In 1990, the world of video games changed forever. Lucasfilm Games released The Secret of Monkey Island, a foundation stone for the graphic adventure genre. Its bang-on-target jokes, its rounded leading characters, its high-energy dialogue trees and that legendary sword fighting sequence remain best in class. Guided by director Ron Gilbert’s philosophy of adventure design – from his 1989 treatise “Why Adventure Games Suck And What We can Do About It” – Monkey Island was dead serious about being deeply funny.

A sequel arrived quickly, then after five years, another. Like a zombie pirate refusing to drop dead, Monkey Island came back for a fourth round and a fifth over nearly two decades. However, Monkeys 3 through 5 lacked Gilbert’s guiding light. Purists shunned the new entries, awaiting a mythical alternative third game that they believed Gilbert had planned out. That same hope, now 31 years old, fuels the excitement for this month’s Return to Monkey Island.

But, before we get to that, let's have a lool back at the full history of the series, shall we?

The Secret of Monkey Island (1990)

The hallmarks of Monkey Island’s design are captured in three of Gilbert’s principles: make puzzles that aren’t “backwards”, that “advance the story” and that “give the player options”. So, don’t reveal a solution before the problem is encountered, don’t abstract puzzles from the story, and don’t “cage the player”, providing too little to do at once.

In The Secret of Monkey Island, the player immediately meets three parallel challenges – The Three Trials supposed to bestow piratehood. You can move, uncaged, to a different trial when you’re stuck. Puzzles are extended through long, logical chains, fastidiously mapped out in “puzzle dependency charts”, and embedded in the story, dispensing rewards of new characters, items, dialogue and – that very tastiest of morsels feeding the graphic adventure compulsion loop – whole screenfuls of new graphics.

Gilbert has discussed many times – most recently with our sibling site Nintendo Life – the intentional cluelessness of protagonist Guybrush Threepwood at the start of the game. The player is not a seasoned pirate, so neither is their proxy. Throughout the game, Guybrush fakes it till he makes it, manifested in an improvisational approach to puzzle design. For example, he must follow a recipe on a ship, but none of the ingredients are available, so credence-stretching alternatives must be found.

This style permeates, from the stand-in navigator’s head to the ultimate root beer to, less obviously, the game’s most famous puzzle: insult sword-fighting. Here, dialogue options from one context are re-applied improvisationally on encountering the Sword Master – essentially bluffing through another recipe. Like the green Guybrush, you don’t know how to be a pirate until, at the end of the game, you realise, somehow, you are one.

So much more could be said: The Secret of Monkey Island laughs at itself with too-convenient items (“rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle”?), toys with the genre-typical ability to pick almost anything up (that time by the dock), creates puzzles from dialogue, delivers perfect comic timing with just text and pixelated glances at the camera… but we have more games to get to.

Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge (1991)

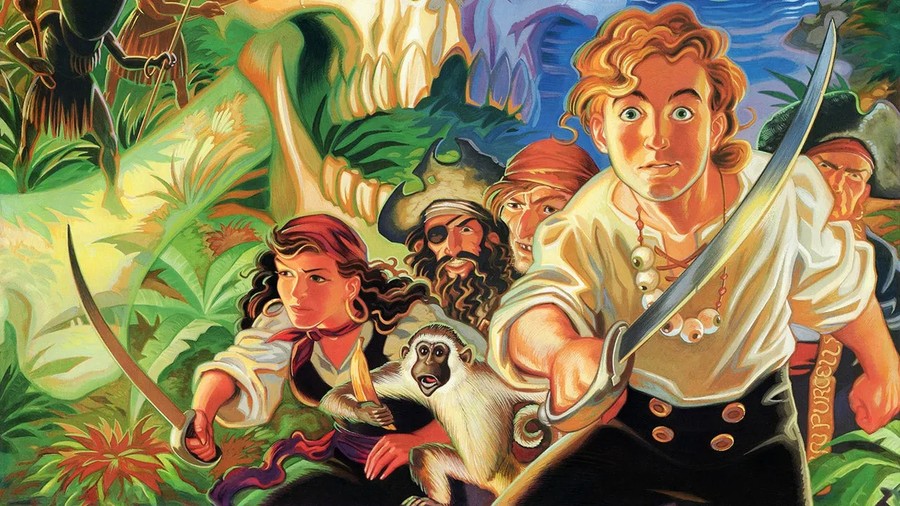

Again directed and designed by Ron Gilbert, Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge brought together the same writing team of Gilbert, Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer, plus Steve Purcell carrying on as artist. The style, the feel, the world were the same – but more.

The Secret of Monkey Island first released in 16 colours Purcell described as “ghastly”. LeChuck’s Revenge launched in 256 colours straight out of the gate, looking stunningly rich, every scene overflowing with intrigue and mystery, a delight to mouse over and explore. Painted backgrounds were scanned in, cutting-edge tech creating scenery greater than the sum of its pixels. The screen’s inventory section saw big, characterful pictures replace The Secret of Monkey Island's text list.

Composer Michael Land returned, and the eerie themes of the first game got their own technological upgrade through Lucasfilm’s new iMUSE system. MIDI music tracks adapted to player actions and story events on cue, creating a seamless, unique soundtrack that followed the player.

The enhanced technology supported a bold vision. LeChuck’s Revenge was dramatically bigger than The Secret of Monkey Island, with longer chapters, more areas, puzzles more numerous and more complex, and a vast, interconnected world all in play at once. If players felt “uncaged” in the first game, they would be nigh on agoraphobic by the second chapter of Monkey Island 2. The excitement of a creative team at full stretch comes across, but occasionally so do some signs of overreaching. With such an open world, it became impossible to shepherd players to find puzzles before the items that solved them. Inevitably, then, some puzzles ran “backwards”. And less linearity made driving the story harder – there was more chance to feel lost.

But for any problems it had, LeChuck’s Revenge paid out tenfold in fun, energy, imagination and the sheer volume and sumptuousness of hilariously written, drawn and animated rewards.

For his part, Guybrush was barely less naive than before, although a little more gung-ho (“Use saw with peg leg”!), and the improvisational puzzle style carries through, giving the sense that he’s maintaining his tentative pirate status only by lucky guesses, a fair wind and the seat of his pants. Some examples are the replacement monocle and, for better or worse, the infamous monkey wrench. Fans and critics lapped LeChuck’s Revenge right up.

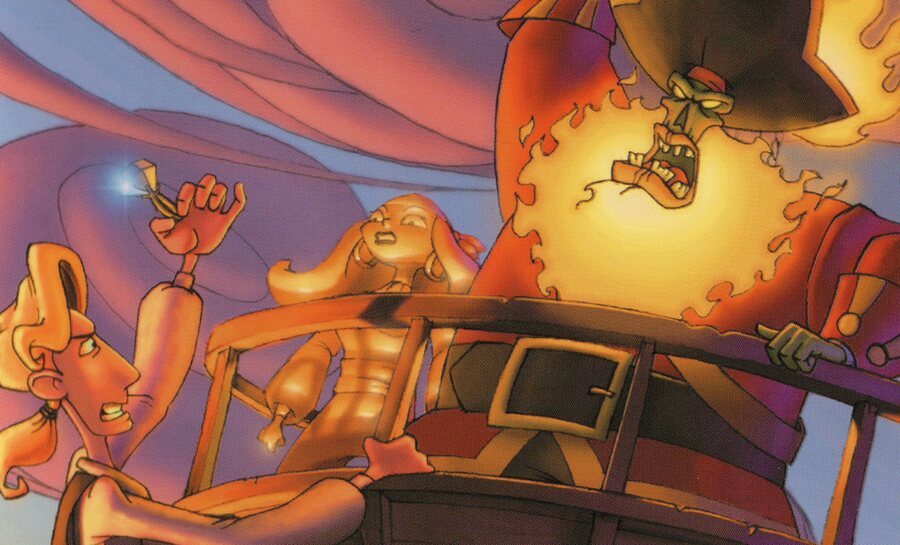

The Curse of Monkey Island (1997)

The fervour for a second Monkey Island sequel was fed by more than just fondness for The Secret of Monkey Island and LeChuck’s Revenge. The latter had concluded on a devilish and divisive cliffhanger. Intensifying the craving for an answer to this sudden mic-drop mystery was the promise that the answer already existed! It became received wisdom among fans that Ron Gilbert had planned a trilogy and that therefore the third game was practically already written. Everyone’s questions were on the brink of being answered if only he could make his game. But he couldn’t because he left LucasArts, where the Monkey Island intellectual property remained.

The '90s-established fan site SCUMMBar.com reveals a long-running obsession with the idea that the title “The Secret of Monkey Island” implied some specific “Secret” that never got revealed – and that Gilbert’s mythical third game would have been an explosive unveiling. So The Curse of Monkey Island – Gilbert having had no part in it – launched to a slavering fan base craving answers but only partly willing to accept them. Talk about tough acts to follow…

This tall order fell to co-leads Jonathan Ackley and Larry Ahern, experienced creators with CVs including Monkey Island 2, Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max and Full Throttle. By any objective measure, they delivered a hit. The Curse of Monkey Island sold hundreds of thousands of copies for millions of dollars and collected strong reviews – now a Metacritic 89. Today’s fans cherish memories of new characters like Murray, who would return in later games. Major lore developments abounded – the fate of Stan, the coffin salesman nailed into one of his display models in LeChuck’s Revenge, was a joyous call-back.

The Curse of Monkey Island maintained the atmosphere but was loose in its design. Where Guybrush had been as uninformed as the player, he now lectured from his logbook. Where improvisation had been the puzzle motif ensuring he was never quite master of his domain, The Curse of Monkey Island brought frustrating specificity: that card won’t jimmy a lock, but another one will; your chisel will pry up that nailed plank, but not those.

The game was short, leaving only a brief plot to be driven by puzzles, and the player was somewhat caged to stop the glorious 640x480 graphics being dished out too soon. But while it lasted, it delivered technicolour, fully-voiced fireworks with deep knowledge of the beloved prequels.

However, The Curse of Monkey Island didn’t scratch the itch of convoluted fan theorists, gasping, “Yes, but what is the secret?” Hard-nosed fans denied that the game was canon, a movement eventually boosted by Gilbert’s 2013 comment that “All the games after Monkey Island 2 don't exist in my Monkey Island universe.” The increasingly rose-tinted, hazy inkling that the truth about Monkey Island was out there in Ron Gilbert’s head was not going to go away.

Escape from Monkey Island (2000)

Monkey Island’s next steps are tied to those of video games entering the 21st century. The golden-age bubble of 2D graphic adventures burst, as too many were bloated, verbose and painfully contrived. Meanwhile, consoles boomed and 3D graphics began to come of age. The notorious 2000 treatise on classic games blog Old Man Murray, “The Death of Adventure Games”, ridiculed the state of the genre with a scathing dismantling of the absurd cat-hair-moustache puzzle from Gabriel Knight 3. Graphic adventures needed to pivot.

Following the trends of the time, LucasArts made Escape from Monkey Island 3D and gave the player direct control of Guybrush, rather than a cursor. Project leads were Michael Stemmle and Sean Clark, who had co-directed 1993’s Sam and Max Hit the Road and worked on other LucasArts adventures including the first Monkey Island. Composer Michael Land was back again, too.

Those links to the classics were there, but times had changed. In hindsight, the luxuriant 640x480 2D art of The Curse of Monkey Island looks like the pinnacle of a certain movement; the bland polygons of Escape from Monkey Island look like a medium still germinating. Characters looked unfamiliar and environments lacked mystery. Controller-friendly interaction enabled release on Sony’s behemoth PlayStation 2, tapping into the increasingly dominant console market, but sales remained weak. The writing – for Monkey Island and the graphic adventure genre – was on the wall.

Escape from Monkey Island played fast and loose with ideas from the other games, while failing to land its own: the careful love/hate balance of Elaine and Guybrush’s relationship descended into an odd aggression; the iconic monkey head from Secret was annexed for the purposes of an unhinged plot; the forced inclusion of something to match insult sword fighting resulted in the extended, flogging-a-dead-joke “Monkey Kombat”.

After The Curse of Monkey Island, the hopes of a story continuing Ron Gilbert’s supposed original plan had looked frail; now, in the wake of Escape from Monkey Island, they’d been crushed.

Tales of Monkey Island (2009)

While Escape from Monkey Island wasn’t badly received by critics (now 86 on Metacritic), the games market wasn’t receptive to the adventure game genre anymore. It was nine years before Tales of Monkey Island arrived, during which time the seas changed in a few vital ways.

The megacorp feel of the booming platform holders in the PS2/Xbox/GameCube era had softened. Console services brought digital distribution to the mainstream, birthing the modern indie scene – a scene where experimentation was less risky. Gamer sensibilities adapted, and niche markets for niche genres started to look like fertile ground for smaller studios.

In 2004, Telltale Games was founded by three former LucasArts developers who wanted to keep making adventure games. Dave Grossman, one of the writing trio on Monkey Islands 1 and 2, joined Telltale in 2005, and Sam & Max Save the World launched its six-episode run in 2006 with input from Steve Purcell, the characters’ creator and original Monkey Island artist. With some Monkey-connected names and a former LucasArts series under their belt, Telltale had the pedigree when they secured the license for 2009’s Tales of Monkey Island.

Like Escape from Monkey Island, Tales was a 3D, controller-friendly game, released across a range of platforms. It sold well and reviewed well – although the Metacritic scores of the Monkey Island series continued slowly to slide, Tales hovering around 80 across its five episodes.

Never, however, had Monkey Island felt so distant from its origins. Epic plot arcs had given way to modular escapades; events and dialogue traded on the characters’ already-divisive traits established since LeChuck’s Revenge, rather than expand them; puzzles seemed modular, plugged into, rather than driving the story. No longer a swashbuckling saga, Monkey Island had become a sitcom.

Return to Monkey Island (2022)

With Disney acquiring LucasArts in 2012, Gilbert’s own enquiries at that time getting knocked back, and the long and winding diversions in plot and lore since 1991, the mythical Ron-already-wrote-it “true” Monkey Island 3 looked impossible. But the less likely it seemed, the harder the last undying flicker of hope – if, if it could happen – would drop jaws with its wonder.

When Ron Gilbert announced Return to Monkey Island in 2022, he did so – as he had promised he would many years before – on April Fool’s day.

However, it’s not exactly a fairytale ending for those old purists. The expectation of pixel art was dashed (and the backlash was so extreme that Gilbert said he would take a step back from talking about the new game). Murray the Skull appeared in the trailer – a character that supposedly “didn’t exist” in Gilbert’s canon. A total retcon at this stage in the series’ legacy was deemed too brutal, too disrespectful. But the fatal blow to the dream of gaming’s ultimate secret reveal was Gilbert’s own blog post a month after announcing Return to Monkey Island:

People talk a lot about Monkey Island 3 as if it was the game I would have made after Monkey Island 2 had I stayed at Lucasfilm.

Here’s the deal.

The totality of that idea was ‘Guybrush chases the demon pirate LeChuck to hell and Stan is there.’ That’s it. That’s all it was.

Suddenly, the mythical Monkey 3, the known-just-not-revealed True And Eternal Secret of the Universe Itself, was gone. With one quick blog post, it went from a longed-for, rose-tinted gossamer of wishes to a debunked figment of misunderstanding.

Is Return to Monkey Island a revival of the past? Right now, the week before release, fans should hope it’s a return to the cutting edge, a return to design principles, a return to perfectly-judged jokes, and a return to indulgent rewards of graphical content for solving open, extended, story-revealing puzzles. The imaginative force of The Secret of Monkey Island provided a fuel reserve that still powers the dreams of fans 32 years later.

Perhaps Return to Monkey Island can be another game for the future.

Return to Monkey Island launches on September 19th, 2022.

Comments 1

Releasing this Monday, already pre-ordered, can't wait

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...