In 2024, FX released Shōgun, a new 10-episode miniseries starring Hiroyuki Sanada and Cosmo Jarvis, based on the 1975 historical novel by James Clavell.

The show, which like the book documented the adventures of the English sailor John Blackthorne in 17th century Japan, became a huge hit with critics and audiences, eventually leading to further seasons of the show being greenlit. Reviewers, in particular, praised the show for its performances, writing, and direction, with the famous video game designer Hideo Kojima also heaping praise upon the series, comparing it favourably to "Game of Thrones" in his own assessment on social media.

Something we should note, though — at least for those unfamiliar with the novel's history — is that this isn't the first time Blackthorne's story has been the subject of adaptation from its original source material into another medium. Back in 1980, Paramount Television produced its own award-winning miniseries starring the late Richard Chamberlain in the role of Blackthorne, the legendary Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune as Lord Toranaga, and Yoko Shimada as the interpreter and love interest Mariko.

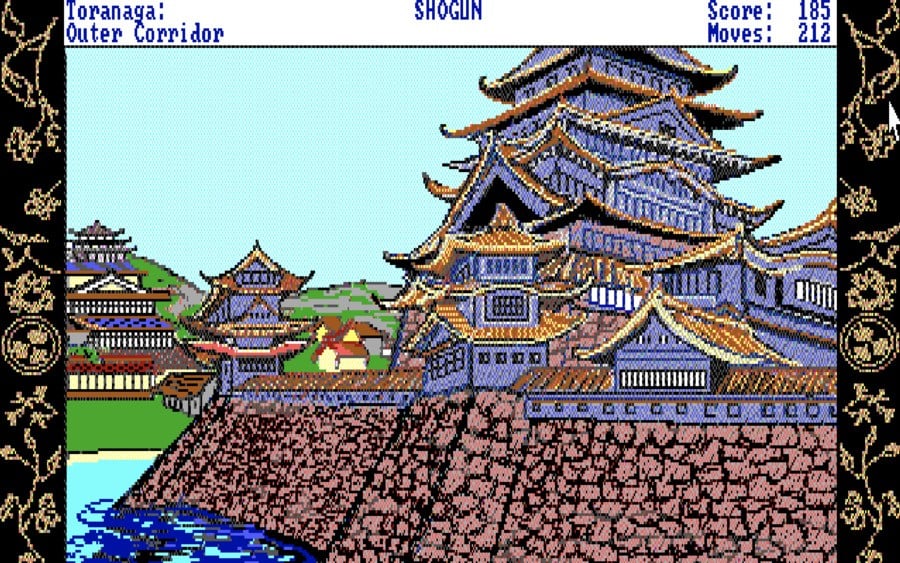

In addition to that, there have also been a few video game adaptations too, with the most interesting of these to us being Infocom's 1989 text adventure for Apple Mac, Amiga, Apple II, and MS-DOS — the subject of this article — which was written and programmed by Dave Lebling (of Zork fame) and also featured artwork from the painter Donald Langosy

Comprised of over 1000 pages filled with memorable characters, intricate subplots, and detailed descriptions of life in Japan at the end of the Sengoku period (1467 to 1600), Clavell's novel Shōgun doesn't exactly sound to us like the easiest candidate to be adapted into the text adventure format. However, in the late 80s, that's precisely what ended up happening when Lebling accepted the herculean task of whittling down those hundreds of thousands of words into something interactive, cost-effective, and (perhaps most importantly) shippable.

At the time, Infocom admittedly wasn't exactly in the best of shape. Commercial text adventures had started to fall out of favour, and the company had, just a few years earlier in 1986, been sold to Activision, after the high-profile failure of the relational database Cornerstone had left the company on the verge of bankruptcy.

This new arrangement had reportedly started out on a slightly positive note, with the publisher's president Jim Levy being a huge fan of Infocom's games. Shortly after, though, Levy was ousted from the company in 1987, instead being replaced with Bruce Davis — an individual who had opposed the Infocom buyout, to begin with, and felt the publisher had overpaid for the struggling developer (even going so far as to file a lawsuit against its founders).

Under Davis, Activision (who temporarily changed their name to Mediagenic around this time) began pushing Infocom to pursue more licensed projects and more games with graphics and also pressured Infocom to produce titles on a tighter schedule. It was against this backdrop — not exactly conducive to creativity — that Lebling began work on his adaptation of the fairly intimidating novel. Although, as he tells us, he was already pretty familiar with the book, having read and enjoyed it years earlier.

"I originally read 'Shōgun' in a big, fat paperback, while roasting on the beach in Maryland," Lebling tells Time Extension. "I really liked it. I did much more reading than swimming/surfing/etc. This was before Mediagenic was interested and well before the idea of an Infocom game from it."

As he has said before in interviews, Activision had originally sold him on the idea of adapting Shōgun by pitching it as a collaboration between Clavell and himself — similar to how the Infocom designer Steve Meretzky had worked with The Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy creator Douglas Adams years earlier. However, it soon became clear that, although Clavell was fairly interested in computers, he was simply too busy to be involved on a full-time basis as he was working on "his next movie". Because of this, Clavell's involvement ended up being reduced to just a couple of visits throughout the game's development, in which he kicked around a few ideas for potential features.

"He and his wife were very friendly during our visit to them in Switzerland," Clavell tells us. "On our second visit (to a London film studio) he was less helpful and friendly and I could see it was not worth pushing him. My memory is he never saw anything but a printout (from a line printer). We didn't have a TRS-80 or whatever it was to drag around. He read some of it during my UK visit. His one and only contribution to the game was to have 'Men's' and 'Ladies' privies. Clavell thought you could use them if the player wanted to end up as Mariko or Blackthorne — I've seen worse ideas."

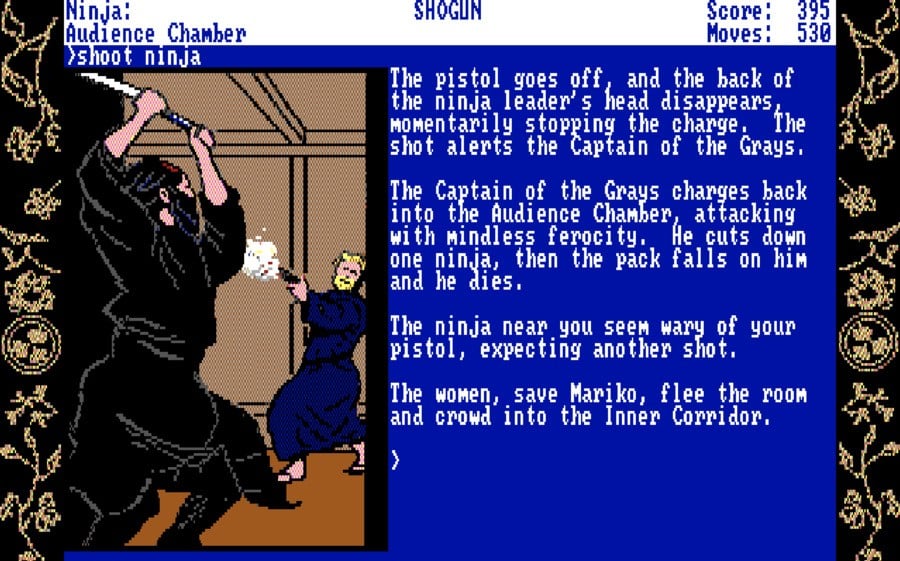

With Clavell clearly having his hands full with other projects and Lebling having a strict deadline to adhere to, the designer ended up pushing ahead on the game without him, deciding in the meantime that the book was "just too huge" and too detailed to successfully adapt into an adventure game. As a result of this, he decided to take a different path, devising what is essentially a compilation of interactive "scenes" taken from across the book, starting with Blackthorne's arrival in Japan aboard the Erasmus and covering other notable events such as Toranaga's escape from Osaka, the earthquake in Anjiro, and Yabu Kasigi's betrayal.

As is the case with other Infocom titles, to play these scenes, the user would have to type your commands into a text parser to help Blackthorne navigate this strange and unfamiliar landscape, with some scenes requiring actions to be performed in a set number of turns. A key example of this is the opening scene, which involves Blackthorne having to keep the ship on course while rousing his crew who are suffering from starvation and scurvy. In this case, if you wait too long to get the ship up and ready for the challenges ahead, the vessel will eventually approach a dangerous reef, leaving you at the mercy of the sea.

In addition to this, there is also another unique section (not repeated elsewhere), which temporarily drops the parser commands, featuring a randomly generated maze. This has players being pursued by archers through the streets of Osaka.

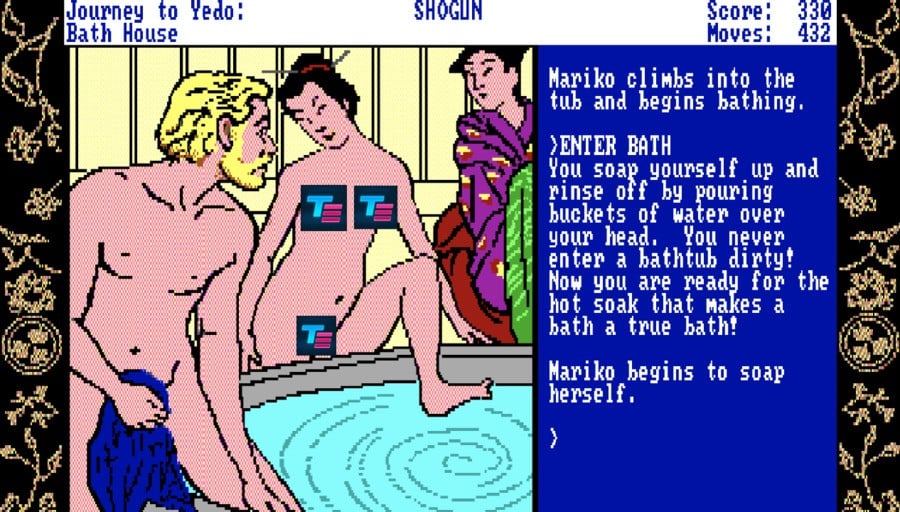

"The Erasmus segment was my favorite," Lebling tells us, reflecting on his favourite moments from the game. Meanwhile, he reveals some of the scenes he looks back on more negatively were some of the risqué moments between Blackthorne and Mariko, which he says were a sign of its difficult development. "It was sort of a joke because I famously had suggested we could get more buyers with a sex scene," he continues. "This was a tongue-in-cheek method I used for any game that was going nowhere. Sigh!"

When Lebling talks about Shōgun today, he still occasionally expresses a fondness for some of these timed puzzles, as well as for the art of Donald Langosy, who joined the project at the suggestion of his wife Elizabeth (a regular Infocom employee who worked on Infocomics games like the ZorkQuest series). But he also views the project as one of the "biggest disappointments" of his career and one that he, unfortunately, had to toil away on while the company he loved was falling apart around him.

In our opinion, Infocom's Shogun is well worth revisiting if you happen to be a fan of the book or the TV shows, even if it does happen to be a bit too linear in places making it somewhat difficult to know what to do at times without multiple attempts.