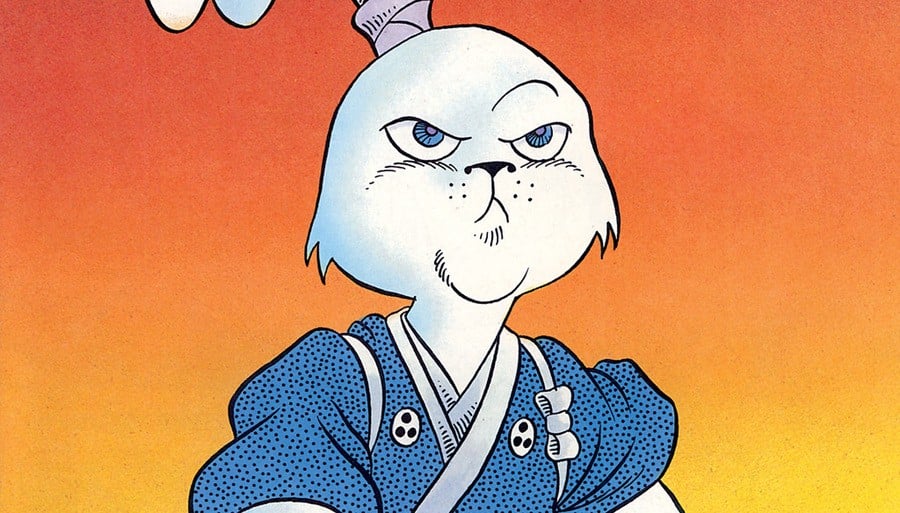

Created by Japanese-born American comic book artist Stan Sakai, Usagi Yojimbo is a cult comic creation that originally debuted all the way back in 1984.

First featured as a comic strip in Steve Gallacci's anthology Albedo Anthropomorphics, and later in issues of the Fantagraphics Books' publication Critters, it also went on to receive its very own comic book in 1987. These all followed the continuing adventures of Miyamoto Usagi, a samurai rabbit, as he made a pilgrimage across Edo-period Japan, encountering bounty hunters, ninja clans, and various monsters from Japanese folklore.

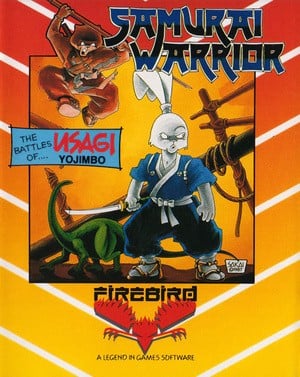

Despite never quite taking off in the same way as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird's creation which also debuted in 1984 and similarly featured anthropomorphic animals wielding Japanese-inspired style weapons), it has gone on to become a well-loved and well-respected comic since its original release and has also occasionally been the subject of adaptation into other mediums. This includes being turned into a popular computer game from the Australian company Beam Software (The Hobbit, The Way of the Exploding Fist, Shadowrun), for the Commodore 64.

Released in 1988, Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo is a sidescrolling adventure game that was created by a small team inside Beam comprised of the designer Pauli Kidd, the programmer Doug Palmer, the artist Russel Comte, and the composer Neil Brennan. It saw players take control of Miyamoto Usagi, the ronin rabbit from Sakai's comics, with the main premise being to guide the character through ambushes, monster dens, and other dangerous scenarios, on a quest to save a young daimyo Lord Noriyuki from a gang of kidnappers.

Described by reviewers at the time as "a thoroughly entertaining" title and "a cut above so many other martial arts games", it later went on to become a success for the Aussie video game developer and still seems to occupy a special place in a lot of player's memories. So, here at Time Extension, we wanted to reach out to those who worked on the project (including designer Pauli Kidd and programmer Doug Palmer) to learn more about its development. Along the way, we ended up talking to the team about the game's design and some of the exciting content that sadly didn't make the cut. But first, we were curious how the team settled upon creating a Usagi Yojimbo game in the first place.

Reflecting on the origins of the project, Kidd tells Time Extension, "Stan Sakai was a good friend of mine. I was deeply involved in the B&W alternative comics world at the time, having published the role-playing game Albedo. I had met Stan at a CAPS (Comics Art Professionals Society) meeting, had seen him at art parties in LA, and had the pleasure of hanging out with him in his home. I saw a big part of my work as a designer at Beam to be designing and proposing original work. So I put together a proposal for 'Usagi' and pushed it to the higher-ups."

The programmer Doug Palmer adds, "I think Fred Milgrom (the founder of Melbourne House and Beam Software) also noticed that everyone would read Usagi when a new one came out. It had originally appeared in Albedo and Critters. Albedo was the initial draw and was good enough that Pauli designed and produced a paper role-playing game based on it. However, from that, I and others started getting the Usagi-only comic when it came out."

After the project was officially given the greenlight inside Beam, the first aspect of the game that the team tried to nail down was the swordplay. Much like in the comics, Usagi would also carry around a samurai sword in the game as his primary means of attack, with the team hoping to create a more sophisticated combat system that mirrored the drama and style of the epic battles depicted in Sakai's work.

As a result, a significant amount of time was paid to making sure the fighting had a bit more nuance than your typical one-button, one-outcome hack-and-slash titles. In the end, the system they came up with gave players a few more options, allowing them to parry, perform sideswipes, and unleash devastating overhead attacks, depending on their inputs.

"The sword fighting had to be at its heart," says Kidd. "So a lot of development at the start went into trying to make a combat game that would be unique, fun - and have the particular style of the comic. As someone who has a lot of [knowledge of] Japanese sword styles, I can tell you that Stan's vision of people running at each other is fun but 'unique!'"

If you've played Usagi Yojimbo in the past, you'll already know that sword fighting isn't the only form of activity that's featured in the game, with the player being able to switch between two different types of control modes: peaceful and violent.

When players first gain control of Usagi, his sword will be originally sheathed at his side, with the character walking more slowly and being limited to non-lethal interactions. But once he takes out his blade, he will be allowed to attack, with the character being able to move more nimbly across the screen and jump much farther than before (a faster song will also play to indicate this change).

Whereas in other games of the period, players were typically encouraged to run through levels, sword-drawn, killing everything in sight, Usagi Yojimbo instead discourages this kind of approach, with players not just encountering ninja clans, bounty hunters, and creatures as they travel through the game's world, but travelling priests, nobility, and peasants too. Attacking these will reduce your karma (an additional attribute displayed in the upper right-hand corner of the screen), with Usagi performing seppuku (a form of Japanese ritual suicide) if this value falls below zero.

This is what makes Usagi Yojimbo so unique, as the game encourages players to think about when they should take out their weapon.

"I wanted a game that could fool you and possibly tempt you into failing," says Kidd, talking about why they decided to take this approach. "A game that would make you think! The usual 'kill everything' style makes for a dull game, and again - the samurai ethos of honour and karma is central to the comic. So I always tried to preserve the core message of the story!"

Speaking to Retro Gamer back in 2006 (issue 29), Palmer told the magazine, "Apart from the general desire to reflect the way of the samurai, Pauli and I were role-players and getting a bit sick of the use-a-bigger-gun approach to role-playing. Pauli developed this theme further in his paper RPGs, such as Albedo and Lace & Steel, where there are sophisticated mechanics for handling personal relationships."

Because of this desire to avoid unnecessary violence, players are encouraged to consider how they respond to the world around them, with the most common action being to bow to non-violent characters you meet on the path, such as priests.

This behaviour will occasionally reveal some words of wisdom, with these ranging from helpful (if slightly obvious) warnings that the player is about to be ambushed on the road ahead to more ambiguous statements, borrowed from the book "Zen Flesh, Zen Bones". This includes the Zen Koan "If you meet Buddha on the road, kill him" — a phrase attributed online to the Ninth-century Chinese Buddhist monk Linji Yixuan that was sure to stump younger players who would no doubt take the instruction literally.

Apart from bowing, there are also a few other activities players can perform while in peaceful mode, with those in control being able to use money collected on the path to gamble, purchase food, and donate money to priests and peasants (offering ryo to nobles you meet on the road will cause their guards to attack).

Interestingly, speaking to both Kidd and Palmer while looking into the game, it is clear that there were a lot of features planned in the game's original script that were eventually cut from the final release when trying to squeeze it to fit onto a C64. In the past, Palmer, for instance, has revealed that Russel Comte had created some art for the Mogura Clan (a group of ninja moles that debuted in Critters issue 10) that were set to appear as additional enemies on the road and that there were other events the player would encounter. Pauli Kidd gave us some insight into these.

"There were supposed to be many other things," she states. "Saving riders dragged by horses, escorting rescued hostages, and seeing their safe return... There were lots more branching pathways in the design, but they were all cut. This included some landscapes that would have been amazing - and problems such as tidal areas, avalanche-prone snowy mountain paths, and haunted castles complete with ghosts (and ways of solving the hauntings!).

She continues "[The solution to the hauntings] had to be kept simple. But the idea was to deliver the bones of victims to a monk, who would bless and bury them, thus setting the ghosts to rest."

In addition to this, she also states that a Kappa was also set to make an appearance, another reference to the comic (wherein Usagi Yojimbo fights a Kappa in issue #5 of the standalone comic, published in 1987).

While the team has some regrets that they weren't able to fit all this in, it appears they are still nevertheless proud of what they were able to pull off with the adaptation. And they have every right to be, judging by some of the accolades it went on to receive from the press at the time. Not only did it receive a 91% out of 100 from the magazine Zzap!64 but it also ended up getting a 90% from Crash Magazine's Nick Roberts in his second opinion review, where he dubbed it "simply enchanting" and encouraged players to run out and buy it.

The same year as the Commodore 64 release, a couple of conversions were made for the Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum, with these versions being outsourced to a company called "Source Software". Development of the ZX Spectrum version was handled by Dave Semmens and Ross Harris, while the Amstrad CPC version, on the other hand, is occasionally credited online to a team comprised of "Gregg Barnett, Cameron Duffy, and Dam". We contacted Barnett to see if he had memories of the port, but sadly he couldn't remember having anything to do with the game.

For Palmer, Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo ended up being "his swansong" before vanishing into academia, he tells us. As for Kidd, it helped to nurture their growing interest in Japanese arts and culture — something that continues even to this day.

"I went on in later life to end up as a real expert in Japanese history and mythology," Kidd tells us. "I have [knowledge of] Japanese weapon arts, and historical miniatures rules out such as Bushidan and Heiho, the Art of War. I also have a series of novels titled Spirit Hunters that are fun samurai paranormal adventures. But the Usagi Yoijimbo game remains a fun memory of the start of that journey. I also remain in touch with Stan Sakai to this day."