Final Fantasy IX celebrated its 25th anniversary earlier this year, having originally released in Japan on July 7th, 2000.

Developed as the last mainline entry on the original PlayStation, the critically acclaimed turn-based RPG proved to be a landmark title in the legendary series, taking the series back to its medieval roots to pay tribute to what had come before.

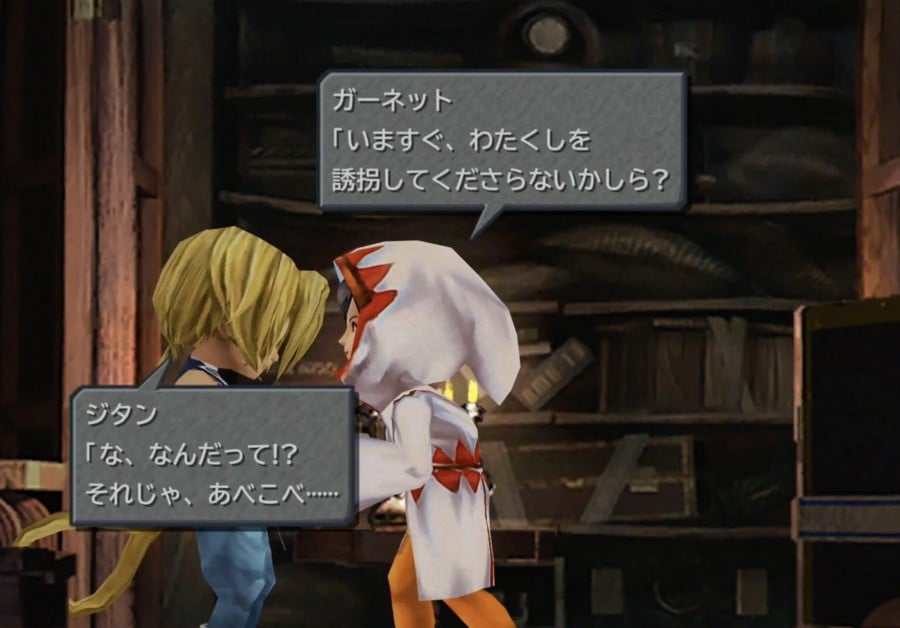

The story of the game memorably focused on the adventures of a thief named Zidane, who kidnaps a princess, amidst the outbreak of war, and soon finds himself teaming up with a ragtag group (including the quick-to-anger knight Steiner, the Black mage Vivi, and the princess herself) to put a stop to an evil Queen and a mysterious figure known as Kuja.

Of course, like many reading this, I didn't personally experience Final Fantasy IX when it was first released in Japan, but instead had to wait for the Western localization to be released later that same year. This localization was handled internally at Square, and was, unlike some other attempts in the series's past and is a fairly remarkable translation of the original text, retaining a lot of the same character and humour from the Japanese version, despite inevitably having to make several changes and alterations to solve problems that cropped up during the localization process.

As a result, to mark the game turning 25 this year, I reached out to Brody Phillips, one of a very small group of people tasked with translating the classic RPG into English, to ask him some questions about his approach to localising the game. He told us more about how he originally became involved in the project, shared some behind the scenes stories about his approach to the game's characters, and gave us some thoughts on whether or not he'd like to see his work being reused, if that mythical remaster that everybody seems to be speculating about is ever released.

You can read our conversation below:

Time Extension: How did you originally begin working at Square localizing its games? Was Legend of Mana the first title you worked on at the studio?

Phillips: Yeah, so after about seven years in Japan, I came back to the U.S.—that’s where I grew up—and started working as a bilingual game tester at Crave Entertainment. Not long after that, I noticed Squaresoft had an opening for a Japanese-to-English translator. I had done some translation in other contexts before, so that gave me a leg up in the interview and on the written test.

Legend of Mana ended up being my first title there. It was classic Square at the time—branching storylines, tons of NPC dialogue, lots of text. I split the workload with another translator, and then our drafts went to a pair of editors who polished everything.

What was interesting about RPGs back then was how the text was structured. The files were tied directly to in-game locations because that’s what got loaded into memory when a player entered an area. At the time, consoles had pretty strict memory limits, so the game would only load the dialogue and other assets needed for that specific place. That setup basically forced us to divide the translation by location rather than, say, by character or chronological order. It wasn’t the most natural way to organize translation work, but it was the reality of how the code and memory worked back then.

Time Extension: How did you get the job on Final Fantasy IX? And how did that compare to working on Mana?

Phillips: If I remember right, I was rolled onto FFIX pretty quickly after Mana wrapped. It was a much bigger game, so this time we had three translators instead of two. That meant coordination became even more important—keeping terminology straight, making sure each character had a consistent voice no matter who was translating them.

Unlike Mana, FFIX had a rotating party system, so you’d have different combinations of characters talking to each other at any given time. That put a lot more pressure on us to nail their personalities consistently across the board.

Time Extension: You’re credited on the game alongside Maki Yamane and Ryosuke Taketomi. How did you divide the work, and what was your specific role?

Phillips: Ryosuke was the lead translator. The three of us divvied up the work more or less by volume—measured in kilobytes of text for each location, menus, that kind of thing. On the editing side, Richard Amtower was the lead editor, and he’s the one who really unified our voices so the whole thing felt seamless.

As for me, I leaned on some of my own interests. I’d studied drama, so for the Tantalus troupe I tried to give their stagecraft a slightly Elizabethan flair. I’d also been dabbling in Scots, so I used that as inspiration for the dwarven village’s dialect. Our whole goal was to capture the sheer variety and texture that was in the Japanese script, but in a way that sounded like it was written in English to begin with—not like it was “translated.”

Time Extension: Do you recall much about how character names were handled? Were you given much freedom to change things? For example, Amarant is called Salamander in the original Japanese.

Phillips: Yeah, that one’s a good example. The philosophy we followed was: try to recreate the emotional effect the Japanese audience got. So in Japanese, “Salamander” sounded exotic and tough—it fit. But in English, a salamander is this small, delicate animal. It just didn’t match the look or feel of the character. So we went with Amarant instead, something that felt harder, more fitting for him.

Time Extension: Most of the characters in FFIX seems to have unique personal pronouns that they use in Japanese, or other dialogue quirks that help to establish their specific personalities. What was the most challenging character to translate into English in your opinion? And why?

Phillips: That’s a great question. The thing is, Japanese gives you a much wider spectrum of ways to build character voice than English does. Just by looking at word choices or grammar, you can often tell whether a character is male or female, young or old, polite or rough. In novels, Japanese dialogue practically tags itself, whereas in English you usually need to rely more on context or descriptive narration.

On top of that, English tends to get standardized in writing—we’ve got things like 'proper' spelling and the Chicago Manual of Style pushing toward consistency. Regional dialects, for instance, often get flattened out unless you go out of your way to signal them. In Japanese, though, dialects can be transcribed with a lot more fidelity, so the quirks really pop off the page.

So the hardest characters to translate were the ones whose voices in Japanese depended heavily on those built-in markers—because we had to find ways to make them distinctive in English without going overboard or making them sound like caricatures. It was always a balancing act: staying true to the intent while making it feel natural in English.

When it comes to challenging characterizations, one I remember the most was Quina. Quina belongs to the Qu tribe, a race of oddball gourmands obsessed with eating and tasting every creature they encounter. In Japanese, Quina’s lines often end with ある instead of だ or です, which is a stereotypical way Chinese speakers are portrayed in manga. To capture that in English, we went with a rough, simplified grammar that has a slightly pidgin feel—enough to make Quina sound different without being too hard to read. Another tricky part was gender. The developers’ notes made it clear that the Qu don’t have genders, and in Japanese the other characters refer to Quina with あいつ, which is a neutral pronoun. Since Final Fantasy IX was entirely text-based with no voiceover, we turned that into a little inside joke: other characters called Quina “s/he,” letting players in on the ambiguity while keeping the dialogue playful.

Time Extension: Regarding characterization, do you remember who came up with the nickname “Rusty” for Steiner? That doesn’t seem to appear in the Japanese version.

Phillips: Oh man, I’d actually forgotten about that one until you mentioned it. In the Japanese script, there’s a scene where Zidane calls Steiner “ossan” or "おっさん". “Ossan” is basically a slangier version of the Japanese word “oji-san" that literally means “uncle". It carries the same meaning—“uncle” or “middle-aged man”—but “ossan” is rougher and more dismissive. In this case, Zidane’s being cheeky—basically age-shaming Steiner, who blows up like, “How dare you call me that!”

When we localized it, we needed an insult that an English-speaking audience would read the same way—and that Steiner could react to with the same kind of overblown frustration. Something like “OK, boomer” might work now, but this was 1999. So we landed on “Rusty.” It played off his armor, and it gave Zidane that cheeky, needling tone. Also, age-based insults don’t hit the same way in American culture, so it avoided that pitfall.

Time Extension: The Japanese version of FFIX has references to older Final Fantasy games, some of which were cut in English. Do you remember why?

Phillips: Honestly, I don’t remember deliberately removing them. What I do remember is: there were definitely references that slipped by us completely. Nobody on the team caught them until it was too late.

That said, the release history of Final Fantasy outside Japan was messy at the time. A lot of fans in the West had only played I, IV, VI, VII, and VIII. II, III, and V had never been localized [correction: Final Fantasy V had actually been localised, as part of Final Fantasy: Anthology the year before]. So even if we had caught every reference, there would have been internal debates about how they would have been localized on the consoles of the time.

Time Extension: Do you have any other memories or insights from working on the game?

Phillips: A couple stand out. Early on, the stage play in the opening—the king’s name in Japanese sounded way too close to “King Lear.” I thought that would be distracting, so I renamed him “King Leo,” after my dad. He loved that.

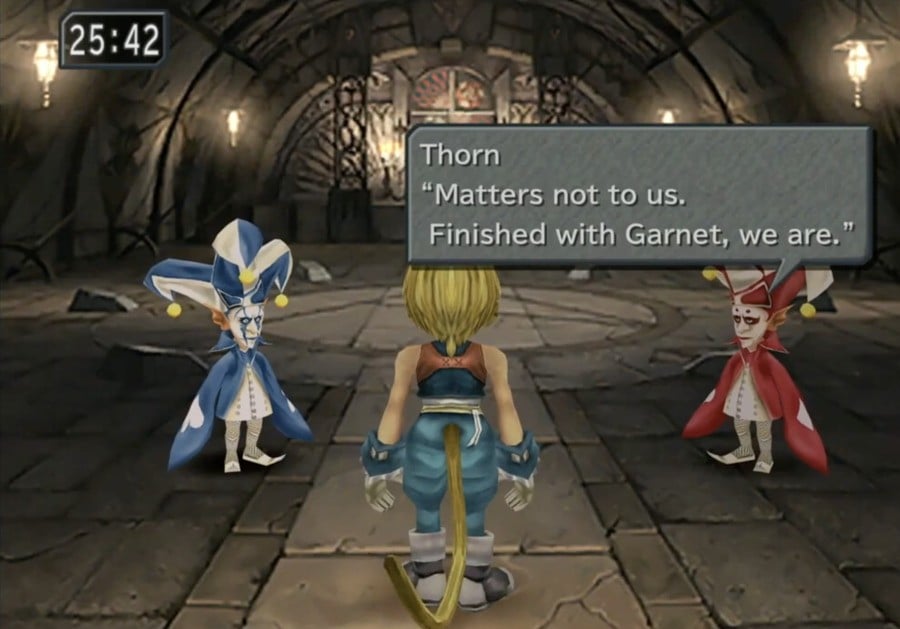

The queen’s two jesters are another fun one. In Japanese, they always speak in unison, but with slightly different archaic endings—quirky, almost Smeagol-like. The endings are actually corruptions of an old form of the “to be” verb, degozaru, which survives today in polite Japanese as degozaimasu. That made them sound both archaic and weirdly unhinged. To mirror that in English, I pitched that one would talk normally, and the other would flip his grammar around like Yoda. So you’d get lines like: “This is an emergency!” / “An emergency is this!”

And here’s a funny what-if: in Final Fantasy, elemental spells usually come in three levels. Someone suggested we make the English levels “-rrific” and “-rama.” So you’d have “Fire,” then “Firrific,” then “Firama.” “Blizzarrific,” “Blizzarama,” and so on. We laughed about it but figured it was maybe a bit too silly. Probably for the best.

Time Extension: With rumors of a remaster going around, would you want your localization reused, or would you rather see a new team take it on?

Phillips: I’d honestly love to see what a new team could do. Localization’s come a long way in the last 25 years, and now translators have tools that make the process so much smoother. Back then, everything was manual. We were using WZ Editor with regex to do bulk changes, version control was literally file timestamps, and we were emailing files back and forth in Outlook. Work got lost, mistakes happened—it was messy.

I think we did a good job of bringing the game to life for Western audiences. But looking back, I wish we’d been sharper about the nostalgia aspect—picking up on more of those deep-cut references to earlier Final Fantasy games. We caught some, we updated some, but others we just missed. I’m sure a modern team—especially one steeped in the series’ history—could make those shine even brighter.

Time Extension: Thanks Brody for your time! We really appreciate you answering our questions.