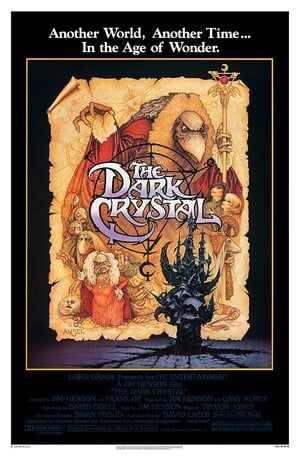

Time Extension: It would be interesting to hear about The Dark Crystal. Ken posted a clip recently of a news broadcast that shows Jim Henson looking over his shoulder while showing off the game. I’m wondering, how was it collaborating with Jim Henson?

Roberta Williams: That was interesting. That was my first experience working with, I don’t know how you might put it, sort of a celebrity kind of thing and a corporation: Jim Henson Productions or whatever they were. Well, how do I explain how that went…

I didn’t report directly to Jim Henson. He assigned someone to work with me by the name of Christopher Cerf. The Cerf family is a very, very big New York City family. Bennett Cerf started the big publishing company Random House in New York City, so he was a big deal, and his son Christopher was working at the time with Jim Henson.

So Jim Henson assigned Christopher Cerf to work with me and I had never really worked with anyone else at this point. Everything was always mine, whatever I wanted, which probably sounds very funny to you because development is big now and teams of people do it. So, I started working with Chris and he gave me all of the scripts and all of the research and all of this stuff that the Dark Crystal movie people had put together and I got three, four, five notebooks of research.

They had done research on planets and the universe and different kind of alien beings that could live out there and then what they were. There were notebooks about ‘And now they live on this planet and here’s the atmosphere of the planet', almost from a scientific standpoint, and then descriptions of the creatures that live there and all about their environment. It was like, you know, Tolkien or something. They had planned out just in this minute detail the lives of these creatures that live on this planet and the environment of the planet and the universe and where it is.

I remember going through it and going, ‘Oh my god, I don’t even know where to begin to get through all this stuff’ and they want it pretty quickly because the movie is going to come out in like six months, or something like that. I didn’t even know where to begin. I remember talking to Chris Cerf and we got it sorted out, I got the game designed, and everything, but there was a funny altercation between him and I in that he didn't understand how I work and how you take a complex story and put it into a game.

A movie is linear. When you read a book, when you watch a movie, it’s linear. You have no control over the story. You have to read it or you watch it; that’s it. But when you’re playing a game, you’re deciding for the most part where you want to go and what you want to do. And that’s the goal! So, he didn't understand how to take that linear story and break it down into parts that would be interactive and how you do that and still maintain the story. […] He, like his father, coming from Random House was a writer, and a writer does a linear story. That’s what you do. You write a book.

So, we had some arguments about that; I won. But then, finally, with my adventure games, I always write all the messages, because that’s the clues you get while playing the game. That’s what tells you what you’re seeing and the feedback that you get from it. So, I wrote all of the messages, because that’s what I do, that’s what I did, and I turned them in to Christopher Cerf, and he rewrote all of my messages. All of them.

He sent them back to me and said, ‘Okay, here it is, here’s all the dialogue, here are all the messages.’ I read them and I said, ‘These aren’t my messages, you rewrote all my messages.’ And he said, ‘Well, I just like to clean them up a little bit, make them a little better, you know.’ I was very angry. I was younger then too. I was only 26 years old – still a little bit volatile. I said, ‘Well, that’s my job!’ And I went back and put all my messages back.

I said, ‘That’s it, we’re doing it this way or I’m out.’ He went to Jim Henson and they discussed and they said, ‘Okay, you can do it the way you want.’ And that was it. He was kind of out of it, and we sold the game and it did pretty good.

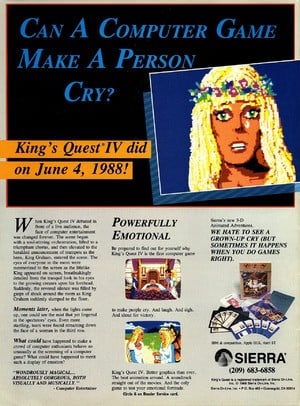

Time Extension: King’s Quest IV was released around the time Sierra was going public. It was also the first game to use the SCI engine. Al Lowe previously told me that there were a lot of issues with that game and getting it out the door. Do you remember much about the development of the game?

Roberta Williams: There were always issues with every one of them and getting them out the door. There were always issues. [But] of all the King’s Quests, I think that one is the strongest in my mind, partly because it has a female protagonist, avatar, ego, whatever you want to call it that we used.

The issue surrounding that – I mean, there probably were some programming issues too because of switching to SCI — was that many in the company were against me having a female protagonist because they thought the whole idea was the computer game industry was more male-oriented.

That was what I was told: that most of the game players were male. And it's true, most of them were. They probably still are to this day, but definitely, a lot of women and girls play video games today. Of course, they do. And there are so many different kinds of choices now for what you want to play; you’ve got the choice. Back then, most computer games were geared more towards males in society who wanted to play games or what might most appeal to a male. But I would get fan mail – there was no internet, no social media, none of that – but we got letters and there were some computer magazines around and what was written about my games, there were clearly a lot of women and girls who were playing my games, not just boys and men.

I got a lot of letters from parents telling me how their daughters and their girls just loved my games, so by the time I was going to write the fourth one, it was just obvious that there was a bigger audience out there, besides just young men. There were girls [playing games]. And I honestly did not think that it was going to matter. There was nothing in my mind that said, if you’re going to be playing a girl, there’s going to be guys like ‘I don’t want to play that’. I did not think that would ever happen, and I was right. It didn’t. Not even at all. No, it just did not happen. I believed that, and Sierra, they were after me.

The programmers, marketing, and sales teams were going to Ken and saying, ‘Tell her not to do that’. And he tried! Very timidly, he tried. And I said, ‘No, it’s time. I’m going to do it. I want to do it.’ And that game, King’s Quest IV, sold twice as much as the prior three. It was huge and another thing was it got a lot of attention out there because of it too. So it had the marketing advantage.

Time Extension: The interesting thing I heard from various people who worked in the industry at the time was even if a game did particularly well in focus-testing with women, they wouldn’t usually advertise to that group. They would always be like, ‘This game is testing really well with women, but let’s still include exclusively boys in the advert’. It’s really bizarre to think that.

Roberta Williams: That was bizarre! I really think King’s Quest IV with Rosella really did open up that. It really opened up everybody’s eyes like ‘Girls like to play computer games too.’ It opened their eyes. That’s why King’s Quest IV does have a special place in my heart and I remember it a whole lot better than the other ones.

Time Extension: Something I have to ask Ken is a question about Sierra Network, which was Sierra's online gaming service that launched in the early '90s. Could you talk about the origins of that? Because it seems like such an ahead of its time concept.

Ken Williams: I had a grandmother at the time, and I happened to be talking to her or thinking of her, and I had this inspiration. I mean, the whole mission statement was 'Wouldn’t it be cool if I could put senior citizens together to play card games against each other at home 24 hours a day, 7 days a week?' And in fact, what I was thinking at the time wasn’t a computer, I wanted to make something that was VCR-size, like a set-top box, that didn’t do anything but link people together for playing cards across the internet.

I made up a little physical mock-up and I called it Constant Companion and I went to all the big hardware companies and telecommunications companies. Remember, there was no internet at the time; no one had thought of an internet. There was no such thing as a network. But I had kind of had this vision for this thing called the Constant Companion box. We could sell it for $99 or $199 and charge them a subscription fee and target senior citizens.

It was a pretty strange product, but I knew if I could get it in there, I could kind of broaden it and start doing more exciting games. So I went to the hardware companies, and NEC was a big hardware company at the time and they gave me 80 computers, and Sprint was a big telecommunications company at the time and they provided us a network, and then I provided all the software. Then we went to work on the Constant Companion and we actually built it and had it playing. There was no network; we did our own little server room, but the computers were in the room of 80 people aged 80 and over and we linked them together.

It was the first time that anything like that had ever been done. At the time, it was 2400 baud modems – actually, it was even 300 baud modems and 1200 baud modems, which is so slow you can see text go across the screen. But we did it and they fell in love. When I knew we had a winner was when our servers were constantly crashing. They would overheat. It was in the early days. It was pretty primitive, but the seniors would sit there and just dial the phone over and over and over again because they thought it was cool and we made it easy enough. It felt right, and they were addicted. It was a way for seniors to meet each other. Now there’s Facebook and all these things and it’s become a way of life, but in those days a lot of them were just stuck at home, they couldn’t go anywhere. And so, this way they were all meeting people and making friends.

Then Warren Buffett and Bill Gates kind of got onto it and started playing Bridge and started telling other people about it. And then we broadened it and I started adding flight simulators and gambling games, and we added games for little kids. We had a game called Boogers that was really cute, we had fantasy roleplaying games, and we had dogfighting. We managed to get it up to 100 paying subscribers, at which point we had both the CEOs of AT&T and Microsoft's Bill Gates personally lobbying me to partner it. We wound up partnering with AT&T and that basically shut it down

AT&T said, ‘Let’s just stop everything — stop marketing it, stop building on it — and flip it over to the internet. I wouldn’t have done that. I would have done kind of a smooth transition, but somehow, they never ever got it running on the internet. It was just stupid. It was the greatest frustration of my life. We were a public company and we were losing probably a million dollars a month on it. And we couldn’t afford to keep doing that. [...] I still consider it the greatest thing I ever did and it preceded the internet [though], and I remember Bill Gates saying, when they were just starting up a project to do MSN, he was thinking about dumping it and using our system. History would have been very different. We should have sold to Microsoft instead of AT&T, but it's 20/20 hindsight. Our lives turned out good and I’m not complaining.

Comments 3

I recognized the name Cerf right away from having seen old episodes of What's My Line? from the '50s on television where Bennett Cerf was often a panelist. I have a feeling the rewrites for the Dark Crystal game were quite extensive, especially during a time when gaming was still new to so many people. Very interesting to read and it's nice that they were able to go down that path and find the success that they did with it. And regarding King's Quest 4, when it was released it was still early enough to assume male players wouldn't want to play as a female character. This game wouldn't be far behind Metroid and Phantasy Star that all helped to change that, and show that if the game is good, it didn't really matter, or could even be a better choice.

I absolutely adore Ken and Roberta! They are legends, give great interviews, and they are by all accounts very nice people. They made some fantastic games, too!

@JackGYarwood if I may point out a minor yet significant typo: I believe the computer Ken is referring to when he talked about going to Japan was the NEC 9801, sometimes called the PC-98, not the "NES 9801." Lest someone confuse it with the Famicom xD

@JJtheTexan Fixed! Appreciate you pointing it out

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...