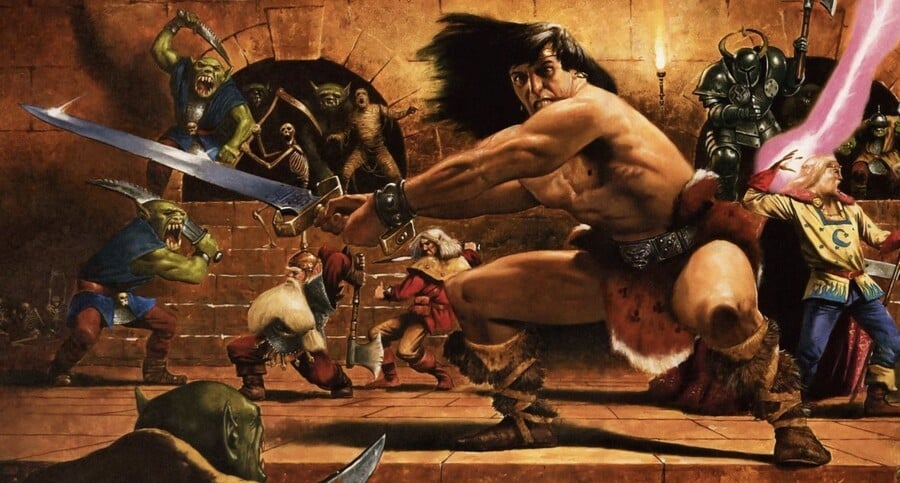

Tabletop gaming is huge these days, but it wasn't always the case. Back in the late '80s, this type of game wasn't exactly mainstream and came with something of a stigma attached; while Advanced Dungeons & Dragons captured the imagination of geeks the world over and Games Workshop's Warhammer line was bubbling under with fantasy fans of a similar disposition, these were very much confined to specialist stores and the wider world was almost oblivious to their charms; compare that to today, where it's possible to pick up some of the most niche tabletop titles in your local high street toy store, and there was clearly some way to go.

One of the games that bridged that gap and served as a gateway drug to the wonderful world of tabletop gaming was Milton Bradley's HeroQuest. Produced in collaboration with British company Games Workshop, it became something of a phenomenon and, incredibly, was sold in mainstream toy retailers like Toys "R" Us alongside the likes of Monopoly and Kerplunk. HeroQuest was tabletop gaming gone mainstream, and its impact cannot be understated.

"I was interested in toy soldiers and model-making from a very early age," says Stephen Baker, the British designer behind HeroQuest. "A lot of my friends would play simply standing soldiers up and then knocking them down using marbles or matchstick firing canon. I would paint my soldiers, and this kind of rough play would chip the paint – so I made up some rules. You got to roll dice depending on whether you had a pistol, sub-machine gun or rifle, and so on. The movement was based on multiples of 6-inches."

At this period in time, tabletop wargaming was still very much rooted in reality – or, to be exact, past realities, rather than in a world of fantasy. "My dad saw a book in the library sometime after called The War Game by Charles Grant," Baker recalls. "He brought it home for me, and I never looked back. That book walked through how Grant developed his rules; it was like reading a game designer guidebook. I fully embraced all his rules and made a switch from primarily World War II to more Napoleonic wargaming. Grant’s later tile, Napoleonic Wargaming, was also a well-read favourite. I still have all those books! The interest in wargaming also led to my interest in terrain and dimensionality. The fantastic photographs in Napoleonic Wargaming feature the figures and expansive terrain of the legendary Peter Gilder. I dreamt of having a wargame table like the ones shown."

Baker's dream and appetite for tabletop wargames would lead him to the London Games Workshop, founded by Ian Livingston and Steve Jackson – who also penned the wildly successful Fighting Fantasy series of "choose your own adventure" game books. This was also the store that would eventually evolve into the Games Workshop juggernaut we know today, the company which presides over the Warhammer and Warhammer 40,000 universes.

"I had a friend who worked at the Games Workshop store at Dalling Road in Hammersmith at the weekends," Baker recalls. "He introduced me to the manager, and I began working Saturdays. I had a full-time job at the time working in a bank just down the road, so I would also pop in at lunchtime when I could. One of the staff then left, and an opportunity came up for me to work full-time at the store. It was maybe a crazy move at the time – quit a steady job with career opportunities at the bank or work as an assistant in a games store; needless to say, I chose to work in the game store! Games were my passion, and that’s what I went with. I did meet Steve and Ian from time to time – both really nice guys."

Baker's job at Games Workshop might have been a case of the heart ruling the head, but it paved the way for bigger things – and a chance encounter opened the door to a much larger company. "A gentleman from Milton Bradley – also known as MB Games – phoned the store as he was looking for some wooden playing pieces," he remembers. "I explained that Games Workshop was not an actual workshop but a games store. We chatted, and I talked a lot about the variety of games we sold. I was asked if I would be interested in play testing some games. Of course, I said yes. I took three days off work and went to MB’s offices in Richmond. I sat in a meeting room for three days and play-tested games, wrote reviews on them and talked through what I thought with the Vice President of Design, Roger Ford. At the end of the three days, they asked if I would be interested in working full-time as a games designer. Of course, I said yes."

With a plum job at one of the world's leading board game manufacturers, Baker was now in the enviable position of being able to exploit his passion for tabletop gaming on the biggest possible stage. He'd already had some experience in creating his own game system. "I ran a role-playing campaign for many years," he tells us. "It was my own system, with elements of AD&D and Rolemaster thrown in. Very early on I described this to colleagues as 'Role-playing in a box.' It needed to have all the trappings of a role-playing game and yet be simple enough for anyone to play."

This would prove to be the genesis of what would become HeroQuest, but convincing a company like Milton Bradley to take a punt on such a niche venture wasn't straightforward; the company was famous for accessibly and family-friendly fare, like Twister, Battleship and Buckaroo. While the company did have some experience in the realm of tabletop wargaming via its 1960s 'American Heritage' series, the notion of publishing a relatively complex tabletop title with overt fantasy elements wasn't an easy sell for the company behind Hungry Hungry Hippos.

As we got more into the development, I worked closely with some of the designers at Games Workshop, particularly on the miniatures

"It took a while," admits Baker. "Roger Ford, the VP of Design, was always very open to new ideas. I provided a summary of the rising interest in fantasy as a genre and fantasy gaming. Not only were there more and more games – both board games and role-playing – but there were also the "choose your own adventure" books, the best known of these being the Fighting Fantasy series by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone." The success of these books, first published in 1982, was compelling evidence that the lucrative children's market was ready for more of the same.

Rather than produce HeroQuest 100% internally, MB Games teamed up with the aforementioned Games Workshop – and its Citadel Miniatures line – to create it. Despite Baker's prior employment with the firm, he wasn't the one who made this collaboration happen. "The two companies were introduced by a third party, and it dovetailed with some of what I had been advocating for internally," he explains. "As we got more into the development, I worked closely with some of the designers at Games Workshop, particularly on the miniatures. These were all sculpted by the very talented Citadel Miniatures team."

It would have been easy for Baker to run away with the concept and create something as complex and nuanced as Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, but he was keenly aware of his audience when it came to designing HeroQuest. "It had to be simple," he says. "This was going to be a game sold in regular mass market stores alongside other family games. It needed to look and feel like something kids could manage to play. In a regular RPG, the Dungeon Master is an experienced player who manages much of the game. The 'DM' in HeroQuest was likely to be just like any other person playing this for the first time. The structure of the game needed to facilitate pick-up-and-play mechanics; this was not going to be a game where the DM had to prepare ahead of time."

Right from the outset, I wanted dimensionality. I wanted the game to have 3D components to match the miniatures

One of the many things that made HeroQuest stand out on store shelves was the exquisitely-designed plastic figures, representing both the four heroes and the many enemies they would face. Baker was keen to have this aspect in place from the start of the project. "Right from the outset, I wanted dimensionality. I wanted the game to have 3D components to match the miniatures," he remembers. These tangible physical elements – which included doors, treasure chests and even furniture – helped to create an immersive experience and aided Baker's overall vision for the game. "I wanted the game to have the narrative feel of a role-playing campaign. The storytelling needed to be simple yet compelling. I wanted the players to feel like they were on a grand adventure."

Getting the balance of HeroQuest right was no mean feat, and Baker admits that fine-tuning it was a challenge. "Early versions of the game were more complex. I play tested with children at a local school, and they struggled with the structure of the game. The original design used floor tiles; these slowed the game down as players had to find the right tile. They could make a mistake and place the wrong tile which would then create problems later in the game. It was also another whole level of explanation I had to provide for the sales and marketing team."

Having hit something of a brick wall, Baker went back to the drawing board – or, to be more precise, gameboard. "I decided I needed to approach things a different way; I worked all weekend and reframed the game to use a standard gameboard. That standard board was actually taken from Axis & Allies, another MB wargame set in World War II. These were larger three-panel boards used in many of the 'Gamemaster' series. That board was eventually cost reduced to a regular two-panel board. However, it retained the essence of how the rooms were laid out. The gameboard was really the central piece of innovation that facilitated the ease of play I was looking for. Games no longer migrated off because of tile placement. No one had to search for tiles. The gameboard allowed players to guess at how the map might unfold. The play area was defined right from the beginning, and it made orientating the quest maps easier."

I decided I needed to approach things a different way; I worked all weekend and reframed the game to use a standard gameboard

Upon its initial UK release in 1989, HeroQuest was a commercial revelation. Baker's streamlined ruleset might not have pleased the series tabletop gamers (Games International's Philip A. Murphy awarded it 3.5 out of 5 stars, saying, "HeroQuest is a good game waiting to be a great one"), but it clearly hit the spot with the more casual audience – an audience which had perhaps never experienced this kind of game before. Thanks to MB's might in the toy industry, HeroQuest would make its way onto store shelves all over the world – not just those found in specialist retailers – and this exposure drove sales rapidly. It could also be said that HeroQuest was the right game at the right time; Games Workshops' business was growing at this point and increased interest in tabletop gaming meant that HeroQuest benefited, especially as it served as the ideal 'gateway drug' into the world of serious wargaming and was heavily and effectively promoted by its manufacturer.

Expansions such as Kellar's Keep and Return of the Witch Lord prolonged HeroQuest's retail lifespan, and a video game from Gremlin Graphics arrived in 1991 to robust critical and commercial success. Games Workshop released Advanced HeroQuest (without MB's involvement), a more complicated version of the game which was sold mainly through Games Workshop's own chain of stores and didn't get the widespread distribution of the original. HeroQuest paved the way for another board game collaboration with Games Workshop in the form of 1990's Space Crusade, set in the same 'grimdark' Warhammer 40,000 universe that the company had created and was inspired, in part, by the Space Hulk board game that Games Workshop produced in 1989. This too was a considerable success and also spawned its own video game adaptation.

A few expansions and updates followed, but the 1994 release of the video game Hero Quest II: Legacy of Sorasil would prove to be the final HeroQuest product for over 25 years (this was also the year that MB Games was purchased by toy giant Hasbro). By 1997 the HeroQuest trademark had lapsed, and it was picked up by the now-defunct game publisher Issaries, Inc., which applied the name to a totally unrelated tabletop role-playing game. In 2013, Moon Design Publications picked up the HeroQuest trademark and, like Issaries, used it for a different game system rather than one which was based on Baker's original. Eventually, the name would return home to MG Games (or Hasbro, to be more precise) in 2020 – and this event also marked the return of the brand to store shelves.

Via its Avalon Hill subsidiary, Hasbro relaunched HeroQuest in 2021. This release was made possible via a crowdfunding campaign via Hasbro's Pulse the previous year, with a target goal of $1,000,000. This goal was met within 24 hours of the campaign going live, securing not just the creation of an updated version of the game but also the similarly updated Kellar's Keep and Return of the Witch Lord expansions. At the time of writing, the HeroQuest line is due to expand again, with The Mage of the Mirror expansion due for release in Spring 2023.

While Hasbro has removed all Games Workshop branding from the new HeroQuest – an understandable move, given how large the British company has become since the early '90s – it was canny enough to involve Baker in the development of the new edition of the game. "The folks at Hasbro were kind enough to ask me to write a bonus Quest Book for the relaunch," he explains. "It was a lot of fun; I had not written a HeroQuest adventure in over 28 years. A lot of people have taken this as an opportunity to buy a fresh version of a game from their childhood and use it to introduce their children to the game. I love the fact that people want to introduce others to a game they have such fond memories and passion for."

Baker left MB Games in 1992, rejoining its parent company Hasbro in 1998. He then worked in a wide range of roles, eventually rising to the position of Senior Director of Product Design and emigrating to the US. In 2019, he left Hasbro to form his own game design business, via which he intends to create new games and IP in addition to providing consultancy on other projects. While he is very much focused on new challenges, he acknowledges the incredible impact of past successes, most notably HeroQuest.

"I will forever be proud of my involvement with HeroQuest," he concludes. "I cannot tell you how many people over the years have thanked me for designing the game. People are very passionate about their stories and memories of playing HeroQuest when they were young. I have heard from many people how it got them into gaming or inspired them to pursue creative careers, whether it was game design, writing or art. One of the biggest thrills I have in being a game designer is to think of all the hours of fun my games have generated over the years. I think of myself quietly as a 'smile maker'. The more smiles, the happier I am."

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.

Comments 6

I have fond memories of playing Heroquest with my son…. Last week!

I found a boxed copy of the game which was only missing a couple of models in a charity shop for £5 about 5 years ago!!

I started playing it with my youngest in lockdown and every few weeks we do an adventure from the quest book. I purchased the GW fellowship of the ring models from my local war games store to use as the heroes and regularly expand the adventures for my son to add in logic puzzles and roleplay story elements and he loves it!

Great read, thank you. The re-release of the latest edition of this rekindled my nostalgia for the original, so I’ve now bought copies of the original game and the 4 main expansions that released in Europe over the past few weeks!

I did think about buying the new version, but I don’t like the models anywhere near as much. It’s probably nostalgia, but I much prefer the simple, almost cartoony look of the original models. Plus Firmirs are way better than those giant fish things in the new version!

I’m hoping my 2 daughters will play the game with me when they’re a bit older. Otherwise it’s just more toys for me!

I’ll probably still buy the new one in the future. I think the US rules are mostly better than the UK rules, especially with monsters’ body points, although searching is more of a faff in the US rules.

I also recently downloaded an Amiga emulator so I can play the Heroquest video game from Gremlin. The music alone is just so nostalgic.

I think I’ll pick this up for the family at Christmas. Great memories and a great introduction to the world of fantasy D&D style games for a new generation

Excellent article thank you! I got this at release here in NZ when i was all of 8 years old and have loved it since. My original copy went the way of the 5200 but i picked up an as new copy with kellers’ keep 8 or so years ago. It is still mint and I still play it now with my son (12). To me it is timeless and a perfect introduction to the world of table-top fantasy gaming.

Well, I just purchased the new edition.

I still have my '90 edition, and it's still a lot of fun to play with friends

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...