Central Street Memories

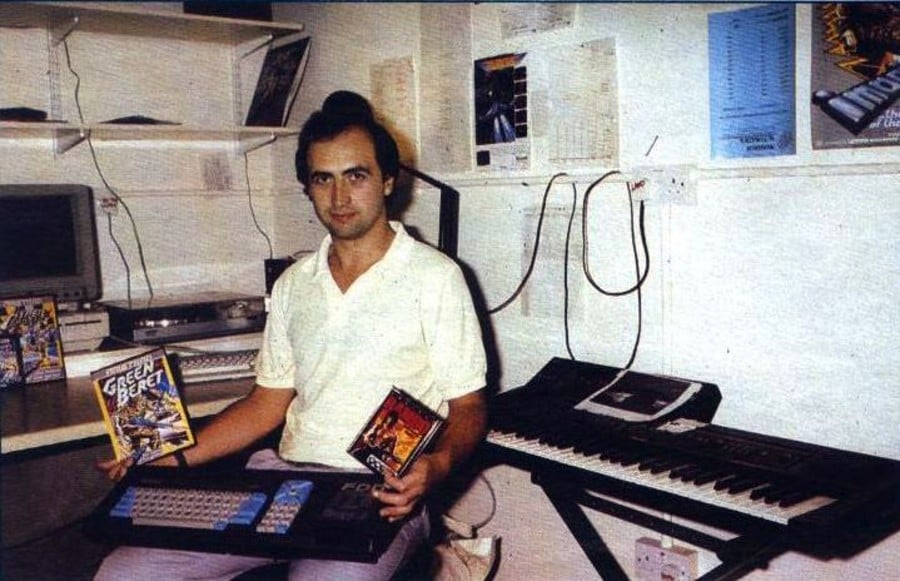

Bill Barna

Bill Barna was among the first wave of programmers hired while Ocean was still situated at Ralli buildings, having previously written a version of Hunchback for the Dragon-32 for the company as a freelancer. At Ocean, he would later go on to work on the Commodore 64 classics Daley Thompson’s Decathlon, Hunchback II: Quasimodo’s Revenge, and Rambo: First Blood Part II, in addition to handling the mastering at the studio and writing the original Ocean Loader.

When we first moved there, it was only the upstairs rooms. We didn’t have "The Dungeon" and there was enough room for the few of us then. Whoever owned the building obviously needed to rent out the office space and we just happened to rent out it out. I don’t think that either Jon Woods or Dave Ward had anything to do with whatever the religious goings-on were.

[Out of the two owners], Dave Ward was pretty much the more outspoken. He was usually the one if there was an interview of some kind, he’d generally be the one who was being interviewed. And he was pretty good in front of a camera. You put him in front of a camera and he was very confident and he could talk about games with the sort of enthusiasm that the rest of us felt working on them. But he had that enthusiasm for the games, as well as it being a good business to be in. Jon Woods was quieter, but both of them were very good with us.

[For example], when we were working on Daley Thompson’s we had a deadline obviously because Daley Thompson was only a day away from winning gold and we still hadn’t finished the game, so we had to get it done pretty quickly.

Daley Thompson’s Decathlon was Track & Field really, which was a Konami Track & Field game. A lot of the ideas came from that, but because it was a Decathlon, it was the same 10 events. Daley Thompson, in fact, was the first-ever — for a British game I believe — sports celebrity endorsement.

Anyway, the magazine adverts on the back pages of magazines were being printed and they cost quite a lot of money, even back then. So Jon Woods decided that he would try and get us to work more or less in shifts, and obviously, we agreed to do it, because we all knew it was quite important. Jon was very generous at the time, and he was offering all sorts of bonuses as incentives to work. We didn’t need the incentives, but it was good that it was there. And then afterward, it was just party time.

I think it was really Daley Thompson's Decathlon that started Ocean onto becoming recognized by everybody. That was the game that started to be noticed. It was in the magazines, it was being talked about on the radio and the television. That's really the one that kickstarted Ocean's rise from Central Street.

Tony Pomfret

Tony Pomfret joined Ocean as a teenager shortly after the company had moved to Central Street. There he worked on Commodore 64 games, including Daley Thompson’s Decathlon, Hunchback II: Quasimodo’s Revenge, Rambo: First Blood Part II, and Mikie, before leaving to join the Liverpool-based company Special FX in 1986.

I actually worked at my father’s shop on Deansgate straight opposite a ginnel that went past the police station and popped out straight in front of the Friends’ Meeting House. So, when a mass of Ocean people came into the shop — obviously it was a computer shop — they were interested, but they were even more interested when they realized that I was a writer. I was writing from the age of 13, and I’d written virtually a full game called Bushfire. It never got completed fully, though, because I got employed by Ocean and then asked to do Daley Thompson’s Decathlon. That and many more!

To begin with, I worked upstairs, not in "The Dungeon". I went in The Dungeon later on, but initially, I was in the offices upstairs. What can I say about Ocean at the time? I found it amazing. I really did. I found it incredible. I found it wonderful. I found it to be a place where I could thrive. When it started off it was just me, Dave Collier, Bill Barna, and Richard Kay. That’s all there was upstairs. Then the dungeon opened and oh my god, flooded. Absolutely flooded. I remember Martin Galway’s first day. I remember so many games that not only Ocean was producing, but I was helping with: Street Hawk, Rambo First Blood (Part II of course), Roland’s Rat Race, and Mikie!

I loved writing Rambo First Blood Part II because it was a full-screen, 8-way scrolling game. I also employed a sprite multiplexer in it, so instead of having 8 sprites, I’d have 16 to 24 sprites running around. It was wicked!

Martin Galway

Martin Galway started off freelancing for Ocean in 1984, memorably contributing the chiptune cover of YMO's 'Rydeen' to the loader for the C64 version of Daley Thompson's Decathlon. He later joined Ocean full-time in January 1985, and in the process became the first in-house musician located at the Central Street office. Over the years, he contributed a ton of music to Ocean's games, including the soundtracks for Rambo: First Blood Part II and Wizball for the Commodore 64.

My school friend Paul Proctor had done a Pacman clone called Eyes - he used to program entire games at home and then delete them! I convinced him to let me sell it and I would get 10% of the money. I looked for the address of Ocean Software on the back of a copy of Personal Computer News, a magazine I bought every week. The status of a company in the biz can be seen by where they advertise - and Ocean was on the back cover of almost every magazine (they must have spent a lot of money on ads).

Anyhow we took the bus into town and tried to get into the Ralli Buildings - but it looked derelict and was puzzling to us. A few weeks later the address had changed on the ads to 6 Central Street, so I telephoned in to make sure we weren't going to waste our bus money again. I got transferred to David Collier, who invited us to come in, so we did. It was definitely all at the "upstairs" location of Central Street. The basement expansion for developers hadn't happened yet, though they used it for warehousing game cassettes.

I brought my disks of BBC music demos that I had built up, and showed that off and Paul showed off his Pacman clone. The office was quite sparsely-equipped, it definitely seemed like they were in the middle of some renovations/paintwork and had just recently moved in. There was a big Ocean sign in the reception sitting along the wall — it hadn't been hung up yet. We also met David Collier, Tony Pomfret, and Richard Kay, who took the time to sit around with us and look at our demo stuff. Christian Urquart was sitting at his desk working away on a Spectrum game and I remember chatting with him but didn't take much interest in our stuff.

Generally speaking, it was a big thrill to meet actual game developers - in high school, you're always arguing with each other about what the best games are out there, and who the best programmers are at school. Here we were with professionals - it felt like we were mixing it up with god-like wizards. I think theoretically Joffa Smith was around at the time but we didn't see him. When it came time for business, Paul and I sat in the large conference room at a huge table with David Ward - this room was also his office - and Ocean offered 300 quid for the game (which Paul accepted), and I later got 30 of that. Paul bought an Epson printer with the money, I think.

Ocean never sold Eyes commercially - so I don't know why they bought it - and Paul and Ocean never worked together after that, not sure why, although perhaps that was when Paul decided to hand-convert Cookie to the BBC and was connected with Rare after that point (that's another story). The Ocean folks were happy to find a musician who lived in Manchester - their current guy David Dunn was in Portsmouth I think - and they offered to retain me for more music work, and gave me a Commodore 64, tape deck, and assembler to take home with me on the bus. This was somewhere between March and May of 1984. Maybe it was during Easter? In theory, we should both have been at school on a weekday! Once our A-Levels were all finished, I was able to devote more time to Ocean and did several games for them that year, and I left college to take a full-time position on staff in January 1985.

I never saw Jon Woods at Ocean until I started full-time. David Ward was my perception of the boss before that. My office location at the very start was simply sharing with David Collier in a larger office - the same office that Bill, Tony, and David had collaborated in to create Daley Thompson's Decathlon in, and the location where I sat down and hand-typed the loading music the prior 1984. I actually moved around a bit as I ended up sitting in with other programmers to add music to their games. Later when they said, "Enough of that, we're not hiring you to just to music all day, that would be ridiculous! You're a proper game programmer and we want you to do the Match Day C64 conversion!" I got an office that Paul Owens had [previously] been in.

For a week or two I stared at the screen, beads of sweat trickling down my forehead as I tried to work out how to get an entire game programmed. Then someone popped their head around the door and said "Can you do the tune from Neverending Story for Canvas?" At that point, they sorta knew I would never make decent headway as a game programmer if I was continually getting borrowed for music work, so they gave up and admitted I was a full-time musician. That might have been around June 1985, and Jon Woods asked me to come down to the nascent developer offices getting built out in the basement, to ask me what I needed for my "sound studio". I just said "A lot of plugs and a worktop space" basically, and drew out the room that became mine and Jonathan Dunn's office. Then I went on vacation to Europe, and when I came back it was all done, and David and Tony Pomfret were halfway through Rambo.

I had a separate room, though it started out as a mere alcove, to which they added a thin wall with windows - so everyone could see in. I was like a zoo animal on display, but I let 'em have it when Jon Woods brought in his old stereo for me one Monday, and I turned up the volume. Generally, the workspace was pleasant, with lots of gorgeous girls walking around, which can be appealing to young men. But there was no AC and it got very hot in the summer. No ventilation of any kind in fact. Had to just open the doors and windows to let oxygen in!

[I have a few stories that I can share]. One morning I came in to work and all my gear was turned upside down. They thought they were so funny! Another... they would fight and tussle in the corridors and wrap a couple of staff up in tape. One time they were discovered by Jon Woods while doing this, and all got a bollocking. We got a bollocking for taking 2.5hr lunch breaks one time too (David Collier was the software manager, pre-Gary Bracey). Basically, it was a very immature time back then.

[There was also another time] electrical workers (who were adding circuits or whatever) accidentally turned off the power to the whole development basement, and we all lost some work. It depended on how often you saved your work... and in my case, I lost an entire morning's worth of work. I was programming the title screen music for Cobra on the Spectrum in Joffa Smith's office, and the strange dev environment he had, using a Tatung Einstein, made me forget to save anything. I had the tune entirely finished, but not saved at all, just sitting in RAM - and the power got turned off. So I had to start again - and I did a different piece of music altogether the 2nd time. I never re-remembered the first tune and it has been lost to history.

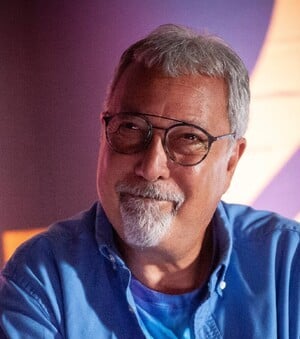

Gary Bracey

Gary Bracey was brought on board at Ocean in 1985, to help manage the development division, and try and turn around a recent run of low-quality games. At Ocean, he oversaw the development department's dramatic expansion, hiring a bunch of mostly young programmers who ended up leading the company's renaissance over the next few years. He was also responsible for making a number of impressive deals for movie licenses, which helped keep Ocean in the spotlight.

I got into video games in my bedroom like most people. I wasn’t terribly technical. I couldn’t program. A little bit on the design side — I thought I had some good ideas for games. But I decided that I wanted video games to be my career, so I borrowed some money from my uncle and I opened the first computer games place in Liverpool, which is I rented a few shelves in the local video library, bought Spectrum Games from a distributor, and sold them.

I knew Jon Woods and David Ward from the old days and Jon had a pub in Liverpool that he used to go to, and I was quite friendly with him and his wife. They used to come in and let me have the odd box of games under the table from Spectrum Games as they were and I used to give them cash. And then, within a year of doing that with the video game library, I’d made enough to open my own shop in the high street in Liverpool, on Allerton Road, which was quite a prestigious high street. I had my own shop and sold computers and games and etc, etc. But that just wasn’t me.

I’m not a retailer by heart. I can’t deal with the public. They annoy me (laughs). So, I was speaking to Jon one day and said, ‘Well, I’m a bit bored’ and he said, ‘We don’t have anyone looking after the software and we are having a few problems with the people who are making the games externally, can you come in? Do you fancy helping us out?’ I said, ‘Yeah, alright, that sounds more up my street.’ So I was taken on as software manager to head up the development because neither David nor John knew anything about games. This was just a business to them. Good at marketing and licensing – all that stuff. Great businessmen. But they weren’t really into games. So they brought in a member of senior management that was interested in games – me – and I was the first person in the company on a management level to be that.

What I noticed was they sort of got licenses like Knight Rider and then farmed it out to an external developer and said, ‘How much to make the game?’ They said, ‘3 grand’ or whatever it was and, ‘Oh, and we want £1000 up front’. And so they gave them £1000 and said, ‘Come back when the game is ready in two months’ time, and of course, the game was never ready because they would just drink the £1000 advance and not do anything until the next milestone was due and then they’d do a bit of work to trigger the next payment. So, no one was actually going out there to see what was up. They were just saying, ‘Okay, here’s the money, deliver it in two months when it’s ready’ and of course, it was never ready. And that happened with a number of projects. So I went down in my car and went down there and saw them and thought this was useless; this was stupid.

[At the time] we did have a number of in-house programmers — Dave Collier, Joffa Smith, all those people – but I realized if we were going to have a grip on quality, then we needed to bring a lot more in-house. So, over the coming year or two, I hired loads of people. And it hugely increased the overhead of the company, but what we did in doing that was we were able to monitor the quality and get the right people and I would attribute the improvement in the product to that. To the fact we brought them in-house, we got really good people – people like Mike Lamb, Dawn Drake, and John Meegan, and loads of them.

[As for the studio] I think from my perspective, it was the energy and the people that made that space what it was. It wasn’t attractive in any sense of the word, but when you bring in all those people, when you bring in that energy, that buzz, people would have ideas, and throw them around. Maybe because it was such a dump, it stirred the creative juices even more and people would bounce ideas off each other. If we were in more sterile offices, I would have questioned whether we would have got the same amount of motivation and commitment, and creative output as we did, being in such squalor.

[At Ocean], there was a time to play and there was a time to work, and I can't recall any conflict between those two. [...] You've got to let off steam, and these guys worked really hard. The clock didn't exist. They'd come into work whenever they strolled in and the clock wouldn't exist. And they'd work through the night and everything else in order to achieve the deadline. I seldom asked people to work late, it was usually done by themselves on their own merit, so I certainly wouldn't begrudge them letting off steam every now and then because of that. It was all about that give and take.

I mean, I wasn't an awful lot older than them, but when you're a certain age, even five years difference is quite a lot, so it gives someone a little bit more gravitas. And, although they were a little bit younger than me, I can't say I was any more mature than they were at the time (laughs). You know, I liked to drink and have a good time.

[One good story I have] is we were out one lunchtime and went past a sports shop and I saw they had a crossbow and I thought, I’ve always wanted to try one of those, let’s get one. And I was out with the lads anyway. So, I bought one and I think they were encouraging me — ‘Yeah, let’s go, go for it, have a go’. And I had nothing better to do with my money obviously, so I brought it back to the office and said, ‘Let’s try this thing out.’ I aimed at the door and it just went straight through. It [almost impaled Brian Flanagan through the head] — I mean, it could have been the biggest disaster ever, can you imagine? But it was just daft, yeah. Funnily enough, I’ve still got it. I’ve never used it since. It was one of those things I got on a whim, tried it, yeah, that’s fun, put it away, and forgot about it.

[There was also] the time I arranged a strip-o-gram for one of our guys who was just turning 18, only years later to discover he was gay (these were very different times back then!).

Lee Cowley

Lee Cowley was Ocean’s first tester. He started at the company back in 1985 and stayed with it (in all its many forms) all the way up until the year 2000. During his time at the company, he not only tested games and worked on Ocean’s budget label The Hit Squad, but also later became a part of the studio’s IT department.

I started at Ocean Software on September 30th, 1985 on a whole £40 per week, when it was based in the center of Manchester on Central Street.

Originally I was placed with Jonathan "Joffa" Smith, playtesting the various games being produced downstairs (in "the dungeon"), as well as answering customer queries via letters and also reviewing any games that people sent in. This also meant brewing up, as well as on one occasion being asked to paint a wall (thanks Colin)! I’m sure our cleaner used bleach to clean the mugs, so they always needed a good rinse. One of the [first] games I remember looking at was Movie by Dusko Dimitrijevic and this was later published under the Imagine label.

I worked in the same room as Jonathan Smith and was able to see him coding, and [also got to] experiment with the games that he wrote. I remember him working on Mikie and getting the sprite of the main character (graphic) to work so that it would walk between the desks correctly. I have very fond memories of him and managed to get to meet him again in later years at a computer convention. Alongside Joffa, there was Paul Owens, David Collier, Tony Pomfret, Bill Barna, Richard Kay, and Martin Galway, and I was lucky enough to play all of the classics before they were released. One of my other early memories was meeting Ian Weatherburn, and Simon Butler as working on The NeverEnding Story. Simon Butler then later joined Ocean. Any others I’ve missed, are purely incidental.

Ocean was always at the forefront of technology, I remember when we received the first Commodore Amiga. This lived in Martin Galway’s room so that he could work on the sound, but I can remember us all being amazed at the graphics of that bouncing ball. This technology continued right up to Ocean receiving a Silicon Graphics PC when again the graphics were spectacular.

In those days, the games were mostly arcade conversions and later moved to film license conversions. I remember Jon Woods sending me down to London to a specific Arcade and checking out some games for him, as well as going to Tottenham Court Road around once a month for a period of time to video and screenshot various computer games to be used in various computer shows and advertising.

One of the last games I worked on was Operation Wolf, and after that I joined Pat Kavanagh on the Hit Squad. Once the Hit Squad was no more I joined the IT department and then IT purchasing.

I met so many great people back in the day, and look back at my Ocean days mostly with fondness. Ocean produced some great games, some of my favourites being Wizball, Arkanoid, Renegade, Addams Family, and a few others. The Christmas parties were great, but we never went to the same place twice (probably because they wouldn’t let us back!)

My only feeling on the later years is that the company was too ahead of its time. Management committed to working on two or three long-term projects, with the only income being Hit Squad as far as I recall. Ultimately, Ocean was purchased by Infogrames in 1996, and my time ended at the company when I was made redundant at the start of 2000.

Mike Lamb

Mike Lamb is one of the many young programmers that Ocean hired in the years following Gary Bracey's appointment. At Ocean, he worked on the ZX Spectrum port of Taito's Renegade, the Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum ports of its sequel Target: Renegade, and various versions of Batman and RoboCop for home computers.

Ocean had some great licenses but their games were getting bad reviews. Gary was hired to fix that and he hired a bunch of us in the summer of 86. I think I applied to an ad in PCW.

My first 6 months there wasn't room at 6 Central St. We had to work across the road until they moved the warehouse out of the basement. We couldn't decide if this was a plus or minus. At some level, we felt a bit left out but on the other hand we got peace and quiet and we could see if someone was coming over. Also, our offices were a bit posher than the basement. After we moved I was in an open-plan area that used to be the warehouse. It was cool but I was happier when I moved into an office with Ronnie Fowles to work on Renegade.

[We] didn’t have much to do with [the Quakers], though I remember hearing that some of them weren’t happy with the games we made. They used to have one of those boards you can put letters on, with peacenik slogans changed every week. “Violence is not the answer,” said the sign outside, and [then] inside we were busy making Robocop and Operation Wolf.

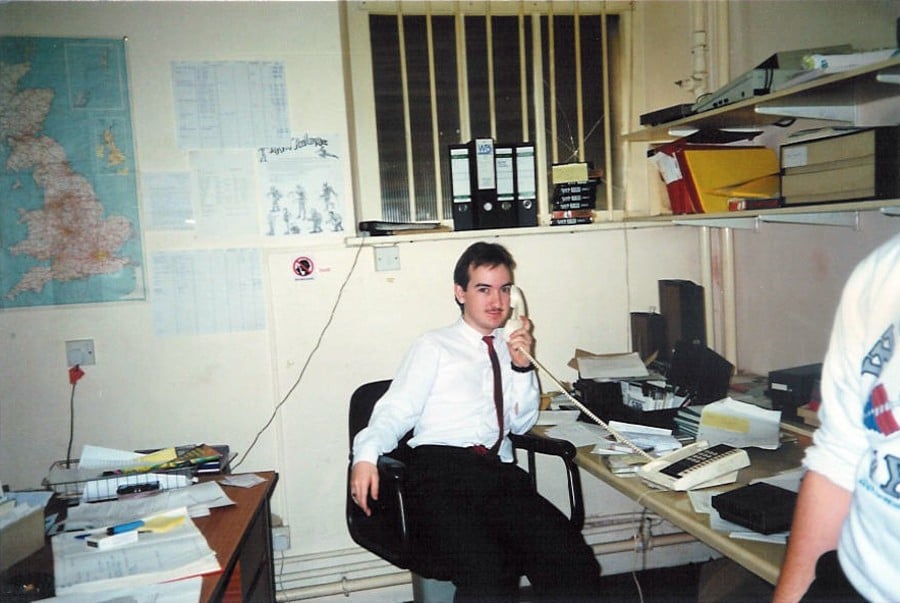

James Higgins

James Higgins started working for Ocean in 1986, originally getting his start developing ports of popular arcade games like Rush’n Attack/Green Beret, Yie Ar Kung-Fu II, and Arkanoid for the Thomson line of home computers in a freelance capacity. After getting a few titles under his belt, he later went on to do programming for a long list of games in-house. This includes the Amstrad CPC port of Arkanoid: Revenge of DOH (his first official in-house project), as well as several video game tie-ins to films like The Untouchables, Total Recall, and The Addams Family on home computers.

I started at Ocean as a freelancer a few months from finishing secondary school. I called the ad and got through to Gary. I was applying as an Amstrad dev. but he didn't seem that interested until I mentioned I could also program 6809 (I had a Dragon 32) before Amstrad. A few days later, I was on my way to Manchester to see this French computer.

My memories of the visit are hazy — I was overwhelmed. I was pretty young/naive. I basically said yes to everything Gary said and was on my way back to Glasgow a few hours later with (I might be misremembering) a Thomson Mo5 with the promise of a contract soon to follow to port Green Beret. I had no idea what I had signed up for. It was ported without source code or graphics. Turns out I'd signed up for versions for the TO7/70 and TO9 too. Luckily very similar. That also involved a flight to Paris to FIL. My first foreign trip. My first flight. My first hotel. It was all very exciting.

This led to ports of Arkanoid and Game Over Parts 1&2. I knew I needed to break away from the bedroom programmer gig and Gary had remembered I could program Amstrad. I was offered Combat School - as a freelancer but in-house. I stayed in a B&B for about three months. It was the first time I worked with someone else. Ronnie Fowles. I was locked in a room with Ronnie and Mike Lamb. I would have struggled to get it done without Mike - he did the end sections. I thought I had blown it. But I was offered in-house and jumped at it. Moved to Manchester shortly after. First day. I was totally unprepared. Turned up with an Ocean holdall and no plan. No place to stay. I had no idea. I found a place the next day.

My first in-house project was Arkanoid 2 for Amstrad. Andy Deacon and Ivan Horn did a Spectrum version. Ivan had done all of the art already. I just had to make it work. Andy and Ivan were a great team on Spectrum I learned a lot from them.

Paul "Paulie" Hughes

Paul "Paulie" Hughes joined Ocean in 1986 as a programmer. At the company, he worked on the technology behind the "Ocean Loader", as well as the copy protection for Ocean’s games (taking over from Bill Barna). He also programmed games like Batman for the Atari ST, and Operation Thunderbolt for the Commodore 64.

Getting the job was equal parts serendipity and a wee bit of nepotism. I’d been writing games since the age of 13, and at 17 I took my first in-house game programming job as the first employee at Software Creations in Manchester. My auntie mentioned this news to her other nephew, who turned out to also be a game programmer; one Mr Dave Collier.

Dave invited me to the basement to have a look around and by the time the tour was over and I’d “talked tech” he asked Gary to offer me a job. The petulant teenager in me quit Creations after two months without a “by your leave” to go for my dream job at Ocean. Not my finest moment in business, but a moment that was pivotal in a 40+ year game programming career that is still going.

Ocean was, in hindsight, making it up as it went along, but back then it led the way; the things we made up became de-facto standards of a burgeoning new industry. [...] It was competitive, but nurturing, stressful but rewarding, and haphazard but organized. I wouldn’t swap that time for the world; I think that’s why so many of us, thirty years on, are still in touch and talk about the days with such fondness.

I moved all over the place, from project to project, at one point when we started console development we moved into a separate secure building around the corner to work on NES, Gameboy, and SNES. My work spaces were minimal: an Atari ST with a luxurious hard drive, a box of disks, a writing pad, and whatever the target platform was (a C64, an NES, or a Spectrum).

[As for any funny or unusual anecdotes], I’m certain it has been told before, but the infamous “bricking up” of the downstairs toilets. Ocean was a building of two stories; upstairs where all the business was run and the basement where the game development took place. After 5 pm the upstairs was generally shut and with that, the toilets too. So Ocean had a deal with the Quakers that owned the building that we could go through a locked (!) fire exit into the church to use the toilets after hours, which, back then, we used a lot as 24, even 48-hour sessions were not uncommon. Long story short, something purportedly happened in those church rooms one evening by a couple of members of staff much to the chagrin of the Quakers. A few weeks later someone nipped to the loo, unlocked the door, and there was a brick wall! Not only could we not go for a wee, but if there had been a fire we would’ve been toast!

Simon Butler

Simon Butler is a video game artist who has been working in the games industry since 1983. In that time, he has contributed to the development of over 300 titles. At the beginning of his career, he was freelancing for companies such as the Liverpool-based Imagine and Denton Designs, but in 1987, he took an in-house role at Ocean Software after receiving an interview offer. At Ocean, he worked on the graphics for numerous projects, including The Addams Family video game for SNES.

When I first entered the industry there was no industry per se. The only company I knew of was Imagine Software. My first encounter with Ocean was when David Ward visited Denton Designs in Liverpool to discuss projects. I was never a fan of any company as such, I was merely doing a job, albeit one that none had ever done before. I worked freelance for four years before moving to in-house work with Ocean. In fact, I had quit the industry in disgust or so I thought when I received a call from Gary Bracey asking me to go to Manchester for an interview.

I was offered a position on the spot the following day and while I couldn't say I admired or adulated Ocean I held them in regard as they were an established name in the industry at that time and seemed capable of offering me the stability which had been lacking to date.

I was in a large office in "the dungeons" at the start of my first stint with Ocean. There were probably eight or more people in the same space; people like John Brandwood, Bill Harbison, Mark Jones Senior, Paul Hughes, Ivan Horn, and Andrew Deakin, Andrew Sleigh, and Colin Porch.

Ocean was very amateurish if truth be told, but that's no slur as the industry was still in its infancy and there was no model for comparison, so people sat at desks and coded or created graphics. There were no swish offices or hints of modernity. It was a basement belonging to the Quaker Church above and as long as we were relatively warm and dry then that was the working environment. The staff however were a completely different kettle of fish. Mostly kids, markedly younger than me, they were a friendly and enthusiastic crowd who were finding their feet in their first jobs and in an industry that had no guidelines.

Ivan Horn

Ivan Horn joined Ocean as an artist in 1987 and contributed art to a bunch of Ocean games over the next 8 years. Some of the games he worked on while at the studio include the various home computer versions of Rambo III, Operation Wolf for Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum, Renegade III: The Final Chapter for Amstrad CPC, MSX, and ZX Spectrum, and RoboCop 2 for ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC.

I'd been working with Andrew Deakin (with whom I worked for most of my time at Ocean) in Devon, where we both grew up and knew each other from school. We'd put together a few budget titles for Budgie, Firebird, and Mastertronic, but there was almost no money in that, so we decided to contact a few of the larger games companies and see if they were looking to hire a coder and artist.

The first interview we had was at Gremlin Graphics, who liked the game we were currently working on (a shameless rip-off of Gargoyle Games' Lightforce) but weren't looking to hire anyone at the time. We were pretty disappointed by that first interview, but when I got home that night, there was a letter there from Ocean, asking the pair of us to come up for an interview.

Within a couple of weeks, we'd visited the great metropolis of Manchester (hey... we were a couple of kids from East Devon), had an interview with Gary Bracey, and had been offered jobs at Ocean. Another week or two later and the pair of us were heading up to Manchester in my old yellow Renault 5, packed to the gills with as much of our stuff as we could cram in. We'd planned to head up in the morning to arrive at the Central Street office sometime in the afternoon but were too excited to wait. So instead, we headed off sometime after midnight and drove through the night, ending up parked outside the entrance at about 7 o’clock, on a damp Tuesday morning waiting for someone to arrive and let us inside.

Back then, Ocean was a pretty good place to work, although by current standards the office was pretty basic, especially the "kitchen", which wasn't much more than a cupboard with a fridge and a kettle in it. Most people I worked with were talented and easy to get along with and the place had a really good social scene. As so many of us were around the same age (late teens or early 20s) and not from Manchester, we hung out together a lot, rather than having friends outside of work to socialize with. For a while at least.

Friday nights were particularly good, with a lot of us (usually 15 or so) heading to the Square Albert pub that was around the corner from the office, for the first couple of hours, before heading off to one of the more studenty pubs and later one of the student clubs (usually "5th Avenue"), to finish off the night.

Ocean obviously changed a lot over the 8 years that I was working there, going from the rather dingy basement in the Central Street office to the freshly converted (and rather swish for the time) warehouse office in Castlefield. However, for most of that time, the work environment was pretty laid back and we got to work on some games which, if not typically very original, were frequently successful, which was nice.

Zach Townsend

Zach Townsend joined Ocean in 1987 as a programmer. While at the company, he worked on a bunch of classic C64 games including Platoon, Batman, Rambo III, and Renegade III: The Final Chapter.

It was a bit basic, open plan, I think we had some kitchen worktop against the wall for a desk, but can't be sure now. But it did the job.

I first got the job at Ocean because I sent them some machine code (assembly language) demos I'd created: one of a fast-scrolling game and one of a character jumping around a rock-type cave, I think. They straight away offered me a job and put me to work.

The game I remember most was probably Platoon, because the game was made up from scratch rather than an arcade license, and there was a fair bit of flexibility at the time as to what the levels consisted of and the gameplay. They were all heavily rushed though, with tight deadlines, so I was slightly envious of the guys that freelanced and had the freedom to do their own thing at their own pace.

Mark R. Jones

Mark R. Jones was the younger of two Mark Jones who worked for the company, which led to his nickname Jr. He started working at Ocean Software in 1987, contributing graphics to titles such as Wizball and Gryzor for the ZX Spectrum, as well as Total Recall for Spectrum, Amiga, and Atari ST. The following is a collection of excerpts taken from his ebook LOAD DIJ DIJ (reprinted with permission) about his time spent at the company.

Down in the programming area, there was very little natural light, just tiny windows at the top of each cordoned-off room which, on the other side, were level with the pavement outside. If you looked up at the windows you could just see people's legs as they walked by. There were game tapes, magazines, joysticks, wires, power supplies, paperwork, and computers piled about everywhere and the place permeated with the aroma of coffee and stale cigarette smoke. [...] A constant background noise consisting of people talking, the tapping of keys, computer music and doors slamming reverberated around the place. [...]

One of the things that made getting a job at Ocean Software so exciting for me was that when I was 14/15 years old a few years back and I'd read a magazine article about a programmer or artist who'd just completed and had their new game released I was in awe. These people were, to me, nearly as famous as pop and film stars! They managed to create these new games that could take you to all sorts of places just by typing things into a computer. Now here I was sitting next to them, talking to them while I made brews, being mates with them and, of course, working with them. Eventually, I'm not sure how long this actually took to happen, but it did, I turned into one of them.

It was totally bizarre. Writers from the magazines I'd bought and read religiously were soon going to be coming in to speak to me, ask me questions about the new games I was involved with and that would then be printed in their magazines and read by games players who were now in the position I used to be in. It was a totally bizarre situation I found myself in.

John Palmer

John Palmer was another one of Ocean’s talented artists. He joined the company in 1987 and went on to work on Rastan Saga, Target Renegade, and Daley Thompson’s Olympic Challenge for Commodore 64; Batman The Movie for Amiga and Atari ST; and The Addams Family: Pugsley’s Scavenger Hunt for SNES. He left the company in 1992, and later worked at studios such as Virgin Interactive, Spiral House, Warthog, and D3t.

I moved from Devon to Manchester to work for Ocean Software in 1987; I was 21 at the time and it was my first full-time job as an artist/animator in the games industry. Although having had experience independently with a few games published before, I never made any money from them, so this was a new experience!

The games development side was downstairs in the basement/cellar/dungeon — an open plan area and many little rooms — with small teams of artists, coders, testers, and other basement-dwelling creatures scattered about. It was pretty dingy really and people could smoke in the office — sounds crazy now but it was commonplace — and we all tended to move about depending on what project you were working on. I remember when I worked on Target Renegade on the C64; I was moved to a room with a coder and another artist who were both working on the same project; they both smoked and I sat between them both. Being a non-smoker, it kind of sucked!

The first game I worked on at Ocean was the C64 version of Rastan Saga, which I believe had already been started before I joined. I only worked on the sprites for that game, I remember they had the original arcade board wired up in a room that we could play and use for reference. The C64 hardware was so limited we couldn't really make a very faithful copy of it but we did the best we could. I guess you could say the same with most of the Arcade conversions in those days really.

It was a productive time at Ocean, and with 5 years at the studio in Manchester, I was lucky enough to work on many published games, including Target Renegade (C64), Daley Thompson’s Olympic Challenge (C64), and Batman The Movie (Amiga). But all in all, it was a good time. Games development was much simpler back then and perhaps more fun...and I also got a free Ocean Mug out of it!

Bill Harbison

Bill Harbison was an artist/animator at Ocean Software who joined the company in 1988. One of the first games he worked on at the Manchester studio was Daley Thompson’s Olympic Challenge for the ZX Spectrum in 1988. He also later went on to do the graphics for Chase H.Q. for ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC, Batman on Amiga and Atari ST, and Jurassic Park for Amiga and DOS, among many other titles.

I knew about them from games that I played Hunchback and things like that, but when I applied for a job there, they were not doing so well. The games that were coming out really weren’t that great and I was quite lucky that my application that wasn’t really an application, it was more like a begging letter, coincided with Gary Bracey starting at the company and getting this bigger team together and obviously focusing on film licenses and that sort of thing.

I think before I had started working there I had been watching stuff on TV, you know, like The Computer Programme and all that stuff that came out on the BBC and I was expecting the people that I was going to be working with to be a bit like them. A bit sort of like older, sweaters, all nicely dressed and all the rest of it and they weren’t. They were all pretty much around my age and like me, so this was like my version of going to college.

The first day that I started I was told I was going to be working on Daley Thompson’s Olympic Challenge, but the actual first thing I did was the loading screen for Robocop on the Spectrum. I think that’s because Gary knew I was quite fast at loading screens. So, whenever he needed a loading screen for a demo — ‘Oh, we need it by the end of today’ — he’d come and ask me to do it.

[One strange memory I have of Ocean] is because it was Central Manchester and because the address was in all the magazines, occasionally you’d just have little boys knocking on the door. They would just turn up in the afternoon and want to know what was going on and so we’d give them a couple of games and send them off.

[Another story is] I know at one point when Gary was out, some [members of staff] were shotgunning cans of Budweiser in his office to the point where it was hitting the ceiling. I think one of the programmers got it wrong and you’re only supposed to pierce the can, open it, and then drink it, but he put the knife straight through his hand and had to go to A&E.

And then the only other thing I can remember is 88/89 when we went down to London for what would have been the computer trade show (I don’t know what it would have been called then). There was a venue where we were going to have our own party there and we were told they had hired Bob Monkhouse for the night. We were like, ‘He’s not turning up, there’s no way that’s true.’

So, we were just sitting around having a good time and all the rest of it and Gary called us into the middle of the room, did this little speech, and then he said, ‘Here’s Bob Monkhouse!’ And Bob Monkhouse walked out onto this tiny, little stage — we’re literally 3ft in front of him — and he just started doing all this stuff about us.

Apparently, he’d been there for a while and he was talking to Gary like, ‘Give me some ideas for who I can talk about. Who can take a joke? Who can’t?’ All that sort of thing. And then he just came out and did like 20 minutes about us. It was weird!

Comments 7

Man, I think you could turn this into a short physical book/mag.

This was really fun to read! I hope to see a similar article covering other companies such as Imagitec Design.

Certainly a big Article, brilliant read. What amazing times they were. These programmer's were like gods to me. Loved OCEAN, used to cut out the stunning box art ads from the magazines and stick on my bedroom wall as a young teenager. No doubt working there at the time would of been my dream job as well.

The batman game was really good

Excellent article, well done!

What a great article 😀 Really nice to read about my heroes from the past 👍

Awesome article. Thank you

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...