Japan's obsession with RPGs might lead you to assume that the genre has been part of the country's video game history since the industry began, but that isn't the case.

Prior to the release of Henk Rogers' The Black Onyx in 1984, role-playing games were practically alien to Japan, and the game would trigger a flood of RPGs in the region, effectively laying down the foundations for the likes of Hydlide, Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.

Despite being made by an American, The Black Onyx was never released in that territory. However, in a recent interview with spillhistorie.no, artist Roger Dean reveals that there were plans for its successor to receive a worldwide release.

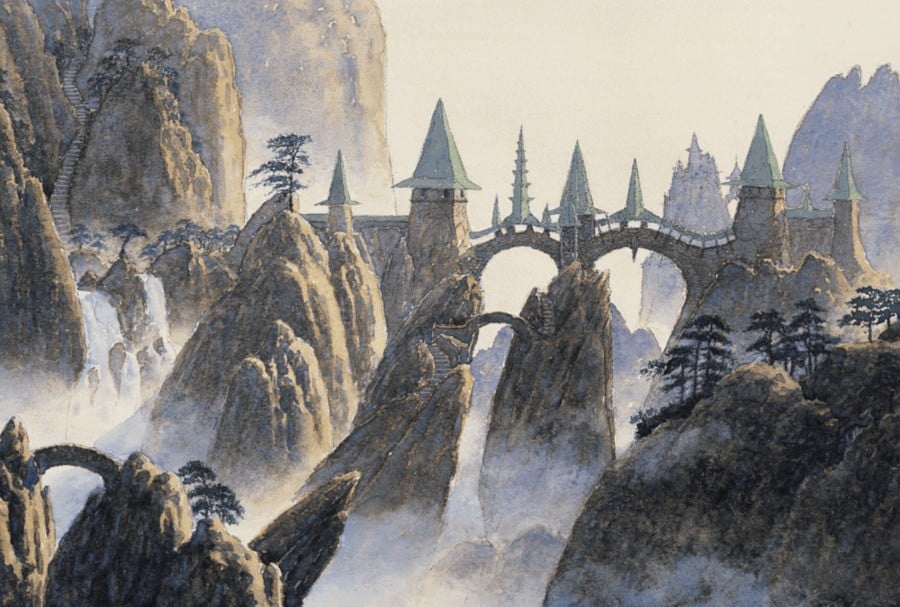

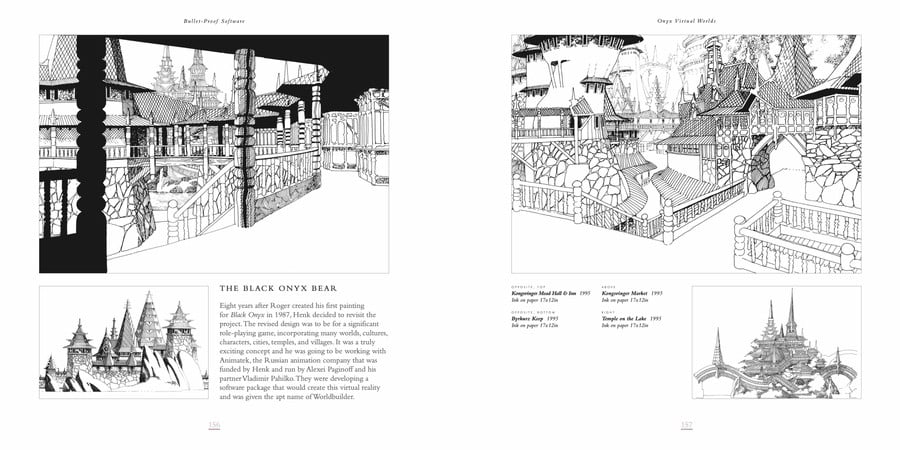

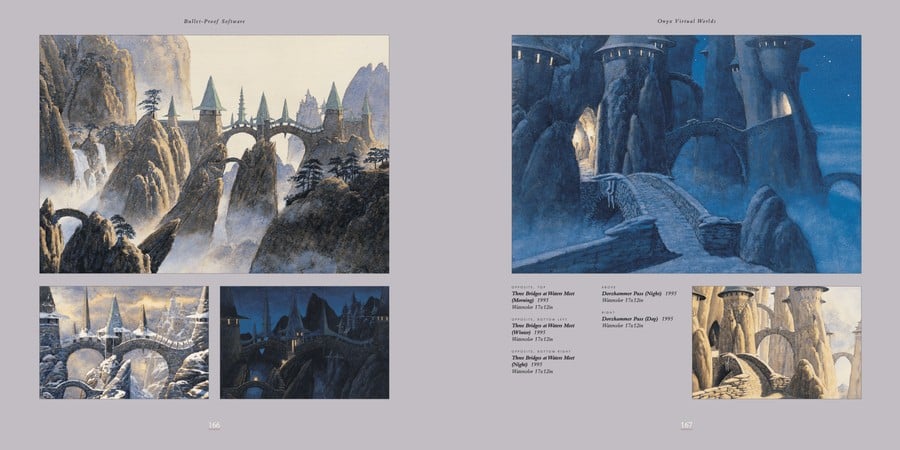

Dean, who created the logo and cover artwork for The Black Onyx, says that "a much, much, more lavish version of The Black Onyx was due to come out in the States," and it was his job to "put together the team that did the content and the packaging, and that included the story, music, landscapes, costumes, everything. I didn’t do it alone, but I put together the team." Development on the project appears to have started in 1995, and the game would have been called Onyx.

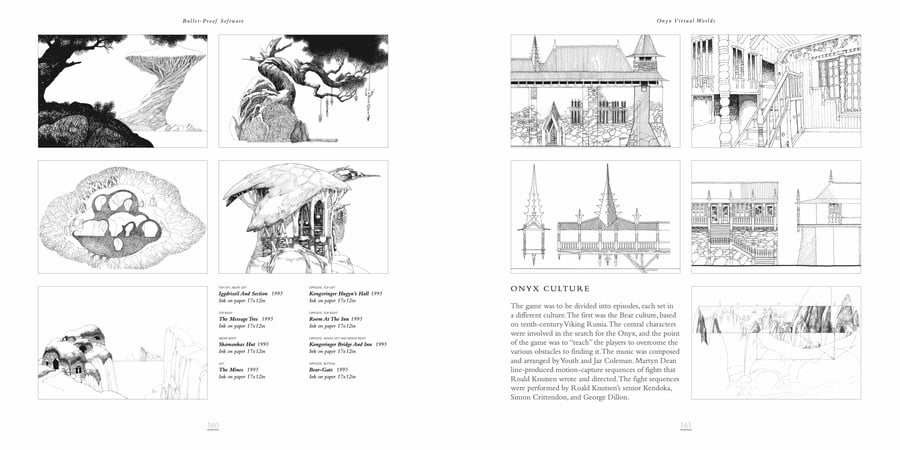

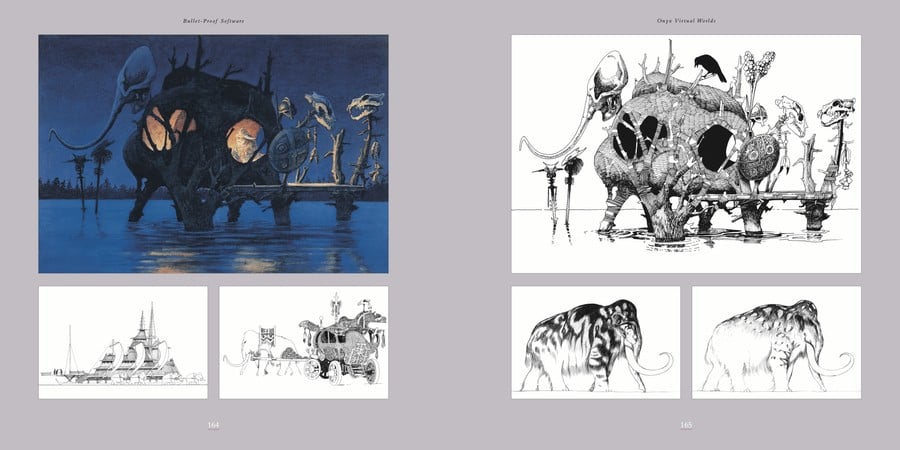

"Eight years after Roger created his first painting for Black Onyx in 1987, Henk decided to revisit the project," reads a description in Dean's Dragon's Dream book which relates to the project. "The revised design was to be for a significant role-playing game, incorporating many worlds, cultures, characters, cities, temples, and villages. It was a truly exciting concept and he was going to be working with Animatek, the Russian animation company that was funded by Henk and run by Alexei Paginoff and his partner Vladimir Pahilko. They were developing a software package that would create this virtual reality and was given the apt name of Worldbuilder."

It would seem that Oynx was intended to have a Virtual Reality component, but sadly, Dean admits that the game didn't progress far enough to be playable. "Henk would probably tell me I’m wrong, but I’m not even sure gameplay was ever fully developed," he says. "The overall concept had to be because we couldn’t structure what we did without that, but we were filling in a lot of gaps. Too many gaps."

He adds:

"I mean, we did a lot of things which were done for the first time. At the time, I studied kendo, which is Japanese martial art with the sword. And my sensei had studied medieval European sword and pole arm spear techniques. For the sword fighting, it was broken up into kata, which is attack, defend, counterattack – sequences that were from real techniques. In a fight you could put it together and it looks so amazingly convincing, and you could watch it from any angle. And we we recorded it in motion capture. So it was very realistic. And it was not just because the motion capture is realistic, but because these were genuine sword techniques."

He also expands on one of the game's unique gameplay concepts:

"We developed a process that Henk called Track and Field. Track was when the characters followed a specific route, and Field was when they could wander wherever you liked. They couldn’t wander over the whole world because they’d get lost and it would be boring. You had to have a mechanism to bring them back, but you needed them to follow a path.

So you could do it like a movie where there was a sequence that was completely constructed. You could watch it from different angles, but you it was a complete construction, but then you could break off into a game. If for instance it was like Lord of the Rings, they could be climbing the mountain path, but when they’re in the dragon’s lair, then they’d come into the field – the game aspect, where they can wander wherever they want. But once they’re out again, they’re back on the track.

So there’s bits when you can just watch it, it looks great, and then there’s bits when you’re frantically interactive."

Some of the artwork for this title appears in Dean's book, Dragon’s Dream. "It was a real shame that it never happened, because while the technology has moved on, the design would still be valid today," Dean tells spillhistorie.no. "The music is incredible."

When asked if there was a chance the project could potentially be rebooted, Dean seems hopeful. "I think Henk Rogers would like to see it published. He owns the game, and I own the artwork." He hints that it was "too advanced" for the time, and "would have needed 24 CDs for each episode. DVDs arrived in the middle of it, but that would have only divided the number of CDs by three."

Even though the game never got released, its influence is still being felt. "Two weeks ago, I had a visit from Henk Rogers," Dean explains. "He’s doing a book called 'The Perfect Game' about Tetris, and he’s doing an audiobook. And in that, he talks about different projects, including Black Onyx. For Black Onyx, he used some of the music that we created for the project, and it was really good by any standards. It was a great piece of music, not a great piece of game music, but a great piece of music. Even the music should be published. It hasn’t been, but it should be."

Dean adds:

"We did it in collaboration with two people called Youth and Jaz. Jaz Coleman was orchestral-minded, but he was also a singer for a band called Killing Joke. So he had his rock and roll credentials. But he worked with Prague Symphony Orchestra and things like that. Youth (Martin Glover) was very much into electronic music. He had a band called The Orb, and he worked with people like Paul McCartney. Oh, he did all kinds of stuff. But his big interest was electronic music at the time.

Between them, one producing, one arranging, they made a lovely soundtrack. And it had people like Steve Howe from Yes performing on it."