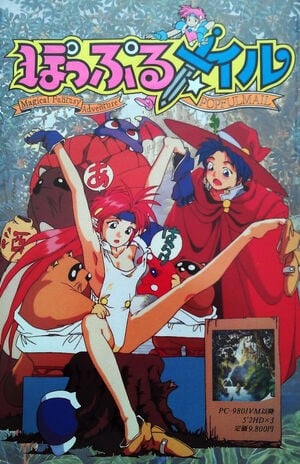

Nihon Falcom should need no introduction to Time Extension readers. Whether it's original works like Legacy of the Wizard or the Legend of Heroes series, or remakes such as Faxanadu on NES and Popful Mail on Mega CD and Super Famicom, you've probably seen or played a Falcom game.

Formed in 1981 by Masayuki Kato, the company started as a computer store, selling hardware alongside software made by others. But it quickly moved into developing its own games, helping to establish and refine the JRPG genre; alongside Enix, Square, and Atlus, it's fair to describe Falcom as one of the four cornerstones of Japan's RPG output.

Falcom is also notable as one of the longer-standing Japanese developers. Legendary companies like Hudson and Taito have been absorbed into others and faded from public relevance, whereas Falcom is still creating smash hits, including newer entries in its Ys series, most recently Ys IX: Monstrum Nox.

That's quite impressive, isn't it readers? But what if we told you that around 1989, there was a slow but steady exodus of staff, the company's output dropped, and Falcom almost ceased to exist? Searching online for the history of Falcom mostly brings up sterile interviews with current president Toshihiro Kondo, who took over in 2007. He goes to great lengths to hide any of the company's struggles. There are only a couple of places which describe Falcom's near collapse, and these lack first-hand sources. The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, however, interviewed multiple developers who worked for or with Falcom. All of them gave broad reasons for the staff walkout.

Then-president Masayuki Kato didn't pay staff enough, was narrow-minded over new hardware, and generally mistreated those who worked for him. As you'll discover, Falcom was not above hiring underage middle-school kids to help with programming, removing the credits of staff, denying holidays on national days of mourning, and refusing to share bonuses from blockbuster hits. These are serious allegations though, so we present to you the words of those involved with Falcom as they were spoken.

Mikito Ichikawa, president of Mindware (MaBoShi: The Three Shape Arcade)

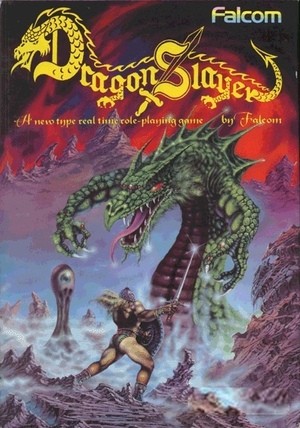

"Starting from around the autumn in 8th grade, when I was still in middle school, I started working part-time at Nihon Falcom. I worked there starting in the autumn when I was in 8th grade, so around 14 years old I think? I just went there directly, about 20-30 minutes by bicycle. I worked on Xanadu, and also a PC-6001mkII version of Dragon Slayer, but it was never released."

Toru Hidaka, programmer for Enix, programming lecturer

"The majority of people making games in those days lost their jobs or went out of business. I myself ended up writing programming books. No matter what job you do, it's not guaranteed to last forever. When you look back, you see it as just a brief, shining moment. The same is true of the game industry. If a company cannot survive without assistance, sooner or later it's bound to fail, just like in any other industry. The software houses we've discussed, like Bothtec, and T&E Soft, and Falcom, they all faded away. Falcom may be doing well, but they're a different company now. Kiya-san [Yoshio Kiya, Dragon Slayer creator] is no longer with them. They're still using things like monetising schemes in social games to raise profits. It's a totally different way of making money."

Kouji Yokota, artist and designer on Valis, Megami Tensei, Exile, Gaiares, ActRaiser, Soul Blazer, Illusion of Gaia, Robotrek, Lunar: Eternal Blue, and Granstream Saga

"The Showa emperor had passed away [7 January 1989]. This big funeral was held, and there was a huge discussion within the company whether there was going to be a day off for this special occasion. It turned out that we did not have a holiday! I was with Falcom until around 1991. Actually, I wanted to leave with Masaya Hashimoto and Tomoyoshi Miyazaki, when they left to form Quintet in April 1989. But I had a family, so I didn't leave with them. When those two left, obviously the company didn't like that and there were problems, with regards to them leaving. So I didn't want to go with them, because I wanted to avoid having any trouble with the company. And then Yuzo Koshiro of Ancient left.

Falcom was a conservative company, and consoles were gaining momentum rather than computers. We had this desire to do console games, but the company said no. Nintendo's cartridge ROM business was considered high risk. So the company was reluctant to follow that. Having said that, maybe they were right in not doing it, because Falcom still exists. Maybe as a management decision, they made the right one. But as a creator, I was frustrated by the company's attitude. For example, we wanted to make an action game for consoles that was similar to Ys III, but we couldn't do that. But later on, we realised these desires with ActRaiser."

Yuzo Koshiro, composer on Ys, Streets of Rage, and many others

"It's always the case that Falcom don't credit me. I know they don't credit me, but I don't know why. I don't know if it's because of some company reason. In terms of vinyl records or cassette tapes, or games, that were released when I was in Falcom, they did credit me. But after I left, any CDs or anything published, including games, whenever my music was used in those things, they never credited me. It was actually my mother's idea to have my name credited and displayed on the screen! <laughs> As I described, there were some difficulties with Falcom, and I think my mother had that in mind as well. I think my mother always had the idea that the composer should have rights. I think she felt the same way for games, that composers should declare their rights for the music that they compose."

Jun Nagashima, Popful Mail

"After development of Ys III ended almost all of the associated staff quit Falcom. I was alone and the section manager said, 'You're capable of programming, come up with something.' But I was the only programmer left, and I had no graphic data, so I was really at a loss. I was told to make a game but had no planner and no designer. I focused on creating a prototype by reusing existing Falcom assets, which became the basis for Popful Mail.

After finishing development on Dinosaur, Kazunari Tomi also quit the company, without even waiting until the game's release. At Falcom, it was forbidden for programmers to insert staff credits into their games. However, Tomi-san broke this rule and inserted staff credits into Dinosaur. But since Tomi-san quit before the game's release, another programmer went in and deleted the credits.

Yoshio Kiya was Falcom's head of development, and he was effective in his role as a leader. Years later Kiya-san also left Falcom. I wondered what happened when he suddenly stopped coming in to work one day. When I heard that he had quit, I remember feeling uneasy about Falcom's future.

Many people quit Falcom around this time, and the people who left the company would often get together and go out for drinks or something. One time I was out with Tomi-san, and we had a conversation about how I was thinking of leaving Falcom. A few days later he phoned me at home, and introduced me to a game company he was acquainted with."

These standalone statements from various developers portray a company where their efforts went unappreciated. However, as one would expect when interviewing the Japanese, the answers were always polite, reserved, and reluctant to attribute blame or speak too openly. To truly get a feeling for the zeitgeist, one needs to speak with Yoshio Kiya, the legendary Falcom programmer behind the Dragon Slayer series. His creations would become Japan's biggest-selling hits of the time. He was also unafraid to answer questions bluntly.

In a three-and-a-half-hour interview for The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, he was grilled on every aspect of Falcom. Specifically, he was asked about Xanadu which, in 1985, is reported to have sold record numbers. Did this skyrocketing success change the atmosphere at Falcom? "Kato-san's house got bigger!" replies Kiya, with a sardonic tone so dry you could almost feel the tatami mats change shape. As he would go on to describe, the dissent among staff was not an overnight phenomenon. A feeling of malcontent had slowly grown over the years.