It’s remarkable to think that many people under the age of about 30 might never have seen a LaserDisc in the flesh, as it were – and they might not even be aware of the existence of this now outdated technology. Yet, for a brief period in the 1980s, it looked like these shiny, LP-sized discs could be the future.

MCA and Philips developed the technology back in the 1970s, and they released their videodisc system under the name of DiscoVision in 1978 – about two years after the debut of VHS tapes, and some four years before the first CDs appeared. Pioneer then bought a majority stake in the format in 1980 and renamed it LaserDisc.

The LaserDisc was immediately plunged into the home video format wars, up against JVC’s VHS and Sony’s Betamax (alongside less well-known combatants such as Video 2000, CED and VHD). The key advantage of LaserDiscs was that they provided a much sharper picture than VHS or Betamax, as well as the fact that users could skip to any part of a movie almost instantly, rather than laboriously winding backwards and forwards through a tape.

However, they were limited by their relatively small storage capacity. Whereas a VHS tape could hold around three hours of video, early LaserDiscs were limited to just 30 minutes per side, later increased to 60 minutes per side. That meant having to flip or change the disc several times if you wanted to watch a long-ish movie.

However, probably the biggest issue was that, unlike VHS, you couldn’t record onto a LaserDisc, thus denying consumers the pleasure and convenience of taping shows off the telly. That, combined with the high price of LaserDisc players and discs compared with VHS, ensured that the format only ever gained a niche audience – mostly with cinephiles who prized pristine picture quality over convenience. In addition, LaserDiscs (and LaserDisc players) cost considerably more than VHS tapes, with the latter gradually decreasing in price as their popularity allowed more efficient mass production.

It wasn’t long before game developers began considering the possibilities that LaserDiscs afforded. Possibly the first ever game to use a LaserDisc player was an arcade machine called Quarter Horse. Made by Electro-Sport, Inc., it was a two-player game where each player made bets on a horse race, after which a clip of a real horse race was played to show who won (you can see a video of a later version of the game here). Although it’s impossible to track down an exact release date for the machine, most sources agree that it came out sometime in 1981, and several different models were in production for years afterwards.

The January 1982 issue of Creative Computing featured instructions on how to make your own LaserDisc game based on the 1977 disaster movie Rollercoaster. It took the form of an adventure game, where the player had to move from scene to scene and make decisions to help stop the rollercoaster track from being blown up by a bomb, with footage from the movie playing at various points. However, it seems unlikely that the game was played by many people, seeing as it involved typing in pages and pages of code into an Apple II computer, then linking it up to a LaserDisc player using an Aurora Systems Video Controller, and finally owning a copy of the movie Rollercoaster on LaserDisc. Considering that the total cost of all of that equipment would have been around $2,000 in 1982, this is a game that would have been accessible to only a very few.

Another piece of early LaserDisc entertainment was the LaserTour exercise bike made by Perceptronics and released in 1982. This enormous machine featured a 45-inch rear-projection monitor hooked up to a wonderfully chunky ‘industrial quality’ LaserDisc player, which showed images of roads (and even a rollercoaster) as you peddled along on the attached Lifecycle exercise bike. It might be stretching the point to call this machine a ‘game’, however – even if it did foreshadow the rise of modern exercise games – and seeing as it cost a whopping $20,000, the equivalent of nearly $62,000 today, it’s unlikely to have found its way into many people’s homes.

Sega’s Astron Belt is often cited as the game that sparked LaserDisc fever in the games industry. First unveiled at the Amusement Machine Show in Tokyo in September 1982 and later displayed at the US Amusement & Music Operators Association in November, it caused a storm with its head-turning graphics. An on-rails shooter, it overlaid a 2D sprite of the player’s spaceship on top of LaserDisc video footage of enemy craft swooping in from all angles, and shooting an enemy ship prompted a ridiculously over-the-top screen-filling explosion. In a time when computer graphics were limited to blocky sprites in a handful of colours, Astron Belt looked like something beamed in from the future.

Astron Belt landed in Japanese arcades in March 1983 and became an instant hit. But it wasn’t released in the United States until October, meaning it was beaten to market by probably the most famous LaserDisc game of the all: Dragon’s Lair. Released in June 1983, it was a collaboration between game designer Rick Dyer and animator Don Bluth, and saw players take control of Dirk the Daring on a mission to rescue Princess Daphne from the clutches of the evil dragon Singe.

Bluth had previously worked at Disney but left with a group of other disgruntled Disney animators to form Don Bluth Productions in 1979, subsequently releasing the animated feature film The Secret of NIMH in 1982 to critical praise but box-office disappointment (it didn’t help that the movie was up against E.T. in theatres). Bluth’s company provided exquisite animation for Dragon’s Lair that drew admiring gazes from arcade goers across the US – a field test of the cabinet drew crowds of over 200 people, and arcade owners reported recouping the cost of the machine within a week. For the first time, you could actually play a cartoon, and it blew people’s minds.

Dragon’s Lair arrived just as the game industry was in the grip of the 1983 US video game crash, when sales of consoles were plummeting and arcade revenues had begun a downward spiral. For a short while at least, LaserDisc looked like it might be the saviour of the industry. Over the next couple of years, a slew of high-profile LaserDisc games appeared in arcades.

Many of them followed the format laid down by Dragon’s Lair, using what nowadays we would call QTEs (quick-time events), although that term wasn’t coined until the release of Shenmue in 1999. At certain points in the game, the player would have to react quickly to events on screen, yanking the joystick in a particular direction or tapping a button to make it safely to the next scene. Pressing the wrong input or failing to react quickly enough would typically prompt an elaborate death animation.

Cliff Hanger (Stern Electronics, 1983) was one of the first games after Dragon’s Lair to follow this format. Rather than going to the trouble and expense of creating their own bespoke animation, as Rick Dyer and Don Bluth had done for Dragon’s Lair, Stern instead simply licensed the use of two Lupin III movies: The Mystery of Mamo (1978) and The Castle of Caligostro (1979, directed by the legendary Hayao Miyazaki). Lupin III was unknown in the US at the time, so Stern simply renamed the character ‘Cliff’. If the player fails in the game, a rather macabre cut scene plays showing Cliff being hanged (hence the name, one supposes), although there was an option on the board to turn this off.

Japanese developers arguably perfected the Dragon’s Lair formula of marrying beautiful bespoke animation with QTEs. Cobra Command (Data East, 1984), Ninja Hayate (Taito, 1984), Super Don Quix-ote (Universal, 1984), Road Blaster (Data East, 1985) and Time Gal (Taito, 1985) all featured truly gorgeous and thrilling animation, making them just as much fun to watch as to play. Konami also got in on the act with Badlands (1984), although the animation in this quick-fire Wild West shooter is nowhere near the quality of games like Cobra Command or Road Blaster. That said, it does feature some endearingly comical failure screens, such as the main character being stretchered off in bandages – and it also features dinosaurs at one point, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

Other games followed Astron Belt’s formula of layering 2D sprites over LaserDisc video footage. M.A.C.H. 3 (Gottlieb, 1983) featured a pixelated jet fighter swooping through real-life clouds and canyons, while Firefox (Atari, 1984) used footage from the Clint Eastwood film of the same name about a hi-tech military jet. Star Rider (Williams, 1983), which is now incredibly rare, was a motorcycle racing game that overlaid sprites over impressive CGI footage which was painstakingly generated, one frame at a time, by top-of-the-line computers (there’s an interesting chat with the game’s programmer about how it was done in this video). Meanwhile, Bega’s Battle (Data East, 1983; known as Genma Taisen in Japan) was a very early LaserDisc title that interchanged sprite-based shooting sections with footage taken from the movie Harmagedon: Genma Taisen, making it one of the first games to feature cinematic cut scenes.

One LaserDisc game that truly stood on its own, however, was Cube Quest, released by Simutrek in 1983. This shoot ‘em up was one of the first ever arcade games to feature-filled 3D polygons, which were overlaid on some wonderfully trippy animated backgrounds, and accompanied by somewhat ethereal sound effects. It feels like a cross between Rez and Jeff Minter’s Tempest 2000, and remains one of the overlooked gems of the LaserDisc era.

Rick Dyer continued to champion the LaserDisc format after the debut of Dragon’s Lair, releasing the sci-fi-themed follow-up Space Ace in 1984, again with animation by Don Bluth’s studio. But Dyer also had plans to take LaserDisc games into the home. His company, Rick Dyer Industries (RDI) began work on a LaserDisc console called Halcyon, named after the murderous computer in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. Like the computer in the film, Halcyon could talk and recognise voice commands. Well, sort of. This was a long, long time before the rise of Alexa and Siri, and footage from the time shows the machine struggling to recognise even simple words.

The Halcyon was set to be released in 1985, but RDI went bankrupt just as it was due to hit shop shelves. Anecdotal reports suggest the company’s backers pulled out – most likely because the console was set to retail for around $2,500, putting it far beyond the reach of most consumers. A handful of Halcyon prototypes survive, however, making it one of the rarest and most prized consoles for collectors. Of the half-dozen games set to be released for the machine, only two are known to have been finished: an NFL Football game, and Thayer’s Quest, a sort-of RPG that featured branching paths and animated cut scenes. Thayer’s Quest did end up being released in arcades in a cabinet featuring a full keyboard.

By 1985, the LaserDisc game fad had truly faded. Players soon realised that for all their fancy graphics, most LaserDisc games were incredibly shallow, often relying on simple trial and error. And arcade owners were put off by the relatively high cost of the machines, as well as their reputation for unreliability: the LaserDisc players were prone to overheating, and the near-constant disc accessing required to make the games work quickly wore out the components.

But the LaserDisc saw an unlikely resurgence in the early nineties, just as arcades began thriving once more following the late-eighties lull. American Laser Games released Mad Dog McCree in 1990 to great success, pairing live-action video of Wild West outlaws with light-gun shooting. The company had previously created light-gun systems for training police officers, and they used the same technology for Mad Dog, with some initial models pairing a LaserDisc player with two Commodore Amiga 500 boards (later versions switched to using other technology, such as modified 3DO consoles). American Laser Games followed up the success of Mad Dog McCree with a whole slew of light-gun games, including Who Shot Johnny Rock? (1991), Space Pirates (1992), Mad Dog II: The Lost Gold (1992), Crime Patrol (1993), Crime Patrol 2: Drug Wars (1993), The Last Bounty Hunter (1994) and Fast Draw Showdown (1994).

Rick Dyer also found his way back to LaserDisc games, designing the holographic Time Traveler, which was released in arcades by Sega in 1991. The game featured live-action footage of actors against a black backdrop and used a curved mirror to make it appear as if the actors were floating above the top of the screen. But it used the same, now somewhat tired QTE gameplay as Dragon’s Lair, and the sheer expense and size of the machine – combined with competition from the newly released Street Fighter II – meant it quickly faded into obscurity. A long-awaited sequel to Dragon’s Lair – Dragon’s Lair II: Time Warp – was also released in arcades in 1991, but it couldn’t recapture anything like the buzz that surrounded the first game.

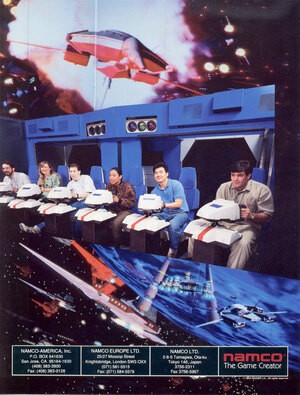

Arcade LaserDisc games arguably reached their peak with the debut of Galaxian 3: Project Dragoon by Namco. Designed for Expo ’90 in Japan, it was more of a theme park ride than an arcade game, and seated 28 players, each with their own gun for shooting down enemy spacecraft. The machine was housed in a circular room with a wraparound screen, and the central hydraulic platform that players sat on bucked and tipped as the game progressed. The game itself consists of LaserDisc footage overlaid with 3D polygons.

In 1992, Galaxian 3 was moved to Namco’s Wonder Eggs theme park (yes, Namco had a theme park), and a handful of smaller, 16-player versions of the game were made and sent to arcades worldwide. Namco also developed a little-known sequel to Galaxian 3 called Attack of the Zolgear, which was sold as a conversion kit for the arcade machine and was released in 1994.

Eventually, we also got a LaserDisc home console. The Pioneer LaserActive was released in Japan and the United States in 1993, just at the peak of the multimedia boom. Companies had been falling over themselves to take advantage of CD-ROM technology, offering machines like the Commodore CDTV, Philips CD-i and 3DO, which would host educational content such as encyclopaedias as well as playing video games – and now Pioneer joined them. The LaserActive could run CDs as well as LaserDiscs, and in addition to several edutainment titles, such as Quiz Econosaurus, it received conversions of LaserDisc arcade games like Road Blaster and Time Gal.

Most interestingly, it was offered with several optional hardware add-ons called ‘PACs’. The Sega PAC came with a Mega Drive controller and allowed users to play Mega Drive cartridges and Mega CD games, while the NEC PAC came with a PC Engine controller and allowed the use of PC Engine Hu-Cards and CDs. There was also a Karaoke PAC that enabled you to plug in two microphones and a Computer Interface PAC that let you hook the LaserActive up to a computer. Finally, the LaserActive 3D goggles were sold separately and used an active shutter 3D system to generate 3D images for half a dozen LaserActive titles, including 3D Museum and Virtual Australia.

Of course, this was all incredibly expensive, which is partly why the LaserActive is now a mere footnote in gaming history. The basic machine cost $970 at launch (the equivalent of around $2,000 today), and the NEC PAC and Sega PAC cost a whopping $600 each. The high price, combined with a limited software library, meant the LaserActive disappeared all too quickly, with the last software being released in early 1996.

The real nail in the coffin for LaserDisc games was, of course, the advent of real-time 3D video games in the '90s. Powerful consoles like the Sony PlayStation, Sega Saturn and Nintendo 64 were capable of producing three-dimensional graphics with which the player could fully interact, making the shallow nature of LaserDisc titles seem pathetically limited in comparison.

That wasn’t quite it for LaserDiscs, however. The discs were manufactured right up until 2009, and they were relatively popular in Japan, where it was estimated that 10% of households owned a LaserDisc player in 1999. But the launch of DVDs in 1996 was the death knell for the LaserDisc format. DVDs were smaller, cheaper, provided over twice the amount of storage and offered much better picture quality when compared with LaserDiscs.

The era of the giant shiny disc came to a swift close, but what a wonderfully bizarre selection of video games it left behind.