Cast your mind back to the video game landscape of the early '90s, and 2D remains king. Granted, 3D gaming was on the rise thanks to titles such as Star Fox, Alone in the Dark, Virtua Racing and Doom, but with the wave of 32-bit consoles yet to materialise, the industry was at an odd crossroads; CD-ROM tech had mostly been used for FMV and pre-rendered titles like The 7th Guest, Night Trap and Myst—games which promised an immersive, cinematic experience yet lacked a deep and meaningful degree of interaction.

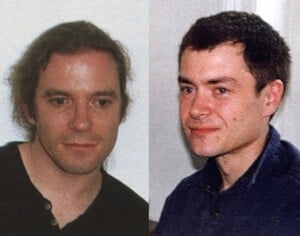

Into this landscape, a tiny two-man UK studio released a game which offered an innovative way to represent characters in 3D whilst maintaining a film-like level of storytelling and player agency, making it far more suitable for the name "interactive movie" than any of the FMV pretenders of the 1990s; it also joins Alone in the Dark as a pre-Resident Evil example of a what would eventually be known as "survival horror". That game was 1994's Ecstatica, developed by Andrew Spencer (of Andrew Spencer Studios) and Alain Maindron.

Spencer is one of the game industry's true enigmas. He cut his teeth on the C64 with International Soccer, International Basketball and Street Sports Basketball before shifting his focus to Ecstatica—a project which would take five years to bring to life. During this time, Spencer created a game engine based around ellipsoid graphics rather than polygons; this not only lent Ecstatica a unique look but also made the characters appear lifelike at a time when even the best 3D games available sported an angular, unrealistic look.

Ecstatica wasn't unique in this approach; around the same time in 1994, Accolade published PF.Magic's Ballz on the Sega Mega Drive / Genesis and SNES, a fighting game that features characters constructed entirely from spheres. However, for those who still remember the game today, Ecstatica's look remains its most significant talking point. Speaking to EDGE magazine shortly before release at the close of 1994, Spencer explained that ellipsoids made more sense than polygons as Disney's animators "used circles because they are the easiest shape to keep constant between one cel to another."

It's fitting that Spencer cites hand-drawn animation as an inspiration, as Frenchman Maindron worked in that world before joining the Ecstatica team, plying his trade at Amblin Entertainment and Walt Disney Studios. He found himself in London at the time Spencer made contact through a mutual friend, working as the boss of a 2D cartoon company, and Spencer's engine made the transition from animation to video games almost effortless. "Andrew had created a 3D editor where I could work the 3D without much code knowledge," Maindron tells Time Extension. "I could create backgrounds and characters and animate them pretty easily. Then he improved the engine, and I could even code the behaviour of characters."

Maindron's background meant he could quickly bestow Ecstatica's cast of characters with a surprising amount of expression and emotion. "I could animate the characters without thinking about it and try to figure it out because, at the time, it was the Wild West, with no rules, no school, and no YouTube." One element Maindron was especially pleased with was the fact that using ellipsoids allowed for smooth 'in-betweening' when characters shifted from one action to another; with traditional 2D characters, this process was far more time-intensive.

Despite the cartoonishly rounded nature of the game's cast, Ecstatica was violent enough to warrant the ELSPA giving it an '18' age rating in the UK. It has its fair share of distressing scenes (as well as nudity—ellipsoids, as you can imagine, are especially good when it comes to displaying male genitalia), including impaled NPCs and a fair amount of blood. Viewed through a modern lens, it all looks amusing, inoffensive and unrealistic, but it nonetheless left quite an impression on PC gamers back in '94. Ecstatica is also notable for allowing the player to choose between either a male or female protagonist, with the latter choice leading to one of video gaming's first lesbian kisses.

Another notable aspect of Ecstatica is the fact that it has no on-screen UI. The player character's health is denoted by their posture; they limp and hold their arm when they've taken too much damage. Likewise, there's no inventory to wrestle with; your character can only carry two items at once. Speaking to EDGE in 1994, Spencer explained that the goal had always been to "get people totally involved" with the action, and that meant removing anything that would break the immersion. "Menubars, boxes and statistics are the scourge of atmosphere in games, so we've designed the system to work without them. We want people to forget they're playing a game." Indeed, Spencer adds in the same interview that he feels "the writing's on the wall for films as the pre-eminent form of entertainment. They will be replaced by games in the foreseeable future."

Ecstatica's medieval setting is brilliantly realised via a series of static locations, many of which are rendered using a combination of polygons and ellipsoids, with the latter proving to be successful when representing stonework or caves. However, the fixed camera perspective—a genre staple established in Alone in the Dark and one which would continue throughout the decade via other survival horror titles like Resident Evil, Deep Fear and Dino Crisis—did cause some headaches.

"We had limitations; it is hard to be fully immersive and dynamic with a fixed camera," laments Maindron today. This drawback led to one of the most common complaints directed at the game when it launched—it was difficult to make blows connect due to the constantly changing viewpoint. Maindron also feels that the 'tank' controls—which were bound to the PC's keyboard—held things back. "We did not fully understand that ease of movement is fundamental to a pleasant experience; we should have copied Mario for that."

Nonetheless, when it launched on PC in December 1994, Ecstatica gained rave reviews from the press. Computer & Video Games ranked it "a must buy" and a contender for PC game of the year in a glowing 90% review. EDGE, meanwhile, awarded it 8/10, saying that "it's not just a good game; it engages you on an emotional level, invoking fear, wonder, revulsion and delight in equal measure."

The positive reception afforded to Ecstatica would have made it easy for Spencer to tempt publisher Psygnosis with a sequel, but when speaking to EDGE in 1994, he made it clear this was the plan even before release. "I haven't spent the last five years creating just one game. I now have this system, and there will be sequels." However, the immediate plan wasn't to produce a direct successor but to instead use Spencer's powerful ellipsoid engine to create what feels like it could have been a precursor to the Grand Theft Auto.

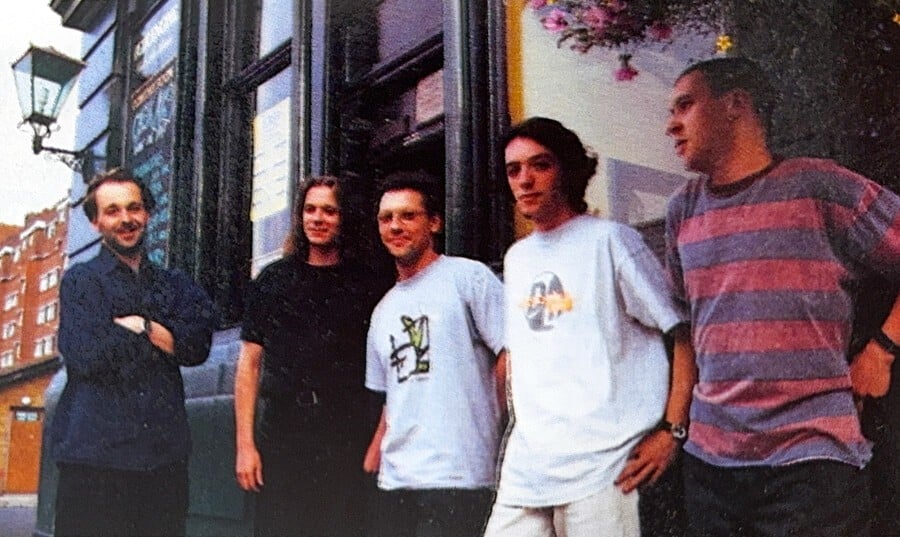

Urban Decay sought to retain Ecstatica's gore and violence but placed the action in the modern era, swapping swords for guns and werewolves for human enemies—including the police. "Ecstatica was the testing ground for the system—we always had plans to take it further," Spencer told EDGE magazine in August of 1995. The game's hero is framed for a crime he didn't commit, leading to an intense city-wide battle to prove his innocence. In the months that followed Ecstatica's launch, Spencer expanded his team to include five animators and a background artist, and Urban Decay's early previews quickly stirred up considerable interest in the press.

Those who found Ecstatica's propensity for shocking scenes appealing would be well served by Urban Decay, it was claimed. "The appeal of Reservoir Dogs is interesting and in some ways comparable," Spencer tells EDGE when discussing the game's level of violence. "In Urban Decay, you're pressing the button to blow someone's head off. And everyone seems to like that, not just sick people. People have pent-up aggression." Spencer adds that the game offers consequences for such actions, however. "If the player acts like a complete psycho, he'll be treated like one."

One person who wasn't involved with Urban Decay was Maindron. "After Ecstatica, we were planning Ecstatica II and Urban Decay, but we disagreed on the direction to give it," he explains to Time Extension. "Andrew wanted to create a company as the only boss, where we had always been on an equal basis until then, [there] being only two [of us]. So, the split happened." Despite this example of good, old-fashioned creative differences, Maindron only has good things to say about the experience of working with Spencer on Ecstatica. "[He's a] nice person, [and] courteous. [He] takes a long time to answer a question because of his coder frame of mind; because he only answers when sure. He is very talented and, in fact, one of the best. During Ecstatica, we had a very nice working relationship."

Ultimately, progress on Urban Decay was hampered by the fact that key team members left to join Disney (an ironic reverse of the situation which saw Spencer and Maindron combine on the first Ecstatica), and this forced the team to pause production and create Ecstatica's true sequel, which launched in 1997—the same year that an upgraded version of the original launched for Windows. Developed by a core group which included Spencer, Neal Petty, Marcus Wagenfuhr, Ken Doyle, and Dave Lowry, Ecstatica II retained Spencer's ellipsoid engine but boasted higher-resolution visuals thanks to SVGA support.

"The main advantage is the organic-looking characters," Spencer told EDGE in 1996 when asked why he and his team continued to use ellipsoids instead of triangle-based polygons (like pretty every other game at that point in time). Certainly, this was a more pertinent question in 1996 than it was when the original game was in development a couple of years previously. "Triangles tend to make hard, robotic-looking figures, whereas ellipsoids can be used to create rounded, more human alternatives," reiterates Spencer, echoing the comments he made back in 1994. "Ellipsoids can also be more efficient because you can make a much better-looking character out of fewer shapes."

While Ecstatica II was a notable improvement over its direct forerunner, offering a larger environment, more characters and a wider range of movements for the protagonist, its reliance on ellipsoid-based visuals ironically limited its commercial chances. Speaking to EDGE in 1996, Spencer admitted that any potential PlayStation port would be "particularly difficult" as Sony's 32-bit console was "geared towards triangles, not ellipsoids. Furthermore, ellipsoids are mostly software-driven, which the PlayStation doesn't really like. Ellipsoids and the PlayStation don't really go together."

Had Ecstatica II been ported to Sony's console, it could have changed its developer's fortunes. By 1996, PlayStation was booming globally, while Andrew Spencer Studios was counting the cost of Urban Decay's stop-start development. Speaking to the now-defunct PC Games That Weren't, Psygnosis composer Mike Clarke gave some insight into why the game never saw the light of day:

There were loads of tech demos done, and the game looked amazing. It was still a bit 'Alone in the Dark' in parts with fixed camera locations, but was very good. It was pretty much the first proper adult game I’d seen, with swearing and 'proper' violence in it. The stuff I saw was character [animations] synced to voiceovers, some rag-doll demos, and a warehouse scene where you could stealthily walk up to someone from behind and slit their throat, or lean out from behind crates shooting with a gun in each hand. The only thing that I remember hearing was that they couldn’t make a good enough game out of it. They had all of these bits and pieces of 'cool stuff' but took too long to get anything together into a coherent whole. It was a great shame because it was the game that I was looking forward to the most out of all of the games of that era.

Speaking to Unseen 64, Andrew Spencer Studios artist and in-game programmer Ken Doyle shared a little more detail:

Basically various issues assailed and eventually sunk the project. Firstly, the main creative and design force behind the game, a guy called Eamon Butler, left to pursue a successful career at Disney. He became frustrated with endless requests for design and style changes. It was originally due to be an ellipsoid game but later changed over to a more regular poly look for the sake of realism. Urban Decay was shelved so work on Ecstatica 2 could begin. We returned to Urban Decay, but the studio's relationship with Psygnosis soured, and that was that. [The] studio closed, and we all moved on.

Spencer's career in games appears to have stalled at this point. He moved into science and academia, working at Sheffield University's Dynamics Research Group. Outside of chatting with Retro Gamer magazine about the making of his C64 games, he doesn't appear to have spoken in-depth about his groundbreaking contribution to the world of survival horror. In the same interview—which took place back in 2008—he admits to returning to the "game industry wilderness" following the closure of Andrew Spencer Studios but hints that he is working on ideas for his next game. At the time of writing, 17 years later, that game still hasn't materialised.

That's a real shame because an interview with EDGE (again) at the close of 1996 suggests he had plenty more ideas about where to take the action-adventure genre, and video games as a whole. "The next step is to create games which combine exciting gameplay and realistic graphics to produce a truly adult experience—and I don't mean pornographic. To take this step will require that not only entertain, but touch on real-life issues and experiences. When men and women go down the pub and talk about what happened to them in a game without boring the pants off everyone else, then the medium will have begun to mature."