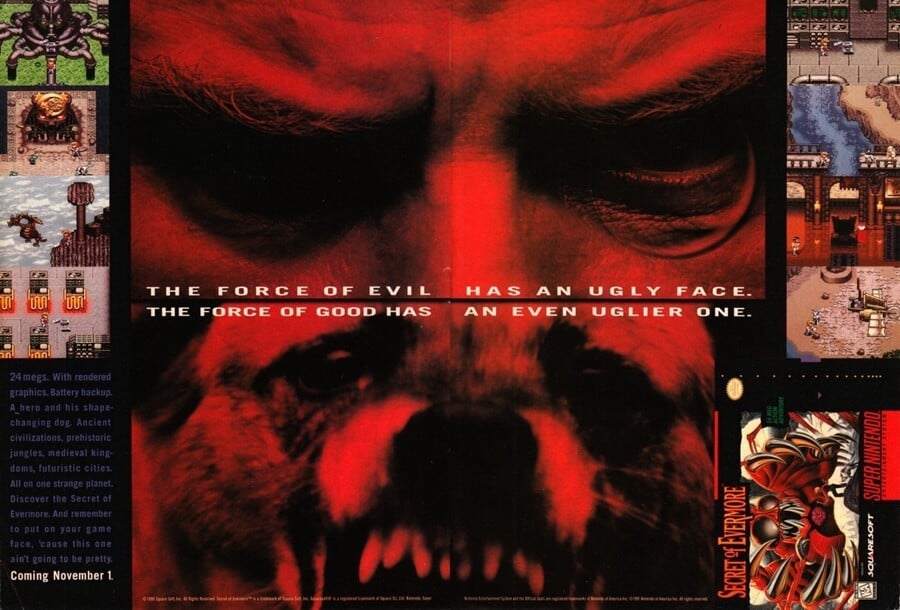

Square's Secret of Mana is a truly legendary video game. The second in the Seiken Densetsu series (but the first to use the 'Mana' branding in the west), it garnered rave reviews and achieved sold sales, establishing a lineage that continues to attract fans even to this day. However, while Mana has gone on to achieve lasting fame, another Square title from the same period has been largely forgotten outside of a core group of hardcore fans. That game is Secret of Evermore, a 1995 SNES title which was created in the wake of Mana and is unique in being the only Square game made by designers in North America.

We originally worked on a game called Vex and the Mezmers... however, after a pre-mortem of sorts, we decided it just wasn't up to snuff

"I got involved in game development largely as a fluke," says Brian Fehdrau, who served as the lead programmer on Secret of Evermore. "I loved gaming as a kid and wrote some simple games on my own in high school and college, also contributing some pretty rudimentary artwork to a friend's games. I didn't get into it professionally until I was desperately looking for a job so I could start paying off my looming student loans. Honestly, I would have taken just about anything. One of the offers in the newspaper mentioned looking for applicants who had 6502 assembly-language programming in their repertoire. I'd done some 6502 tinkering on my trusty C64, so I applied. As it turns out, that was the Squaresoft job, looking for people to write a game for the SNES, which used the 6502's 16-bit successor, the 65816. I guess they liked me because they called me back after the interview and offered me the job."

Fehdrau explains that Secret of Evermore evolved from a prior title his team had been working on. "We originally worked on a game called Vexx and the Mezmers, named after its antagonist, with some of the same themes," he says. "However, after a pre-mortem of sorts, we decided it just wasn't up to snuff, and we basically started a new game with a new story, new settings [and] new art. However, many of the themes seemed to me to carry over to the new context. It's hard to pin it down. It definitely evolved over time, during development."

With this being the '90s, the size of the Secret of Evermore team was always on the compact side, even if it did fluctuate during development. "The team size varied over time, from just me, Doug [E. Smith, Executive Producer], and Alan [Weiss, Concept Producer] at the start, to around 25 near the end, plus a couple of QA guys, a few Final Fantasy game counsellors who doubled as testers for us, and the IT guy," Fehdrau recalls. "Many, myself included, were brand new to the industry. I seem to recall that Doug said he'd been instructed to make such hires as much as possible, partially to keep senior people's salaries from eating up the budget and partially to bring fresh ideas to the table. However, about half of the team had prior experience. It seemed as though we hired almost everyone who had worked for Manley & Associates, which later became EA Seattle. We also picked up a number of people from Humongous."

As a gaming platform, the SNES was really quite awesome.. I'm speaking both as a gamer and a game dev

The SNES was perhaps at the height of its commercial power at this point, and the next generation of systems was looming on the horizon. However, this didn't diminish Fehdrau's desire to work on the console. "As a gaming platform, the SNES was really quite awesome," he says. "I'm speaking both as a gamer and a game dev. The trickery it allowed was pretty vast, and by that, I mean you kept on figuring out more and more things you could do if you fiddled with the right bits the right way."

Still, the fact that the platform was Japanese created some headaches. "I sometimes wished I spoke Japanese, because the hardware was clearly designed with a lot of the things we ended up doing in mind, but because the documentation was so sparsely and poorly translated, we often didn't know until we figured it out on our own," Fehdrau adds. "Still, it was a lot of fun to work with. In many ways, it made things a lot easier on the dev than you'd expect an early-'90s bit of hardware to do. A lot of the things I would have struggled to do in real-time on my Amiga were directly supported in hardware, such as Mode 7 image scaling and rotating."

The remit for Secret of Evermore was simple enough; Square wanted a 'western RPG' – and by that, we don't mean a Wild West setting, but an RPG made by westerners that would appeal to westerners. "As I understood it from Doug, the VP of development who hired me, he met one of the big names from Square Co. Ltd, the original Japanese company, and suggested to him that Square should consider making games specifically for our market," explains Fehdrau. "They liked the idea and hired him to make it happen. This direction was repeated to us at several points during development, so it was clearly our prime directive, so to speak."

I personally thought Mana's action-oriented gameplay was superior to the turn-based gameplay of Final Fantasy, and still do

It helped that Fehdrau was a massive fan of Secret of Mana, as that title would provide a template of sorts for the new game. "Secret of Mana was a huge inspiration," he says. "I personally thought Mana's action-oriented gameplay was superior to the turn-based gameplay of Final Fantasy, and still do. Not only that, but the direction to make a western RPG included the detail, 'similar to Secret of Mana.' Perhaps it was assumed this would also appeal to western tastes more."

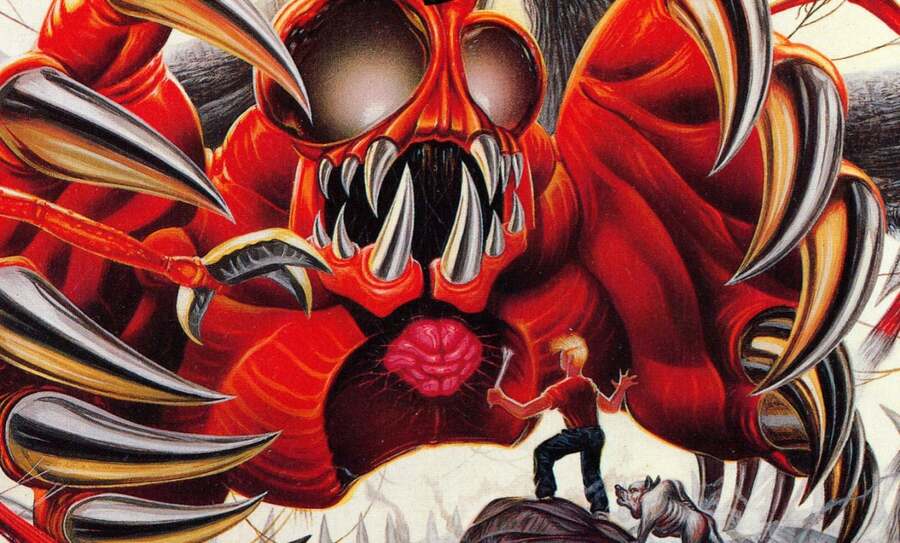

While the team at Square's North American office clearly had a good foundation to work off, Fehdrau admits that he wasn't entirely keen on slavishly imitating every aspect of Mana – but the fact that the game was so polished meant that finding alternative ways to handle things in Secret of Evermore was tricky. "We didn't intend to make something quite so similar to Mana," he tells us. "The truth, though, is that we often couldn't come up with better mechanics for the prescribed genre. I consider this a credit to Mana's engineering team and their years of experience. Thus, after a while, we simply decided to create a game that felt like it was using the same engine but with tweaks and a new story. To our credit, most people thought that's what we did, even though we actually wrote everything from scratch. It probably didn't help that the marketing guys added 'Secret of' to the name, which was simply 'Evermore' until the last couple of months of development. As an aside, I do love our alchemy system, which was unique to Secret of Evermore."

Given that the American team was attempting to recreate the magic of Secret of Mana, it's tempting to ask if there was ever a sense of competition or even animosity between Square's east and west offices. "I was never aware of any sense of competition, at least not a prominent or hostile one, between the Japanese teams and us," replies Fehdrau, nixing that particular hunch. "That would run counter to what I now know of the Japanese work environment and their 'we're all on the same team' kind of work ethic, so this isn't surprising in retrospect. We did have visitors from time to time, and they would survey what we'd done recently, but they'd mostly just nod politely and not give a lot of direct feedback. I was told this was not unusual when dealing with Japanese devs, as people wanted neither to speak poorly of a potential success, nor to ally themselves with a potential failure. I don't know how accurate that generalization was, but it certainly matched the observed behaviour. That being said, indirect feedback was common. For instance, on one visit, we showed off a Mac-based tile and map editor I'd been working on, and on a subsequent visit, they demoed a startlingly-similar Mac-based editor they'd created for Final Fantasy VI (AKA Final Fantasy III). I took heart from what seemed to be approval of my design."

Fans were less diplomatic... They really wanted more JRPGs. Heck, I wanted that too. Evermore wasn't that. Even if the end result was fun, it would make people angry that they were looking forward to one thing and got something rather different

That editor was called S.A.G.E. (Square's Amazing Graphical Editor) and was a powerful tool in the development of Secret of Evermore. "It was intended as an all-in-one editor, where one could create sprites, animations, tiles, and maps and then export them en masse for the game," explains Fehdrau. "Only programming, audio, and scripting were done outside of S.A.G.E., though many things were cross-linked so that one could still access the other, such as scripts having access to named map locations or to character animations. Later on, we obtained some 'test station' pseudo-cartridges, which were basically a cart with RAM emulating ROM and a parallel port you could use to change the RAM on the fly. We'd upload a special version of the game to the cart – which, by default, had only one very limited map and just the main character – but S.A.G.E. was able to upload a new map and new characters and animations. This allowed artists to do live previews of animations and maps on real hardware, with all of its caveats and weird analog-colour-TV artefacts."

When Secret of Evermore finally arrived in stores on October 1st, 1995, reviews were positive, but the overall critical reaction was perhaps more muted than Square might have been expecting – especially after the universally positive critical reaction to Secret of Mana. "I felt Evermore's critics were lukewarm: neither particularly kind nor cruel," reflects Fehdrau today. "Fans were less diplomatic, however. They really wanted more JRPGs. Heck, I wanted that too. Evermore wasn't that. Evermore was more like taking Neon Genesis Evangelion and having 4Kids retool it for American middle-schoolers. Even if the end result was fun, it would make people angry that they were looking forward to one thing and got something rather different. People didn't want a lighthearted, G-rated, B-movie-styled romp through fantasy Americana. They wanted more darkness, unfamiliar Eastern lore, and more of Kefka going 'GWHAHAHAHA' before doing something evil. So I get it, but it was hard on my ego at the time."

To make matters worse, a rumour started around this time that Secret of Evermore's release precluded the localisation of Seiken Densetsu 3 (AKA Secret of Mana 2, or Trails of Mana, as it would eventually be called when it eventually arrived in 2019 as part of Collection of Mana. You can sense that Fehdrau has been asked about this before on more than one occasion, and he's quick to shoot the misconception down.

"No, there's no truth to our project pre-empting the localization of Secret of Mana 2," he says. "Our team was entirely separate from the people who did localizations and had no effect on them. They existed before our team was formed, translating Final Fantasy II not long before I started, Secret of Mana during my first couple of months on the job, and Breath of Fire in there somewhere as well. If anything, the expansion of the staff and facility freed up a lot of people from having to be jack-of-all-trades on what was previously a skeleton crew of about five people doing Squaresoft's NA publishing. Truth be told, several games actually were localized during Evermore's development, including Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy VI/III. They actually borrowed our team to test the Final Fantasy VI localization rather than hiring outside people, so if anything, we helped to bring that one to market. There were other reasons why Secret of Mana 2 was not localized, but what I know of them is a combination of uncertain and inappropriate-to-disclose, as I was never officially in that loop."

The gradual warming of the audience to our game has really cheered me up over recent years. It was the mid-2000s when I finally stopped apologizing automatically when someone told me they'd played Evermore. These days, I'm proud

Secret of Evermore's failure to instantly replicate the commercial and critical performance of Secret of Mana had a predictable impact on the fortunes of both the game as an ongoing concern and the team that made it. "After the game went gold, there was brief talk of a sequel, but that got nixed," Fehdrau reveals. "Instead, we split into two teams and started work on a couple of new projects. I was on one called Alien Reign, which was a Warcraft-style strategy game. I was having a lot of fun with it, actually. Unfortunately, Square's US office closed about six months later, I think. Square LA had been set up, and I believe they were hiring for Parasite Eve, if I remember right. I gather the reception Evermore got – coupled with the desire of Square Japan's people to visit/work in LA, where the weather isn't rainy all year, and Hollywood is right there – determined our fate pretty easily. All but a few of us were laid off. Those few dismantled the office and then departed as well. I think only our legal counsel actually moved to LA, even though I seem to recall that Square billed it as a 'merging of offices'. The rest of us ended up at other game companies in the area, which was booming with both existing studios and startups."

As has been the case with fellow 1995 SNES flop EarthBound (which, ironically, also has an Americana setting), time has been kind to Secret of Evermore. Over the years, it has gained a loyal group of fans who continue to lobby for its reappraisal. It's gratifying to note that Fehdrau has noticed the shift, too. "The gradual warming of the audience to our game has really cheered me up over recent years. It was the mid-2000s when I finally stopped apologizing automatically when someone told me they'd played Evermore. These days, I'm proud. In fact, I think it's the game I'm the most proud of. Honestly, it may be minor in comparison, but it's given me a lot of compassion for artists and writers who died in obscurity before people discovered their work. Poor Edgar Allan Poe, destitute and delirious at the end, never knowing the respect his work would later receive. I've not done anything as lasting or important as, say, The Raven, but I still feel privileged to have had the opportunity to see something I thought was scorned actually receive some love."

Fehdrau has now retired from games development, but he's still happy to hear positive stories about Evermore from the fans who enjoyed it back in the day. "I really appreciate every single fan who's told me their story of playing it as a kid on summer vacation or sneaking down to play it in the family room after midnight," he concludes. "When someone tells me it's their favourite game, I'm still floored. I think it's amazing to have this weird kind of invisible link to so many strangers' lives. I'm pretty self-critical, and for years I thought the best I'd managed with my career was to keep a few kids from doing their homework. It's pretty cool when I realize that I actually helped people have fun."