We’d be willing to bet that if you quizzed any games developer, they’d admit that pushing a system to its absolute limit is one of the most satisfying parts of the job. Taking a piece of hardware and making it do things it really shouldn't be capable of shows incredible talent and skill, and no doubt comes with a massive helping of pride on the part of the individual — or studio — responsible.

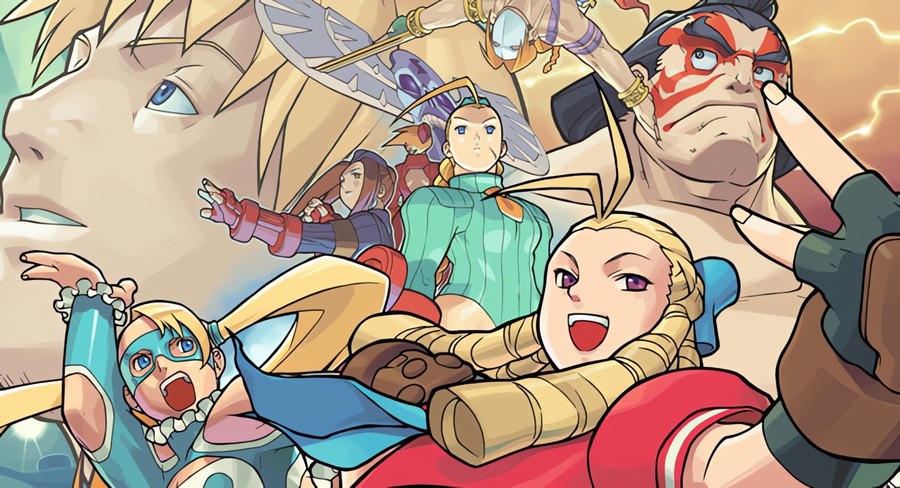

The history of gaming has seen many titles which have successfully wrung every last drop of performance from their host platform: Gunstar Heroes on the Mega Drive, Star Fox on the SNES, Donkey Kong Land on the monochrome Game Boy, to name but three examples. Another is Street Fighter Alpha 3 (or Street Fighter Alpha 3: Upper, depending on how pedantic you wish to be about the title) on the Game Boy Advance; a remarkable technical achievement by a small, UK-based developer by the name of Crawfish Interactive. Crawfish is sadly no longer with us, and ironically the blame can partially be laid at the feet of the studio’s crowning glory.

"We did a great job which obviously went down well with Capcom"

Crawfish Interactive was founded in 1997 by Australian programmer Cameron Sheppard. Sheppard had previously worked for Aussie studio Beam Software (responsible for the legendary SNES RPG Shadowrun and now known as Krome Software) before moving to the UK to work with Probe on the Game Boy conversion of Mortal Kombat II. Allied closely with the now-defunct publisher Acclaim, Crawfish specialised in portable titles for the Game Boy and Game Boy Color systems. The company’s talent in this field allowed it to gain a considerable selection of clients, including Virgin Interactive, which at the time was the UK publisher for all of Capcom’s titles.

“We developed Street Fighter Alpha on the Game Boy Color for Virgin, who were handling the license for the handheld format,” remembers Sheppard today. “I think they approached us after seeing Crawfish in the press all the time. We did a great job, which obviously went down well with Capcom.”

At the time, Nintendo was close to releasing the Game Boy Color's successor, and Crawfish wanted to make as big a splash as possible on this new console. Given the positive relationship with Capcom, it made sense to focus on porting Street Fighter Alpha 3 — the company’s latest coin-op smash hit — to the new machine.

It was a bold proposal, but Crawfish’s success with Street Fighter Alpha on the Game Boy Color had given it an understandable boost of confidence. “We produced some mocked-up screenshots of what we thought we could achieve on the Game Boy Advance for Street Fighter Alpha 3, plus a few videos of a couple of characters fighting in front of a background,” explains Sheppard. “Capcom obviously liked what they saw and gave us the contract.”

Crawfish had previously been successful in carving out a solid reputation for creating playable licensed titles, but there was a feeling within the company’s Croydon offices that Street Fighter Alpha 3 could be the project which took the studio to the next level. “It’s a hugely successful game franchise and our conversion had a release date coinciding with the Game Boy Advance’s release date, which was right before Christmas 2001,” states Sheppard. “The royalty deal was very good, coupled with a decent exchange rate at the time. Seven figures at least seemed very likely — plus the prestige of being responsible for what would have been the Game Boy Advance’s star title for that Christmas.”

Crawfish didn't take the job lightly and threw considerable manpower behind the conversion. “The programmer of the Game Boy Color port of Street Fighter Alpha was the lead, and we also hired an additional programmer to solely write the run-time data compression which was crucial for quality graphics and sound,” recalls Sheppard. “We also had the same artists from the Game Boy Color version of Street Fighter Alpha working on it. The lead artist was very passionate about the franchise, and was also responsible for the mocked-up screenshots and videos we used to help land the deal.” Even so, Crawfish’s then Director of Development Mike Merren feels that more could have been done at the time. “We certainly put the best people for the job on the game," he says. "But in hindsight we didn't put enough people on what should have been our golden egg, and in the end we spread ourselves too thinly. We were signing a lot of projects and in the end things were missed regarding the way the product was slipping, and we didn't plug the gap.”

"It was an amazing technical feat by the coder to actually get everything into the cartridge"

Fitting an entire arcade game into a handheld system was quite an achievement, and required some technical tricks. “We hired an industry veteran programmer to devise and write the data compressor and de-compressor so we could squeeze as many frames of animation onto the cartridge as possible,” reveals Sheppard. “This also allowed space for fantastic backgrounds and loads of music and sound effects.” Merren is still amazed at the volume of data shoehorned into that tiny Game Boy Advance cartridge. “From what I recall we agreed to get everything in the game that was in the PlayStation version, but then on top of that Capcom wanted three additional characters — Eagle, Maki and Yun,” he says. “When we started there were estimates of how much room we would need on the cartridge and it was wildly wrong. It was an amazing technical feat by the coder to actually get everything into the cartridge — we just wouldn't have had a product without it.” As it stands, Street Fighter Alpha 3 on the Game Boy Advance wasn't quite a perfect port — it lacked some backgrounds and sounds — but it did include every fighter, as well as the additional three requested by Capcom.

Despite its demands, Capcom was quite happy to give Crawfish plenty of space during the vast majority of the development period, but it wasn't plain sailing by any means. “They were very hands-off, until we got to bug testing stage and then they provided us with extensive bug reports — which were in Japanese, so we then needed to get them translated,” says Merren. “It was a tough process at the end that extended things even further — we probably took three times longer from the Beta stage to completion than we did on any of the other projects we did. Looking back, I think we gave Capcom too much respect and didn't push back on areas of the development that we should have.”

Indeed, the challenge of porting a leading arcade fighter to a device small enough to fit in your pocket was perhaps underestimated; Street Fighter Alpha 3 missed its proposed launch date, giving the team at Crawfish a considerable headache. So what happened? “A combination of many things,” admits Merren. “Over-promising what was possible and then not trying to push back on the publisher, not recognising the slippage that was occurring early on, spreading ourselves thinly over many other projects, an over-extended Beta period due in part to language barrier and also down to the fact that what we were trying to achieve by fitting such a big game onto a small handheld led to a large period of bug fixing.”

Capcom’s reaction to the delay was predictably negative. Sheppard and Merren were hauled in front of Capcom’s top brass and were told that their fee would be cut and the promised royalties would be cancelled. “They were up in arms, to say the least, and rightly so,” admits Sheppard. “They entrusted us with their prestigious title — not only to develop the best version possible for the Game Boy Advance, but to be released in time for the Christmas 2001 sales. I was extremely frustrated, not only for the obvious reasons but also personally, as I had personal guarantees with the bank for Crawfish’s debts which began to grow for other reasons, especially during 2002. Losing the final payments from the advance — plus the royalties — was a deep blow at a bad time.”

The timing couldn't have been worse. "Crawfish was in a delicate position due to a lull in signing new titles which can happen after new hardware is announced," explains Sheppard. "In this case, it was the Game Boy Advance. Publishers can drop support for the existing hardware when new hardware is announced, and delay signing titles for the new hardware until they are sure that the new hardware could be successful." It got to the point where it became obvious to Sheppard that the company could only survive if it was acquired by a larger firm, and in November 2002, that goal was almost achieved — but sadly, the deal fell through at the last minute. Crawfish Interactive ceased trading the next day, bringing to a close one of the most underrated UK development studios of recent memory.

"At the time the company went under we had released around fifteen GBA titles and had another six in development, one of which was Grand Theft Auto"

What makes the whole sorry situation even more ironic is that when Street fighter Alpha 3 did eventually hit store shelves, it was hailed as a classic by press and gamers alike. How did it feel to see the positive reviews after such a tumultuous development period? “Bittersweet,” states Sheppard. “Since we had lost the final payments of the advance and all the royalties — and since I knew then that Crawfish was likely to go under — I couldn't care less how it was received, really. Sounds harsh, but it was an extremely bad time, and I obviously had loads on my mind. I had the ramifications of a collapsing company to deal with.” Merren is in agreement. “I don't think I looked at a review of the game when it came out,” he admits. “We knew how good it was, but by then there were a lot of other things to worry about.”

Although Crawfish’s demise can’t be blamed solely on the delay of Street Fighter Alpha 3, Sheppard maintains that had things gone according to plan, his company might still be operating today. “Put it this way,” he says. “If it was completed and released in time for Christmas – the Game Boy Advance's first with a limited number of other titles vying for the shopper’s cash — we would have reaped considerable royalties, solidifying Crawfish’s financials for the foreseeable future. We would also have received much attention and would have had tons more work offered to us by not just Capcom themselves, but other publishers as well. We could have even become the target for a buyout, which would have been nice. If we had pulled it off, it would have been fantastic for Crawfish and we would have been propelled onwards and upwards towards something brilliant. So Street Fighter Alpha 3 didn't take us down per se, but it failed to not only save us, but also make us huge in some way. I certainly don’t regret taking the job on. If I have any regrets, they would be to do with my decisions I made at the time, just over 12 years ago.”

Merren concurs with Sheppard's assessment. “It would have propelled us forward in a big way," he says, but is keen to point out that other elements were equally responsible. "At the time the company went under we had released around fifteen Game Boy Advance titles and had another six in development, one of which was Grand Theft Auto. But we also had other titles cancelled. Margins were very tight as publishers were squeezing budgets hard on Game Boy Advance titles, and a one month slip on some of the smaller ones meant the profit was gone. Working on so many titles at a time spread us thinly and slippage become inevitable. We were a small Croydon handheld developer punching well above its weight — with global publishers wanting us to work on their titles, it was hard to turn a title down. In many ways, we were a casualty of our own success.”

Cameron Sheppard now resides in his native Australia and currently works in the TV and movie industries.

Mike Merren is development director at Big Ant Studios, which is based in Melbourne, Australia and produces titles for a variety of platforms.