Released in 1991 across Amiga and Atari ST, Utopia: The Creation Of A Nation was one of the more novel attempts to do something new with the successful formula set out by the popular city builder SimCity,

Not only did it change the setting to a sci-fi environment, placing players in charge of populating an entire planet rather than a single city, but it also increased the focus on combat and defence, allowing players to amass an army of tanks and spaceships to defend themselves against their neighbours.

Developed by the UK developer Celestial Software, in collaboration with Gremlin Graphics, it proved to be an incredibly popular title with players at the time and even got ports for DOS computers and the SNES, but has ultimately failed to leave as much of an impact on the genre as SimCity, instead becoming something of a hidden gem that only occasionally gets brought up online (typically by those who played back when it originally came out, or companies like Evercade who have since reissued it in the present day).

Having previously explored other '90s strategy games on the site, including Bullfrog's 1990 Atari ST and Amiga classic Powermonger, I wanted to take the time to look at some other titles from the period, which brought me back recently to thinking about Utopia and wanting to look into how the developers approached the game's design. So I reached out Graeme Ing, the co-creator of the title, to see whether he'd be interested in talking to me about its development.

Fortunately, he was more than happy to answer my questions, giving me a bit more detail not only on Utopia, but the company where it was originally born, Celestial Software.

Celestial Software was a development studio that was formed in the mid-to-late 80s, after Ing quit his job at a company called K-Bytes, situated in Chandlers Ford, UK. Armed with a small business grant from the government that paid "£40 a week" — an amount Ing describes today as "more than it looks if you factor in inflation" — it was initially set up to develop Amiga games for a London-based producer named David Lester, who was operating a publishing label at the time, called "Impressions".

"Before I quit my job I had run into a publisher in London named David Lester operating the Impressions game label," says Ing. "Great guy. Very supportive. Early on, he invited a handful of young games programmers from around the Southern part of England to a lunch meeting in London where he promoted himself as producer and publisher. That led me to start working on some titles for him.

He continues, "My initial work was to create a Choplifter-like game for the Amiga, but that got cancelled. Then I worked on the two sports games (Supreme Soccer and Championship Cricket), before getting to work on another title for Impressions, a shoot 'em up called Raider."

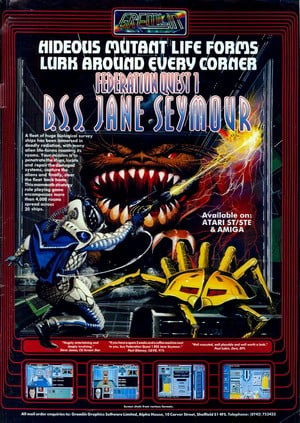

It was while working on Raider that Ing would find himself talking one day with his close friend and future collaborator, Robert Crack (the co-creator of Utopia), about the work he was doing for Impressions, leading Crack to volunteer his help with the artwork and music on Celestial titles going forward. Together they worked out of Ing's house, completing the remainder of the work that needed to be done for Raider, before coming up with a pitch for a sci-fi role-playing-game called BSS Jane Seymour (later retitled to Spacewrecked in the US), which they pitched to Gremlin Graphics — the company that would also end up picking up Utopia.

"After Raider, Rob and I designed BSS Jane Seymour and immediately started work on the prototype," says Ing. "With that in hand we went around visiting over half a dozen games publishers throughout England, demonstrating the prototype and trying to get a contract. I seem to remember we didn't approach Impressions because either David Lester had moved on, or we believed we had a bigger hit on our hands and wanted a larger publisher.

He elaborates, "I can't remember all of the publishers who we demoed it to now, but there were some medium to large players in the UK games industry. We were, of course, aware of Gremlin Graphics as a publisher but we had yet to play any of their games. So, at some point we drove up to Birmingham to meet with Ian Stewart, head of Gremlin, who had a tiny office in the city. Ian and his team were impressed with the game's originality and "3D" graphics and asked me to put together a detailed completion plan to finish the game. I broke down every little sub-system of the game that needed to be coded, and all the graphics, and gave Ian a document that outlined everything to be achieved almost day by day. I remember he said: 'When do you get time to go to the bathroom?'"

BSS Jane Seymour would end up releasing for the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and MS-DOS in 1990 and launched to fantastic reviews from publications like ACE, CVG, and The Games Machine, among many others, so it made sense to Gremlin Graphics to see what else the two developers Ing and Crack might have up their sleeve. It was at this point, the two began talking about their shared love of Maxis and Broderbund's title and what they would do given the chance to make their own take on the city planning genre.

Their initial idea was to make a medieval fantasy game, named Fantasym, with development on the project starting in June 1990. However, after just one month, the idea started to morph into a sci-fi title, with Ing deciding that spaceships would be far more easy to move around a map intelligently than individual armies travelling by road.

"Rob and I were very active on the Amiga games scene and probably bought SimCity the year it came out," says Ing. "We both liked the ability to play city planner and get feedback on our efforts, like power, crime, traffic and so on. We spent months trying different city layouts. It gave us the ideas for a variety of building types each contributing something to the whole, an idea we would carry into Utopia."

"Our chief idea was building a thriving colony on a new world. Having loved the feedback mechanisms in SimCity, we came up with some similar metrics and the Quality of Life indicator, which were the goal of creating a perfect colony. We wanted to add a trading mechanism too. Complete control was the style of gameplay we wanted. You needed to learn how to balance a complex matrix of variables to master your new colony. We basically wanted it to be more complex than SimCity – a game you could really sink your teeth into. We gave each world different properties like terrain types and resources so that each world would offer a unique challenge."

Much as Gremlin Graphics had done previously with BSS Jane Seymour, the publisher again offered to help turn Celestial Software's ideas into a reality, agreeing to help fund the project and assigning James North-Hearn to oversee the title, alongside another Gremlin employee, named Sean Kelly. According to Ing, Sean Kelly, in particular, would go on to contribute a ton of ideas to the game, even earning himself an additional game design credit. North-Hearn, meanwhile, proved to be just as helpful, advising the developers and offering his assistance wherever it was needed.

"Sean was really good at his job," Ing recalls. "We had many a discussion about gameplay or interface style and even though the original concept was mine and Rob’s, most of Sean’s ideas made the game even better.

"James, on the other hand, was like the CTO and executive producer," he adds. "We all reported into James and then indirectly into Ian Stewart. James was a good technical mentor, offering solid solutions to technical issues in the game. He was responsible for every title on every platform and heavily involved with QA. I remember he played hardball with fixing bugs. In fact, I probably owe my career-spanning great relationships with QA departments to him, and learning how to triage and qualify bugs."

Upon starting a new game in Utopia, players are able to enter a tutorial map or select from one of 10 different scenarios, with each of these being named after a different alien race and containing new challenges and obstacles to overcome. Within each of these stages, you will initially start out assessing what types of buildings you already have available, before having to decide what other infrastructure you'll need to construct to grow your colony and keep everything running smoothly.

Some of the main issues you'll need to address includes having enough housing, food, and security to keep your budding civilisation happy; setting up potential revenue streams from your mining operations and other industries to keep your colony's finances in the black; and investing in new technology to make sure you have enough weapons and defences at your disposal, once the neighbouring aliens start to attack. It's this balancing of different priorities that makes the game so compelling to play, with the player having to constantly juggle these different sets of responsibilities or wind up dealing with high crime rates, money problems, and a plummeting quality of life meter.

"Having loved the random events in SimCity, like the tornado and Godzilla," says Ing, "We decided to not only have random events but to introduce alien races as well, turning it into an espionage and combat game too. Like terrain, aliens would vary per world, making a whole series of unique worlds to master.

He continues, "I wanted it to be challenging, to take time to master. I know the alien races were particularly difficult, in that some races had a high aggression factor and moved faster than the player to build facilities, but in my mind it was okay to be beaten up a few times before you learned their unique strategies and potential flaws."

As you'll no doubt be able to tell from looking up screenshots or searching online for let's plays, all of the the action in Utopia is presented from an isometric angle, but this apparently wasn't always the case. In the very beginning, the plan was for Utopia to share SimCity's top-down perspective — something you can actually see in images included in early screenshots posted as part of a column Ing wrote for the magazine Games-X back in April 1991. However, Gremlin encouraged the team to think a little more ambitiously, suggesting an isometric perspective similar to the Bullfrog classic Populous.

In order to help them accomplish this, Gremlin offered Celestial Software the services of one of its most talented artists Berni Hill, whose credits up until that point had included titles like 3D Galax (Amiga), Federation (Atari ST), H.A.T.E: Hostile All Terrain Encounter (Atari ST/Amiga), and Venus the Flytrap (Atari ST). He would be responsible for creating the icons for the various buildings as well as drawing the alien advisors, who would give you tips on where you were going wrong.

"The folks at Gremlin wanted to push the envelope and turn it isometric," Ing tells me. "A fabulous idea so I went away and wrote the isometric engine from scratch, not too difficult a task given the Amiga’s incredible video chipset like the blitter chip. Gremlin was working on so many games platforms that I might have taken some ideas from other isometric engines, I honestly don’t remember, but I’m pretty sure we didn’t have a 68000-based isometric engine yet. It definitely made a huge difference to the appeal of the game."

Besides Sean Kelly, James North-Hearn, and Berni Hill, another one of Celestial's key collaborators who should be mentioned is Imagitech Design Limited's Barry Leitch, who provided the music for the title — including a memorable rendition of Pachelbel's Canon for the game's title music.

As all of these various different parts fell into place, the small team continued working away on the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST versions of the game, with these titles eventually being released in stores in September 1991.

Unsurprisingly, at the time, the team were nervous to find out what players outside the two game companies would make of the title, and remarkably, the immediate reaction from the gaming press at the time ended up being exceptionally positive.

Advanced Computer Entertainment (ACE) magazine, for example, gave the Amiga version its "ACE Trailblazer" award in the October 1991 issue, describing it as "stir-fry" software due to the way in which it expertly blended the administrative elements of SimCity with the "hot Populous-style 3D view". And they weren't alone in their comments either. Elsewhere, the magazine The One also gave it an exceptionally high score of 93%, once again describing it as "a cross between SimCity and Populous", but clarifying that it was potentially good enough to be considered "a rival to both".

Following the success of the Amiga and Atari ST titles, Ing ended up putting Celestial Software on hold and got a job internally at Gremlin Graphics, where he provided insight for the PC port (programmed by Mark Glossop) and also worked on the SNES port of the game. This SNES version ended up being released two years after the original, in 1993, and saw Gremlin credited as the sole developer, with a string of different publishers, including Jaleco's USA branch, being responsible for its distribution across various regions.

"I remember that was a significant challenge trying to recreate Utopia on the SNES's 65C02," says Ing. "I had done 6502 programming before so I was very familiar with the chip, but it was difficult due to the chip's limitations compared to the 68000. It would have been much easier to go from 65C02 to 68000, but the other way required a lot more creative design and coding."

He adds, "For a start it's an 8-bit chip compared to the 16-bit 68000, so a lot of addressing logic had to work with both the upper byte and the lower byte instead of an entire word at once. The 65C02 had just 3 registers (technically only X and Y because the Accumulator register was "destroyed by so many operations), compared to the 8 data registers and 8 address registers in the 68000, each of which was 32-bit. So even ignoring the powerful blitter chip in the Amiga for moving large quantities of display memory around, in the 68000 it was easy to move 4-bytes at once in those registers than 8-bits at a time on the 65C02."

In the end, Utopia's SNES port ended up being pretty faithful translation of the the other versions that were available on the market. Not only was it designed with compatibility for the SNES mouse in mind, letting players use the Mario Paint accessory to navigate its menus much as they had done on the previous platforms, but it also came packaged with a built-in save battery to let players retain their save data, allowing them to switch off the console and pick up where they left off.

The only major differences were a bunch of new designs for the alien advisors to make them look slightly "cuter", as well as a revised UI that presented the options on an L-shaped bar at the bottom of the map as opposed to a sidebar, and the addition a slightly larger grid positioned just slightly above the terrain to better illustrate what building you had currently selected.

Despite being pretty much the same experience as the one released on Amiga, Atari ST, and DOS, the reviews for the SNES version ended being a bit more critical than those received by the previous versions.

The German gaming magazine Maniac, for instance, gave the game 69%, saying it had "keine chance" ("no chance") competing against SimCity, which had also been ported to the SNES by Nintendo a few years earlier, criticising Utopia's "meager graphics" and "confusing controls".

Meanwhile, Nintendo Magazine System, ended up adding to these complaints elsewhere, describing it as "more like a Sociology lesson than a video game" and suggesting that while it offered more "interaction" than SimCity and greater "depth" than Sensible Software's real-time-strategy game Mega-Lo-Mania, it was ultimately trying to do "too much" to be fun.

There were some positive reviews, however, with the main one we could find coming courtesy of the UK magazine Super Gamer, who gave the title 85%. In this review, they described it as "only for games players who have a galaxy of patience" but praised the graphics as an improvement over Infinity Co., Ltd's Populous port and called its depth of detail "truly astounding". One of its staff writers Ryan Butt also went on record as calling it "one of the most detailed and compelling strategy games I’ve played in a long time", stating "I strongly recommend Utopia to anyone seeking an awesome challenge. However, don’t play it unless you’ve a lot of time on your hands!"

After the release of the SNES port, Ing continued working behind the scenes at Gremlin, contributing a couple of Amiga CD titles, before coming out with a sequel to Utopia in 1994, called K240.

K240 was released exclusively for Amiga computers, and, similar to Utopia, saw players once again building colonies in space, with the focus this time being on inhabiting a series of miniature asteroids as opposed to one large planet. For Ing, this was an opportunity to try to expand on the concept further, after years of ports, and ultimately became his favourite title in the series, despite arguably being much less well-known than its predecessor.

"We wanted to do a sequel but very different," Ing tells me. "So I started experimenting, writing an asteroid simulation engine. I really enjoyed the limited real estate you had to build your colony on, coupled with your colonies all moving around the map. It was a great dynamic, I think. I also think the tech system in K240 was better too, being able to buy so many cool gadgets from the corporation whose name escapes me right now."

K240 would end up receiving strong reviews from publications at the time, including CU Amiga (who gave the game 91%), and seemed to be successful enough to warrant a follow-up for PC, named Fragile Allegiance in 1996. However, by this point in time, Ing had moved on from Gremlin, joining Sony Interactive Studios America. From there, he continued working as an engineer in the tech & games industry for the next few decades, while also becoming an award sci-fi and fantasy author.

Reflecting on the days of developing for the Commodore Amiga today, he has a lot of positive memories of what it was like getting the best out of the hardware, and has even told me he is thinking of resurrecting Celestial in the future to work on new titles for the machine.

"I miss those assembler days so much," he tells me. "It was just us and the hardware chips — nothing else. No libraries. No frameworks. Code had to be fast, efficient and fit in tiny amounts of memory. Assembler programming was significantly more satisfying than anything I've done since. Teams were small and we worked closely together to fit the best game we could into the machine. That meant working together, brainstorming together, and socializing together. Working at Gremlin Graphics was a great experience for me — across all the games I worked on there."