Few aspects of Nintendo's history are as fascinating to us as the Nintendo Satellaview. Nintendo R&D2 designed the Japanese-exclusive Super Nintendo add-on back in the mid-'90s, with the device allowing users to download video games and other services via a satellite connection.

It came about as the result of Nintendo's investment in a Japanese broadcasting company called St Giga (or the Satellite Digital Audio Broadcasting Corporation, to give it its proper name) and was home to new games in the F-Zero, The Legend of Zelda, and Super Mario series, as well as titles from third-party developers like Squaresoft, ASCII, and Chunsoft. However, today it is a part of Nintendo's history that the famous company rarely, if ever, acknowledges, with most of its library completely inaccessible without the help of emulation and a dedicated community of preservationists who have been intent on rescuing and documenting different parts of its service for future generations.

Misinformation about the device is still rife (thanks in no small part to the information about it only being available in Japan), so we at Time Extension recently set out to find out as much as we could about it. Over the last year, we went combing through newspaper archives and enlisted the help of the Japanese-to-English translator Stephen Meyerink to access never-before-translated interviews. What follows is a more complete history of its service, Nintendo's plans for the device, and why it ultimately ended.

To understand the story of the Satellaview better, though, we first have to take a closer look at St.Giga, and how Nintendo initially became involved with the broadcaster.

The Origin Of Satellaview

In 1990, the owners of the Japanese satellite television company WOWOW decided to expand into the world of satellite radio and created the subsidiary St.Giga. St.Giga was the world's first digital broadcast station and had at its helm a visionary individual named Hiroshi Yokoi. Yokoi had previously made a name for himself in radio at another Japanese station called J-Wave, which was popular in the 1980s due to its increased focus on music over DJs and personalities. However, with St. Giga, Yokoi wanted to take things a step further. Rather than broadcasting commercial music to a set schedule, he wanted St.Giga to transmit ambient sounds to match the tide and time of day.

How this worked, as documented in an article from the Sydney Morning Herald, was that the broadcaster had divided the day up into four segments, including the Sunrise zone, Waterline zone, Sunset zone, and Starline zone. Each of these would feature a different collection of sounds, with the music also changing in intensity based on the day's tidal charts. It was a radical concept for the time and soon became the company's calling card, garnering overseas press such as a radio special called 'Echoes' broadcasted on Philadelphia's WHYY-FM in 1992.

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, this new station was entirely free for its first year, but in March 1991, the service started charging a subscription in order for listeners to tune in.

It was under this new payment model that the company planned to support itself, though, it soon racked up a sizable amount of debt as it struggled to convince the Japanese public, who were living through a recession at the time, to pay for the costly subscription fee and the necessary equipment including an antenna and tuner. By 1993, the company had reported a total loss of $43.1 million and had only managed to attract 40,000 subscribers despite being available throughout the entirety of Japan. It needed investment and new ideas fast, but luckily there was a company that was ready to put up some cash.

In January 1993, the video game company Nintendo paid $6.7 million to acquire a 19.5 percent interest in Satellite Digital Audio Broadcasting Co, and became St.Giga's largest shareholder. It dispatched a management team to help restructure the struggling broadcaster and soon came up with an idea for an innovative new collaboration that would take advantage of its Super Nintendo console.

As various publications reported at the time, including the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Billboard, and GameFan, the two companies announced they were collaborating on a new adapter/cassette package for the Super Nintendo under the name Satellaview. Satellaview would be a satellite peripheral that connected to the bottom of your Super Nintendo and let players download video game software to their consoles via St.Giga radio broadcasts distributed through a subchannel.

Nintendo hoped that this would turn the company's fortunes around and finally make it profitable, with Billboard reporting in 1994 that Nintendo's then-president Hiroshi Yamauchi expected the company to sell 2 million adaptor/cassette packages a year. That's in spite of these sets only being available via mail order and payment for the service not being handled as you might expect.

You see, contrary to popular belief, the product didn't require a subscription to access any of the games being transmitted, with the broadcasts themselves being unscrambled and paid for through advertising and sponsorships. Instead, all you needed was to gather the right equipment in order to receive the signal. This included the base unit that expanded the Super Famicom with an extra 1 MB of ROM space and an added 512 kB of RAM; the custom four-way AC adapter and AV selector, the BS Tuner and antennae; and two distinct cartridges.

The first of these cartridges, labelled BS-X: Sore wa Namae o Nusumareta Machi no Monogatari (commonly translated to BS-X: The Town Whose Name Was Stolen), slotted directly into the Super Nintendo machine. The second, meanwhile, was a smaller 8MBit memory pack that fitted inside the BS-X cartridge and could be constantly overwritten with new games and data broadcasted through the service. What's especially interesting about BS-X is that it not only served as a user interface of sorts, but as an interactive story.

BS-X: The Town Whose Name Was Stolen

How it worked is that upon loading the cartridge for the first time, you would select a name and gender, before being set free to explore an EarthBound-Esque town where you could talk to NPCs and take part in a mystery where you tried to recover its stolen name. Players could enter many of the town's various buildings, with different buildings allowing you to download different types of media (such as games, photos, and news) and purchase items.

Some of the town's buildings included a large temple where players could access data transmitted as part of the Super Famicom Happy Hour, a special three-hour programming block featuring personalities and special Soundlink games (games expanded with voice actors and high-quality music); a museum where users could access older video games; a dedicated event space (which also occasionally hosted Soundlink games); and an idol house where they could obtain images and information about the latest stars.

There was even (controversially) a school where users could download photographs of adult women wearing kogals (essentially clothes designed to look like Japanese school uniforms).

The player's home, meanwhile, was used to manage the data saved to the 8MBit cart. Upon entering, there were four options available to pick from. You could load an existing game file saved to the memory pack, delete the data from the memory pack, erase the current player data, or schedule to receive a future broadcast.

The author and radio producer Yusuke Akamatsu was responsible for writing BS-X's story and gave an insight into his narrative approach during an interview inside a copy of Satellaview Tsushin, from May 1995.

Speaking about why this additional story was included, Akamatsu responded, "It would be a waste to use the BS-X system for only the 3-hour spans of broadcasting, wouldn't it? You don't go to Disneyland to ride one single roller coaster, after all. That's the idea behind this."

Players advanced BS-X's story through conversations with the various weird and wonderful NPCs found hanging around the town. Some of these included a fortune teller, a wannabe idol, and a group of TV-headed children enchanted by a mad professor. As Akamatsu told the magazine, David Lynch's Twin Peaks was a big influence on the overall tone, with the writer hoping to emulate some of that show's success in Japan.

Asked whether it was difficult to construct a story exclusively through dialogue, Akamatsu commented, "Not especially. It was easier than I expected. That said, it was somewhat difficult in that to some extent, the characters and buildings and what have you were limited from the outset. I do find myself thinking I should have included certain other elements now, though."

In the same interview, he expressed some hopes for how the Satellaview service might eventually develop in the future. "Unlike a normal RPG, it has no combat, though it does include most of the other elements you'd expect from one," Akamatsu said. "Right now there's only one background music track, and you can only go to the city, but after the summer we should be able to change the music, show photos via magazines, and develop it into something closer to a full-fledged RPG. In this particular story, the player's powers of imagination and expression are more important than growth via combat. I'd like the content to question players in that capacity."

Akamatsu had big plans for how this mystery would develop, but as Japanese players have told Western Satellaview historians including LuigiBlood, the story was never given a proper ending and was eventually rebooted a few years into the service.

BS-Zelda and Other Games

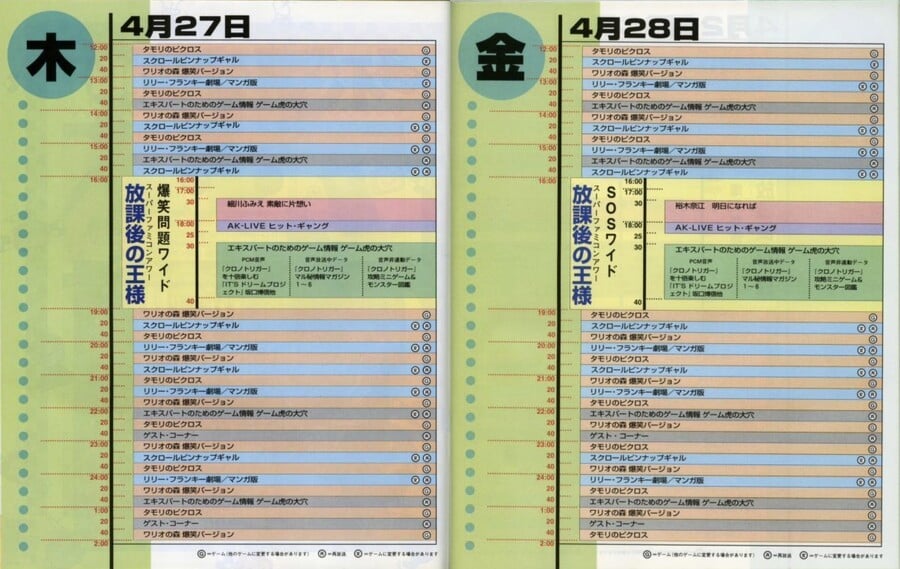

New broadcasts would happen regularly as part of the Satellaview service with players being able to tune into one of St.Giga's satellites and download games and other services based on a schedule. These games were mainly divided into two distinct categories, including regular broadcasts and Soundlink titles.

The regular broadcasts would be downloaded directly to the 8MBit memory pack, whereas Soundlink titles were stored on the pack but meant to be played along with with a live studio broadcast that wasn't archived with the rest of the data. As a result, preserving games for the Satellaview today is typically comprised of hunting down memory packs to find lost games and searching for high-quality video from the time to try and catalog and potentially restore these Soundlinke recordings to emulate the real experience.

Some of the most notable games that were released for the Satellaview include BS Zelda no Densetsu, a 16-bit Soundlink-enhanced reimagining of the first The Legend of Zelda with the BS-X protagonist taking the place of Link; BS Zelda no Densetsu: Inishie no Sekiban, a similar take on A Link To The Past; and Zelda no Densetsu: Kamigami no Triforce, a straightforward port of the Japanese version of A Link To The Past. There were also multiple F-Zero games, such as F-Zero Grand Prix and F-Zero Grand Prix 2, as well as a sequel to Super Mario Bros. 2 called BS Super Mario USA. As for third-party content, Squaresoft also contributed games like Dynami Tracer, Radical Dreamers, Treasure Conflix, and Koi Wa Balance; ASCII delivered games like the horse-riding sim Derby Stallion 96; and Chunsoft contributed the Mystery Dungeon spin-off BS Fūrai no Shiren: Surara wo Sukue.

Shigeru Miyamoto said about the device in an interview with Satellaview Tsushin from May 1995: "It's my hope that when customers buy a Satellaview, they don't think of it as hardware—but rather, an empty cartridge. I can't say at this point how many years the hardware will continue in its current form, but for the time being, it will continue to receive more and more software. It's a little like buying a lucky grab bag in early March (laughs). If customers can think of it as having bought a lucky grab bag for 18,000 yen, Nintendo will continue to make the contents of that bag more and more satisfying for them (laughs)."

Elsewhere in the interview, he also stated: "If a customer purchases a Satellaview unit, they can exchange what's on there as many times as they like without any further cost. There is some cost on the side of the broadcasting station, but it doesn't cost the customer anything further to play. As an example—in the past, there might have been a game that looked like fun to someone, but it was priced at 9800 yen. It's a little tough to say if the game looks like 9800 yen worth of fun. In a case like this, if you buy the Satellaview hardware, you've essentially also bought the software up-front. I think that's a very customer-friendly setup."

From this conversation, we can see that Miyamoto not only viewed the Satellaview service at the time as a bargain for potential customers, but he also believed that it was an opportunity to get around the expense of cartridge-based distribution and a chance to utilize Nintendo's wealth of existing assets to create new experiences for a significantly reduced cost.

He told Satellaview-Tsushin, "Over the course of the next six months or so, things will probably center around games that suit the current state of the platform and games that we ourselves at Nintendo make available. I think if we can figure out how to make it happen, there will be a great variety of software released. We're already well-positioned to create new software for the Super Famicom with relative ease, so by leveraging those current assets to support Satellaview, we'll also be able to come up with some fun things for it."

"In that sense, we're not relying on others [Translation Note: likely third parties, although Satellaview did eventually have lots of third-party support], but I still have high hopes. That's why we at [Nintendo] have to sell lots of good products. Satellaview offers us the possibility to distribute content for free that might otherwise be difficult to sell. Something like that would incur a high cost if we were to try to sell it on the current cartridge standard, but if we only had to send the data, distribution becomes much more doable. The question really is how much of that kind of content we can produce moving forward."

Nintendo's support for the Satellaview was significant over the years the service was running, but, unfortunately, the partnership between the video game company and the radio broadcaster didn't last. Despite the impressive library of games and unique user interface, Satellaview never managed to completely turn around St. Giga's fortunes. As a result, tensions between Nintendo and St.Giga started to develop, with the latter company refusing its investor's help.

The Bitter Breakup

This all came to a head in August 1998 when Nintendo announced that it was cancelling plans to supply video games to St. Giga in the future and that it had withdrawn from an agreement with other companies such as electronics manufacturer Kyocera Corp to further invest in the broadcaster.

The cause for this was that St. Giga had failed to apply for a government digital satellite broadcasting license and had refused to approve Nintendo's plan to reduce the firm's capital to wipe out its accumulated debts. At the time, Nintendo had been planning to supply video games over a new BS4-II digital satellite, due to be launched in 2000, but abandoned its plans after an ex-CEO of St. Giga rallied shareholders against the investor's reforms.

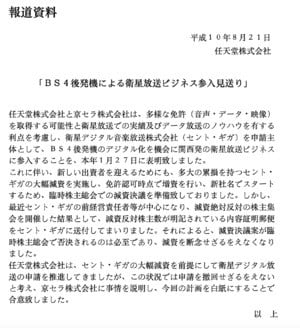

Nintendo issued the following statement on its Japanese website on August 21st 1998, which explained the events surrounding the decision:

"On January 27, Nintendo Co. Ltd. and Kyocera Co. Ltd announced that with the shift to newer-generation digital BS4-II, they would be entering into the satellite broadcasting business. This was done after the companies took into account the advantages presented in being able to acquire a variety of media licenses (for music, data, video, etc), as well as (the primary applicant) Satellite Digital Music Broadcasting Co (St. Giga)'s track record and acumen in the field of satellite broadcasting.

"Due to this move, in order to call for new investors, they planned to implement a large-scale capital reduction in St. Giga (which has a large amount of accumulated losses), and then carry out a capital increase after licensure and start under a new company name. Thus, there was an extraordinary general meeting of shareholders wherein a resolution for the capital reduction was prepared."

"However, the result of a general shareholders meeting held in staunch opposition to the move with a previous CEO of St. Giga at its center was that a content-certified letter was sent to St. Giga, stating the number of shareholders opposed to a capital reduction.

"Accordingly, as it was inevitable that the capital-reduction plan would be rejected at an extraordinary general meeting of shareholders [due to the large number of shareholders opposed], they were forced to abandon the capital-reduction effort.

"Nintendo Co. Ltd. had been pushing forward with the application for satellite digital broadcasting premised upon a substantial capital reduction in St. Giga, but given the situation they believe that they must withdraw the application and have explained the situation to Kyocera, causing the two parties to agree mutually to scrap the current plan."

The fallout from this is what led to the end of Nintendo and St. Giga's relationship. In March 1999, Nintendo stopped providing new content to St. Giga, so, as a result, the broadcaster was forced to continue distributing old programs. The service finally ended on June 30th, 2000, with St. Giga eventually merging with the radio station provider WireBee a few years later in 2003.

In the years following, interest in the Nintendo Satellaview has only grown, with new generations of Western players becoming fascinated by this obscure piece of Nintendo's history, while preservationists race to track down new memory packs to dump, and modders try to replicate different parts of the service and translate them for international audiences.

As for official rereleases of Satellaview games, there's been only a few notable examples. Square Enix's Chrono Cross: The Radical Dreamers packaged the formerly exclusive text adventure/visual novel Radical Dreamers along with a remaster of the PlayStation 1 title Chrono Cross; story episodes from the Satellaview-exclusive BS Fire Emblem were later ported to the Nintendo DS as part of the Mystery of the Emblem remake Fire Emblem: New Mystery of the Emblem; and some other Satellaview games including Sutte Hakkun later got a full retail release for the Super Famicom too (thanks @ChronoMoogle for this additional info).

We'd love to see more Satellaview games get a wider release in the future, but unfortunately, it doesn't seem like Nintendo or other companies will follow suit anytime soon, with the only way to access the majority of the Satellaview's library being through emulation and the hard work of enthusiasts.

Thanks to VGC's Andy Robinson for supplying some of the photos in this feature.