As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

As one of gaming's oldest and most well-established genres, the humble 'racing game' has undergone several seismic shifts over the decades – which is impressive when you consider the fact that the objective rarely changes from making sure you finish in front of everyone else. Geoff Crammond's thrilling Stunt Car Racer is one such memorable paradigm shift, as is Nintendo's blissfully playable Super Mario Kart. Criterion's Burnout is equally notable, as it introduced a new brand of vehicular combat that offered a much-needed shot in the arm to a genre that was becoming increasingly stale by 2001.

Of course, video game trends are often cyclic in nature, and by the time the decade was drawing to a close, Burnout itself had spawned multiple sequels and its format was arguably feeling a little tired. A desire to try something new spawned not one but two competing racers; Bizarre Creations' Blur and Black Rock Studio's Split/Second, the latter of which is our focus here. Both of these titles aimed to fuse realistic worlds with fantastical elements that would set them apart from previous examples of the genre.

Brighton-based Black Rock – formerly known as Climax Racing before becoming part of the Disney Interactive family in 2006 – had worked on titles such as MotoGP '06, Hot Wheels: Stunt Track Challenge and Pure, the latter of which gained widespread critical acclaim for its tight controls and focus on off-road stunts. The positive response to Pure meant that Black Rock's next project was the subject of intense media scrutiny, setting the stage for what would become the studio's most famous release.

It's perhaps fitting that a game that was aiming to 'out-Burnout' the Burnout series should be created by more than one member of the team that made Criterion's destructive racer so successful. After a decade of working on print video game magazines like ZZAP! 64, Computer & Video Games, MegaTech and Mean Machines, Paul Glancey crossed over to the other side to join publisher Eidos, a move that marked the start of a production career which has also included stints at UbiSoft Reflections and Double Eleven. Glancey was part of the team at Criterion that created the original Burnout and was hired as Franchise Design Director on Split/Second.

He was joined at Black Rock by Steve Uphill, another Burnout veteran, who came on board as Franchise Art Director. "I started in games quite late, with my first game being Microsoft’s Train Simulator, which was being made at Kuju Entertainment," Uphill recalls. "I was at Kuju for a couple of years before joining Criterion as an Environment Artist working on Burnout 2’s Interstate track – this is the first game where Paul and I started working together. After Burnout 2, I worked on all the other Burnout games, working my way up to Art Director on Burnout Revenge and Burnout Paradise. I left Criterion at the end of Paradise and joined Black Rock to work on Split/Second."

While both men weren't there for the actual inception of Split/Second, they agree that the game's genesis comes from the point mentioned in the opening paragraph of this piece – by the close of the 2000s, the racing genre had become rather worn-out. "Racing games weren't selling as well as action games at the time," Glancey explains. "I was told that the concept was for a hybrid action and racing title that would straddle both camps." Uphill concurs. "I think there was a general feeling at the time that the racing genre had become a little stale, which is why I think both Black Rock and Bizarre Creations decided to mix it up, try something different."

Racing games weren't selling as well as action games at the time. I was told that the concept was for a hybrid action and racing title that would straddle both camps

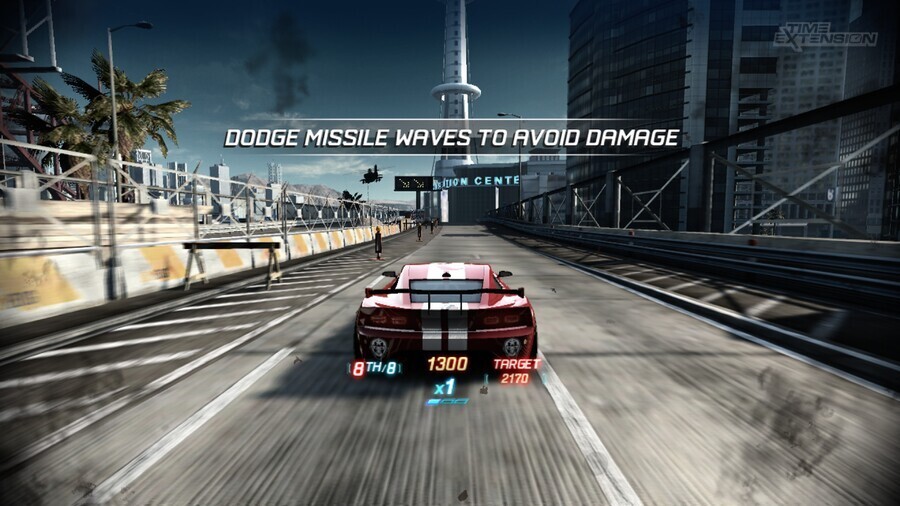

Split/Second was definitely different. While on the surface it looks a lot like its contemporaries, the action was based around triggering various trackside events – known as 'Power Plays' – to your advantage; you could cause explosions that would wipe out your opponents or open up shortcuts to shave a few seconds off your tap time, all of which took place against the backdrop of a fictional television show, lending the pyrotechnic premise a real-world weight. Despite this distinction – and a move away from direct car-to-car combat – Split/Second was almost instantly compared to Burnout when it was announced, something that proved to be both a help and a hindrance in hindsight.

"Burnout is a game, and a team, I’m incredibly proud to have been connected with," Glancey says. "I think Burnout is still the archetypal battle racing franchise, THE game to beat. The original premise of Burnout Revenge was going to be turning up the destruction seen in Burnout 3: Takedown – ripping the cars in half when they crashed and demolishing bits of the world, but we couldn't pull it off in an impressive way at the time. I don't think the promise of 'Burnout Plus Bigger Explosions' would have turned anyone off Split/Second, and I think, as a battle racing game, we came pretty close. The Power Play mechanic was a little less immediate for the player than Burnout's boost system, but that was the game's whole schtick, and it's still impressive even now. Plus, we didn't have Burnout's 60Hz frame rate and sense of speed, but the game was more about control anyway. Racing games are always a balance of Speed vs Control."

"I know that I used a lot of my previous experience on Burnout when I was working on the game but I think that any arcade racer that comes out is going to be compared to Burnout at some point," adds Uphill. "I’ve spoken to folks since making both of them and some feel that they loved what Split/Second brought to the genre. As Paul says, it didn’t have the immediacy of Burnout or the visceral speed, but it more than made up for those with the spectacle of the Power Plays."

Another element of the game that felt unique at the time was the drastically stripped-back HUD; elements such as your speed and how many Power Plays you had stored up were displayed directly below your car. "The big deal about the game was that the action would be more cinematic than any other racing game – Jerry Bruckheimer, Michael Bay-style action exploding all over the screen," Glancey explains. "If we'd covered that up with a regular HUD it would've detracted from the look and feel we were trying to create. Director Nick Baynes talked about having the HUD in the world, in that kind of Augmented Reality way – something which is pretty common today, but back then it was quite novel. Having the Power Play meter and the scores and race position hang behind the car went against some of the conventional wisdom of having everything right up in the player's eye-line, but it seemed to work. I don't think we had the quantity of reward messaging that, say, Burnout 3: Takedown had, so I don't think it was too big an issue."

The big deal about the game was that the action would be more cinematic than any other racing game – Jerry Bruckheimer, Michael Bay-style action exploding all over the screen

For Uphill, the toned-down UI was all about keeping the player's attention focused on the car. "I’d made enough racing games to know that when the action is intense the player only really looks at a very small part of the screen; it’s normally a small area around the car, so I thought it would be interesting to see how much valuable information you could get in that area so the player didn’t have to look elsewhere. It also fitted nicely with the TV show premise of the game. We did a substantial amount of pre-vis for this HUD along with a lot of user testing – it also took a lot of convincing for some folks – but when you played the game it made sense and worked well. It also freed up the rest of the screen to really let the Power Plays shine and brought a more cinematic feel to the game. It would have been safer and easier to take a more conventional approach and stick to the tried-and-tested model of having HUD elements in all four corners of the screen, but it took a special kind of magic and hard work to push the boundaries and innovate here. We also got a patent for it in North America!"

While Split/Second lacked aspects such as Burnout's 'takedown' attacks and refillable boost meter, the aforementioned Power Plays really did add something tangibly unique to the experience – so it's little wonder that both Glancey and Uphill feel they're the strongest element of the game. "Whilst the Power Plays took a huge amount of concept, pre-vis, planning and execution, seeing the final versions in-game was hugely rewarding – even more so when you saw players' reactions to them," says Uphill. "Technically they were a challenge, too; having a moving collision that required the player to either drive on or around it – and still make it fun – was an incredible challenge. The Dam was a prime example of this; I remember this took six months to create from start to finish. The team were incredibly talented and made a real difference; sure, we planned a lot before moving them into production but there were so many happy accidents that the team discovered whilst building them that we could never have imagined or hoped for."

Getting the balance right was hard. "With Split/Second we could have had just a few set-piece Power Plays around each track, so you're constantly waiting for your next opportunity to hit the button," says Glancey. "Then they would have ended up being an annoying distraction from the racing. Or we could have covered the track in a lot of small Power Plays that you see over and over, so they stop feeling special. We could have had a load of small Power Plays plus one or two big ones per level, but then the big ones would have been boring; you can't get excited if the one highlight of the action is the same in every race. So we had to have a large selection of big-money stunts that worked – they could change the race, they looked spectacular and they could play out differently, not always in the same order, and not always with the same result. A skilful player could dodge between the engines on the crashing plane, or barely make it through the closing short-cut route."

Glancey also echoes Uphill's sentiment about the Power Plays being tricky to physically factor into each circuit. "It was an enormous effort. The Power Play geometry had to fit perfectly into the track layout, in all its destruction states. The triggering areas had to be just right – not too close and not too far away. The timing of the animation had to be bang-on as well, so you could drop an air traffic control centre on the driver ahead of you, you could see all that destruction play out, but by the time you got there the dust had to be settling so you could get through unhindered. This took a massive effort from an amazing team of designers, animators, VFX artists and world artists. We had to ship a whole other team of world artists from Europe to Brighton for months to get it all done. It was a herculean effort, over a lot of late nights and weekends, I'm sorry to say."

[The Power Plays] became so difficult and expensive to pull off that they sucked up too many studio resources and knackered the original release schedule, which ultimately knackered the game's success and, I suspect, the studio

Ironically, when quizzed about what element of the game they would change, both former Black Rock staffers give the same answer. "Probably the Power Plays, for most of the reasons already mentioned," replies Glancey. "They became so difficult and expensive to pull off that they sucked up too many studio resources and knackered the original release schedule, which ultimately knackered the game's success and, I suspect, the studio." Uphill feels that, although some incredible work was done in getting the balance spot on, the Power Plays eventually became too predictable. "I wonder if we could have made more of the medium and smaller versions to add more variety to the tracks. I would also have loved to add some randomness to the larger ones, too. They suffered from the 'Seen it once' problem, so having some unpredictability would’ve been nice."

As we've already mentioned, Split/Second found itself in the somewhat unenviable position of launching close to Blur, a thematically-similar racing game that was to be published by Activision. Was there any rivalry between the two teams making these games? "Not so much on the dev team, apart from people being wary of Split/Second hitting at around the same time as Blur – the standard dev team paranoia," replies Glancey. "My friend Charnjit Bansi, who had helped design Burnout Revenge and Burnout Paradise, went to lead the design on Blur, and we ran into each other at E3 and joshingly rubbished each other's games. I think there was an industry event that staged a competition between Charnjit and Nick, where Charnjit had to play Split/Second and Nick played Blur. Bizarre made some amazing games over the years, so I have nothing but respect for that team."

What's perhaps most surprising is that neither Split/Second nor Blur would achieve the kind of commercial success their respective publishers desired, despite gaining glowing reviews. "We came out at a busy and noisy time, which probably didn’t help," replies Uphill when asked why this came to be. "Plus, in my 20+ years of making games, launching any new IP is incredibly tough – let alone in the racing genre, where players know what they like and trying something new is always going to be risky." Glancey cites other reasons for Split/Second's commercial struggles. "The scope of the game meant Split/Second ended up shipping several months later than intended. If we had shipped as originally planned, the game wouldn’t have been as good, so hats off to Disney and the Black Rock bosses for having faith. But the timing made a big difference. Releasing a week before Blur didn’t help us, but then releasing on the same day as Red Dead Redemption didn’t help, either. I don’t think there was an awesome amount of marketing support at the time either, because – and this sounds hokey now, but it’s what we were told at the time – advertising space was at a real premium by the time we were getting to release, it having already been snapped up by sponsors of the 2010 World Cup."

It’s a small industry and I made some great friends and relationships during my time there, and still work with a few folks that made Split/Second

Plans for Split/Second 2 were afoot, and the game's ending even alludes to a sequel, but reports from the time suggest production was closed down at the end of 2010 following a reduction in the number of staff at Black Rock. The following year, Disney Interactive closed the studio completely, making 300 staffers redundant. Both Glancey and Uphill had left the company by this point. "The downside is that a studio closure is no fun for anyone involved," says Glancey, who is now employed as Design Manager at Double Eleven in Guildford. "The upside is that it released a load of talented individuals into the Brighton ecosystem, and they spawned a load of micro-studios, many of which have had massive success – Studio Gobo, Electric Square, Shortround Games... the list goes on." Uphill – who is now back at Criterion Games as Head of Content/Executive Art Director – adds that he's had the pleasure of teaming up with some former colleagues over the years since Black Rock's closure. "It’s a small industry and I made some great friends and relationships during my time there, and still work with a few folks that made Split/Second."

While Split/Second may not have earned enough coin to keep Disney's bean-counters content, it has nonetheless gained a cult following over the past decade and is easily playable on more modern consoles thanks to the fact that the Xbox 360 version is backwards compatible with both the Xbox One and Xbox Series X/S. Could its beloved status mean that we might get that proposed sequel, or, failing that, the remaster treatment? "I do still play it on Xbox, thanks to backwards compatibility," comments Glancey. "I still think it looks great and plays well. Maybe it deserves a sequel, but I don't think a remaster would add much, to be honest. It still impresses me as it is."

Comments 16

A genuinely enjoyable game that holds up very nicely. I'd have interest in a sequel, that's for darned sure.

A new site with a Split/Second feature? You got my bookmark right there.

This game is still great to play to this day. There really hasn't been anything like it. Even the PSP version did a commendable job.

I bought this one fairly recently on 360, really need to spend some more time with it, quite impressed with what I’ve played so far.

This was such a great game! A couple friends of mine and I easily put 100 hours into it in total. Triggering Power Plays was a total talking at the water cooler moment for us, and I always wished for a sequel. Still holds up today.

I'm playing burnout paradise, really brilliant edtion to the franchise or series. I remember playing burnout for gamecube, I must have played it for 2 years before I unlocked the last car a roadster, but it was brilliant when I unlocked it, the car just moved where ever you wanted it to and the speed was like 100mph. No mention of Acclaim, did they have something to do with the series.

awesome game which I'm still playing today thanks to BC. If anyone has Apple Arcade check out Detonation Racing. It's a cell shaded tribute to Split/Second and if you play it with a controller (I play it on 4K screen with an Xbox controller with my Apple TV) it's superb.

This game is a master piece, still playing it on my ps3. So underrated, easily one of the best racers ever. A sequel or remaster should be made. Reading this article proves the immense talent behind this title 👏

£2.24 well spent! That's my weekend plans sorted 😁

Split/Second was the first game I played when I upgraded my TV to a proper 1080P effort way back in 2010. It was such a great visual showcase, I remember playing it and not much else for quite some time.

For me the Burnout series peaked with Burnout 3. I never really liked Burnout Revenge (or Paradise!) all that much for some reason, so Split/Second felt like a spiritual successor to the classic arcadey Burnout series. It was just a refreshing Michael Bay style over-the-top racer which I could play in small chunks without too much messing about upgrading bits and bobs.

Really great feature Damo, it's interesting to learn a bit more about the background of this amazing game. Such a shame that it never got a sequel.

Loved this game. I'll probably never forget the moment where the music fades off, as a hulking great big areoplane comes crashing head on toward you on one of the tracks. Pretty sure I almost soiled myself first time it happened.

Best frigging arcade racing game I've played. I am still looking for a better one even in this generation.

@SuperKMx Detonation Racing on Apple TV could be considered a sequel

@gingerbeardman as I said earlier

@norwichred i used the reply function to let a specific person know

It blew my mind in 2010. Such a powerhouse in graphics (still looking great) and presentation, innovative and fun.

Im not fan of dinamyc soundtracks, but was well made in this game.

I cant understand how can we live a world that games like Split Second doesnt have a sequel (metal gear revengeance is another one)

A sequel from the creators of the first one would be a dream come true.

I love split/second. It's one of the only good racing games left on steam. They've all been delisted, mostly for licensing.

Split/Second is one of my favorite racing games of all time, full stop. It's one of the reasons I still keep the PS3 around hooked up, just in case I feel the need. It's a shame you need to resort to mods/hacks to add the dlc and "fix" controller support on the pc version.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...