The launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in North America is one of gaming's greatest success stories.

At the time of its original test market release in October 1985, the market for video game consoles in North America was considered to be dead, with memories still strong among retailers of the video game crash that had occurred just two years prior.

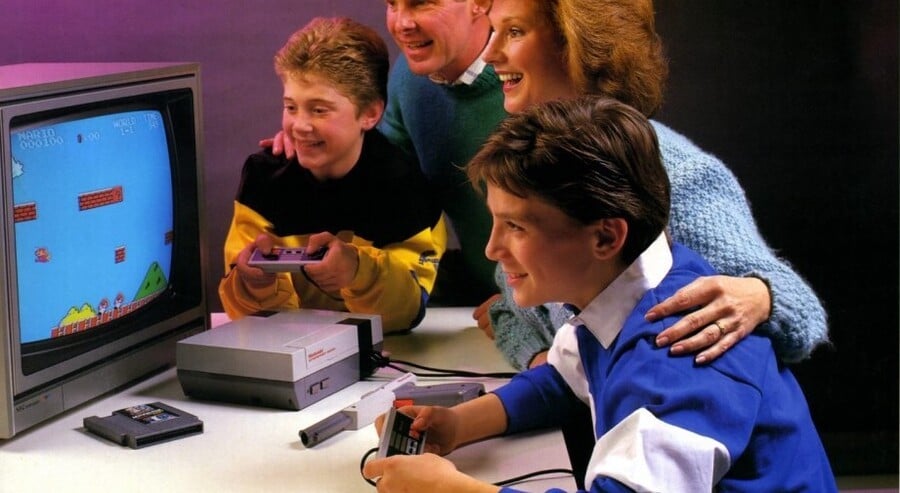

As a result, no one was particularly confident whether a new video game console could actually catch on or not, or if its creators, Nintendo, were simply setting themselves on a collision course with failure. Backed, however, by a strong marketing push, great games, and some interesting at-home gimmicks like R.O.B the Robot and NES Zapper, the console ended up proving a lot of the skeptics wrong over the next 14 months, going on to become one of the must-have "toys" of Christmas 1986 and successfully helping to put video game consoles back in the spotlight.

Looking back now, there are a lot of people who were responsible for this success, with the Nintendo of America vice president of sales, Bruce Lowry, being one such person who is counted among them. He had a huge role in making suggestions for how to position a video game console in a market where "video game" had seemingly become a dirty word, and was also integral for getting the game into stores at the time, winning over retailers who had previously lost a lot of money on Atari.

Recently, we interviewed Lowry about his role in the Nintendo Entertainment System's success to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the console's initial release, and couldn't resist asking him some other questions about his storied career. That's because Lowry wasn't just responsible for helping to launch the Nintendo Entertainment System, but also had a hand in establishing Sega of America and attempting to take the fight to Nintendo with the Sega Master System. You can read our conversation with Lowry below (slightly edited and condensed for clarity and length).

Time Extension: How did you end up working for Nintendo? I've heard that before you got the job at Nintendo, you were working at Pioneer, but not on anything gaming-related. How did you end up making that jump to working in games?

Lowry: I had been working at a division of Pioneer Electronics, called Phase Linear, which was in commercial audio, and I was the vice president of sales. So, any concert you were at, nine times out of 10, all the major groups were using our amplifiers. I was having a wonderful time; it was a great job. And then Pioneer sold the division to a company in Chicago, and I had to move.

I was raising my two sons by myself at that time; they were not really excited about leaving Seattle, and it just so happened that I got a phone call from my recruiting firm on the day I was going to Chicago. It said, 'There's this new company starting up called Nintendo'; I couldn't even pronounce the name. It's funny, it sounds so generic now. But back then, over the phone, I was like 'Is it Nint-ento?'

Anyhow, I met with Arakawa, who was the president, and Ron Judy, who was vice president. And we met for maybe an hour at the airport. Well, at the end of that hour, I was not leaving for Chicago. They had convinced me that I should come to work for Nintendo. I still remember to this day, I said, 'So what are we going to be selling?' And they said, 'We have this new handheld called the Game & Watch', but we're also planning to launch our own video game system.'

When they told me that, I was kind of questioning my decision to join them because of the video game crash in '83, but it was such a dynamic group of people — there were only about 10 of us at the time.

Time Extension: Besides Minoru Arakawa and Ron Judy, who else was there?

Lowry: Al Stone was there. Also, Don James. And there were a couple of design people and engineers. It was a very small company, but we had great hopes that it would turn into something.

Ron Judy and Al Stone had been old friends from university. Ron had been a vice president at Chase Bank in New York, and Al had been vice president of [a shipping company]. They had set up a company together called Far East Video to bring arcade games to the US from Japan, which is how they initially came into contact with Nintendo.

The story goes that Al was over in Japan and he saw these Nintendo arcade games and thought, 'Maybe we can bring them to the U.S.' So he convinced this tiny Japanese company that they were experts in the area, and Nintendo ended up buying them out. So I ended up working with all of them in a little office in South Seattle, down by the airport, where we all became good friends.

Time Extension: When you arrived at Nintendo of America, what discussions were Nintendo having about entering the console market? I remember hearing from Coleco's Bert Reiner that Coleco had actually met with Nintendo of Japan, with the idea of Nintendo distributing the ColecoVision in Japan. What discussions do you remember hearing at the time?

Lowry: There are two things that I can remember [before the launch of the NES]. One was Coleco. But what Coleco really wanted to do, if my memory serves me right, is Coleco wanted to have Nintendo games on the ColecoVision machine. That was their big push.

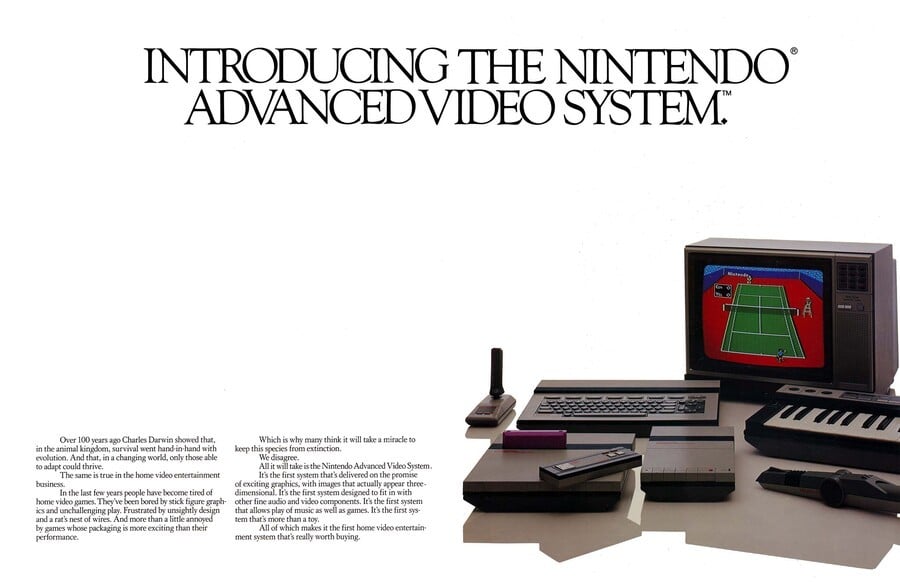

At the same time, though, Atari was making a play to launch the Nintendo Advanced Video System (AVS), which Nintendo had already started to develop. They wanted to put it out there under the Atari name. But they then backed away from the idea because the industry was dying, so their belief was, 'Why invest in something like that?'

Time Extension: I was going to ask you about the Advanced Video System (AVS). This was the machine that was shown off at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in 1985, right? Before the release of the NES.

Lowry: Yeah, so the AVS was the precursor to the NES, and was also based off the Nintendo Family Computer.

So, the Nintendo Famicom — you've probably seen what it looked like — it was like a little white toy. And so when they said, 'This is what we're going to bring over to the U .S,' they also said, 'We probably need to change the look of it.' That initial redesign came out of Kyoto*, but the final NES design was designed by our team in Seattle. The problem was we weren't sure how we were going to launch it, and a lot of that fell on me, because of my background in sales. One of the discussions I remember having was about the look of the product.

Something that I had noticed, thanks to my background coming out of Pioneer Electronics, was that everybody at that time was really into having their own rack of audio equipment. So I had commented, 'We shouldn't make it look like a toy like the ColecoVision or the Intellivision; we should make it actually look like a device that you would have with your other electronic systems.' And I believe that was one of the reasons why Japan eventually decided to let us redesign the look of it in the U.S.

*[Editor's Note: It seems Lowry could be misremembering things here, as the Video Game History Foundation's conversations with Nintendo's industrial designer Lance Barr suggest he was responsible for the AVS design, not Nintendo Co., Ltd in Japan.]

Time Extension: So that explains why the NES ended up looking like a video cassette recorder.

Lowry: That's right. It was because we wanted to make it look more like a piece of entertainment equipment, which would fit alongside your other equipment at home. So it kind of had that look of a VCR, with how it was loaded and everything. But we realised that it still had to look like it'd be fun to use too; that any age could use it.

That's because parents who had exotic audio equipment in their homes usually didn't allow their kids to touch it. So it had to look like a piece of electronic equipment, but equipment that all ages could use. The name was really critical too, because you didn't want to use the words 'video game' anywhere near it. That was the worst thing we could have put on it at the time; that would have killed it. I remember everyone was in the conference room, and I said to them, 'We can't go that way. We can't say anything about it being a video game console.'

The question, then, was how are we going to sell a video game if it isn't called a video game console? And that's where we came up with this idea of taking the system from the AVS and pairing it with the idea of entertainment: the Nintendo Entertainment System. Once we hit on that, it all started to make sense because we could have all these different things that we could add to it, like R.O.B. the Robot, which I never particularly liked, but felt was pretty unique and different for the time.

As for the Zapper, I mean, originally, it was gonna be called a light gun. But something was eating at me a little bit because, at that time, the arcades were getting a very bad reputation. One of the incidents I remember hearing about was that police had gone into an arcade and a kid pointed an arcade gun at them, and they [mistook it for a real weapon]. That made everybody change their guns to a bright orange, red, or yellow, [including us].

Because of that, we weren't sure of the name either. So we decided that we were going to do a focus group, which we did in Paramus, New Jersey, where Ron and I set up with a great company. They brought in about 20 or 30 housewives who have children, and the person leading the focus group told them all about the Nintendo light gun, Duck Hunt, and all these other great things, and about a third of the women got up and walked out. And the others were all saying, 'No guns are coming in my house.'

Immediately after, we had another group come in, and all we did was change the name to the Zapper, but this time the results were the exact opposite; they all thought it was great. So that one little focus group could have had a big impact on our success.

Time Extension: Were there any reservations on the part of retailers in stocking a new video game console, given that a lot of them had lost money on the Atari 2600? Do you have any interesting stories about trying to get retailers on board?

Lowry: The first sales call that I had, we went to a company called Woolworth's, which had a chain that was like Kmart called Woolco, in New York.

I went through the whole presentation about the NES and why they should buy it, and the buyer just looked at me and didn't say anything. When I was done, I asked him, 'What do you think?' And he said, 'Well, there's good news and bad news.' He told me, 'The bad news is I want to throw you out the window. I asked, 'What's the good news?' and he said, 'The good news is you won't feel it when you hit the ground from the 23rd floor.' He was laughing, but he was also serious. He told me 'Get out of here! We want nothing to do with it.'

I walked out of there, and the salesperson who was with me panicked. I just told them, 'Don't panic. They just don't understand. We've got to make sure our message is right.' And so the next person we called on was Toys 'R' Us. Howard Moore, the executive vice president at Toys 'R' Us, understood the value of it right away, and he also understood our pricing philosophy. We were not going to have people just discounting it. I had told them, 'You started selling all this Atari stuff at pennies on the dollar. We don't want to get into all that. It's time for you to make a profit. And we want to make a profit too.'

Besides Woolco, I'm confident everybody else took it, but I will say there was one interesting presentation I was supposed to do with Sears in Chicago, where I was unable to make it because my grandmother had passed away. I asked Ron Judy and Arakawa to do the presentation for me, and I forgot to order a TV. So they had to go to make the presentation without one. The buyer called me, and he couldn't stop laughing. Apparently, Arakawa had proceeded to show how Duck Hunt worked by flapping his arms and telling Ron to shoot him.

Time Extension: My impression of the launch was that it was quite staggered. Do you have any more info about the initial October 1985 release?

Lowry: So, originally, we were not going to launch it in New York. Ron and I had decided we were going to do the launch in Kentucky instead. Because if we did it wrong, we could go back and revamp it, because it was a little state. Almost like a test market. That was our whole plan.

We were at the CES show, where we finally showed the product for the first time, and Yamauchi was there, and so he had Arakawa, me, and Ron, and then his daughter (who was married to Arakawa) translating the meeting. We had our plans all set up for launching in Kentucky. We knew how we were going to do this; it's a great plan. And he proceeds to tell us we're not launching in Kentucky, we're launching in New York, because that's where everything happens. Ron looked at me. I looked at him. Even Arakawa looked at us.

Arakawa said something to Yamauchi in Japanese that we didn't understand, but we did understand his reply, 'No, no, New York.' So we had to rechange the whole game plan of what we were going to do and immediately shift gears. It was difficult to have that dumped on us. But after we left and got a few blocks away, we said, 'Okay, let's do it!'

Time Extension: We've talked about the actual design of the console. Do you have any insights into the NES packaging at all? The first group of NES games came in black packaging that had pixel art of the game in the middle. Do you remember how that came about?

Lowry: We wanted to put an image of the game on the box exactly as it was in the game. Because if you recall, in those Atari days, they had great pictures on the box, but it was always stick figures when you put it in the machine. And that upset people. People were saying, 'That isn't fair. ' Our approach was, 'You've seen this game in the arcades, it'll be just the same on your TV at home.' We pitched that very hard, and looking back in hindsight, it seems like a great strategy. But at the time, it just felt like a logical decision.

Time Extension: Do you happen to remember who did the manuals for the games? I was speaking to an ex-Nintendo staff member recently, who told me that the reason Koopa became Bowser and Princess Peach became Princess Toadstool in the Western version of Super Mario Bros was because it was an external marketing company doing the game's booklets. Is that correct?

Lowry: A lot of the manuals and stuff were actually provided by Nintendo of Japan. They would send over the manual, basically, and they would try to translate it, and then we would go through it and actually translate it. We had a marketing team inside who would make the necessary changes to it.

If I can digress just a little to talk about the software, I have a few stories I can share. When we first allowed third parties to do games for the system, I remember a friend of mine, Trip Hawkins (the founder of EA) said, 'Boy, they're really tough with what they're doing over there.' I said, 'Well, yeah, the quality of the game has to meet a certain standard.'

Basically, whenever you submitted your game to Nintendo, they not only analyzed it for bugs, but also for its play value and what was shown in it. Yamauchi had always said from day one, 'Our games will always be games that people of all ages can play. There won't be violence. There won't be shooting and killing. There won't be all this kind of stuff. He was adamant about that.'

It didn't always work out, though. Our first year, the worst game we released was Donkey Kong Jr. Math; it was the worst game we ever sold. I think that was one game that slipped through. It was essentially Donkey Kong Jr. and Donkey Kong, but you had to swing across and get a number, bring it back, get another number, bring it back. We thought it'd be great for kids' education, but we couldn't give it away.

Time Extension: In 1986, you left Nintendo and helped in founding Sega of America. Why did you decide to leave Nintendo? It seemed like you were fairly happy there.

Lowry: To this day, I look at it as probably the biggest mistake I ever made. It was a difficult decision. I had been pursued by Nakayama, the Japanese president of Sega, because they wanted to come to the U.S. Also, I had gotten married, and my wife didn't necessarily like Seattle that much.

So they had been approaching me for like a year and a half, and I would always just say, 'No'. But, finally, he hit me with something that I thought was kind of an interesting question: 'Do you think you could do it again, or were you just lucky?' That kind of ate at me a little bit. And I said, 'Well, let's give it a try.'

It was not an easy decision. Like I say, to this day, I wish I had never made that decision. That will always haunt me that I made it. But I moved down to San Francisco and was basically a company of one person. Sega already had the arcade division in San Jose, but I became the founder and president of Sega of America. I hired everybody, set everything up, and it was ready to go and attack Nintendo. And it was basically the same marketing plan I'd used at Nintendo.

Time Extension: How soon after you moved to Sega did conversations about bringing the Master System over to North America start? Was it immediately?

Lowry: Yeah, so what was interesting with the Master System was it was the better system, but when we sat down, I told them, 'You've got to redesign it.' I was over there for like a month in Japan, and we went through all these different designs, everything to get it to compete against Nintendo, and my marketing guy, Bob Harris, also came up with its new name, the Master System.

I remember I was in Japan with Bob and Okawa-san, who was the Sega chairman and a very wealthy individual, met us at a hotel. Anyhow, he asked us, 'Why did you call it a Master System?' Well, Bob had done martial arts for a long time, and he just said, 'In martial arts, you always want to achieve being the master'. Okawa bowed and replied through his translator, 'Very smart!'

Later on, we got ready to launch it, and like I said, I've read some stuff on Wikipedia about how we had no success at all and this, that, and the other. I don't know where they got that information, because we had Sega in every store Nintendo was in within the first six months — it was not hard for me to do because I knew all the buyers. So we were already side by side with Nintendo. That's why we made the Sega box white, because we knew the Nintendo box was black.

Time Extension: What did you think of that relationship between Sega and Tonka? Was it a move you approved of at the time?

Lowry: I had full distribution of the Sega Master System and Sega Base System in the US and Europe before Sega Japan decided to use Tonka Toys. I strongly disagreed with this move, and it was why I decided to leave Sega. It turned out that I was correct, and Sega later terminated the relationship.

The problem with Sega versus Nintendo, though, was that Sega had a lot of internal conflicts going on. There were huge power plays, and you were constantly having to fend this off or fend that off. It wasn't a long-term environment for people. You could just tell. And I had trouble keeping some good people.

To explain how I came back to Nintendo, I was getting ready to leave Sega, and I was over in Venice with my wife for a vacation, and I remember saying, 'I wonder what Ron Judy's doing?' because he was over in Paris. I called Ron, and I met with him in Venice. Ron said, 'Look, I'm trying to branch into Europe with Nintendo, and it's not working; Sega's crushing us here,' which I already knew was because we had launched the Master System simultaneously in the US and Europe. He said, 'It's time to come back. Stop this Sega nonsense. You can live in England and set up the UK operations.' And I did.

Time Extension: What were the things that you identified that Nintendo was doing wrong in Europe?

Lowry: They were trying to use a toy company. They were using Mattel in the UK to sell the NES, and as far as Mattel was concerned, this was an afterthought. In other words, after we've sold everything else that Mattel makes, then we'll try and sell the NES. That was basically their philosophy. They're not in the video game business; they're in the toy business.

It was 'We've got to sell Barbie, and Sega owns the market anyhow, so why would we even try?' It was that kind of situation. So I said to Ron, 'We've got to dismiss Mattel', which it turns out they were excited about, because they were sitting on $5.5 million of inventory in their warehouse. Ron was the finance genius, and I was the sales and marketing guy, and we ended up buying their inventory. And they would ship for us. They'd be our distribution center for us.

Time Extension: Did you find it slightly bewildering going into a market where microcomputers were so popular and people seemed to have a preference for more open-ended systems? Or was all of that just a completely different kind of market that didn't come into consideration?

Lowry: We were aware of it, but I feel we presented it in such a way that this was unique; this is like another class.

Time Extension: Something that I've seen referred to in the past regarding the NES in the UK is that a company called San Serif released a popular NES bundle featuring Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles, which seemed to really help the console in the region. I'm wondering, did you have any involvement in that coming bout? Or was that simply something a sub-distributor put together?

Lowry: It was something the distributor put together. That was just a one-off kind of thing. That's the hardest part about business in Europe is you're not dealing with different states, you're dealing with different countries. And there are certain things you can do in one country you can't do in another country, whereas in the States, you can do the same thing in every state. You have the language situations, and it was always a little extra effort to work out, 'How do you present here? Or how do you present here?'

I worked at Nintendo UK for about four years, and then it was time to come back to the U.S, and that's when I took over running GameTek, which was in real trouble at the time, and I spent about three years turning it around. Then we were approached to take it public on the NASDAQ, which I did. I did an IPO.

Time Extension: Thanks again for giving up your time to speak to us. It's been fantastic to hear your memories of Sega and Nintendo, and I hope our readers find it just as interesting as we have.

If you happen to be in Portland later this month at the Portland Retro Game Expo (October 17th to October 19th), Bruce Lowry will be joining fellow former Nintendo employees Gail Tilden and Lance Barr to talk about the launch of the NES live and in person on Saturday, October 18th.