Choice is a powerful thing. It's what differentiates video games from other mediums of entertainment. Outside of watching alternative endings on DVD, the outcome of a movie cannot be influenced by the viewer; likewise, a great album's track listing can be randomised, but the songs remain the same. In games, the player is able to directly impact the world with their own actions. This liberating and intoxicating sense of involvement was also central to the appeal of Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone's Fighting Fantasy line of interactive gamebooks, first established in 1982 – ironically, a time when the video game industry appeared to be tiptoeing dangerously close to oblivion.

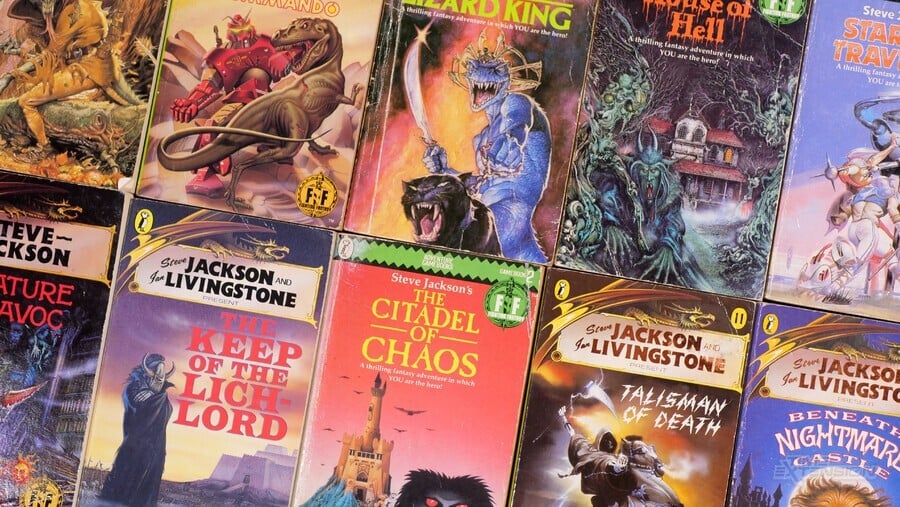

The Fighting Fantasy gamebooks followed a non-linear format; you started at the beginning and ended at the end, but in between, you would flit backwards and forwards through the pages, picking choices at the conclusion of each passage which could either take you to glory (turn to 246) or spell certain doom (your adventure ends here). Confrontation was also inevitable and was decided by throwing dice to resolve combat with the many monsters, aliens and other hostile creatures you faced throughout the 59 original books which were published between 1982 and 1995. Around 15 million copies were sold during that period of time – a figure that creators Jackson and Livingstone could never have possibly expected when they pitched the concept to publisher Penguin in the early 80s.

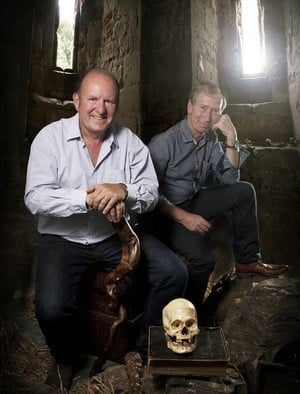

"Ian and I started Games Workshop in 1975," explains Jackson. "At the time, it was an amateur operation, run from a flat in Shepherd's Bush. We published a games fanzine by the name of 'Owl & Weasel', sold obscure games by mail order and manufactured classic wooden games like Backgammon and Go – hence the name 'Games Workshop'. But then we discovered Dungeons & Dragons, and very quickly, everything switched over to role-playing games. We promoted the new hobby and obtained exclusive European rights to D&D and many other RPGs. We published White Dwarf magazine, established a shop and ran the Games Day convention. It was at one of these conventions in 1980 that we met Geraldine Cooke, an editor at Penguin Books. We managed to persuade her to consider publishing a book based on the role-playing hobby."

With a foot in the door, Jackson and Livingstone set to work on their proposed book, but it quickly became apparent that their pitch to Cooke could be improved. "Originally, this book was supposed to be a 'how-to-do-it' manual," continues Jackson. "But when it came to describing how to play RPGs, we came up with the idea of describing a game in action and ultimately decided it would be best done by letting the reader make choices. The more we thought about it, the more we really liked that idea. In fact, it was much more interesting than writing the RPG manual! So we abandoned the manual idea and put together what was to become the first gamebook." Their prospective publisher was rather taken aback by the change of format. "Geraldine didn't know what to make of it at all!" laughs Jackson. "She was expecting a guide to the hobby, but what we proposed was something completely different. She 'considered' the idea for several months before eventually giving us the green light."

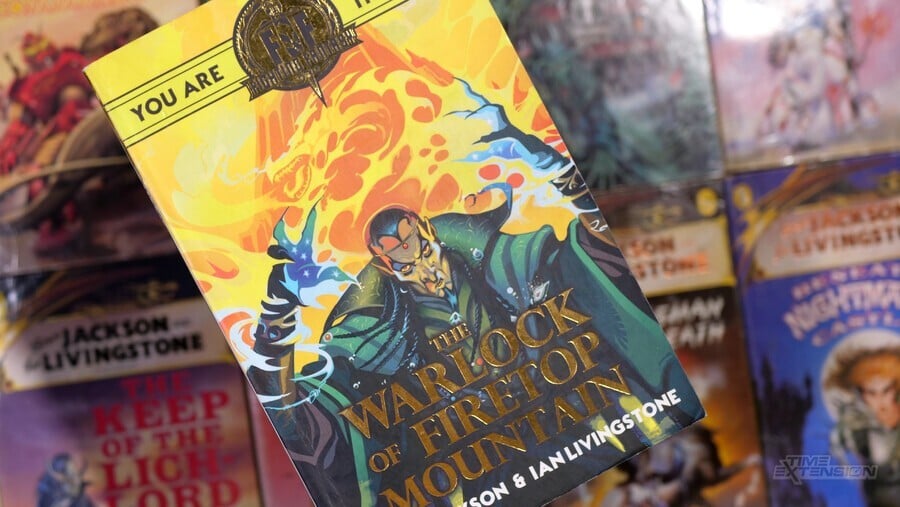

Jackson and Livingstone divided writing duties between themselves for the book – at this point called The Magic Quest but eventually published under the more striking title of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain – and this process created problems almost instantly. "You might notice that The Warlock of Firetop Mountain was co-written, but subsequent titles were written by us individually," Jackson says. "That was because it was a nightmare dividing the Firetop Mountain adventure between us. We had both created different combat systems for our parts of the adventure. Ian's had a 'Strength' factor and mine had 'Stamina'. Both were equally as good, but we had to decide on one of them. At one point, we even decided to play a game of pool for it!

Writing a half-decent book is harder than you might assume – just ask any aspiring author still striving for their first big success – but writing one with a non-sequential story and multiple pathways is a whole other level of demanding. "Inter-meshing all the references was a complex task," explains Jackson. "There was no margin for error, or else you'd maybe get stuck with nowhere to go, like a computer crash. Personally, I always started by writing the background and the start of an adventure, and then switch to writing the end. The last bit to be written was always the middle, so I could 'tune' the whole thing to 400 references."

At the time, it was all a bit of a blur. Warlock was reprinted many times over the first few months. The publisher wanted us to write more – and quickly! 'How about another adventure in...a month's time?'

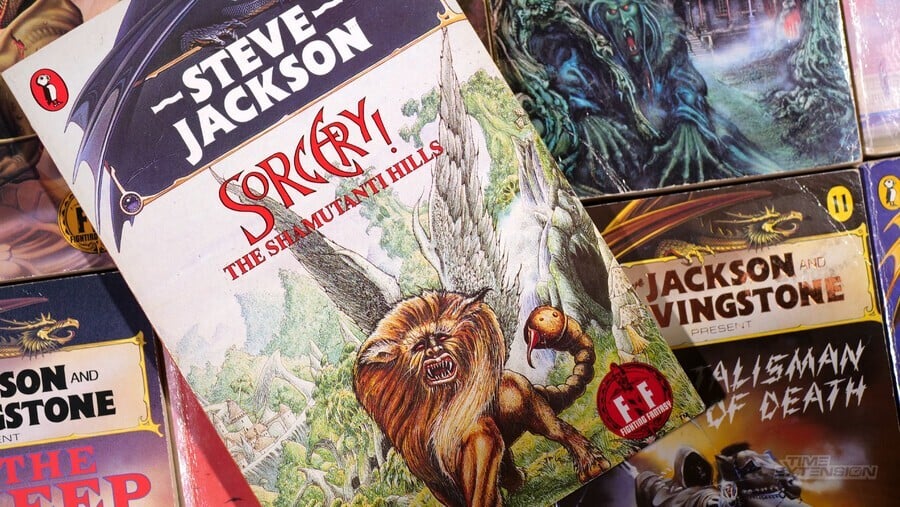

Penguin's Geraldine Cooke may have opened the door for the pair, but she wouldn't get the ultimate credit for launching the series. "Geraldine was an adult editor at Penguin," explains Jackson. "But in the end, they decided that Warlock should be published by Puffin – the children's books arm. This was because they had a Children's Book Club which ran through schools, and sales were likely to be higher. I always felt a bit sorry for Geraldine; she had discovered us but now had nothing to show." Jackson promised Cooke at the time that he would endeavour to create an adult range of similar books, which would eventually become the Sorcery! series, released a year later in '83.

Of course, such a promise would have counted for little if the first Fighting Fantasy novel was a flop, but thankfully that wasn't the case. The Warlock of Firetop Mountain was a runaway success, with demand far outreaching print supply. The incredible events of this period are still hazy to Jackson even today. "At the time, it was all a bit of a blur. Warlock was reprinted many times over the first few months. The publisher wanted us to write more – and quickly! 'How about another adventure in...a month's time?' The Citadel of Chaos – the second book – took about five weeks, after which time I was exhausted. But inspired by the publisher's encouragement and the phenomenal sales figures, there was no time to rest! A typical day was being in the Games Workshop office at 8:30am, working through the day until 7pm, driving home, catching a bite to eat, getting the typewriter out and typing until maybe 1am. Weekends were all for typing. We had zero social life; it was amazing we managed to keep our girlfriends. And still, they wanted more books! So eventually, we came up with a solution: bring in outside authors."

Getting additional help was the only way Jackson and Livingstone could realistically keep the series going, and maintaining momentum was vital in what was becoming a rapidly competitive marketplace. "After the first six to seven books, all the other publishing houses started coming out with their own versions of Fighting Fantasy," Jackson remembers. "We couldn't stop this, so the solution proposed by Puffin was to have a new Fighting Fantasy book every month. So readers going into their bookshops would always have a new Fighting Fantasy book and would hopefully prefer that to one of our competitor's books. As Ian and I couldn't write a book a month, we opened Fighting Fantasy up to new authors. The 'Jackson & Livingstone Presents' series came into being. The first new author was... Steve Jackson!"

After the first six to seven books, all the other publishing houses started coming out with their own versions of Fighting Fantasy

Even to this day, many Fighting Fantasy readers aren't aware that not one but two Steve Jacksons worked on the franchise – the second being the Texas-based founder of Steve Jackson Games. Hiring a namesake wasn't a concerted effort to hide the exhaustion of the core team – this fortuitous arrangement came about thanks to Games Workshop. "It all started when Steve Jackson came to the Games Workshop office to talk about distributing his games in Europe," says the English Steve Jackson. "We finished our business and told him how well Fighting Fantasy was doing but how we needed to sign up more authors. He volunteered himself there and then, and spent the rest of his trip in our boardroom with a typewriter, writing Scorpion Swamp. He finished it off on his return to the US."

While Jackson and Livingstone were comfortable with having other writers on board, they insisted on maintaining ultimate creative control over the series. The original novels largely took place in the fictional kingdom of Allansia, lending the books a feeling of consistency and depth. However, the need for flexibility required the frontiers of this fantasy world to be enlarged somewhat. "When the 'Presents' series started, we were a little worried about keeping track of this 'consistent universe' aspect," explains Jackson. "So we expanded the Fighting Fantasy world from just Allansia to the world of Titan, which comprised three continents: Allansia (where the Jackson and Livingstone books were based), The Old World (where Sorcery! and The Tasks of Tantalon were based) and Khul, where the 'Presents' series of adventures were located."

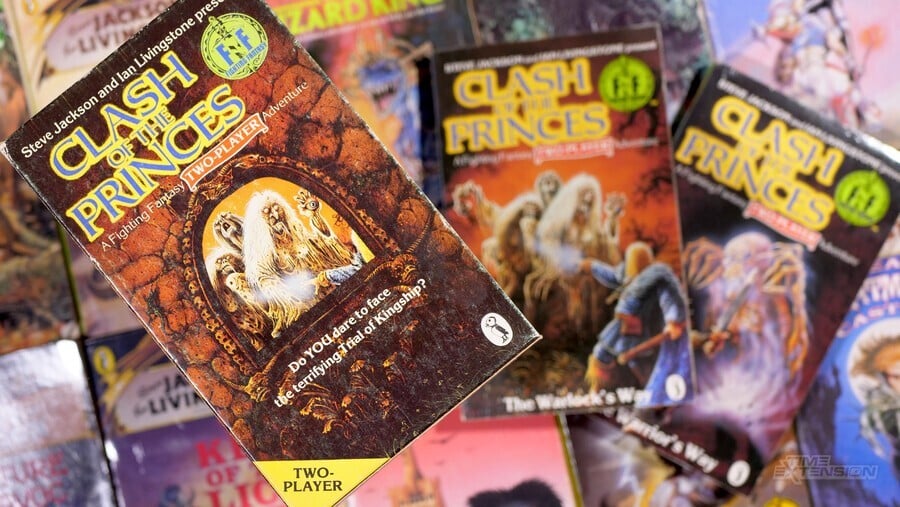

Getting more people involved also allowed the franchise to avoid the one pitfall which could have prematurely ended its success: a lack of fresh ideas. "We didn't want to write 'yet another' dungeon-based adventure; just churning out noble quest after noble quest was going to have the fans turning to other gamebook series," says Jackson. "That's where I think the 'Presents' series came into its own. There was a constant supply of quality adventures, which left Ian and I with the luxury of being able to pick and choose – not needing to churn them out to keep the series going." Possibly the most ambitious gamebook was 1986's Clash of the Princes by Andrew Chapman and Martin Allen, which was a two-book, two-player adventure that could be read along with a friend, both playing a different character. The pair of books were intended to be tackled simultaneously, with each player's experience synchronised with that of the other.

We were really lucky to have contacts with most of the UK's top fantasy artists, mainly through White Dwarf, which was by that point monthly and had a constant appetite for covers and fillers

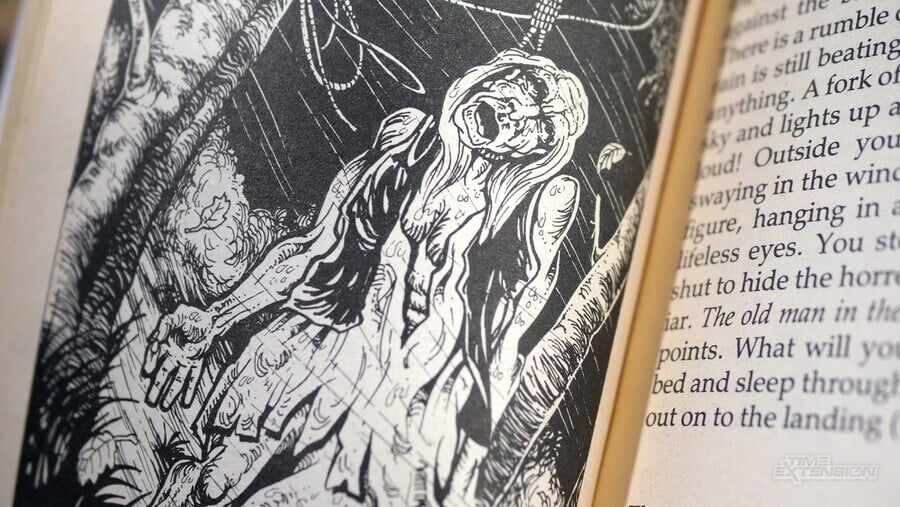

The stories crafted by the new authors were just as compelling and captivating as the early entries, but for many Fighting Fantasy fans, it's the amazing covers and stunning illustrations which provide that nostalgic hook after all these years. Jackson and Livingstone's connection with Games Workshop – and its White Dwarf magazine – allowed them to mine a rich vein of artistic talent which included the likes of Ian Miller, John Blanche, Martin McKenna, Iain McCaig and Russ Nicholson, amongst others. "We were really lucky to have contacts with most of the UK's top fantasy artists, mainly through White Dwarf, which was by that point monthly and had a constant appetite for covers and fillers," remembers Jackson.

Given the often dark nature of some of the books, it's hardly surprising that the original print run wasn't entirely without incident. "There were a couple of adventures that had Puffin – which was, after all, a children's book publisher – feeling nervous," Jackson explains. "In House of Hell, there is a typical black magic ritual scene where a naked girl is being sacrificed on the altar. Tim Sell drew her covered with a sheet, but with a small amount of what might be described as 'nipple' visible. That one had to be re-touched before Puffin would let it go through. And I remember a 'game over' incident in Talisman of Death which describes the reader looking down to see himself impaled on a bloody spear, with his own guts and entrails spewing onto the floor. And, of course, there were always the clashes with religious groups like the Evangelical Alliance, who thought children shouldn't be reading about black magic, demons or the undead."

These groups should have perhaps been more concerned with the fact that Fighting Fantasy was creating a generation of dishonest youngsters. So enthralling and well-written were the novels that many fans – the author of this piece included – blatantly cheated in order to keep the narrative flowing. Fingers would be used as impromptu bookmarks to ensure that wrong turns could quickly be backtracked, and combat situations were never resolved but always won regardless of the strength of the foe. Does Jackson feel short-changed that after all the effort that went into creating these finely-tuned gamebooks, a certain percentage of readers shirked the challenge and cheated?

This is an argument Ian and I have had. He says that since no one uses the combat system legitimately, there is no point in having it – all the stats might put people off

"I think the answer is 100 percent of people cheated!" he laughs. "That's what everyone tells us. Do we mind? No. But to those who cheated death and granted themselves victory in every encounter with a creature: would you have preferred the combat without the Skill and Stamina stats? Perhaps you were just given a choice of whether to 'Come on strong' or 'Hold back and let him make the first move'? No need to roll dice and count down Stamina points? This is an argument Ian and I have had. He says that since no one uses the combat system legitimately, there is no point in having it – all the stats might put people off. My take on it is that coming across a Red Wyvern which is Skill 12, Stamina 24 gives you that small sense of heightened fear – even though, in the end, you'll just ignore the battle and turn to the page where you've defeated the creature. Having the stats in offers the same sort of appeal as, say, Top Trumps."

As the world of Fighting Fantasy grew, so too did the number of associated works and spin-offs. "The popularity of Fighting Fantasy paralleled the spread of RPGs and the many supplements they spawned," Jackson says. "We published Out of the Pit, the equivalent of Dungeon & Dragons' Monster Manual. It sold well, so the obvious follow-ups were other similar sourcebooks – like Titan: The Fighting Fantasy World, Blacksand and The Riddling Reaver – but these were more relevant to people playing RPG campaigns and not really useful at all to the gamebooks, except insofar as general background material. I wrote Fighting Fantasy - The Introductory Role-Playing Game. This was a very simplified version of Dungeon & Dragons. More recently, Graham Bottley of Arion Games has written a proper RPG rules system – Advanced Fighting Fantasy – and he is reprinting the original sourcebooks."

Fighting Fantasy was one of the many properties to be impacted by the rise of interactive entertainment in the early '90s, yet it has endured. Jonathan Green's Curse of the Mummy – which was published in 1995 – would be the final original entry until the release of Bloodbones in 2006, but since then, the franchise has continued to expand. "I am always amazed at the fact that, in spite of the PC and console revolution which has seen drastic reductions in board game sales, Fighting Fantasy soldiers on," says Jackson. "Apart from three years during the transition from Puffin to current publisher Wizard, Fighting Fantasy is still around – and in France, they've never been out of print." The 2002 purchase by Wizard Books (the children's imprint of UK publisher Icon) resulted in several new instalments, including Blood of the Zombies, the Fighting Fantasy book which would mark the 30th anniversary of the series in 2012.

I changed the world to modern day, but didn't go the whole hog and have the adventure set in shopping malls - I opted for a castle to keep some link to my fantasy roots

"I'd forgotten just how much fun it is writing a Fighting Fantasy gamebook," says Livingstone. "Luring readers to their doom in false hope, knowing that gruesome death awaits them makes me smile when I'm writing a gamebook. When I got down to writing Blood of the Zombies, I naturally thought about setting it in Allansia. Except for Freeway Fighter, all my books were medieval fantasy. However, I was well aware of video gamers' everlasting love of zombies, and I also knew that I had never given them their rightful place in a Fighting Fantasy book. The more I thought about zombies, the more I thought they were best placed in the modern world, especially since it's more fun to use shotguns and the like against them."

Blood of the Zombies marked a significant tonal shift for the franchise. "I changed the world to modern day, but didn't go the whole hog and have the adventure set in shopping malls - I opted for a castle to keep some link to my fantasy roots," explains Livingstone. "Most video gamers like exciting, fluid action without too much interruption. I decided to streamline the combat system to allow a fast-paced dash through the book with quick, exciting battles mowing down huge swathes of zombies with a variety of guns and grenades. Skill and luck were dropped and replaced with a new attribute – damage."

The rights to the series were acquired by Scholastic in 2017, which has gone on to publish new titles and reissue many of the original books, all with brand-new artwork. "Scholastic are the world’s largest publishers of children’s books, so we were thrilled when they made us an offer we couldn’t refuse," says Jackson. "But there were some teething problems at the start, particularly in the art style. We were used to ‘High Fantasy’ art – a la Dungeons & Dragons and Lord of the Rings – but Scholastic’s plan was to appeal to younger children by dumbing down the art. We didn’t like it, but more importantly, the fans didn’t like it. Things have changed a bit since then."

Scholastic are the world’s largest publishers of children’s books, so we were thrilled when they made us an offer we couldn’t refuse, but there were some teething problems at the start

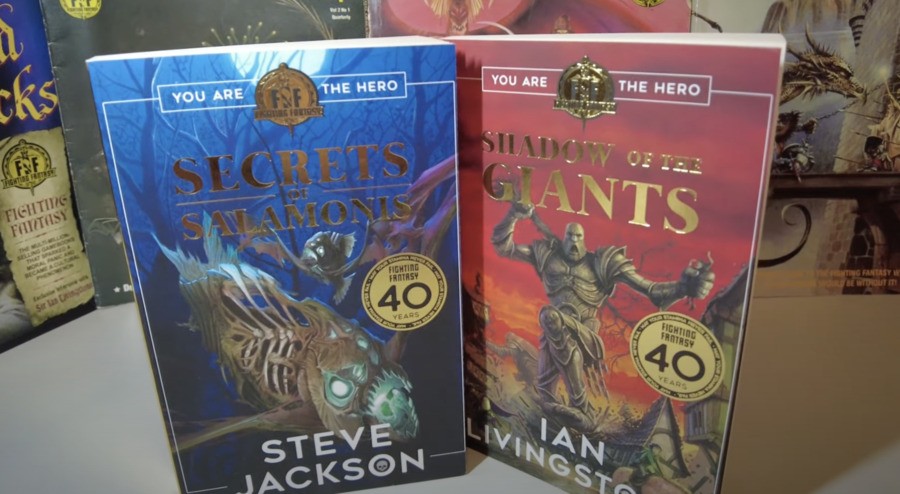

Just as he'd done for Blood of the Zombies, Livingstone was tempted to return to the series for this revival, penning Shadow of the Giants (Jackson also wrote another book, Secrets Of Salamonis, which launched at the same time). However, he was faced with something of a quandary. "Children who enjoyed Fighting Fantasy books back in the 1980s now have their own children and are passing the baton," he says. "Children usually reject out-of-hand anything that their parents suggest might be cool or fun, but I’m pleased to say that Fighting Fantasy resonates with Generation Z in much the same way as it did with previous generations because of its interactive format. But nonetheless, writing Shadow of the Giants caused me a dilemma. Should I write it for 10-year-olds or for 45-year-olds masquerading as 10-year-olds? In the end, I did what I always had done – I wrote it for myself and hoped it would appeal to fans young and old."

Interestingly, Livingstone reveals that the creative process for writing a new Fighting Fantasy book hasn't changed a great deal, technology aside. "I still write them the same way as I did, except for using a computer to input the narrative instead of using my old fountain pen and ink. But the format is the same, creating an annotated flow chart as I go and manually numbering 400 paragraphs. The structure is the same. I begin by thinking about the objective of the quest, where the adventure is going to take place, the main protagonists, and the overarching storyline."

"The writing itself is an iterative process, not least because you’re dealing with several branches of the story at once," Livingstone adds. "There’s a lot of back and forth. You realise that you need a key at some point, so I have to find a place to put one somewhere earlier in the adventure where people would find it – or not! The main challenge is making sure that all the branches interact logically. You don’t want people to get stuck in a loop, but you do want them to arrive at certain pinch points for the sake of the story, and for certain information you want them to have. Another consideration is gameplay balancing, so that it’s not too hard or too easy. And you have to make sure the economy is balanced so there are not too many or too few gold coins. Last, but not least, you have to ensure that the story is compelling and enjoyable."

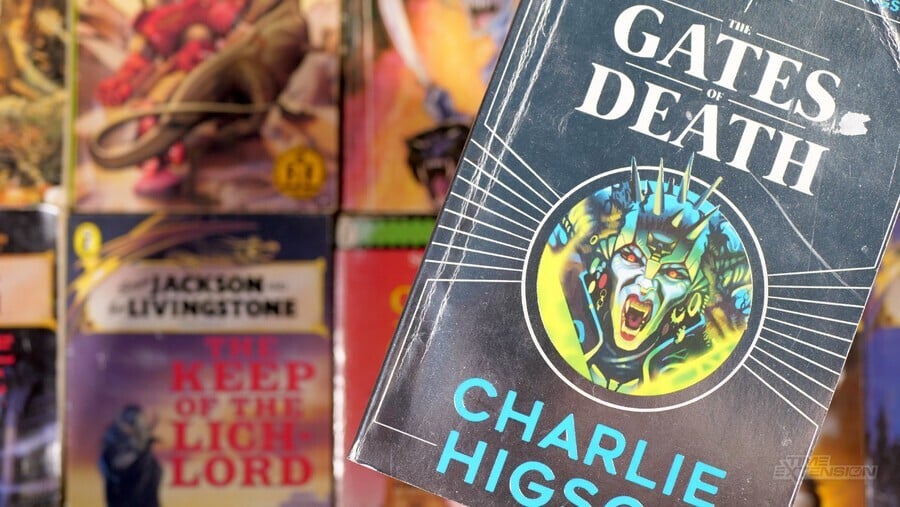

For two of the other more recent books, Livingstone and Jackson employed the talents of Rhianna Pratchett – daughter of Discworld creator Terry and a video game writer who has worked on Heavenly Sword (2007), Mirror's Edge (2008) and Tomb Raider (2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015) – and Charlie Higson, who rose to fame as part of the British sketch comedy The Fast Show but has since become arguably more prolific in the realm of young adult fiction, penning both the 'Young Bond' books and the post-apocalyptic 'Enemy' series.

I even got into trouble with my local library for keeping one for so long that they actually sent out a letter threatening to take me to court or some such nonsense

"I loved the books as a kid," says Pratchett, who penned 2020's Crystal of Storms. "In fact, I even got into trouble with my local library for keeping one for so long that they actually sent out a letter threatening to take me to court or some such nonsense. I was eight. Thankfully my book-based life of crime was short-lived, and I found it under my bed. I was possibly using it to give the monsters something to do."

Higson – who wrote 2018's Gates of Death – was a fan of the Fighting Fantasy franchise long before he came to work on it, although, as he's a little older than Pratchett, he wasn't the target audience at the time. "I was very aware of the books when they first came out in the early '80s, because they were everywhere. I saw kids reading them on buses and trains and the like, and they were in all the shops, rows of them on the shelves. A beautiful set. I could see that this was a 'new thing'. A cult. I’d always been into fantasy and games, and I was really intrigued. I was slightly too old to be the target readership, but I was interested enough to buy a couple to check them out – City of Thieves and Deathtrap Dungeon were the first two. I could instantly see why they were so popular. They were made with great love and care and attention to detail – the design was great, the illustrations were fabulous, and the game mechanic worked well. The stories drew you in as well, and the worlds were vivid and properly thought through. I kept the books, and when my own kids were old enough, in the late '90s, we read them and played them together."

Higson then followed the careers of the two creators from afar, before a chance encounter gave him the opportunity to contribute. "I saw how Ian had become a big cheese in the computer gaming world," he recounts. "I eventually met him at a gaming event, and we got on well and became sort of friends. I'd always been interested in gaming, whether it was board gaming, the likes of the Fighting Fantasy books, arcade games and then home consoles – Nintendo and Sega. Ian asked me quite early on if I’d have any interest in maybe wring a Fighting Fantasy book one day, which I thought was a really interesting idea."

I went round to Ian's house, and he showed me his insanely complicated diagrams and flow charts that he made for structuring and writing the books. And I realised his brain works very differently to mine

For Pratchett, the route in was via the aforementioned Jonathan Green, a long-time collaborator of Livingstone and Jackson who is still involved with the series to this very day. "I pitched them the idea, but after that, I mostly dealt with Jonathan as my editor, who has written a host of adventure books himself," she remembers. "He'd do playthroughs and juggle the stats for me. I talked a little with Ian about the various ways he used to keep track of the branching and flow in the books. He does a lot of stuff by hand. He told me it was very hard. He was right! That was probably the most challenging part, and I tried multiple systems to try to keep track of everything and eventually used an amalgamation of several different ones."

While the creators of the series have had 40 years to hone their techniques, Pratchett and Higson were relative newcomers to the process – and learning the ropes was perhaps more demanding than they initially anticipated. "I had to pitch all my ideas to them for approval, but once I was up and running, they let me get on with it," says Higson. "Before I started, though, I went round to Ian's house, and he showed me his insanely complicated diagrams and flow charts that he made for structuring and writing the books. And I realised his brain works very differently to mine. I knew I couldn't get involved in a process as complex as his. So, I kind of had to navigate my own way through and figure out a system that worked for me. The one thing that I took away was the idea of pinch points. You can't have a story that is endlessly splitting; the books would be massive, so you have to build in the illusion of a completely interactive branching storyline. So you create three or four points in the books where all the converging stories meet up, consolidate and then start again. That was very useful."

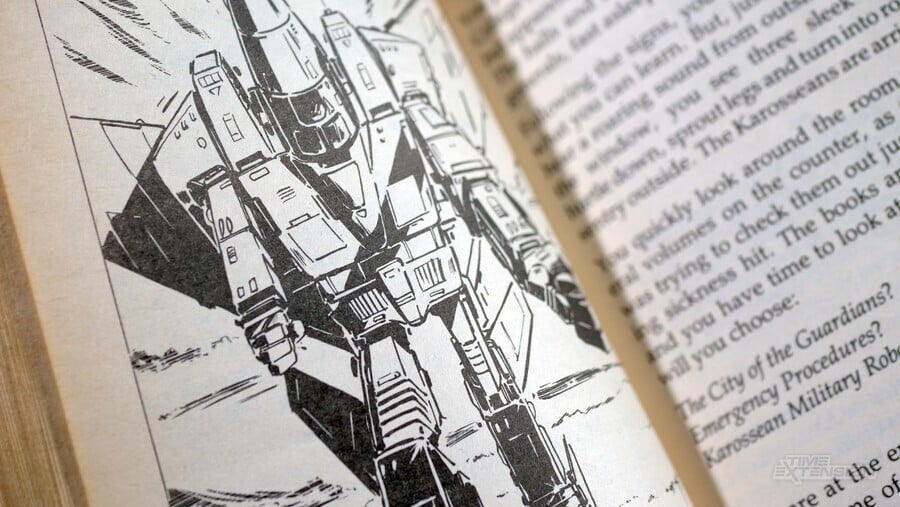

Higson reveals that it soon became very clear to him that writing a linear narrative is a world away from dreaming up a branching story which lends the reader a degree of agency. "Halfway through the book I got absolutely stuck," he reveals. "I was in a room with a crazed drunken troll and there was no way out. I had to do a massive amount of backtracking and redesigning. I discovered that the biggest problem in writing one of these books is that the book cannot update itself in the way that a computer game can. So, for instance, in a computer game, if you hit the troll with an axe and kill him and then go away on an adventure and come back later, he'll still be dead. If you want to have the option to return to a location in the book – say to pick up something you missed – or take a different route which might lead you back to this point – you have to build in quite a complicated mechanic so that you don’t find the troll somehow alive again, with no memory of ever having met you before. I wanted to get a lot of story and character into the book and not have it filled up with endless variations of the same scenario, and a lot of plodding mechanics, just so the thing worked properly. Getting the balance between gameplay and the other elements was pretty tricky."

Higson says working on the series has helped him develop his talents further as an author. "I actually found it really useful as a way of thinking about storytelling, and it shook up my creative process. It was fascinating and illuminating and made me think about the idea of branching stories, of evolving stories, of stories that can change every time you read them. It really opened up my mind, and some of the lessons I learned I've used in writing that I've done since. I’ve also done a few sessions in schools where I’ve used ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ techniques as a way of helping kids to learn something about writing and storytelling. One really important concept is that the character in the story (or the reader) has to make a significant choice in every moment, which then influences everything that comes after."

Pratchett says she's keen to create another game book in the future, and muses on precisely why this series continues to find an audience. "There's a special connection between a book and its reader. And with Fighting Fantasy, the tactile nature of turning the pages back and forth, writing down the stats... this forges a kind of uniquely engaging bond. Plus, books can survive being dropped in the bath pretty well."

Indeed, it's fascinating to note that the arrival of consoles, handhelds, computers, tablets and smartphones hasn't entirely killed off the humble gamebook. "It's interesting that what killed Fighting Fantasy books off almost overnight in the 1990s was home computers and home gaming," says Higson. "Kids could enter these worlds and have these adventures without having to do the complex business of wielding pencil and eraser and working out combat statistics. But now it’s kids’ familiarity with computer gaming that might lead them to these books, as teachers can say 'Oh, you love computer gaming, this book is a bit like that.' Also, of course, the kids that became obsessed by these books when they first came out now have kids of their own and want to share something of their youth with them. The original books were so well made that they still hold up very well today, and they’ve influenced so much of computer gaming that these worlds are very familiar to modern kids. Also, there were enough kids who got so absolutely obsessed with these books that they now really enjoy creating new ones of their own. But in the end, you know what, they’re fun."

The original books were so well made that they still hold up very well today, and they’ve influenced so much of computer gaming that these worlds are very familiar to modern kids

What's even more interesting is that Fighting Fantasy has a solid track record of embracing digital media as a means of expanding its already considerable reach. "In the early days, the attempts to bring Fighting Fantasy to the small screen were, in my opinion, uninspired," comments Jackson. "Most simply took the illustrations and the text and put them on the screen. The combat was automatic and obligatory, cheating was impossible...I couldn't understand why someone would spend £15 to read the adventure on-screen – and in low-res at that – when they could buy the book for £3. But more recently, with the advent of smartphone apps, the conversions have been truly great interpretations. Big Blue Bubble raised the bar with their early iOS apps and Tin Man Games have put in an incredible amount of quality design; their apps are masterpieces. Inkle Studios took a big risk – now proven very successful – with revising the combat, spell system and navigation in the Sorcery! series." That particular adaptation recently made it to Nintendo Switch, to marked critical acclaim.

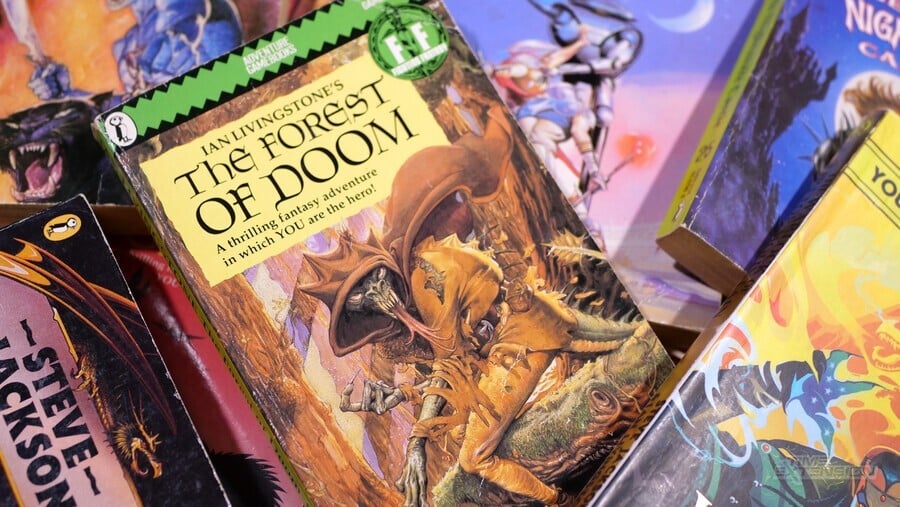

With Fighting Fantasy now 40 years old, it's tempting to ask its creators which of the books they love the most. "I don’t have an absolute favourite since it’s a bit like asking me which of my four children is my favourite!" replies Livingstone. "So, let’s go with four favourite books. Naturally, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain has to be included because it was the first book in the series and the one I wrote with Steve. My other three favourites are City of Thieves, Deathtrap Dungeon and Forest of Doom."

Although every author would like their work to achieve immortal status, few gain the kind of popularity that echoes across four entire decades. Jackson admits that both himself and Livingstone struggle to fully comprehend the magnitude of their success, even today. "We are blown away when we think back to the old days," he says. "We never dreamed that 'The Magic Quest' would still be around 40 years on. Many people currently working in the games industry tell us it was Fighting Fantasy that put them on their career track. I've taught an MA course in Game Design at Brunel University, and I'm always amazed that the students all know and have played Fighting Fantasy, though they weren't even born when the series was in its prime."

What's equally amazing is that Fighting Fantasy has evolved into something more than just a series of books, and Livingstone is keen to support peripheral elements – such as art books and live events – as much as he's able. "I’m writing a lavishly illustrated book with Jonathan Green entitled Magic Realms about the art and the artists who gave Fighting Fantasy its identity and visual appeal. It will be published in 2024 by Unbound, who published Dice Men, the book I wrote about the origin story of Games Workshop. There are two Fighting Fantasy board games currently in development, and a co-op card game entitled Fighting Fantasy Adventures designed by Martin Wallace, who is one of the most successful and respected games designers in the industry. There are also two audio-visual projects being worked on, but more news about that in due course. 2024 is the 40th anniversary of Deathtrap Dungeon, and I’m hoping to have a new gamebook out in time for Fighting Fantasy Fest 5."

Jackson is equally keen to keep the legend alive, although he admits that the passage of time does alarm him. "Last time I speculated about new books was 1989, and the book was The Trolltooth Wars: A Fighting Fantasy Novel. At my age, I’m supposed to retire! But if a good idea pops up…"

This article was originally published on Eurogamer and has been republished here in a considerably expanded format with kind permission.