After the news was shared online earlier this year that Monolith would be closing its doors for good, there were a lot of tributes written about the studio's 30-year-plus history.

As you'd probably expect, many of these went on to celebrate the company's involvement in the development of groundbreaking first-person shooters, such as Blood, No One Lives Forever, and F.E.A.R, as well as its work on licensed games like Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor and its sequel. But the reality is the company's output was actually a lot more interesting and diverse than many of those accounts would have you believe, featuring a ton of other lesser-known titles that have since gone on to generate small but passionate followings that continue to exist even to this day.

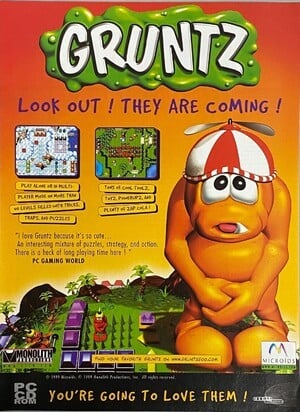

A good example of this is Gruntz, a puzzle strategy game from the studio that has often been compared to Lemmings online, and saw players guiding a bunch of goo-based creatures through various levels from a top-down perspective, fighting, solving puzzles, and collecting tools to help them advance. Released for PCs in 1999, it is a title that is often overlooked in company retrospectives and was pretty much sent out to die upon its original launch. Nevertheless, it still has a fairly active community to this day, with players not only submitting new levels today but also creating fan-made remakes in Unity and Java.

To give you some background, the origin of Gruntz initially began in the mid-to-late '90s with Nick Newhard, the designer and lead programmer of Blood, who had joined Monolith a few years earlier after his own company Q Studios was acquired in 1996.

After finishing development on Blood in 1997, he made a very deliberate decision not to return to lead the development of the game's sequel, Blood II, instead becoming interested in trying out new genres and game ideas. As a result, he ended up attaching himself to a 3D action-adventure project called Draedon, which was in early development at Monolith at the time, which was a game based on the adventures of an old Dungeons and Dragons' character created by one of Monolith's co-founders Garrett Price.

While helping out on Draedon, Newhard would occasionally find himself playing a lot of real-time-strategy games like Command and Conquer and Warcraft 2 and gradually began thinking about making a more approachable version of those games — something that would feature more puzzle-solving elements. So, finding some free time, he eventually wrote up a design document for the idea, with the idea being that this new game would take advantage of the Windows Animation Package 32 engine that had already been used for the 2D platformer Claw (1997) and the Gauntlet-esque Get Medieval (1998).

"I wanted to make something that my wife would enjoy," he tells us. "And I wanted it to be a little bit more puzzling than it was RTS-y, you know? So I just started thinking through this idea of what it would be, what the characters would be like. And I wrote up a pitch. During that time at Monolith, we were all writing up game pitches. We had a ton. Like there was some really groundbreaking stuff that no one ever saw just because the games didn't get made.

"At Monolith, during that time, we were not specifically all about first-person shooters — not yet anyway. We had plenty of other ideas, and Gruntz became one of those. Gruntz was pitched as a game that could fit in a smaller scope and a smaller budget because we didn't have a ton of money at the studio."

According to Newhard, after he finished writing the pitch for what became Gruntz, he ended up putting the concept to one side temporarily, while the team on Draedon continued to discuss that game with an undisclosed publisher. But eventually, the publisher of Draedon ended up pulling out of the deal, effectively killing the project and leaving room for another cheaper title to take its place.

It was at this point that Newhard decided to revisit his pitch for the Gruntz idea, suggesting it as the next project the company should work on. Eventual disagreements, however, over the timeline of the project and other differences in opinion elsewhere meant that Newhard would leave before development on the game had actually started, with the developer (and his wife) being credited in the final release for the initial design concept.

Speaking to Time Extension about these circumstances now, he states, "I felt Gruntz would probably take somewhere between 10 to 12 months to develop. They wanted it in nine. I told them there was no way it was going to get done in nine and I was right. In the long run, I think it took them around 10 months. So I ended up taking a role at Crave Entertainment as a design director and Kevin [Lambert] ended up taking that project on and finishing it. He did a fantastic job making Gruntz, and it was completely different than anything that Monolith had done to date."

Kevin Lambert is a game designer and programmer who was an employee at Monolith between 1995 to 2003. He was one of the very first non-founders to come on board at the studio after it was founded, and had initially joined the company after impressing them with a couple of board-game-style titles he had developed in his spare time.

His very first job at the company was as a designer on Claw (where he had worked on the progression and boss encounters), and had followed this up with an "additional programming" role on Get Medieval, before producing various prototypes for cancelled Monolith titles like Claw 3D and Draedon. Similar to Newhard, he was also interested in exploring a wide range of genres, making him a perfect fit to take over the reins.

As Lambert tells us, "I was really passionate about puzzle games and I was very inspired by games like Lemmings at the time, where you've got to figure out how to get them all to the exit. And so I just started playing around with it and suggested, 'What if we had the guys in here and you can move them around?' And 'What if we made it funny?' Because I always wanted games to be funny and have stupid humor in them. And so I built a little prototype, I showed it to people, and others inside the studio were like, 'This is really good.'"

After showing the prototype around, Lambert ended up leading a small team inside the studio to work on the title, with fellow Claw designer Chris Hewett being brought on board, to help contribute to the overall design, while another one of the studio's co-founders Paul Renault was enlisted elsewhere to help Lambert with the cutscene script and story.

During this process, the team at the studio ended up putting a lot of time into giving the titular Gruntz fun and irreverent personalities to make them stand out from your run-of-the-mill video game characters, having them taunt the player, crack jokes, and occasionally break into song. While in the finished version, most of these jokes are pretty tame, the original plan was for the game to have a slightly edgier tone than what it ended up with.

"Gruntz had very racy dialogue originally," says Lambert. "Like I wrote all of it, and so it had pop culture references, and it had bleeps, it had cursing. It was kind of inspired by South Park humor. Like, 'Screw you guys, I'm going home!' It had kind of that edgy style because I thought that was really funny. And so all the dialogue was very racy and edgy, and there were curse words in it."

At this point in the story, we should probably take the time to go over some of the finer details of the gameplay, as the description we've given so far, we must admit, only really scratches the surface of what the game has to offer.

Gruntz, if you're unfamiliar with it, is essentially divided into two different types of gameplay (quests and battles). Quests see players dropped into one of eight worlds (each divided into multiple levels), with the goal being to lead a colourful army of goo-like monsters around deadly obstacles like spike traps, enemy ambushes, and holes to collect a Warp Stone located somewhere in the stage and offer it up to their king. In order to do this, you will need to take advantage of a bunch of unique toys and gadgets found within each stage to help you progress.

Metal gauntlets, for instance, help you to break rocks blocking your progress, while shovels are useful for filling in holes, and squeaky toys can be placed to distract enemy guards allowing you to sneak by. In addition to this, there is also a straw you can use to suck up dead enemies to save up goo, which can later be used to bake more goo monsters in an oven to help you stand on switches and unlock gates and bridges

The battle mode, on the other hand, is a bit more straightforward, pitting you in a fight to the death against an enemy team on a map of your choosing.

Compared to the other games that Monolith was releasing at the time, Gruntz was a bit of an outlier, with the company having just come off the back of shipping several first-person shooters like Blood, Shogo: Mobile Armor Division, and Blood II. Because of this, the marketing department within the company allegedly didn't know how to position a strategy game in the market, leading to some pretty intense battles between Lambert and those tasked with selling the game about its promotion in the US who were essentially going to position the title as a budget family release with minimal marketing.

"I was literally walking in yelling at the marketing department because I was so unhappy with the way they were taking it," says Lambert. "Our head of marketing yelled so hard at me and said, 'Stop telling me how to do my job!' And I was like 'Well, maybe if you did your job...' This is in the young years where just emotions were flying and you're not mature at all."

The decision to market Gruntz as a family game unfortunately meant that Lambert would have to cut out much of the edgy "South Park"-style dialogue he had originally planned for the game — most of which had already been recorded. Before he did this, though, he tells us he created a backup with the original files that he was hoping to one day release to the community.

"They looked at it and they said, 'We can't sell this. It needs to be more family-friendly if we're going to be able to sell it.' So I was like, 'Really? I gotta take all of it out? Can I at least bleep it out?' They said 'No!' So I had to go through every line and make sure it was okay. What's funny is that I did bleep all the cussing, and I saved off a little secret file that has all the bleeps and the original lines. And I was planning to someday just leak the file and then all you'd have to do is drop it into the Gruntz' folder and it would replace all the lines but I lost it. I don't know where it is. It's probably somewhere in my archives. If I spent like a week and a half digging for it, I could probably find it."

When Gruntz was released in the US, sales of the game reportedly weren't great, while reviews of the title proved to be somewhat middling. IGN's Stephen Butts, for example, awarded it a 6 and called it "a fun game" but stated that "the attempts to make the Gruntz cute or adorable in any way" was totally lost on them, and that it didn't "rise to a smart enough level to provide a challenge to any but the most casual player."

Meanwhile, Gamespot's Ron Dullin awarded the title a respectable 7.4, writing that the game "piles dozens of easy puzzles into each level" and "as a result, it isn't a particularly challenging game, but it is quite a fun way to kill an hour or two at a time."

Its European release, handled by Microids and CDV Software, on the other hand, ended up having slightly more success, with the Portuguese magazine Revista BGamer, for instance, awarding it 91% and praising the game's humour.

"It got released in Europe under a different marketing agency and publisher and it did really well there," says Lambert. "They used to have this running joke on Saturday Night Live about how they love David Hasselhoff in Europe, in Germany. That's what we used to say about Gruntz. They love us in Europe."

On account of the somewhat lukewarm North American reviews and disappointing marketing, you'd be forgiven for thinking that most people simply forgot about Gruntz in the years that followed. However, thanks to the team including level editing tools on the disk, this surprisingly isn't where Gruntz' story ends, with a community eventually forming online around the creation and distribution of custom maps.

Ed "GooRoo" Kivi is a self-described "Gruntzaholic" who has been running a Gruntz fansite and ProBoard forum since December 2003. He first encountered the game a few years after its original release, coming across it after his wife bought the game and ended up putting it to one side. Playing the first few levels, he felt he could create something more challenging, so quickly ended up putting his own level designs to the test.

According to Kivi, the game ended up appealing to him as it didn't feature "unnecessary violence" and wasn't "a "beat 'em, kick 'em, shoot 'em up"-style game, but instead "more like [a top-down version of] the arcade game Mario Bros".

When he originally began running his site in 2003, the game's community was only numbering around a dozen members in total. However, in the following decades, it has since expanded to 368 accounts, with 70 members still on the mailing list to receive new custom-level submissions. In addition to this, he also told us about a couple of Gruntz-based projects that have been produced by members of the community, ranging from Dizgruntled (a Java-based open-source remake of Gruntz) to Gruntz Unityverse (an in-development Unity remake being created with input from fellow Gruntz fans). For Lambert, it's remarkable to see the game still have a life all these years later, and it's something he's 100% in support of.

"I don't know why more game teams don't release modding tools instead of sending them legal notices to shut down what they're doing," he tells us. "After all, some of the best game ideas come from the community."