It’s hard to imagine a time before Barbie was a multi-media megastar, but at the start of the '90s, she had only appeared in one game that had ultimately failed to live up to the expectations of its publisher, Epyx: Barbie (1984) for the Commodore 64.

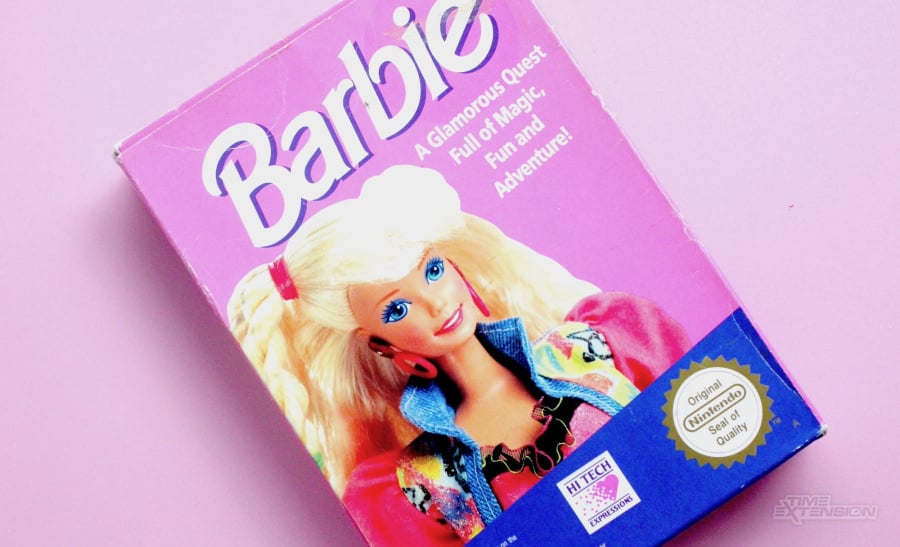

Barbie's creator Mattel didn't yet see the benefit of making its own video games based on the character but was instead happy to license her out to other developers and publishers to take a shot. For a number of years, this approach resulted in a fat load of nothing, but then in 1990, the New York-based games publisher Hi-Tech Expressions got in touch with an offer to create what would become Barbie's first video game for a Nintendo system: 1991's Barbie for the NES.

Developed in partnership with the New Jersey studio Imagineering, Barbie (1991) was an attempt at making a Mario-style platformer that would hopefully appeal to girl gamers, but it was by no means a typical example of the platforming genre. Barbie doesn’t jump on enemies or perform actions herself, instead commanding a small army of animals and sentient fast food to carry out the tasks for her. It's not exactly the type of gameplay you’d expect from a mascot platformer and allegedly came about due to Mattel’s reluctance to let the licensees do anything that could potentially be construed as unflattering or “unladylike”.

Over the last year, Time Extension spoke to a group of ex-Hi-Tech Expressions and Imagineering staff to uncover more about this unusual tie-in for the NES and some of the interesting demands that led to its design. We also took a look at its legacy too, in relation to other Barbie games, including its partial remake/spin-off Barbie: Game Girl for the Nintendo Game Boy.

The story begins at Hi-Tech Expressions.

Hi-Tech & Games For Girls

In 1987, the New York card-making company Thoughtware Expressions, under the leadership of businessman Hank Kaplan, rebranded itself to Hi-Tech Expressions and started publishing licensed children's games for computers based on Sesame Street characters like Grover and Big Bird. The company at the time was located at 584 Broadway between Houston and Prince in Lower Manhattan and shared the building with a number of other businesses including a erotic film company named Femme Productions (owned by the erotic filmmaker Candida Royalle).

Over the next few years, Hi-Tech made a name for itself releasing a bunch of titles for MS-DOS computers, the Apple II, and the Commodore 64, but Kaplan had dreams of expanding the business and getting into creating games for the Nintendo Entertainment System. So he tasked his son, Barry Kaplan (who knew more about video games), with hiring people who could help facilitate the company's growth.

The younger Kaplan, who was a regular of the New York City punk scene at CGBGs, subsequently hired a bunch of his musician friends, who in turn recommended some of their own pals for other vacant positions within the company. This led to a popular saying among those who were employed at the publisher that “To work at Hi-Tech, you have to play an instrument.” Among those hired during this period included the musicians Asif Chaudhri and Billy Pidgeon who became producers, as well as the saxophonist Dan Feinstein (who had previously played in a group with the former New York Dolls guitarist Sylvain Sylvain).

Feinstein tells Time Extension, "I needed some kind of work. Anything, so I’d be free to play [music] at night. Billy [Pidgeon] was like ‘You fool around with computers, right? You can answer phones.’ So I did it and for a month they yelled the answers across [the room] to me. After about a month, I realized 'Oh, these people weren’t plugging in their machines'. [...] People would call up for help and I would ask them whether they had them plugged in. Nine times out of ten they didn’t."

Feinstein initially came on board as a member of Hi-Tech's product support in 1990 but quickly found himself stepping into a producer role after only half a year at the company.

"After about six months, there was [some] turnover," says Feinstein. "Two of the producers quit and one of them had been fired — I don’t remember what the circumstances were. Hank Kaplan, the owner, came up to me and said, ‘You know how to produce right?’ He said, ‘I’ll offer you —‘ and it was something like three times what I’d been making for years. So, I said, ‘Sure, I know how to produce!’"

At the time, Hi-Tech was still primarily releasing games marketed towards children, but also recognized a need to expand into other areas to maintain the company's growth. So it worked out a deal with Mattel to produce a series of games based on Barbie, in order to try and tap into the growing market for girl gamers. And Feinstein was put in place as the producer.

Today, girls are playing multiplayer shoot ‘em ups online and they are as good as anybody but at the time the machines were considered like boys' stuff and they wanted to bring girls in.

"The idea [with Barbie] was — and it sounds so sexist now — was that it was ‘the first all-girls game’," says Feinstein. "Today, girls are playing multiplayer shoot ‘em ups online and they are as good as anybody but at the time the machines were considered like boys' stuff and they wanted to bring girls in."

So Hi-Tech went searching for a development partner for the project, and luckily for the team, a perfect one was waiting, just one state over, across the George Washington Bridge.

Imagineering was the development division of the publisher Absolute Entertainment and was situated at the time next to a noisy train station in Glen Rock, New Jersey. The brothers and former Activision designers Garry and Dan Kitchen were in charge of running the company, alongside their brother-in-law Alex De Meo, which resulted in a family atmosphere where employees were often invited to barbecues and gatherings outside of work, in order to socialize and relax.

In the past, the studio had a few NES titles under its belt, including David Crane’s A Boy And His Blob and Garry Kitchen’s Battletank, as well as some work-for-hire projects like Ghostbusters II. As a result, it seemed pretty much like a shoo-in to help develop the project. The clincher, though, was that one of its programmers Henry C Will IV had been trying to lobby the owners to acquire the rights themselves, after recognizing the potential for a game based on the license.

Henry Will IV was a programmer who had previously worked on the AV8B harrier jump jet before making the switch to video games in the early-to-mid '80s, joining James Wickstead Design Associates and later Imagineering. He was already familiar with Epyx's earlier release for the Commodore 64 and wanted to take his own swing at bringing the character to video game fans, partially inspired by his two daughters and their love of Barbie.

Will tells Time Extension, "When I worked at Imagineering, at that point I had two daughters and they loved playing with their Barbies. I said, ‘I want to work on a Barbie game sometime because my girls love playing with Barbies all the time. We should do a Barbie game.’ I kept telling them that. Then they went away to a tradeshow one year — one of the CES shows — and when they came back they said, ‘Guess what Henry? We’ve got a contract to work on a Barbie game and you’re going to work on it since you’ve been asking all this time.'"

...everyone else in the office was laughing about it: ‘You’re doing a girl’s game?’ Nobody really wanted to do it.

The owners signed a contract with Hi-Tech to be the main developer on Barbie, with Will being positioned as its lead programmer. But there were some within Imagineering, who weren't exactly over the moon at the idea of working on such a girl-centric property. Another programmer on the project Tony Chung Lau can remember people in the office laughing and joking about the license when it was first brought up, though, as he tells Time Extension, he personally was excited to get involved and see what he could learn from working with Will.

"I just followed Henry’s lead," says Lau. "You know, he taught me a lot of things. But you are right! At the time, everyone else in the office was laughing about it: ‘You’re doing a girl’s game?’ Nobody really wanted to do it, but that could just be what they were saying. I’m not sure if they were assigned to it that they would have minded. But the general atmosphere was people were joking about, ‘Oh, you’re doing a Barbie game.’"

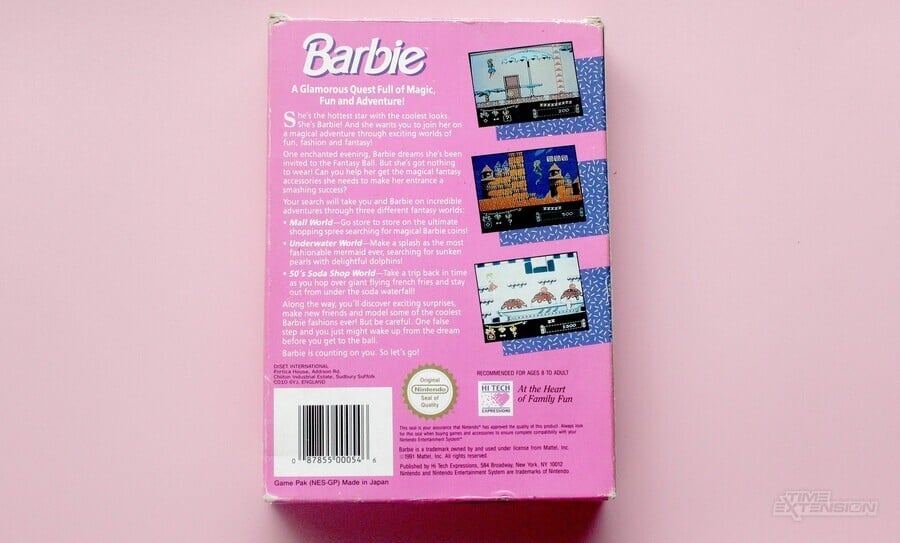

Together with Feinstein, Will, Lau, Alex De Meo, and an individual named Barry Marx, put together a pitch for the game, with the idea being to create a platformer, with Mario as the key inspiration. The ultimate goal of the game would be to put together an outfit to meet Ken, with Barbie having to collect an accessory from three different worlds themed after a shopping mall, an underwater kingdom, and a 50s soda shop.

Will explains, "Back then, Mario games were really big and you’re fighting and you play through a level and then you’ve got a boss monster, so we were trying to find ways to kind of mimic that whole idea of going through a level and then having some kind of a boss monster with a lot of our games. [...] It was fun because a lot of time designs were dictated to us and we were able to do a lot of creative input on that game too. Out of the three owners, Alex DeMeo was the one that was the head of that project, so I spent a lot of time with him telling him ideas that I thought we should use in the game, and he would come up with ideas too. It was fun to have some creative input on that, you know. So, a lot of the time, he might come out with or figure out a theme or something, but then I would be able to go into the detail of designing it and how exactly will that work in a game or how exactly will we lay that out in a level or whatever."

Things were all looking positive heading into the development of the game, but there was just one small problem: getting Mattel to sign off on their ideas.

Making The Game

As the licensor, Mattel's idea of a Barbie game was all about having the character stand still, look pretty, and shop for clothes. So when Hi-Tech Expressions and Imagineering proposed doing something a bit more active with the character, the toymaker had some reservations.

As Feinstein recalls, "They’d never had any of their characters move or throw things or do any action. To them, Barbie had her hands at her side. She was dressed very nicely and she just walked. [...] Barbie doesn’t have enemies, Barbie doesn’t jump, Barbie doesn’t die. Barbie doesn’t do anything but suck. [..] As a boy, we used to pull the arms off [all the Barbies in my friend’s sister’s room and stuff] and put the arms where the legs were and the legs where the arms were, or pop the heads off. We thought Barbie could do everything. But when we went to Mattel, we had to negotiate. We had to be diplomatic. I had to learn their Barbie product file inside out and I had to work with them to accept certain concepts for video games."

Feinstein recalls constantly having to try to sneak design decisions past Mattel in order to get them into the game, but Imagineering's developers claim this was pretty much par for the course when working with licenses.

"When you deal with licenses, there’s always back and forth," says Lau. "Always! I don’t remember exactly what it was for Barbie, but it was very normal to go back and forth and to do changes. I remember that more for projects that I did after I left the company. I also dealt with other licensors like Disney. Disney when I dealt with them (not at Imagineering) was also very strict on many things. So, it’s very common in this industry when you deal with licenses, but the thing is you always have to deal with them because it’s always projects that use licenses that sell. If they don’t, it’s very difficult to sell them."

Will tells Time Extension, "I do remember them telling us Barbie can’t die, so we had to work around that. But I’m glad they said that, because I was never crazy about that idea in games anyway that things got killed and then you bring them back to life." He continues, laughing, "I’m a Christian so I don’t really believe in reincarnation. So I was kind of happy that they put that restriction in and we found a way around it, you know. You’re right though. I remember the whole thing with the enemies. You couldn’t kill the enemies too. That type of thing."

In order to satisfy Mattel's demands, the publisher and developer didn't scrap its idea for a platformer but instead employed some clever tricks to design around them. First of all, they set the game inside a dream, so instead of dying, Barbie would simply wake up after taking too much damage. As for enemies, there were technically none, with the developer and publisher pitting Barbie against a bunch of inanimate objects, which had magically come to life, including ball cages, items of clothing, and pizza ovens. Barbie also wasn't required to fight at any point either, instead being able to throw magic crystals to call upon a bunch of animal pals or enchanted fast food to do her bidding for her.

As Feinstein remembers: “We used Tennis rackets [as enemies] and she could toss things to her friends who could do certain things. Like her little bunny friends or rabbit friends or doggy friends who could take something and do something with it. [...] But the biggest problem for them was Barbie’s look. [It all] had to fit onto an 8-bit system."

Barbie's sprite in the finished game doesn't look like your typical NES character, being much taller and more colourful than average. As Lau confirms, this is because Imagineering combined multiple sprites in order to get around the NES's four-color limit, a trick it often employed in the development of many of its games.

Lau recalls, "For the main character, we composed it with multiple sprites to form an object or character. This was done not only to create more colors but also to save memory since different sprite combinations can be reused to form new animations instead of creating new frames for each and every move."

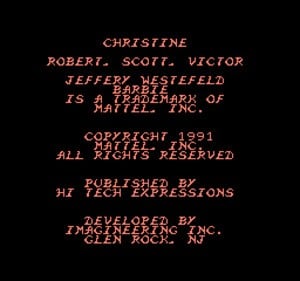

In total, Barbie was in development for roughly a year and was, much like many of Imagineering’s projects, subject to long hours spent at the office. For many of the team, this meant time spent away from family. So as a way of compensating, some of the developers hid a secret message hidden behind a series of inputs on the copyright screen (as discovered by The Cutting Room Floor), which included the names of family and friends.

Will recalls, “A lot of the time what we would do when we were making games is we would have Easter Eggs as they call them and we would put like if you jump on this particular thing and face the other way or whatever – things people wouldn’t usually do in the game – then we would have something pop out that would have our kids initials in them or something like this. When you worked on these video games, a lot of times you were working really long hours, so you kind of wanted to give some acknowledgment to your family as they were putting up with not seeing you for a long period of time, you know. So, that was one way that we could do that and give them a little acknowledgment that we still cared about them even though we were working such long hours.“

When we ask Lau, he adds, “Some of those names are my family and friends. We all did them. I guess I was so dumb I never thought people would be able to find them, but apparently, they did. Did you say Jeffery Westefeld? I don’t recall that, so that might have been a name put in by another programmer – probably Henry. But yeah, all those names are friends of mine or family."

The Legacy Of Barbie NES

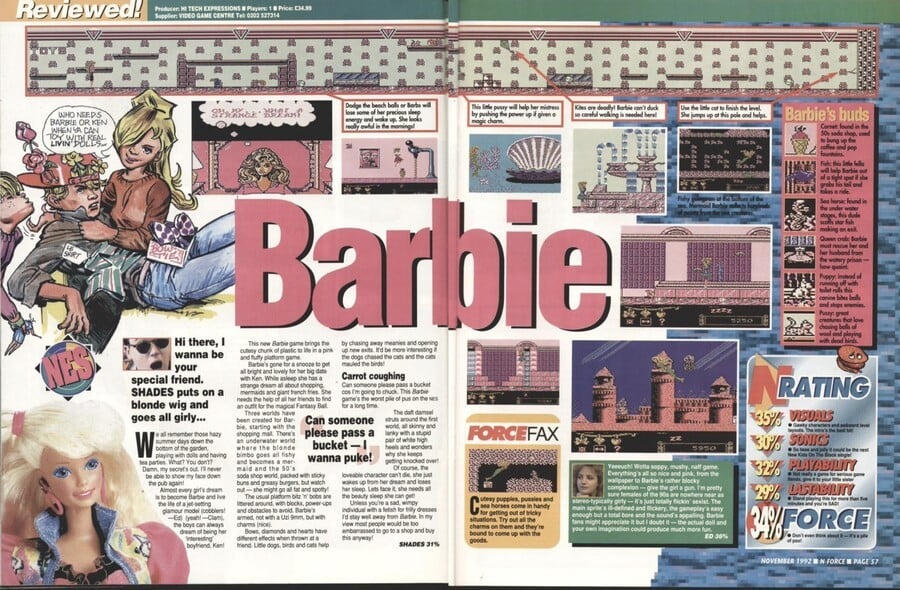

Barbie for the NES was released in 1991, with a conversion for MS-DOS also coming out that same year (developed by Sean Michael Puckett and Terri L. Puckett). The NES version was the platform that was reviewed by most of the gaming outlets, but the critiques weren't exactly glowing. In North America, the Nintendo magazine Nintendo Power gave the game average scores across the board for its graphics, play control, challenge, and fun, while the British publications were far harsher on the title, criticizing the graphics and sound and going out of their way to insult anyone who played it.

The Future all-formats magazine Total!, for instance, gave Barbie a 19% and wrote that “If you like this game you must be dead", while a November 1992 issue of N-Force went one step further calling the game “the worst pile of pus on the NES for a long time” before suggesting “Unless you’re a sad, wimpy individual with a fetish for frilly dresses I’d stay well away from Barbie.”

The game wasn't just the source of intense criticism from male game journalists either, with former Mattel executive producer Nancie S. Martin later calling it an example of "pink software" in the book From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender In Computer Games, released in the year 2000.

...this didn't really address fundamentally the way girls play. I mean, video games were your typical pink software. They were boys' games made pink.

In that interview, she claims: "[...]in the early 1990s Mattel licensed out Barbie for a couple of video games and for a sort of Director kind of CD-ROM, but it was always other companies doing the work. The people within Mattel who were supervising it at that time just wanted to be sure that Barbie looked ok. And she looked ok, and the copy on the box was ok, and they said "Fine, you can release this." But this didn't really address fundamentally the way girls play. I mean, video games were your typical pink software. They were boys' games made pink."

Despite these negative responses, the game sold well, leading an upcoming New York publisher named Acclaim to headhunt its producer, Feinstein, for its rapidly growing company. As for Imagineering, it folded into Absolute Entertainment shortly after Barbie was released as part of an internal restructuring but continued working on licensed games with Hi-Tech. This included a remake/spin-off of the NES game called Barbie: Game Girl for the Nintendo Game Boy. Game Girl featured roughly the same premise as the NES game and shared some boss designs, but included entirely different level layouts and an expanded move-set. With Feinstein gone, Billy Pidgeon stepped up to produce, while Will and De Meo returned as the game's main designers.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the game today, though, is that it was actually the first title that the Dead Space and The Callisto Protocol creator Glen Schofield ever worked on, something which he has brought up many times before in interviews and on podcasts.

Speaking about how he got the job, Schofield tells us, "A friend of mine at the time, Mike Sullivan, called and said Absolute was looking for a computer artist. Mike and I learned computer art together at a place called Digital Learning Systems where we created animated tutorials for IBM, ATT, Panasonic, and Tandy (Radio Shack) personal computers. I went in for an interview at Absolute where Garry Kitchen asked me to work for free for two weeks creating a couple of levels for a potential Wizard of Oz game. I had a crash course in using D-paint. After working those two weeks for free, I got the job. I think I was employee number 14.

"I designed the levels and created the art tiles [on Game Girl]. Back then the artist was the designer too. I don’t remember following the NES that much at all. I studied Barbie in the toy stores and bought a couple of dolls; I just wanted to do a great job because I was the new guy. The other artists thought it would be a big joke to give the new guy (me) the Barbie Game Girl. But I didn’t care."

Strangely, whereas Mattel was extremely overbearing when it came to the NES original, it was much more hands-off and relaxed with the portable version, leading the team to be able to implement a lot of ideas it had been unable to in the original. Barbie can obtain power-ups that let her perform somersaults, for instance; attack alien-like enemies; and even fall to her death as the game no longer takes place inside of a dream.

We ask Schofield if he remembers receiving any feedback from Mattel while working on the game and he replies, "I never found Mattel to be a problem. As long as I worked within their guidelines and took their property seriously, they left me alone. They just wanted quality for their property. If I remember correctly they didn’t have any changes on their final review. After that game, [Absolute] made me art director."

The only potential challenge that Will remembers was translating the graphics and even that, he claims, didn't seem to be much of a problem: "The Game Boy is kind of monochrome so I think from an artist’s viewpoint that was a little bit more challenging. You can’t do the same that you can do with the NES in terms of the colours and everything, so that was somewhat of a restriction and, you know, the screen isn’t as big on the Game Boy. But I don’t remember there being quite as many difficulties. I think there were some technical restrictions about how much we could put on the screen at one time and that type of thing, but I don’t remember having a particularly difficult time pulling that off, you know."

Barbie: Game Girl was released one year after the NES original in 1992, but the critical reception wasn't much better. Nintendo Power was again fairly enthusiastic about the release with one of its reviewers calling it "perfect for Barbie fans", while a German magazine named Aktueller Software Markt gave it a low score of 3 out of 12, claiming that it wasn't a particularly good game for girls and that players would be far better off playing with a real doll than spending 70 marks on the title.

As research for this article, we played both games and are inclined to err more on the side of Nintendo Power's assessment. While the games certainly aren't some of the best titles these Nintendo platforms have to offer, they are perfectly fine with some interesting ideas thrown in to keep them engaging. The developers aren't ashamed of their work either and are glad to have played a small part in bringing the doll to more players.

"To this day I’m glad they put me on Barbie," says Schofield. "I’m [also] glad I didn’t do the NES, that was my least favorite console to work on."

"I have grandchildren now," says Will, "So my son has been pulling out some of the old consoles and stuff like that and he wanted to get out, I think, the Super Nintendo and N64. He was pulling out all these consoles and stuff that we have lying around in storage here in the house, and he pulled out the Game Boy, and the kids put in the Barbie cartridge and they were passing that one around for a while in the family and playing the game. So it was kind of cool to see the grandkids playing it."

Following the release of Game Girl, Hi-Tech ended up releasing two more Barbie games without the involvement of Imagineering. This included 1994's Barbie: Super Model (developed by Tahoe Software Productions) for the Sega Mega Drive, SNES, and MS-DOS and the point-and-click CD-ROM game Barbie And Her Magical House.

Another Barbie game was planned, called Barbie: Vacation Adventure, which was being developed at the Manchester studio Software Creations for both the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, though this project was eventually cancelled for undisclosed reasons. The game seemed to be pretty finished at the time too, with the magazine GamePro reviewing the Genesis version of the game and describing it as "fun and educational" in their write-up.

While Barbie for the Commodore 64 undoubtedly brought the character into the world of video games, and Barbie Fashion Designer a few years later helped transform the doll into an unexpected success story, Barbie for the NES marked her arrival on home consoles and helped to broaden what a Barbie game could potentially be. It is often forgotten when people talk about Barbie games in the modern day, along with most of the titles released before Fashion Designer in 1996, but has a special place in the history of the doll when it comes to gaming.