Can you believe that Hudson, which at one time challenged Nintendo with its own console format and did well, now no longer exists? A mere 35 years after the launch of its PC Engine (co-developed with NEC), the name Hudson is absorbed and hidden within Konami.

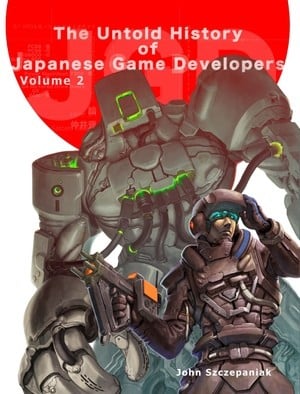

As a fan not just of the system but Hudson in general, I made a point of tracking down as many associated game developers as I could find when researching for The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. I ended up interviewing so many that Volume 2 ended up having a distinctly PC Engine flavour, even down to the cover.

The second volume's cover was painted by Satoshi Nakai, the artist behind Cybernator and Gynoug, and features a 'PC Engine Golum' creature; note its head, chest, and arm. The solder meanwhile carries a gun based on the PC Engine GT.

To celebrate the 35th anniversary, below are excerpts of PC Engine-related interviews from all three volumes, including a personal diary entry on my expedition to the abandoned Hudson building on the outskirts of Sapporo, Hokkaido.

Visiting Hokkaido, Home of Hudson

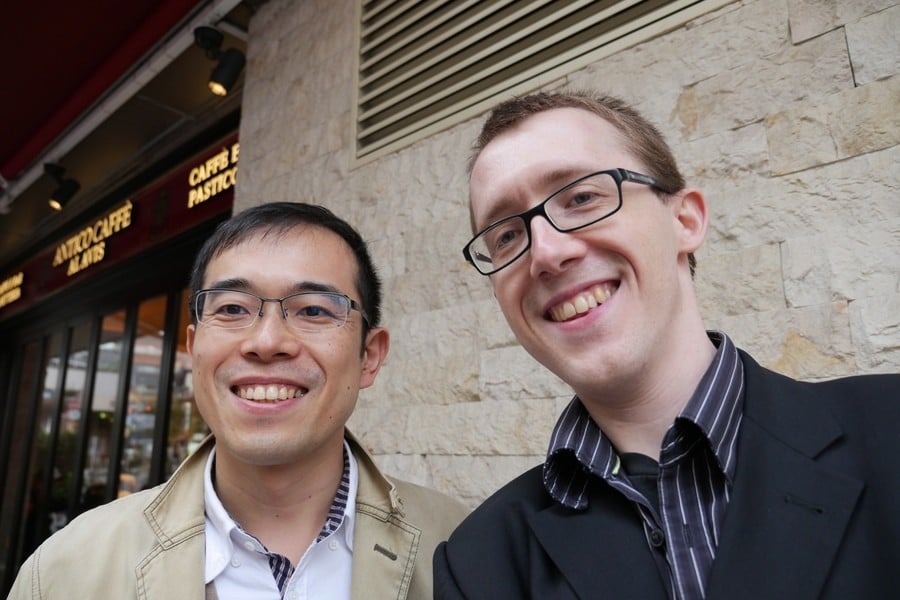

It's 4am. There is never a good way to deal with such an early rise, but I wanted to visit the northern island of Hokkaido, and I had been invited to interview programmers Takaki Kobayashi and Keita Abe. They were involved with Agenda, a company hired by Hudson to produce games for the PC Engine.

I also visited the abandoned Hudson Laboratory on the outskirts of Sapporo. It was recommended by my Hokkaido guide, Matthew Fitsko, who sent me links to the realtor website offering it for lease. We caught a bus and then walked through the woods to find the lab, lonely and hidden amidst hills and pinewood. The perimeter was marked by yellow tape, warning outsiders not to cross.

I crossed the yellow line, wandered around, and pressed up against the office windows, noting an empty sticky-tape dispenser with what appeared to be some former staff's name on the front. What looked like a trashed floppy drive lay in a waste paper basket. There were some filing cabinets, but the labels were too far away to read. I took hi-res shots with my camera, then used the zoom function on the display, hoping to read, "Unreleased Games Be Yonder!" The labels read: "Timing Charts" and "Office Supplies". Boo.

There were no magical discoveries, just lots of overgrown foliage. It was a poignant reminder of how fragile the games industry is. At one time NEC and Hudson led the vanguard for the CD medium in games and produced a multitude of hardware variations, such as the PC Engine, its CD add-on, several varieties of combined systems, US variations, a handheld PCE, plus later the PC-FX. In Japan, the PC Engine held a strong position, second only to Nintendo's Famicom and Super Famicom.

The cataclysmic fall for Hudson, later to be absorbed and forgotten within Konami is tragic, and it can happen to any company. Before leaving the lab to attend the interviews in Sapporo, I noticed two gentleman by an upper-floor window, eyeing me suspiciously as I took photographs. I suggested to my compatriots that we reveal ourselves to be foreign investors wanting to lease the property, so as to get a tour inside. Unfortunately, the buses had a schedule to keep, and so did we. Onwards!

Keita Abe and Takaki Kobayashi of Agenda

These two were hilarious to interview. For the PC Engine, they really only worked on Crest of Wolf, Prince of Persia, and World Heroes 2, but their dealings with Hudson reveal a fascinating world of sub-licensed politics. Also, pants – the conversation was also about pants...

"Crest of Wolf was a sort-of semi-remake," explains Keita Abe, when discussing this scrolling brawler, known as Riot Zone outside Japan. "Because there was an original arcade version, but we changed some of the characters and stages. At that time Westone's arcade game was only available in the Osaka area, so I went all the way to Osaka just to see it being played. We borrowed the PCB, and programmed the game from scratch while playing the arcade version for reference. The development was subcontracted to us from Hudson. Since Hudson created the graphics for us, and since we did not have direct contact with Red Company, I don't know the details regarding Red's involvement. Westone dealt directly with Hudson; I only went once to Osaka to greet Mr Nishizawa."

"At Agenda I manipulated the graphics data, to squeeze it all down, consolidate it," adds Takaki Kobayashi, making compressing motions with his hands and sound effects with his voice. "I made this tool, Tsumetsume-kun, to compress it to something that would fit on the CD. The first time I did this was for Prince of Persia on PC Engine. I had to put the player character, the prince, into these little boxes of 128 pixels by 128 pixels. <intense laughter> So the turban was also kind of the pants! We just reversed the pants and used that!"

(NB: based on our understanding, Kobayashi was referring to the sprite tables which represented graphics data, and given the uniform plain colouring they simply re-used certain sprite tiles - but it's official, Prince of Persia on PC Engine has you running around with pants on your head...)

The topic of Prince of Persia is interesting, since it was not published by Hudson, but rather Riverhillsoft. "Actually that was done by Agenda and Hudson," laughs Abe, sharing a secret few knew. "But probably Hudson wanted to show the name Riverhillsoft, just to show that many software houses were involved. But didn't mention Agenda."

As we ascertained, Hudson was developing lots of games by sub-contracting through places like Agenda. Hudson would fund development and then would negotiate with other companies, like Riverhillsoft, for the sale and promotion. So it would appear multiple companies were developing for and publishing on the PC Engine, thus encouraging other companies to join them.

It all seems like heavily orchestrated chicanery, so we run things by Abe to make sure we understand correctly. "Yes, exactly!" exclaims Abe, nodding. "So Hudson didn't want the consumers to think that Hudson was the only company, and rather many companies were making games for it. So it would appear to be a major thing."

Makoto Goto on Shubibinman 2

Keen-eyed readers may recognise Makoto Goto as the Japanese developer who asked Phil Fish that infamous question. His recollections of the PC Engine describe a close-knit era where small groups of friends could create not just an indie game, but a fully-fledged physical release that was published internationally.

"I worked on Shubibinman 2," begins Goto, using the Japanese name for Shockman on the Turbo-Grafx 16. "This was my first job and used only assembly language. When I was a student at the prep-school for university, I needed to earn money through part-time jobs. I was looking for a job and found this programming job making Shubibinman 2. For the first time I met Toshirou Tsuchida (Front Mission) and also Satoshi Nakai (Cybernator). I met them and was allowed to join the team, working on the shooting stages - for those, all the programming was done by me. Plus some of the AI for the boss characters, some stages, and a lot of characters. I made the AI programming for quite a few smaller characters, the zako or little enemies. Plus I worked on the level designs with the game's designer and artist, Tomoharo Saitou (Streets of Rage 2). There was only four or five people? A very small team."

Interestingly, Goto's resume also mentions an unnamed "character action-RPG" for PC Engine, from 1992. "This was going to be an RPG using a character from a certain famous action game," says Goto cryptically, unwilling or unable to reveal which licensed characters it used. "I joined the project partway through as an event system programmer. However, the project was cancelled several months later. I was very disappointed."

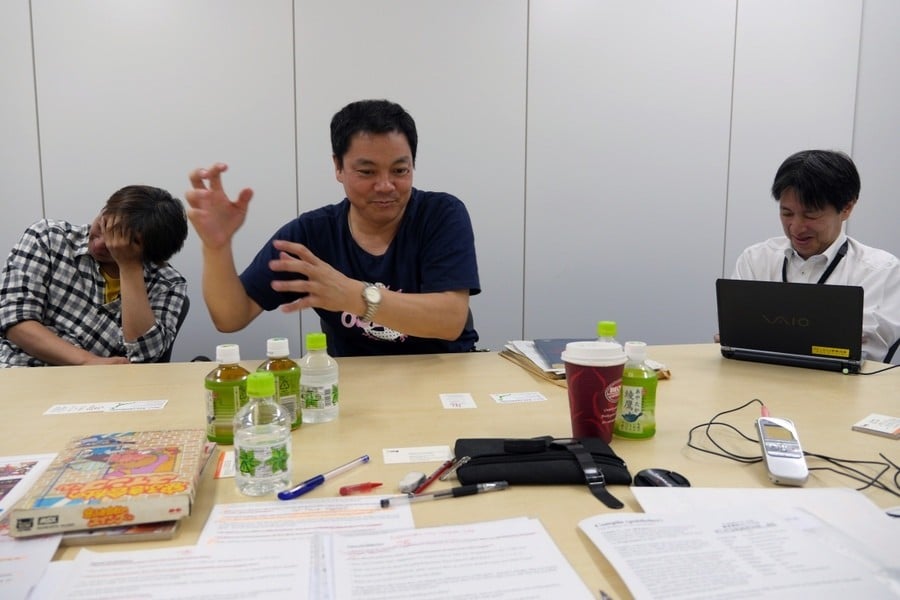

Takayuki Hirono on Gunhed

Part of an interview that lasted over 7 hours (for Volume 3), Takayuki Hirono was a programmer at Compile and helped define the Aleste series. But he also programmed Gunhed, regarded as one of the finest PC Engine shooters, known as Blazing Lazers outside Japan. The intensely passionate monologue below started after a colleague asked him if the sampling sound effects in Devil Crash and Gunhed came about after seeing Shubibinman. We've left his reply as unedited as we could...

"The PC Engine was weak with sound," exclaims Hirono with a passion that captivated everyone in the room. "When you see the audio wave pattern, the sound was not reproduced in the way you wanted it. Also the noise sounded lighter, so with the PC Engine, compared to the Famicom, you could only make a sound like: ka-shew! With Famicom, you could have a wide range of sounds, ranging from explosions sounding like pshu to really low zooming sounds. But with PC Engine you could only have this very light kind of pash-pash-pash! sound. So it was very difficult to express the sound of explosions. But then I came to learn about the sampling method, so I thought I could incorporate sounds that are deep, resounding, explosive sounds, like DRA-GRU-GRU-GRAAH!"

"To give you an example," inhales Hirono, breathless at his earlier gesticulations, "of how light the audio effects on PC Engine sounded, if you recall the level in Gunhed where you're bursting the bubbles, Area 8, it only makes this light kind of psh-psh sound. And that's all you can do with the PC Engine. <laughs> With sampling it really broadened the range of ways to express certain things. With PC Engine it was a lot faster in terms of processing speed, so once you incorporated the sampling method, and as long as you know how to use it, you are able to come up with a broader range of audio expressions. So from that point on, Compile used a lot of sampling!"

"Also! Let me add some comments for the sake of protecting the honour of Hudson," Hirono demands. We let him, without question. "With the PC Engine, the sound has a particular pattern to it. If you don't know how to use the hardware, you can only get one pattern of sound, but if you really know how to use it, then you can produce some very good sounds. I was saying earlier that comparatively the sound was not as good, but if you <intense> really know how to use it, then you can produce decent sounds! So if you knew what you were doing, you could come up with rich audio. You really had to do research and learn how to use these machines."

Hiromasa Iwasaki on defining the CD-ROM standard

"My mother and father told me that I should stop this crazy thing and I should keep studying to be a dentist," reveals Iwasaki when discussing his entry into game development. "They said, keep computers as your hobby. <laughs> But I didn't want to do that. I wanted to be a creator of games."

It's conceivable that had Mr and Mrs Iwasaki had their way, the entire world of video games would be different today. For you see, their son Hiromasa was one of the key figures in defining and refining the CD-ROM format. First for Philips and Sony, as part of a team being consulted when the format was first being conceived. Then later again when Hudson wanted to adopt CD-ROM for the PC Engine.

Iwasaki went into great technical detail on how he pushed for specific styles of data allocation on CD, to reduce seek times and make games faster and more playable. We've removed the jargon, but we're sure you'll agree Iwasaki is something of an unsung hero during this evolution into optical storage.

"I know why Hudson took me on. Perhaps you know the name, Hudson's Shinichi Nakamoto? (Bomberman) He was impressed with my knowledge of CD-ROM. Hudson in 1987 wanted to make CD-ROM games. I gave a presentation to Hudson's people and then afterwards Nakamoto-san asked me... <changes stance; formal business>

"Ahh, hello Iwasaki-san. What other jobs do you have?"

And I said to him, "Do you know about CD-ROM? <smiles, leaning forward> Do you know CD-ROM? I have been working on making a CD-ROM authoring system, and now that I know CD-i is not suitable for games I want to change jobs."

Suddenly Nakamoto-san says to me <intense voice change>, "DO YOU KNOW?! <laughs> DO YOU KNOW CD-ROM?!"

<reverts to normal Iwasaki voice> Yes, I do.

<back to intense Nakamoto voice> "I WANT TO MAKE CD-ROM GAMES FOR PC ENGINE! You have to join Hudson!"

After joining Iwasaki would be involved in several PC Engine CD-ROM games, but his most famous outside Japan is probably Ys: Book I & II. Within Japan, though it would be Tengai Makyou II on PCE CD, a high-profile JRPG which cost 500 hundred million yen in 1992, making it the most expensive video game at the time.

"It was a really big project," admits Iwasaki. "I have to say that Tengai Makyou II was perhaps also the first triple-A title on CD. I believe so, anyway. At that time, we used... <takes pen, writes 500,000,000> In yen. But remember, this is from around 1990 to 1992! <laughs> It was a crazy amount. We used over 20 programmers and also over 30 artists. Hudson and NEC were planning the Super CD-ROM from early 1990. Tengai Makyou II was designed for the Super CD-ROM's functionality - which had four times more RAM - so it was given a really big budget."

Takashi Takebe of Hudson

Takashi Takebe was the 7th employee Hudson ever hired. As a programmer and later producer, he witnessed the company rise from churning out computer shovelware to striving for quality, making connections with the ZX Spectrum, becoming one of the first Nintendo third-party developers, and eventually launching its own hardware. He was a foundational member of Hudson and had seen it all over the years.

Would you believe we only got to interview Takashi Takebe because Takaki Kobayashi, after numerous sake the night before, suddenly recalled a legendary colleague he had to introduce us to? The Hokkaido trip was full of surprises.

One of the first things we showed Takebe was photos of our recent trip to the abandoned Hudson Laboratory.

"Oh! You went there?" says Takebe, astonished that a bunch of foreigners from Europe would travel to a remote abandoned building on the island of Hokkaido. "When was that built… It was right when I was transferred from Tokyo back to Sapporo, so 1993? It's quite an impressive building, isn't it? We thought upper management had lost their minds. <laughs> Originally the name was the 'Hudson Central Research Institute'. It wasn't for game development, but things like development tools, and hardware development. Hudson is an interesting company, because we weren't just developing games, but also creating development tools, GPS navigation systems, and also hardware such as the graphics chips used in the PC Engine. We were making games of course, but Hudson also dabbled in other areas, such as assembly line systems for factories, portable computing terminals for the East Japan Railway Company, LCD watches, and game-pads. I believe Hudson may have been the first company to use integrated circuit cards for a game console, with the HuCards for the PC Engine."

As expected, given his long career at Hudson, Takebe had numerous fascinating revelations to share. One particular highlight was regarding the fabled unreleased Bonk RPG, part of the PC Genjin series of caveman platformers.

"PC Genjin was a pun based off of the name of NEC and Hudson's joint game console, the PC Engine," explains Takebe. "PC Engine led to PC Genjin, meaning a primitive man, which was the basis of the caveman motif. All of the characters had a caveman style to them. The characters were actually designed by Red Company, who handled the planning and design of the titles. The PC Genjin games were action titles. Back in those days, there was a magazine called PC Engine Monthly, which ran a column by Red Company. They ran mocked-up pictures of a role-playing game titled RPC Genjin as a joke, but it got a big enough response that they decided to put it into production. But since it had just been an idea off the top of someone's head, it didn't really develop into anything, and the truth is that the project collapsed without any real development occurring."

For decades there has been speculation about this unreleased RPG, and we now know the truth. It was simply a joke.

Hudson may be gone, but our love for the PC Engine has endured, which is why over 30 years later fans still clamour for a game which never existed. Why Konami chose to release a PC Engine Mini, and in all the major territories. It's why you're reading this article now, because this dinky little system, smaller than a bag of Skips, was something special to be celebrated and remembered.

We'll see you again at the 40th-anniversary party.