Following its original release on the Apple II computer back in 1989, Broderbund and Jordan Mechner's cinematic platforming classic Prince of Persia went on to receive countless ports to other machines. However, very few of these are as well regarded as its 1992 Super Famicom/SNES port from the developer Arsys Software.

Going far beyond just being a simple retread of the Apple II adventure, it ended up expanding the title in a bunch of exciting ways, introducing new bosses (including the six-armed titan Ashura and the female warrior Amazon) and new levels, as well as increasing the time limit from one hour to 120 minutes to make up for all these added features. As a result, I've always been curious to know more about its development, and what went into bringing the title to the Nintendo platform.

In the past, there have been several articles about the different ports of Prince of Persia, as well as an incredible "Making Of" book from its original creator Jordan Mechner, collecting together his journal entries related to the making of the original Apple II game and its aftermath. But firsthand English accounts from those who worked on the Super Famicom/SNES version have practically been non-existent, likely due to the fact the developer Arsys Software is based in Japan. Because of this, earlier in the year, I set out with the help of the Japanese-to-English translator Liz Bushouse, to try and track down some of the individuals who worked on the project, to see if I could tease out any information about the development of this specific version of the game, to document the making of the Super Famicom/SNES classic.

Initially, this proved to be promising, with a former programmer from Arsys responding to a message I sent via LinkedIn, suggesting they'd be up for answering some of my questions. However, nothing eventually came of this, leading me to go back to the drawing board again and send out even more messages to see if we could get a reply from anyone else. A long period of silence then followed, which ultimately ended up lasting until earlier this month, which is when I finally heard back from a Japanese game developer named Keiichi Onogi, who discovered our message in his spam folder.

Onogi is credited on the Super Famicom/SNES version of Prince of Persia as a producer but as he told us, he wasn't actually employed at Arsys Software, but was instead a member of Masaya/Nippon Computer Systems, the Japanese publisher of the game.

As a documenter of video game history himself (he recently interviewed former Nintendo general manager Shinji Hatano in a conversation he plans to publish in the future), he was more than happy to help me out and even assisted in passing along some questions to Keisuke Yasaka, the director of the game (who also worked at Masaya).

As Onogi recalled, in his answers to my questions, the initial conversation regarding doing a Super Famicom port of Prince of Persia came about after Masaya had worked with Arsys Software on a port of the Mega Drive game Star Cruiser back in 1990.

At the time, Arsys had just recently ported Prince of Persia to the PC-98, which was developed for a company called SystemSoft that had acquired the rights to create new titles for the Japanese market from Broderbund.

Onogi told me, "After Star Cruiser, we talked with Arsys about what to develop next. The fact that Arsys had ported Prince of Persia to PC98 at the request of SystemSoft came up during the conversation, and so we were introduced to Henry Yamamoto, who was the president of SystemSoft back then. As I recall, it was Henry Yamamoto who asked Broderbund for the licensing rights to port Prince of Persia to the SFC and Gameboy in Japan."

Just in case you've never played the original Prince of Persia, now would probably be the best time to give you a quick overview on its story and core gameplay.

The main story in Prince of Persia focuses on a classic fight between good and evil, with players taking control of an adventure from a foreign land (often referred to by players as "The Prince"), who has been imprisoned in a dungeon by the Grand Vizier Jaffar. Jaffar has recently seized power from the Sultan, who is away fighting in a foreign war, and has given the Sultan's daughter an ultimatum — marry him or die — before the last sand in the hourglass has fallen. So it is ultimately left to the young stranger to escape the palace dungeons and rescue the princess before it's too late.

In order to do this, players must run, climb, drop, and fight their way through various screens, avoiding Jaffar's soldiers and the palace's deadly traps, with the movements in the original game being based on animations produced using a technique called Rotoscoping, which Mechner had previously used on the Apple II fighting game Karateka.

One of the biggest questions people typically have about the making of Prince of Persia for the Super Famicom/SNES is why the studio decided to change the game so much. In fact, when we reached out the original creator of Prince of Persia Jordan Mechner (who was uninvolved with this project) to see what questions he might have for the team, this was one of the key aspects that he found himself curious about, wondering about what "discussions led to their deciding to expand and deepen the game" and who was responsible for overseeing the project, .

According to Onogi, it was SystemSoft's Henry Yamamoto who was apparently the person who suggested the idea, but this decision was also welcomed by those working at Arsys and Masaya, as they didn't fancy doing just straightforward port of Arsys's previous PC-98 version of the game.

Onogi recalled, "During the discussions to acquire the license, Mr. Henry Yamamoto said, 'If we're going to do this, I'd like to add in original aspects to the SFC version instead of doing a faithful port like the PC-98 version.' Arsys Software was also eager to do that, and had a lot of ideas from when they worked on the PC-98 port. One of the reasons we were able to easily acquire the license was because Arsys would be developing it, and because this was their second time working on Prince of Persia, there was no thought whatsoever that the SFC version would be a simple port."

Talking about his approach, Yasaka, through Onogi, shared with me that the fundamental idea was to keep "the same traps and system from the original", but to alter the design so that the stages "would leave a different impression". This meant adding in new traps, stages, and enemy characters, as well as expanding the time limit and map. Because of all of these changes, he ended up describing the finished version as almost "like a completely new game rather than a simple port."

Reflecting on these changes, meanwhile, Onogi reminisced about his excitement at seeing the changes the team was making, revealing, "Every time the ROM was updated, Arsys would add new elements, and whatever we discussed on the phone (the only way to keep in contact back then was through phone calls) would be added to the next ROM.

"All of the new content was really fun, so the project had a lot of momentum and excitement behind it. Arsys Software really had a thing for movie-like segments, like the scene right before the credits that shows off all the memorable spots from each stage."

Of course, with the team making so many changes, there were some worries from those working on this new version of the game over what the original creator might think, so Onogi told me he made the effort to travel to the US to meet with Mechner about potentially consulting and signing off on any alterations they made, though ultimately this never ended up happening, with someone else at Broderbund stepping in as a contact.

"So much ended up being changed that we figured it'd be only natural for the original creator to get upset if he thought we went too far," said Onogi. "So I went to America to ask for Mr. Mechner's supervision, bringing a video of the gameplay that we shot with a camera, as well as enlarged photos (I think close to 400 of them). I can't remember the name of the person I met then — I don't think it was Doug Carlston or Brian Eheler. But I ended up returning to Japan without seeing Mr. Mechner."

Thoughts about what Mechner might make of the game weren't the only concerns the team had to deal with, however, regarding the changes they were making to the title, with Onogi also recalling issues with the ROM size, which he believed may have forced the team to have to cut back in some areas.

"I heard from Mr. Yasaka that Arsys had a lot of trouble recreating Prince of Persia's iconic smooth animation, because the SFC had very limited VRAM," Onogi said. "And because our main goal was to surpass the original game, the volume naturally went up. I'm sure we had to cut some ideas because of the space on the ROM, but for the most part we compensated for that issue through clever design and technology. The puzzles and mechanics for navigating the map are two examples of that. I think development itself came to an end without extending the deadline too much. But I went to Sasebo a number of times during development, so I'm sure there were plenty of problems to solve."

In addition to these features, which were likely cut due to the ROM size, there were also others areas where elements of the game were removed for other reasons too.

The Super Famicom/SNES version of Prince of Persia, for instance, like the many other ports of the game before it, followed the series' tradition of featuring a lot of unique death animations, with players being able to see the Prince being crushed, impaled, and even burned. In an earlier version of the game, according to Onogi, these were originally meant to be a lot more graphic. However, they eventually had to be toned down after Nintendo complained about the more graphic death scenes.

Some evidence of this can be found on the website The Cutting Room Floor, where unused graphics were discovered in the game's files for a beheading animation and a different version of the spike trap death, featuring visible blood.

"There were similar things in the PC-98 version," said Onogi, "Where blood would spray from spikes or guillotines, or his torso would be cut in two. We added even more to the SFC version, like a scene where a rotating blade cuts his head off, and one where he's burnt to death. Prince of Persia is a difficult game, so the protagonist dies a lot. Because of that, we paid special attention to the death scenes. Thinking back now, it's possible we got carried away.

"Nintendo had to check over it before it was released, and they requested that we edit the particularly brutal scenes, so those got taken out. I don't remember why we added them, because we should've known that they'd be rejected (Nintendo was very strict back then and didn't allow any depictions of blood). Maybe we thought there was a chance they'd get waved through."

The Super Famicom version of Prince of Persia was eventually released in Japan in the Summer of 1992, with the North American version for the SNES releasing later that same year, followed by a European version in 1993. However, in the UK, import reviews of the game already began to surface as early as August 1992, with the British publication Mean Machines giving the port 93% in Issue 23 of the magazine.

In this review, one of Mean Machines' reviewers Rich Leadbetter (who may know now for his work on Digital Foundry) described the SNES version of the game as "something else", praising its "spruced up" graphics, "superior animation", and "stunning backgrounds", as well as the additional levels that had been introduced. Meanwhile, his fellow reviewer Jaz Rignall backed him up on the quality of the port, stating that he "played it virtually non-stop for an entire weekend" and that though it proved to be "highly challenging" the gameplay was just so good that he kept "sticking at it to see what’s around the next corner".

Interestingly, while chatting with Onogi, this topic of the game's difficulty actually did come up, with the developer admitting after watching videos of the game on YouTube, "I'm honestly not sure I could beat it myself. I think I must've just watched Mr. Yasaka play it back during development. It isn't a fast-paced action game, but rather one where you have to think carefully to proceed (and with a time limit!)."

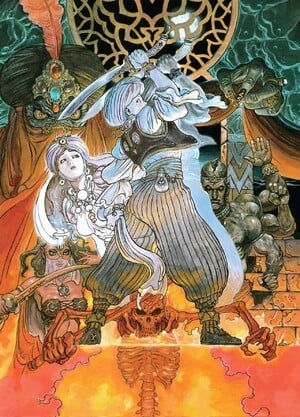

Prince of Persia's super smooth animations and challenging gameplay aren't the elements related to the release that are worthy of praise, with the Japanese and European versions of the game also featuring what I'd describe as one of my favourite pieces of box art ever, courtesy of the famous video game artist Katsuya Terada. According to Onogi, he unfortunately wasn't around during this late stage in the game's development when this box art was eventually commissioned, so once again he reached out to Yasaka on my behalf to discover more about its origins.

"The way that came about," Keisuke Yasaka told Onogi, "Is I asked my graphic designer friend, Tomoharu Saito, 'Are there any artists who are gaining popularity right now?' He gave me a few different names, and the one that left the biggest impression was Mr. Katsuya Terada, whose work I enjoyed very much. I immediately reached out to him, and he happily agreed to take on the assignment.

"I told him that we wanted the protagonist in the center, with Jafar and enemy characters all around him, as well as the captured princess, like a character introduction composition," he continued. "I also told him the major story points, like that the protagonist has a doppelganger and the scene where the mouse comes to the rescue, and that we wanted to convey the game's huge variety of stuff and its sense of adventure.

"Later, Mr. Terada faxed me the rough design, which included everything I had mentioned, and even though it was a rough illustration, it was really well done and got me excited imagining the finished product. I didn't have to request any particular changes, and he went right into working on the real thing."

When looking back on the development of the Super Famicom / SNES version of the game today, Onogi seems to view the title as a special moment in his career, and one that had a sizeable impact on him.

Today, he now works at a place called NJ Holdings, which is the parent company of studios like tri-Ace and various other long-established Japanese game development companies. However, without Prince of Persia and his collaboration with Arsys, he suspects his career might have ended up going in a completely different direction.

"The SFC version of Prince of Persia never would've come into existence if we hadn't met Arsys Software," Onogi told me, "And I think my game career would've been different too had I not met them. It also probably would've been a totally different game had we not received permission from Broderbund to make those changes."

As for Keisuke Yasaka, it appears he continued working in games for a number of years following the release of Prince of Persia, racking up a diverse list of credits on a number of mostly Japanese-exclusive titles.