintendo Power in the mail but like 4 or 5 magazines after being away and they’d be shoved into the mailbox. Good times the 90s

Loved this magazine when I was younger. I still have a few issues laying around to this day, and I still enjoy reading 'em. Thanks for the great article...

Fantastic read. GameFan, Super Play and C&VG (yellow pages in the middle era) were the standout magazines of a wonderful era. So much passion in each magazine with amazing new games and genres appearing on a monthly basis. Awesome times and memories!

I was very lucky in the 90s that my newsagent in the UK stocked Gamefan, EGM and Gamepro so I had access to these great magazines.

Along with SuperPlay, CVG etc. I probably bought 10 magazines a month.

Great days and I genuinely miss a newsagent shelf full of gaming magazines.

Sure, sites like Nintendolife etc. keep me up to date with news, reviews and so on but the standard of journalism in general is utter drivel.

@Rodan2000 My local newsagent stocked all those magazines too, was really interesting to compare them to the UK mags of the period. The irony is that GF had a lot of ex-EMAP guys working on it!

That was because there was hardly internet @ homeholds.. most of weren't even aware of emulators. Sure my PS1 got a chip later, but when I like a game I have to buy it. It's pitty that the physical releases are so little now. I have so many games on my wishlist to have a physical edition

I miss magazines

Well this was a blast from the past. I remember GameFan being my least favorite of the magazines of that era. Looking at that Mario 64 cover (which is one of the few I vividly remember), I seem to recall the covers being obnoxiously too overdone at times. Though the one cover that seems to stand out in my memory is the one with Vectorman on it. Only because I remember that particular issue hanging around my house for whatever reason long after it's expiration date

Holy hell, what a ride! Man, what I'd give to be there as all went down...

Fantastic write-up and one millions thanks to everyone who made it happen. Do more of this, please... it's easily your best work!

@asmi8803 I do too. Gaming magazines were one of the things I looked forward to buying when I got my allowance and ultimately when I was old enough to start working.

I also miss the anticipation of discovering what the next big game or story was going to be. I mean, I love the immediacy of the internet. However, there was nothing like seeing a magazine cover and seeing a new game or console revealed for the first time. It was a really great time to be a gamer

Great article. I still have some Gamefans lying around somewhere, I should dig em out. There wasn't many places selling American games mags over here.

Interesting story, but am I the only who has noticed that so many of these kinds of retrospective articles read essentially the same? Wild behind-the-scenes stories, revelation that the brilliant guy who started it all may have been a little crazy and unethical, then it all suddenly went down in flames leaving former employees with a sense of nostalgia about what a great or at least interesting experience it was.

Very nice interview. I remember reading a Gamefan in summer 1995 when trying to decide between the PlayStation and the Saturn, having stopped playing games for some time during my high school years.

I remember loving this magazine when I was a kid. This was an awesome write up. This makes me miss working on magazines and newspapers.

I bought Macross Scrambled Valkyrie from a Die Hard store. I had a list of their locations and just called all of them until I found it. I had to overnight a payment to them and they shipped it. This was early internet so no easy way for a 20 year old to do this. I still own that copy. Great memory. I loved the magazine of course too!

Off topic but, looking at one caption in the article reminds me I never got to play Mischief Makers. Please re-release Treasure.

One of the main things that stuck out about GF to me, during the 16-bit era at least, was they were not afraid to call a spade a spade. They were the first US-based print magazine I ever read that would trash a legitimately poor game. Gamepro, EGM, and Nintendo Power would write an entire single page review of a crappy game, glossing over or barely mentioning bad points, and leave only a lackluster final review score as an indication of low quality.

Gamefan didn't care to comedically trash a game, and was written how a normal game player would talk to another, not like a PR driven doublespeak robot to avoid losing advertising revenue.

I believe this has been one of this site's best features ever. Such an amazing read that made me appreciate what we used to have even more. Something like this is just so hard to come by nowadays, especially when it comes to video games media. These guys had soul, and they made GameFan with it.

It's just kind of hard to put into words, this was such an amazing piece. Thank you.

@Damo I think the UK magazines rather than the US ones have definitely stood the test of time though, mags such as SuperPlay, Maximum etc are infinitely readable ( though it may be through nostalgia tinged eyes no doubt ).

Great article. Best one I’ve read on this site. Thanks Damo

Great article, brings back memories of reading this magazine. Loved their Japanese games & anime coverage.

If you guys wanna do more of this sort of looking back on the games magazines of yore, you guys should try and nterview Chris Slate (who does the Nintendo Power Podcasts).

Although he was most notably the last lead editor for Nintendo Power, he was also the one behind the equally zany and hilariously cult classic games magazine, "Game Players" / "Ultra Game Players" from I think between 1993 and 1996.

Game Players wasn't quite as well known as Game Pro and the like, but like GameFan, Game Players was extremely irreverent, "edgy" (especially for the time), bizarrely clever, and funny. It would have been like... if Adult Swim had published a printed videogame magazine...but long before Adult Swim was even a thing.

I wonder Slate and the others were fans of GameFans - I can kind of see that being the case.

But yeah, Chris Slate would be an awesome interview anyway, as he had been in the videogames publishing industry for decades and is to this very day employed by Nintendo.

@Severian You lost faith because they didn't play to your biases? Says more about you than them.

I admit I used to get them mixed up with GamePro. I think I had a GameFan issue with Earthworm Jim as the cover story but usually I was more of an EGM reader.

@Magitek_Knight if by my “bias” you mean my understanding of “professionalism”, then that sure says a lot about your understanding of professionalism. 😁

@Severian Okay number 1: it was basically a fanzine with national circulation so professionalism doesn't really come into it. Did you read the article? They don't sound much like Film Comment.

Two: whatever your hateboner is for, Sony, Tomb Raider, what have you, I don't see how it matters.

@Andy_Witmyer

Game Players was indeed interesting...their humor and open disdain for fans writing letters, and the tone certainly made them read like the writers of Mad Magazine had a party with weird writers like Hunter S. Thompson and Charles Bukowski.

@Magitek_Knight “Hate Boner”. Classy ad hominem attack that makes no relevant argument to support your case that also happens to be a straw man tactic. 😁

I read the article and again don’t see what you read to conclude things.

Let us try the adult way and I will speak to your two points (dull as they may be).

1. Professionalism doesn’t get thrown out the window just because it’s a fanzine. Yes, they operated like a frat party in a garage, but there are still standards to adhere to for any journalistic endeavor. If anything, the levels of professionalism show more in a tight-knit group there, or “By the fruits ye shall be known.”

2. What hate for Sony or Tomb Raider? If someone reviews a game, focus on the game and refer to other games relevant for comparison. What N. Rox did in the Tomb Raider review was bring in an unrelated game from a totally different genre to support his argument to buy a PlayStation in order to play Tomb Raider.

That’s like saying “I encourage you to buy adult diapers so that you can enjoy laxatives in your coffee” while writing an article about talcum powder and its benefits of dealing with genital rashes.

No hate for Sony at all or Tomb Raider—just not interested in some fanboy whose review sounds like the lunchtime console wars arguments in middle school instead of a game review by its own merits—something GameFan was known for as indicated here so it would look at games more appreciatively that were overlooked by larger publications. 😁

In other words: N. Rox just sounds like the same establishment the magazine attempted to run contrary to then. 🤪

@Severian Okay, professor.

I don't know about your experience with zines but most I've been exposed to (and their digital descendants) have been pretty unprofessional though most try to put up a facade of "we know what we're doing/what we're talking about". I don't think there are many places more difficult to claim credentials or professionalism than talking about video games.

And I wouldn't say totally unrelated, as SM64 and Tomb Raider are both, broadly speaking, focused on platforming and traversal.

@Magitek_Knight Sure thing, college student.

The Super Mario 64 comparison is relevant. The Final Fantasy 7 shilling is not.

My experience with zines is that I actually made some before becoming an actual journalist for a while, and if you didn’t know, the past few years, zine culture has been in resurgence due to the love for print and the niche readership behind them. Go to a place like Green Apple books in San Francisco and whole shelves are filled with zines—not just xerox and staple runs, but published in standard glossy.

Also, talking about professionalism and video games is not an oxymoron at all, even when writing about video games. Professionalism is a form of conduct that doesn’t disappear because of the field and niche.

Lastly, before you bring in more accusations of Sony hate from me, please do see my profile and contributions at push square, which has a large number of games almost as large as my Nintendo collection.

Was this put together because it at all resembles working at NintendoLife? Have you been drugged or had pay withheld due to incompetence? Is this a hidden message to your readers?

@Severian I've worked in writing myself. I never considered myself a journalist, though.

I mean professionalism doesn't necessarily disappear but the expectation that it will be there is also a bit of a bold assumption when dealing with amateur or enthusiast press. This was exemplified by a few writers we had at a site I wrote for- specifically they treated a collaborative site like their personal blog and didn't bother adhering to our established style guide.

Anyway, I misinterpreted your comments a bit and I apologize for doing so.

@Magitek_Knight apology accepted.

As for amateurs and dilettantes—oh boy, I had people older than me acting more childish than the college interns at times, particularly those who were there due to nepotism.

Outstanding article! GameFan is my all-time favorite gaming magazine, and I’m still trying to track down some copies I need to complete my collection. I didn’t always agree with them, but every issue was a fun, interesting read.

Gamefan was awesome together with CVG

Used to order from DieHard all the time, probably the most memorable thing I got was the Super Famicom Street Fighter 2 before the American version released. Even visited the original store on vacation once. Good times. Thanks for this article!

The Halversons (both them, the good cop and the bad cop) owe more than two dozen people tens of thousands of dollars. Not even kidding

If you want the real story on them, you need to hire a lawyer and interview all his ex-staff. They're not hard to find and very willing to talk

I hope THAT story gets told because that's the real story

Getting a new issue of Gamefan was like Christmas eve. You knew you were in for a good time with all of their crazy screenshots and coverage of cool import games. I believe they also made the best player's guides? I have fond memories of a Phantasy Star Online guide that had layouts like the magazine.

@Alexlucard That's interesting! Do you have any posts detailing more of the history of our relaunch/attempted relaunch.

I always loved DHGF from back in the day...

I loved GameFan! Always had the best RPG news (back in the days when there was a real drought in the US) and loved their in-depth coverage of games and systems.

Not sure why people love hating on the Atari Jaguar and Cypermorph (other than the fact it ultimately failed and everybody likes to think they are superior). The Jag had awesome games I still fire up occasionally, the best known being Tempest 2000. At the time the 3DO had flashier graphics, but the games sucked. At launch, Cybermorph was the superior game. Too bad the Tramiel's didn't know how to really run a business.

One of my biggest regrets is giving away my nearly complete run of GameFan.

This was fantastic. Gamefan is my favorite gaming mag of all time. Would love to know what Dave is up to.

As someone from the UK, I’d never heard of these magazines before, but it was still a very interesting read. Thanks!

Once a favorite mag of mine! I liked it even better than EGM & Gamepro! Loved the art style and the content! Looked forward to it every month! I miss those old days! 😕

Gamefan was THE magazine for everyone into video games around my area (and that includes the kids). I probably latched on within the first few months of national distribution and followed the magazine up until about the middle of 1997.

Thankfully, most of their audience had just lived through the Image Comics explosion and so their sometimes spotty publishing schedule was met with shrugs.

One would think that this was "pre the internet", but I remember talking with Nick (who was VERY young) and a couple of others on Prodigy and I'm sure members of the staff had either that or Compuserve or Qualcomm or whatever and BBS access. Anyway, all of the crazy stories we know about today, we also knew about as they happened. I, personally, didn't get those tales from the horses mouth, but the "grown ups" (probably like 19 years old) at Babbages, half the country away, seemed to know every inner detail. TBH, how did these tales not spill onto networks and spread through the ears and mouths of video game retailers? The Cybermorph review was right there for everybody to read. :0

I didn't read GameFan much but I was a subscriber at various points to GamePro, Nintendo Power, Game Players, and PSM, and regularly bought other magazines at my local supermarket and book stores as a kid/teen. The '90s were truly a golden age for game magazines.

I agree with the others who say you should do a follow-up for Game Players, that would be of more interest to me.

@Andy_Witmyer

That'd be a fantastic interview. Chris Slate also was Editor in Chief at PSM for a long time. Would be interesting to get his take on the whole Nintendo-Sony rivalry from his perspective as a journalists at the time it started and later on when he flipped sides and ended up at Nintendo Power.

When I was real young and starting to truly appreciate gaming, GameFan was in my top 5 favorite mags. I didn't subscribe like I did to EGM and GamePro but if I was in a store that happened to have the new issue I'd definitely buy it. The style, the layout was different but there was something about it I enjoyed a lot.

This was an awesome read. Thank you! I’ve never read this mag, it didn’t seem to make it to any newsagents that I used to frequent here in Australia otherwise I’m sure i would have.

I liked DieHard GameFan more back when EGM was starting to focus more on mainstream and GamePro was nothing but mainstream. GameFan would continue to cover arcade games, NEOGEO, and what's hot in Japan, including anime, all throughout the mid 90's. But man, magazine collecting was getting expensive for me back then, still earning minimum wage+, and buying EGM, EGM2, GamePro, DieHard GameFan, and EDGE in the late 90's every month took a bit out of me, especially when I started college. I threw a lot of them out by 2000, unfortunately.

I was their Japanese editor at the very end. It was a mess. None of the other writers could make deadline. Dave Halverson kept asking me to go into Akihabara and take pictures of toys and figures, not for the magazine, but so he could pick out stuff to buy. Still, I appreciate having the ability to say that I worked for GameFan.

Great story. They sold GameFan at the local pharmacy when I was in my early teens and I always looked forward to picking up the newest issue. I was bummed when the magazine ended.

It's amazing to hear some of the behind the scenes dirt of how it came together and ultimately fell apart.

Was that wrong? Should I have not put acid in the office coffee pot?

greatest thing about gamefan was its amazing paper quality, screenshots and layout, as well as its "fun" readability. today's modern version of gamefan would be retro gamer, a magazine i really enjoy browsing through.

i LOVED the marvel vs. capcom issue (not on the cover but inside). the layout was so well done and i loved the screenshots and overall look of that.

Dang that's kinda wild, in good and bad ways.

Thank you for helping me wax nostalgic for Diehard GameFan magazine. I absolutely adored this magazine. I probably started reading GF around '93 or so but by the time of the 32-bit machines coming out it was my favorite mag. The layouts were a mess but in a great, look at it for hours kinda way. I'm so sad I tossed all of my old gaming mags, but 20 years ago I thought I was done with gaming forever. Then I got old and nostalgia became an addiction. This is such a great piece on a great piece of video game history and my personal past for this mag has grown fond again.

Oh and by looking at the comments this mag was huge with a lot of people. That makes me happy.

Amazing magazine, the reviews, screenshots, the passion for consoles was evident. Hard to get in the UK, luckily WH smiths managed to get issues for me. Best Magazine ever in my opinion along with Mean Machines. Unfortunately both didn't last. Probably for the best really, because that was the golden age of gaming. I'm sure they would of lost there magic in today's era.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...