Media tycoon Robert Maxwell’s influence on the UK and international games’ software industry is the stuff of legend. As Dan Ackmerman’s writes in The Tetris Effect, Maxwell’s part in the international battle for the rights to Tetris resulted in legal battles between his son, Kevin Maxwell, Nintendo and the Soviet state – the ramifications of which would be massive for this video game publishing company, Mirrorsoft.

It was an Intellectual Property war that Maxwell would end up losing, but the battle for Tetris tells only a sliver of the story around Maxwell’s involvement in the history of the video games industry. Based on archival research of Maxwell’s companies, this is the surprising and controversial story of Maxwell’s rise from the sunrise industries of Sinclair computers to the establishment of what was, at the time, the UK’s biggest games company.

Born Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch in Czechoslovakia in 1923, Maxwell fled from the spectre of Nazi occupation (most of his family would perish within the walls of Auschwitz) and enlisted in the Czechoslovak Army in World War II; he was eventually decorated with the Military Cross following his exemplary service in the British Army. Naturalised as a British subject in 1946, he changed his name via deed poll and began building a publishing empire which began with Pergamon Press but would eventually encompass the British Printing Corporation, Macmillan Publishers and Mirror Group Newspapers, the latter of which is perhaps the organisation he is most associated with today. In 1964, he was elected as Member of Parliament for Buckingham; the culmination of an amazing rags-to-riches story.

The Spectrum Connection

Maxwell’s association with video games begins in 1971, when the Advanced Instrumentation Modules (AIM) Group shared premises and resources with Sinclair Radionics at St Ives in Cambridge. As Rodney Dale writes, AIM’s chairman, Gordon Southward, "persuaded Robert Maxwell, head of Pergamon Press, who had long been an investor in the enterprise, to invest 'just a little more'". Maxwell would only agree if he was given complete control of the AIM group. Eventually, Clive Sinclair floated the £25,000, but the AIM group was placed into receivership and dissolved anyway. Fourteen years later, following the unbounded success of the Sinclair ZX81 and ZX Spectrum microcomputers, the January 1984 release of the Sinclair QL (Quantum Leap) was much anticipated.

However, Sinclair, as it had done so often in its history, tasted the bitterness of defeat where there should have been the sweetness of victory. This was mainly due to Sinclair rejecting the gaming market by developing bespoke hardware, which as Dale notes was a "deliberate Sinclair policy to discourage software houses from writing games". The QL was hyped by Sinclair to be a ‘serious’ computer where games were seen as a waste of time. As seen so many times since in varying degrees by Nintendo, Sega, Sony and Microsoft, ignoring your core customer base often results in catastrophe. The QL failed at launch. By April 1985, manufacturing of the QL had ceased; low demand had led to thousands of the machines being stockpiled and Sinclair sustained an £18M loss.

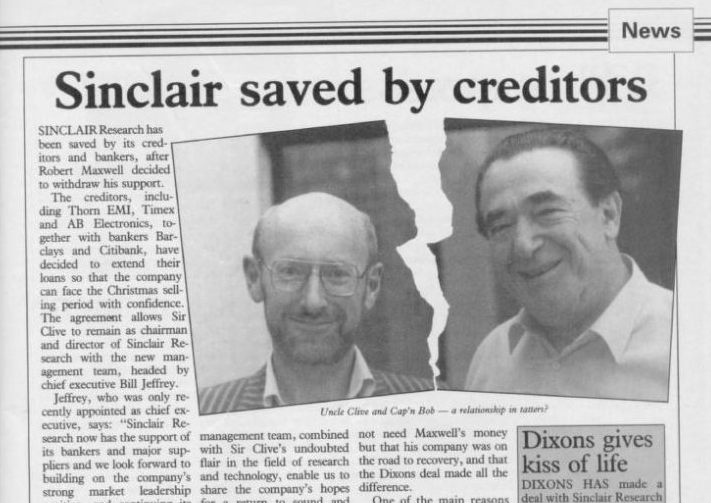

In June 1985, with Sinclair on the precipice of bankruptcy, Maxwell, who now owned Mirror Group Newspapers, bid for the company. He was pictured on the front page of his own newspaper, The Mirror, holding the very same newspaper with the headline, "Maxwell Saves Sinclair".

Before Sinclair could be saved and potential could be realised, Maxwell needed to reduce the stockpiles of Sinclair hardware. There were two ways to do this. The first, executed the day after the takeover, saw 400 employees dismissed from the Timex factory in Dundee, Scotland, where Sinclair computers were manufactured. The second proposed (but never realised) strategy was to export Sinclair computers to the USSR and its satellites, namely Bulgaria. Widely seen as fanciful due to rules concerning the export of microprocessor technology to the Eastern Bloc, Sinclair already had test sites for educational use of the ZX Spectrum, which were expected to be replaced by exports of the more powerful and stockpiled QL enabled by Maxwell’s connections to Eastern Bloc nations, via Pergamon Press.

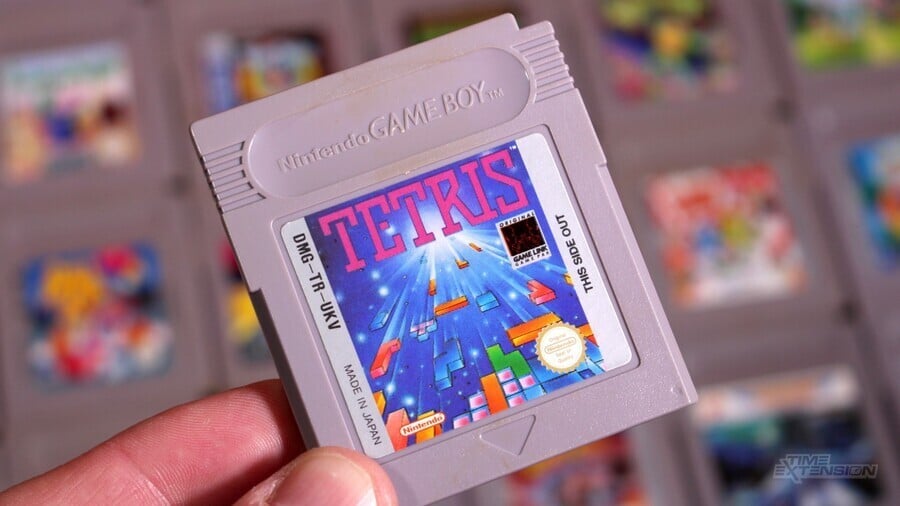

By this point, Mirrorsoft, Mirror Group's video game and software arm, had already published games from Robert Stein’s Andromeda Software catalogue – including Spitfire 40, which was as unsurprisingly successful in Britain as it was unsuccessful in West Germany – as well as acquiring limited distribution rights to Tetris, the game that would eventually be seen as the 'killer app' for Nintendo's Game Boy console (more on that shortly). Indeed, Maxwell counted Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev as both a political ally and personal friend. However, the export arrangement was the last news to be heard about the proposed partnership between Maxwell and Sinclair, before Maxwell quietly pulled out of the deal in August 1985.

Framing The Mirror

By 1985, Mirror Group's London-based video games and software publishing arm, Mirrorsoft, had emerged as a rival to more established UK publishers such as US Gold in Birmingham and Ocean in Manchester. Unlike US Gold and Ocean, Mirrorsoft’s history is not well known, with the most authoritative written by former Mirrorsoft employee Richard Hewison for Retro Gamer magazine, who interviews the founder of Mirrorsoft, Jim Mackonchie, and other ex-Mirrorsoft employees. Initially, Mirrorsoft’s focus was on the underexplored educational video game market, and as early as 1983, it was demonstrating the potential synergy between brands via Mr. Men, a children’s book series which appeared as a cartoon strip in the Daily Mirror and was repurposed as an early video game release for Mirrorsoft.

Andromeda Software went on to produce first-party titles for Sega’s consoles, including Ecco the Dolphin

Another piece of educational software, Caesar the Cat, demonstrates some of the intricacies around Mirrorsoft’s business. It is widely understood that Andromeda Software, the Hungarian software and hardware reseller and the focus of much of the attention of the tug-of-war involving Tetris (again, we're getting to that bit), was brought into the Mirrorsoft fold on the back of Maxwell’s connections in Eastern Europe. Yet Hewison notes that Andromeda "submitted Caesar the Cat as an almost finished product". While Hewison does not give a date, the original cassette tape shows that Caesar the Cat was released on the Commodore 64 in 1983, prior to Maxwell’s 1984 takeover. Andromeda Software was itself part of a coterie of Hungarian finance and tech companies which initially traded under the Novotrade Software name and went on to produce first-party titles for Sega’s consoles, including Ecco the Dolphin and iterations of Konami’s Contra series before changing its name to Appaloosa Interactive Corporation in 1996.

The significance is considerable, in that without Mirrorsoft’s input, these games may not have come to pass. Caesar the Cat was the first game developed under the Novotrade name, and over the next 23 years the firm went on to develop or publish over 50 games across a range of video game platforms. In so doing, they had significant sway in the development of software for the Japanese, European and American video games industry.

Jim Mackonachie, who oversaw the inaugural releases of Mirrorsoft games, including Caesar the Cat, founded Mirrorsoft while undertaking his day job as development manager at Mirror Group. The arrangement continued as normal under Mackonochie’s direction even for the six months following Maxwell’s takeover in 1984. In spite of a 1985 interview with John Minson in Crash magazine where Mackonochie was convinced of the growth potential of educational software, the takeover altered the focus of the company. The acquisition by Maxwell changed the direction of Mirrorsoft away from educational software and towards entertainment games and business software, with much of this focussed on Mirror Group's commercial interests and Mackononachie’s own interests.

The acquisition by Maxwell changed the direction of Mirrorsoft away from educational software and towards entertainment games and business software

Of special note is the 1986 release Fleet Street Publisher, a desktop publishing suite, its title laced with irony given Maxwell’s announcement that the Mirror newspaper would no longer be printed on the famous London street from August 1985. As a result, 2100 jobs at The Mirror were made redundant and Mirror Group saved £40M, with publishing outsourced around all areas of the Maxwell empire. Injury was compounded by insult when communication between disparate sites, so difficult with conventional publishing techniques, was enabled by employing the desk-top publishing software which subsequently formed the basis of Fleet Street Publisher and would eventually become Timeworks Publisher in the UK and Publish It! in the US.

In addition to Mackonochie’s background in printing, he found a natural affinity with Maxwell in a previous career in the British armed forces, where both had served: Maxwell in World War II in intelligence and infantry and Mackonochie more recently as a Royal Navy officer. As computing power increased, home computers and simulations became well established in the 1980s with stellar titles like Micropose’s Gunship and F-19 Stealth Fighter. Mackonochie’s influence could be seen in the releases of that time, including Spitfire 40, Strike Force Harrier and Biggles. His links were central to Mirrorsoft’s expansion into the US market, particularly with Spectrum Holobyte, which developed the influential F-16 flight simulator Falcon, published in the UK by Mirrorsoft.

Another Brick In The Wall

To Nintendo fans, Maxwell is perhaps most famous for being one of the various parties bidding for the console rights to Alexey Pajitnov's seminal puzzler Tetris. Following its discovery by Robert Stein, owner of the aforementioned Andromeda Software, an attempt was made to secure the computer rights from Pajitnov himself – but Stein was initially unaware that Pajitnov wasn't able to give that permission, as the concept of an individual owning the IP rights to something was relatively alien in the communist USSR.

Miscommunication led Stein to assume that he had secured the rights and Andromeda quickly sold the PC version to Spectrum HoloByte, which was effectively Mirrorsoft's American division at this point. This iteration would prove to be incredibly successful, and plans were made to expand it via sub-licencing. Stein's agreement with the Russian agency responsible for monitoring the import and export of software, Elektronorgtechnica (Elorg for short), covered Tetris on personal computers but did not cover console, handheld or coin-operated platforms – still, this didn't stop Stein from informing Spectrum HoloByte and Mirrorsoft that he would soon have these rights sewn up. As a result, Mirrorsoft entered into licencing deals with Atari and Sega, which resulted in arcade machines and home-console versions of the title. Tetris was now mired in an intricate web of licencing and sub-licencing, yet Elorg had yet to receive any royalty payments on sales (there was, at this point, still no question of Pajitnov personally gaining anything from the deal – this wouldn't really change until the establishment of The Tetris Company, but that's another story).

Things came to a head when BulletProof Software's Henk Rogers – who had secured rights for Tetris distribution the Nintendo Famicom in Japan via Spectrum HoloByte – met with Elorg to discuss creating a version of the puzzler for the upcoming Game Boy, which he felt was the perfect hardware fit for the title. When Rogers produced a copy of the already-released Famicom version during his meeting with the Russian agency, the result was catastrophic; they didn't even know this iteration of the game even existed. The bombshell predictably placed Robert Stein in hot water; he had been trading rights he simply did not own.

However, while Rogers had been the bearer of bad news, he was placed in an advantageous position. He explained how profitable licencing the console and handheld rights to Nintendo could be, and was able to pay Elorg a considerable sum there and then – which, given that it had received practically nothing from Andromeda at this point, made a huge impact. Despite Maxell's son Kevin flying in to meet with Elorg at the exact same point that both Rogers and the increasingly-exasperated Stein were hastily trying to negotiate their way to victory – and his father's threats of calling upon Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to force a deal – Elorg ultimately decided to grant the console and handheld rights to Nintendo via Henk Rogers, a move that effectively cost Spectrum HoloByte and its parent company Mirrorsoft untold millions and turned the Game Boy into one of the best-selling consoles of the era.

It was a bitter blow for Maxwell and Mirrorsoft at a time when the company's star in the video game world seemed to be heading in the right direction, but things would get significantly worse.

Mirrorsoft: The Lost Rival To EA, Ubisoft And Activision?

On 5th November 1991, Maxwell's naked body was found floating in the Atlantic Ocean, and an inquest in December of the same year determined that his death was caused by a heart attack combined with accidental drowning as he fell from his luxury yacht, the Lady Ghislaine. Following his passing, news of his shady business practices began to filter out; Maxwell had siphoned off hundreds of millions of pounds from his companies' pension funds to save his empire from falling into bankruptcy. In 1992, his group of companies finally collapsed and his son Kevin, who had unsuccessfully tried to secure the Tetris rights just a few years before, was declared bankrupt with debts of £400 million.

Quite apart from Tetris, Robert Maxwell has wielded extensive influence over the early video games industry in the UK. Rarely was this involvement straightforward: the most complex tale of a ‘missing’ £14M which was allegedly held by F-16 Falcon publisher Spectrum Holobyte, was the source of intense newspaper scrutiny in the summer of 1992 and was seen as a great hope to plug the gaps in finances left by his death in 1991.

Nevertheless, the red threads of his influence stretch from 1971 St Ives through to the present day; arguably many of the greatest developers in the UK – such as Probe Software, Bitmap Brothers and Sensible Software – would never have enjoyed the exposure and promotion they had without Maxwell’s involvement. Via its Image Works sub-label, Mirrorsoft published best-selling and critically-acclaimed titles like Speedball II: Brutal Deluxe, Xenon 2: Megablast, Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles, Back to the Future III, First Samurai and Mega Lo Mania; while we'll never know if all of these games would have vanished had Mirrorsoft not been involved, there's a fair chance that the landscape of the UK games industry would have looked a lot different.

Given Mirrorsoft’s position at the apex of games publishing in the early 1990s, it can only be supposed what would have happened if Mirror Group was still around today and if Mirrorsoft could have offered a genuine British alternative to EA, Ubisoft and Vivendi; its involvement in all areas of multimedia – from selling video games via a cable network to digitising The Guinness Book of Records on CD-ROM – suggests that it had in-built solutions to all of the changes in the media landscape that wrought such havoc through the 1990s. In short, it could have become a real player, perhaps even pre-dating Eidos as one of Europe's most prolific publishers.

However, given Maxwell himself couldn’t live to see his electric dreams become reality, all that remains is to tell the story of how a Czechoslovakian refugee built a video game empire, one brick at a time, long before he 'lost' Tetris.

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Mon 26th August, 2019.

Comments 29

Kind of pales in comparison to the current news about Maxwell.

@Franklin Interesting to see Cap'n Bob's murky past still comes back to haunt his family.

Great article! Thanks @Strider

So many games and publisher names that I remember incredibly fondly from way back in my kiddie days

Looks like he also lost his neck

@antster1983 Don’t think the stink will ever go away.

Looks like he also lost his neck

@resa87 @DinnerAndWine Great minds

@Strider Great piece! I enjoyed reading this while I ate breakfast and prepared for the morning ahead. I wasn't aware of any of this info, so I found it very informative and fun.

Great article. Thanks to everyone involved.

@resa87 @DinnerAndWine

Looks like he also lost his neck

Lesson from Tyra Banks about No Neck Monster.

@Damo Kim Justice made a video about Mirrorsoft back in 2016. A great video about the label, and its owner Cap'n Bob. The Tetris story is recounted in it too, as is the Mirror Group Pension Fund scandal.

https://youtu.be/GHfjANn5J04

I hold no sympathy for this man! The way he and his son Kevin damaged Oxford Utd in the late 80's/90's, makes me hate him.

@antster1983 I'll check it out! Big fan of Kim's stuff

So wait was this a good thing he lost or not im so confused???

@ShinyUmbreon Well, if he hadn't, we wouldn't have had a lot of the early Tetris games that came to Nintendo, including the famous Gameboy version. They'd have probably looked a lot different. Not to mention, Tetris may have never been bought back from Elorg by The Tetris Company. And without that, there's be no Tetris 99.

In short, things wouldn't have to be necessarily better or worse, but the state and legacy of Tetris would be quite different.

Great article, fantastic slant on his business and life. Taking money from pensions is horrific, whether he took his own life or went overboard taking a slash, there can be little sympathy

Conflict: Europe was a great little game and one of theirs I remember.

This is an excellent article, I didn't know too much about this.

This BBC documentary is essential viewing for those wanting to know more about Tetris' murky history: https://youtu.be/NhwNTo_Yr3k

I understand that Robert Maxwell died of a heart attack combined with accidental drowning but what was the reason he was found naked? What the heck was he doing on his yacht?

The classic gaming history book Game Over by David Sheff goes into a lot of detail in this story. Maxwell and Stein et al came out looking like total fools while Henk Rogers ended up a hero. Really cool guy btw. He and Pajitnov are lifelong friends and still own the Tetris Company together.

What an interesting article - thanks for all the research that has clearly gone into this. In this day and age it seems almost unbelievable that companies/individuals were able to sell IP they didn’t actually own onto the likes of Sega and Atari.

This article could had been more objective if I were involved in its creation.

The gaming historian on YouTube has a great video on this.

Ah yes, saw the gaming historian video on this. Would make a great movie.

So many different Tetris’s could exist right now had these business deals gone differently.

The only good thing that Robert Maxwell did in his life is support Israel. As for the rest of the things he did not so much.

Mega Lo Mania was an all time favorite game of mine for the Amiga 500 where the in game speech was quite impressive at the time and actually added to the game play. Nice to know the history.

Great article. I remember being introduced to Tetris via the Tengen version on NES. One of my mom's friends kids had it and when she went to visit them with me I played it. After that I couldn't find it for the life of me all I found was Nintendo's version. When I told people that that wasn't the version of Tetris I played they all though I was crazy.

After awhile I just assumed either he had a copy from another country (I was young and didn't know about region locking) or an early version of the game. I didn't find out till the late 90s thanks to the internet that there was indeed 2 versions of Tetris on the NES.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...