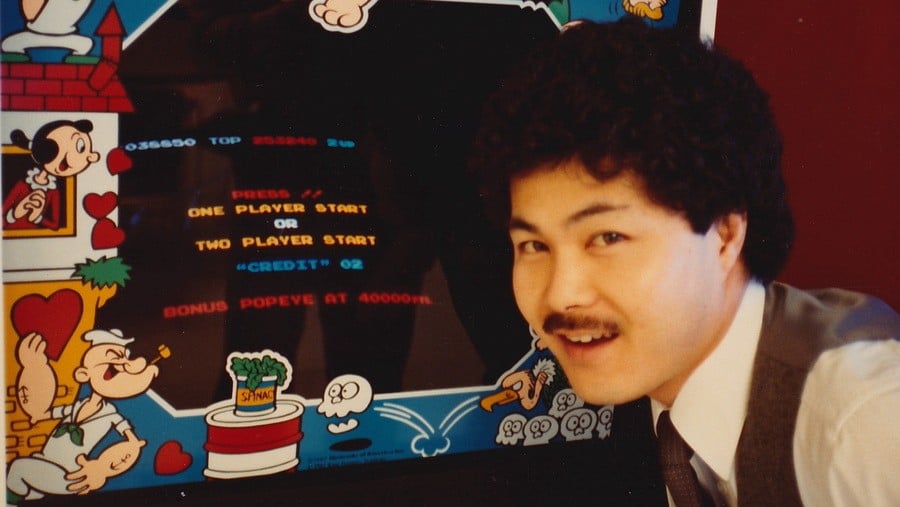

In 1982, Jerry Momoda was playing Donkey Kong at The Spot Tavern in Renton, Washington, following his girlfriend's softball game, when he noticed something unusual.

To the side of him, out of the corner of his eye, watching him closely, was a man in a crisp white dress shirt and tie, who was taking a particular interest in his playing.

Initially shrugging this off, Momoda continued playing, focusing on the small mustachioed plumber he was guiding up the collection of ladders leading up the red zigzagging girders to the damsel-in-distress waiting at the top of the screen, when the man to his side finally broke his silence: "Hey, you’re pretty good. But, how do you know how to do that?"

"Well, it's a simple computer program,” Momoda responded. “When I do this, I can predict how the game will respond."

Following that initial exchange, Momoda got talking to the slightly out-of-place figure, who revealed himself to be Ron Judy, the vice president of marketing at Nintendo of America — a Tukwila-based marketing and distribution outpost for the Japanese developer of Donkey Kong. As he explained, he had stopped by to check in on how the game was performing, and seeing Momoda, felt like he might be able to offer some valuable insights into the secret sauce that had made the title such a hit with players. Because of this, he handed Momoda his card and told him to keep in contact over the following weeks, wanting to hear the player's continued observations about Donkey Kong.

Momoda didn't know it at the time, but this chance encounter would alter the course of his life, setting him on the path to becoming Nintendo's very first "gamesmaster" and kickstarting a 25-plus-year career in the games industry that spanned various companies like Sega, SNK, Atari, and Namco. Looking back on it, it's a remarkable story, and one that is pretty much every kid's dream. So recently, we decided to reach out to Momoda to try and document this journey, charting his course from arcade prodigy to industry veteran.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of Momoda's time at Nintendo, it's worth going back in time a little more to provide you with some context on what he was doing before that fateful first encounter with Ron Judy, and how his love affair with games had originally begun.

Momoda grew up in Bellevue, a suburb of Seattle, Washington, situated across Lake Washington. In the late 1970s, he graduated from the University of Washington, studying business and marketing, and had initially gone to work at the aviation company Boeing following his graduation. Outside of his work and education, though, he had an interest in the arcades — an infatuation which had originally started in the '70s, after encountering Bally's 1971 electromechanical driving game Roadrunner at a Seattle Center arcade.

"Roadrunner was a driving game with 1/64th scale Matchbox-like cars that were physically attached to three separate belts, or lanes if you will, each changing speeds," Momoda explained to us. "It used these belts and a mirror that superimposed your car over these other cars on the belts, and somehow it knew when they collided. When you crashed, you'd get this hard clank of a solenoid, and then it would show your car tumbling upside down.

"That was one of my earliest exposures to gaming, but I also loved a lot of early Atari games, like Night Driver. Night Driver was a first-person driving game that had a black and white XY vector monitor. But still, it just fascinated me at the time because you were able to control what you were doing and seeing on screen".

Over the next few years, as the '70s gave way to the '80s, Momoda continued to stay abreast of the latest arcade advancements, falling in love with a lot of the new titles from Atari, like Atari Football (1978) Battlezone (1980), Missile Command (1980), and Centipede (1981). However, it would be Nintendo's 1981 platformer about an escaped gorilla that would ultimately have the biggest impact on his life and forever alter his career path.

"I first saw Donkey Kong in a bar in my hometown," said Momoda. "I can't explain; something just drew me to it right away. When I first saw the game, I stood there and watched people play, and it just really hooked me. The abstract nature of the game fascinated me. It was unlike any other game I’d played. I wanted to get good at it.

I first saw Donkey Kong in a bar in my hometown. I can't explain; something just drew me to it right away. When I first saw the game, I stood there and watched people play, and it just really hooked me.

“Then, a few months later, I attended my girlfriend’s post-softball game get-together at a place called the Spot Tavern. By then, I had already been playing Donkey Kong a lot. While they were playing pool, I played Donkey Kong. That's where I met Ron Judy."

Over the weeks following Momoda's meeting with the Nintendo of America marketing executive, he kept in touch with Judy, checking in as suggested and chatting over the phone to offer his thoughts on Donkey Kong and what other arcade games he was playing. It was during one of these calls that Judy recommended that the expert gamer head over to Goldie’s, a bar near Seattle's University District, where a new game named Donkey Kong Jr., was currently being tested.

According to Momoda, Goldie’s was a bar that he was already well aware of, having attended the University of Washington, but what he didn't know then was that it was actually a test location for the local coin-operated amusement distributor, Music Vend.

Music Vend also represented other industry manufacturers like Atari, Midway, Sega, Taito, Konami, and pinball makers like Williams and Bally. Their primary business was selling games to operators, but they also operated games in locations like Goldie’s.

Goldie’s was an “A-type” location, having high traffic and a combination of over 50 arcade, pinball, and pool tables. The quarters ($.25 coins) from each game were collected on the same day each week, with the weekly collection at Goldie’s identifying which games were most played by their customers. If a new game was a top earner and continued to be at or near the top for four to six weeks, it would likely be a good return on investment for the operator. But if a game didn’t get played enough and didn’t look like a good return on investment, it would be rotated out of a location and moved to where it might perform better.

Judy asked Momoda to visit Goldie’s to see what he made of Donkey Kong’s sequel, Donkey Kong Jr. Much like their first conversation at the Spot Tavern, Judy, wanted to know Momoda’s thoughts on the game and how he was learning it. Upon playing the game, Momoda's initial impressions were mixed, with his main point of criticism being the way in which it introduced players to its gameplay. He also noted that the original Donkey Kong was still being played a lot. Momoda's first impressions would later confirm that Donkey Kong Jr. wasn’t testing as well as the original, and Nintendo didn’t know why

I liked the game, but [...] it was completely different. I didn't think it onboarded players very well. When I evaluated games, I looked at it from the viewpoint of both a first-time player and expert.

"I liked the game," he told me. "But rather than being similar or an extension of the original game, it was completely different. I didn't think it onboarded players very well. When I evaluated games, I looked at them from the viewpoint of both a first-time player and an expert. In Donkey Kong, the first thing a player does is move the joystick to the right, and Mario moves as instructed. Then, intuitively, you knew you had to jump over and avoid the coming barrels. The path through the 'maze' was clear. But in Donkey Kong Jr., it wasn’t.

"Players could jump to climb vines or move right. It required more thinking, skill, and timing. Players would often 'die' without understanding why and how to avoid making the same mistakes next time. I knew this by witnessing the same confusion among beginners. Too many players made the same mistakes over and over. Clearly, they weren’t understanding what had caused them to die. They became frustrated, quit playing and found a different game to play.”

As he had done with Donkey Kong before, Momoda shared his observations with Judy, with the marketing expert paying a great deal of attention to what the experienced arcade player had to say. Judy then told Momoda that he had a person he wanted him to meet. This person was Minoru Arakawa, the president of Nintendo of America and son-in-law of Nintendo president, Hiroshi Yamauchi.

Momoda's first meeting with Arakawa took place at Goldies, where the Nintendo of America president watched him play and exchanged some words about the game. Struck by the gamer's knowledge and prowess at the game, the Nintendo of America president invited him to Nintendo's HQ, which was then based in a warehouse in Tukwila, Washington, to show the staff how to play the game.

“Entering the factory’s front door the next day, I was surprised that there was maybe less than 300 sq. ft. of office space, room for maybe three desks. Within a large warehouse space stood a lone Donkey Kong Jr. arcade game and a stool. Mr. Arakawa was actually serious the previous day when saying he wanted me to 'show us how to play the game.' Apparently, all work had stopped. All ten employees, plus temporary factory helpers, huddled around the cabinet while I played. I was playing the game flawlessly for over half an hour when Mr. Arakawa broke in and said, 'Okay, you can stop now.' And that was it. I began as a consultant and, within two months, was given a full-time position as Market Research Analyst.

"I remember it was very intimidating because clearly I didn't go to school for this," he continued. "Being of Japanese heritage, I understood the need to be respectful, factual, not overly critical, yet offer opinions of value to R&D. I had no guidelines or examples on how to critique their game design. But Mr. Arakawa was a great resource and offered valuable guidance. To this day, he's the best president I've ever worked for. He was very smart, had great vision, worked really hard, was genuinely kind, and was super nice to all his employees."

Working at Nintendo, Momoda's primary job was to conduct market research, play and test the new games as they were coming in, and keep management informed on new game status, performance, and industry trends. He also reviewed competitive games and identified threats to Nintendo’s current and future offerings.

During this time, gaming and technology experienced tremendous growth with each new title. Competing game companies were very secretive. So, given the confidential nature of his work, his first "office", if you could call it that, was a crudely built “hut”, constructed of stacked Wells Gardner monitor boxes (with monitors inside) that the Nintendo of America manufacturing manager, Don James, had assembled with a forklift to give him some privacy. It was here that he would be able to check out the latest Nintendo prototypes. However, within a year of joining Nintendo, the company relocated from Tukwila to a new facility in the nearby Redmond area of Washington.

"It was near Bellevue," said Momoda. "Not that far from where I grew up. They constructed two brand new twin buildings, each maybe 60,000 sq. ft.. We occupied the first one, and that's where Bruce Lowry, Frank Ballouz, and Bill Cravens joined the company."

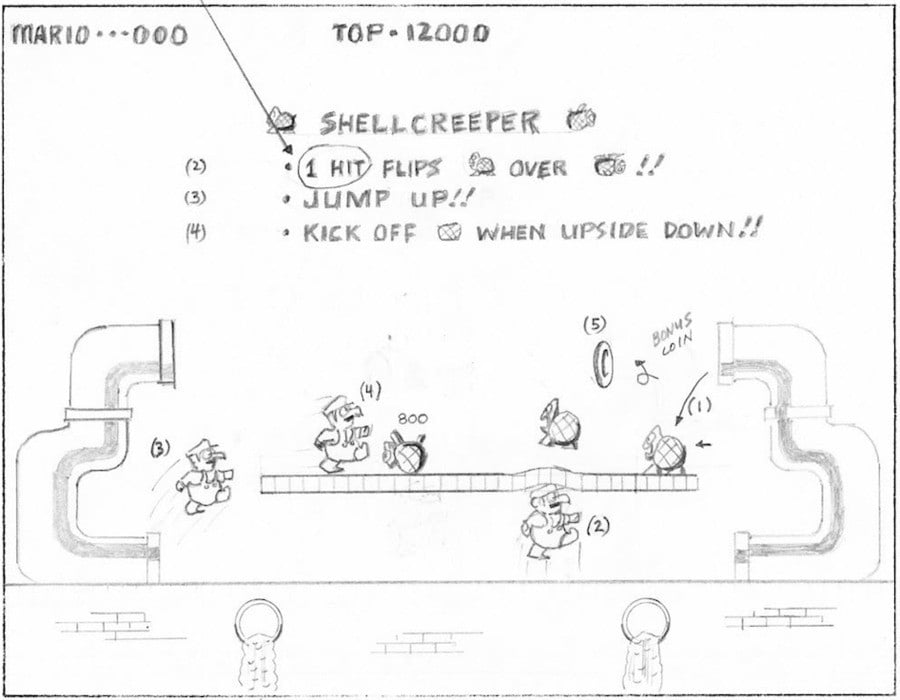

After Donkey Kong Jr., the next slate of projects that Momoda provided feedback for included games like Popeye (1982), Donkey Kong 3 (1983), and Mario Bros. (1983), with the latter in particular impressing the young gamer.

"I loved Mario Bros.," Momoda told me. "And I was stunned that Nintendo did not make a sequel to that game. Super Smash Bros. was similar, but very different. Regarding my early feedback on the game, I thought the onboarding was really important. So that was something that I keyed in on when communicating with Nintendo.

"You'll see in Mario Brothers that there's what’s called an “attract mode” that cycles before coins are inserted. It demonstrates a how-to-play mode and shows some of the higher levels in the game. My design philosophy always held to the old adage, 'easy to learn, hard to master.'"

With each subsequent title, Momoda learned how to offer more to the Nintendo of America machine, providing the company with a US player perspective. This gave him a relatively unique position inside the company as its resident "gamesmaster" — a designation that would lead to other responsibilities further down the line.

Less than one year removed from joining the company, for instance, he would end up finding himself in court representing Nintendo of America as its gaming expert, in the now-famous lawsuit Universal City Studios vs. Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Nintendo of America on August 8, 1983, over a potential trademark infringement involving Donkey Kong. His role: to demonstrate Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. in court, before the judge.

"Within three months after moving to the new Redmond office, Mr. Arakawa said, 'Jerry, Howard Lincoln is going to call you from New York City in about half an hour. Make sure to be at your desk to take the call.'”

"At that time, Howard Lincoln was not yet an employee of Nintendo, but worked for a law firm representing them. In Howard’s call from New York City, he said he wanted me to come out to play Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. in federal court. His assistant made all my travel arrangements, and I was even able to bring my girlfriend with me. My parents hardly knew what a video game was then, so you can imagine how astonished they were to learn I was going to New York City to play video games in federal court.

"Within a few days, we were on a flight to New York City and booked at the Helmsley Palace. Back then, it was a famous posh hotel, located in midtown Manhattan. On the morning of the trial, I met with Howard for breakfast, where he explained what would be happening that day. The skilled trial lawyer, John Kirby, represented Nintendo. The honorable Robert W. Sweet presided over the United States District Court, Southern District of New York, on August 8, 1983.

"In hindsight, it was good that I didn't know much about the case because I wasn't all that nervous. I would have been shaking in my boots if I had known how significant it all was. Think about it. What if Nintendo caved to Universal, as some other companies already had? What if Nintendo lost? We might have never seen another Mario or Donkey Kong game."

Following Nintendo's historic victory over Universal, Momoda returned to Redmond, where he resumed market research duties, evaluating the company's upcoming slate of arcade titles. Out of all of these, the most notable at the time was an exciting new boxing game (then titled Knock Out!!), which had come from Nintendo R&D 3, and had been developed under the supervision of veteran Nintendo game designer and game console designer, Genyo Takeda.

"Genyo Takeda was very nice to me and welcomed my input," Momoda recalled. "Prior to my joining Nintendo, there wasn't a localization effort performed on games from Japan. All printed and on-screen materials were in poorly written English and in my view, not acceptable. I emphasized the need for all this to be written correctly and concise for players to comprehend how to play and for Nintendo to be taken seriously in America."

In Knock Out!!, the idea was that players would take control of an unnamed boxer and work their way up through the ranks, with the fighting being shown via a camera located behind the character. However, this approach presented some issues with playability, as the player’s character obscured the opponent's body, making it difficult for the player to read and react. As a result, the designers chose to switch the main character's solid shape for a transparent wireframe body, for which Momoda provided input on the optimum viewpoint.

In October 1983, Knock Out!! was shown only to distributors at the Amusement and Music Operators Show in New Orleans. In attendance from Japan was a young Shigeru Miyamoto, Punch-Out designer Genyo Takeda, and three team members who traveled to the States to witness the first impressions by Nintendo of America’s distributors..

"Knock Out was well received by our distributors," said Momoda. "Using a wireframe fighter, it presented a novel 3D look on a 2D display, and the game's stacked two-monitor design was a big hit too. Both figuratively and physically. Knowing our distributors, I often gave demonstrations and fielded questions on test earnings.

In the creation of the advertising sellsheet, Momoda submitted a sketch of a tall Punch-Out cabinet (w/arms), standing hand raised by a referee, positioned over a knocked out fighter on the mat. Nintendo’s advertising manager liked it, and a local boxing club was chosen as the location for a photoshoot. Apart from the fallen boxer and referee, everyone in the shoot was a Nintendo employee or one of Momoda’s friends.

“All these years later, I still shake my head in astonishment at all the different sides of the business I got to participate in," he said. "This would never happen today."

In February 1984, at the first-ever ASI Show, Knock Out!! made its official debut under a slightly different name, Punch Out!! Nintendo arranged for the former WBC Heavyweight champion boxer, Larry Holmes, to help promote Punch-Out!! and draw people to Nintendo's booth.

"It was Larry Holmes, not Mike Tyson, who was involved in the initial promotion of Punch-Out!!," said Momoda. "He served as our boxing and celebrity representative in the booth at the show, attracting so many people. He signed autographs and took pictures with showgoers. He and his entourage worked great with our staff and show attendees."

Something worth highlighting is Punch Out!! wasn't the only new arcade attraction Nintendo would show in 1984. In addition to Punch Out!!'s boxing-based gameplay, the company would also debut the Nintendo VS. System in the country that very same year.

The Nintendo VS. System (or VS. System for short) had, just like Punch Out!!, been unveiled at the ASI event in February 1984. It was designed to cater to the arcade industry's demand for lower-priced games. It was available in three configurations — an upright two-screen (side by side) DualSystem cabinet, and a sit-down, tent-styled, two-screen (across) DualSystem setup — prioritizing a multiplayer ”versus” style experience, with the DualSystem variants also being fitted with a pair of dual-screen monitors to allow opposing players their own individual screen to play on. Later on, a single-screen upright version named the UniSystem was also released.

"The VS. System was revolutionary in that it was the first game to offer two or four-player head-to-head competition on separate screens," said Momoda. 'In 1984, at another university area arcade named Arnold’s, I organized what might be the first ever competitive head-to-head video game tournament. It was called the “VS. Open”, featuring the game, VS. Tennis. The operator liked the large crowds, and lots of players competed. We gave out t-shirts and prizes to the players. It was such a hit that I created a tournament kit for Nintendo’s game operators. A tent-style card further promoted the different ways the game could be played.

"One of the attractive features of the machine for arcade operators was the ability to quickly and easily switch out games. Because the games were initially designed for the Famicom console sold in Japan, they featured less sophisticated graphics than Nintendo's other arcade offerings, which had been built exclusively for the arcades."

Momoda would play a big role in the launch of several VS. titles in the arcades (including VS. Duck Hunt, VS. Hogan’s Alley, VS. Tennis, VS. Golf, VS. Baseball, VS. Balloon Fight, VS. Ice Climber, and VS. Wrecking Crew) — all of which were released between 1984 and 1985. As he explained to us, though, he had some reservations about what these titles could mean for the future of Nintendo's arcade output, with these games looking a far cry from titles like Punch Out!! and essentially being used to pave the way for Nintendo of America's own console (which would debut the following year under the name, the Nintendo Entertainment System).

For Momoda, he dreamed of working in product development to launch more technically advanced games, and this was definitely not that. As a result, he made the difficult decision in 1985 to leave Nintendo, joining the company's rival, the arcade manufacturer Sega Enterprises Inc., to see if he could fulfill this dream elsewhere.

"My excitement at working at Nintendo was about making games," he told us. "In each new game before the VS. System, there was a constant improvement in hardware, chip technology, game graphics, game controls, and gameplay. I wanted to work on the bleeding edge of technology. To the gamer in me, the VS. System/NES was going backward. They were good games, and the NES was hugely successful, but it just wasn't the direction I wanted to pursue in gaming. That’s mainly why I accepted the offer from Sega."

For Momoda, working at Sega sounded like an exciting opportunity on paper. Officially, he would become a product manager. Sega was then a top arcade company. It was an opportunity to work on groundbreaking coin-ops like Zaxxon and use the experience and knowledge that he had acquired. But this didn't exactly go to plan, however, with Momoda quickly realizing that Sega in Japan was far less open to collaborating on design with its overseas partners than Nintendo.

"When I look back on it, Sega was not a great step for me," he revealed to us. "I wish it hadn't happened. At Nintendo, I was encouraged to contribute, but Sega operated differently. I would give my feedback, but it often fell on deaf ears.

In total, Momoda spent two years at Sega working as a product manager for the company, helping to launch games like Hang-On, Out Run, Enduro Racer, and Choplifter in the States. One benefit of joining Sega was that he moved to the California Bay Area’s Silicon Valley, where other game companies had offices.

Following Sega, Momoda joined another famous company, Atari Games, based in Milpitas, California, in 1987. This was something of a dream-come-true for the arcade fan who had spent countless hours playing Atari arcade games and was now getting to work alongside his heroes.

"I couldn't believe it," Momoda told us. "I was actually working with a lot of the guys who actually created those games. I was starstruck at first — 'Holy cow. These are the guys who made those games.' A lot of them I still know to this day. In fact, a couple of weeks ago, we had a get-together at Ed Rotberg’s. He's one of Atari's famous designers who designed and programmed Battlezone, Blasteroids, S.T.U.N. Runner, and had his hand in countless other games, also. To name drop a few others attending, there was Ed Logg (Asteroids, Centipede, Gauntlet), Rich Adam (Missile Command, Gravitar), John Salwitz and Dave Ralston (720, Paperboy, Cyberball), and Dennis Harper (Toobin’). A video game Hall of Fame.

At Atari, Momoda contributed to the launch of 17 games, including the likes of Cyberball, Toobin', Pit Fighter, S.T.U.N. Runner, R.B.I Baseball, and Dragon Spirit. His responsibilities were to conduct market research, carry out field tests, provide product marketing, and offer design feedback, with the ultimate goal being to ensure that whatever game was being played, it made a good first impression on the player. This was a job that he was particularly adept at, having already acquired a ton of experience and knowledge in this field. At this time, Atari was owned by Namco. Having worked for other Japanese companies, he did most of the product management and localization work for Namco games. Atari would end up being his place of work for the next six years. But it wasn’t all roses at Atari Games. Momoda felt the company had aged and was no longer relating to an evolving player base. Specifically, the growing fighting game genre.

After Namco sold Atari Games and opened its own office, he accepted an offer to become the product manager for the North American subsidiary of Namco in 1993.

This is an area of his career we've touched on before, but essentially, what you need to know is that while he was at Namco, he was integral in suggesting project ideas and case studies — something that would help get projects like Tekken and Time Crisis off the ground.

"What made Namco fantastic was that they were open to taking outside concepts and making them their own," said Momoda. "If I could plant a seed in someone's head that could potentially spawn into something greater, and they could take ownership, they’d probably work harder on it. For Tekken, I wrote a business case and traveled to Namco HQ in Tokyo, advocating for Namco to create a fighting game to rival the likes of Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter. I planted the basic seeds of what I believed a fighting game needed to succeed in the U.S., and they ran with it. I worked on that project daily from the US. It was so much fun. They kept me involved in core decisions affecting the game. I worked on Tekken 1, 2, and 3. Namco’s designers are among the best. It was phenomenal how that game came together."

Today, Momoda has officially retired from the games industry and mostly spends his time snow skiing in the winter and golfing in the summer.. However, he still has a huge appreciation of gaming, including sim racing, having his own dedicated setup that allows him to appreciate the many advances in gaming over the years. Reflecting on his career in the modern day, he still looks back fondly on the people he was able to meet and work alongside. He especially remembers Nintendo and the late Ron Judy, who sadly passed in 2024, the person who originally set him on this wild adventure all those years ago.

If you're interested in learning more about Momoda's career, we recommend visiting his website, where you'll find a ton of firsthand recollections about his time in the business and the methodologies he developed for assessing classic arcade games.