Waxing lyrical about the dramatic transition from cartridges to CDs might seem somewhat twee in this era of seamless digital downloads and cavernous terabyte hard drives, but back in the early '90s, the entire industry was caught up in the excitement and anticipation of the glorious, data-rich future that those shiny plastic discs promised.

Companies such as Sega, Nintendo, NEC, Apple and Fujitsu threw millions upon millions of dollars of R&D budget into CD-based gaming hardware, while PC developers embraced the expansive storage offered by the medium to create games with full motion video sequences, hours of spoken dialogue and high-quality audio. During this time of intense upheaval, development studios had to shift from creating relatively simplistic cartridge-based titles to games that could make use of over 600 MB of storage space. This meant having to master a whole new range of design disciplines, including video, CGI, CD-quality music and much more besides.

Ian Hetherington was a true visionary who was never happy to sit back on his laurels. He gave us the time to achieve perfection rather than hustle us to 'get it out the door'

One of the companies which adapted best – and consequently found itself at the forefront of this technical revolution – was Liverpool-based Psygnosis, famed for publishing titles like Shadow of the Beast, Lemmings and Barbarian on home computer formats. Co-founded by the charismatic Ian Hetherington, the company invested heavily in the latest graphical technology, including Amiga rendering package Sculpt 4D and a raft of expensive Silicon Graphics workstations. Its pre-existing focus on creating lavish, cutting-edge visuals put the company in the perfect position to exploit the massive storage space offered by CD-ROM.

"It was probably the most exciting and rewarding part of my programming career," says former Psygnosis staffer John Gibson, an industry veteran who has also worked as a principal programmer at Sony Computer Entertainment's Evolution Studios. "Ian Hetherington was a true visionary who was never happy to sit back on his laurels. He gave us the time to achieve perfection rather than hustle us to 'get it out the door'."

This very ethos resulted in the famous Planetside demo, which caused former Psygnosis employee Richard Browne's jaw to drop when he saw it in action at a trade show. "[Ian] showed me the pre-rendered movie demos running on a Fujitsu FM Towns personal computer and I was utterly blown away – it was light years ahead of what anyone else was doing in the industry at the time," says Browne, who has since worked at the likes of THQ, Microprose and Universal Interactive Studios. He joined the team as it found itself at the crest of a wave. "The studio itself was a fascinating mix of incredibly talented and driven people – true artists in their fields pushing boundaries. It was also a really great mix of young gung-ho lads and experienced professional leaders, all living a dream. There was a real feeling that we could do just about anything."

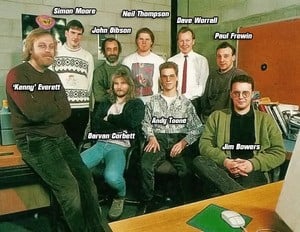

The foundation of a special R&D unit within Psygnosis – known as the Advanced Technology Group – helped the company to push the boundaries even further. "As an artist, it was incredibly exciting," recalls Neil Thompson, former director of art and animation at Bioware and now Art Director & Head of Audio at Inflexion Games. "I look back on it now and feel incredibly privileged to have been there at the birth almost of an entire medium. No one had done those cinematic intros before Psygnosis paved the way, and no one else was thinking in terms of what could be achieved with the enhanced storage and playback opportunities CD-ROM offered. Ian's great skill was to provide a bunch of very creative people with some extremely expensive hardware and software and basically let them run loose. Which is exactly what we did."

"Throughout the period of moving from the Amiga and into CD-ROM territory, it felt like no one really knew what was going to happen," adds Mike Clarke, who worked as a sound artist at Psygnosis during this period. "There was a definite paradigm shift going on in games, but where it was going to end up was very difficult to predict. After all, it was still very far from the mainstream at that point. What was clear was that we were involved in something very new indeed. There was always something new and cool happening in one of the rooms somewhere; some new technique being invented or some new hardware being tinkered with that no one had heard of before. Some of what the programmers were doing, nobody had done before. We were part of a golden period in gaming that defined what we know as the current game industry."

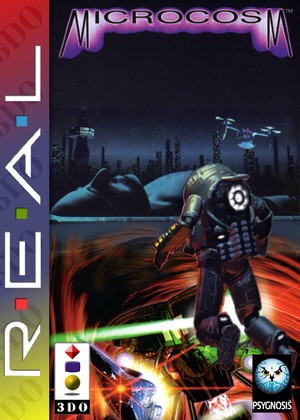

It would be the Advanced Technology Group that would create one of the most significant titles in the history of Psygnosis, but that game hasn't gone down as a classic it perhaps should have done. Microcosm, despite its innovative nature, is a relatively simple into-the-screen rail shooter which marries the gameplay seen in coin-ops like Sega's After Burner and Space Harrier with rendered FMV backgrounds and lush cinematic sequences.

Set in a futuristic world where corporations are the dominant power, the game places you in the shoes of a miniaturised pilot who is tasked with eradicating a mind-controlling robot virus that has been injected into the president of your company. Obvious parallels can be drawn between the game and Hollywood movies which boast the same basic plot. "As I remember, it was more Innerspace than Fantastic Voyage, as that was the effects film of the moment," recalls Thompson. "Very early, there was an idea of a counter-espionage plot theme, with no real specifics. Psygnosis had not long released Infestation and both Jim [Bowers] and I were keen on the claustrophobic nature of that early 3D gameplay, so I believe that influenced us as much as anything."

It's an indication of just how early Psygnosis was to the CD-ROM party that the lead platform for the game was the Fujitsu FM Towns, a Japan-only personal computer which was the only realistic candidate when development began. "At the time, it was the only platform out there that had a self-contained standardised CD drive," says Browne. "The PC market was an absolute mess, the Commodore CDTV and Philips CD-i were still in development and Sega's Mega CD wasn't even on the horizon. It was nice to have a target like that. I still remember to this day sitting late in the office with Phil Harrison ripping various cards from different PCs and installing every driver known to man to finally configure a PC that would run the 7th Guest." Having a stable and established hardware configuration was a big bonus.

I believe Fujitsu handed over oodles of cash! They eventually bought the FM Towns game engine that I'd written for what was, at the time, the princely sum of £250,000... Fujitsu were in the lead, needed content and had the money. Who wouldn't have taken the offer?

For Gibson, who served as the lead programmer on the game, the FM Towns was a potent platform, despite its relative weakness compared to the consoles that were just around the corner. "It was a pretty powerful machine for the time, thanks to its 32-bit 80386 processor," he says. Of course, that wasn't the only incentive for Psygnosis to support the system. "I believe Fujitsu handed over oodles of cash!" laughs Gibson. "They eventually bought the FM Towns game engine that I'd written for what was, at the time, the princely sum of £250,000."

The Japanese firm's overt interest in games might seem unusual, but at the time, Fujitsu was preparing to launch the FM Towns Marty, a console version of the FM Towns computer which would be in urgent need of killer software. Jim Bowers – who worked on conceptualising Microcosm's sci-fi visuals and now plies his trade in the film industry – sums up the deal between Psygnosis and Fujitsu a little more succinctly. "A lot of research had already been done in-house. Fujitsu were in the lead, needed content and had the money. Who wouldn't have taken the offer?"

After years of toiling to cram the maximum amount of content into floppy discs, cassettes and cartridges, the staff at Psygnosis suddenly had oceans of space to play with – but this brought its own issues. "The big difference was that you didn't have to load everything into the machine before you began; you could stream data in as the game was played," Gibson explains. "That presented a new headache: how to get the most out of the 300k per second available which meant – in other words – what could we pack it down to? For the FM Towns, that was made easier by the fact that the FMV frames were output using the machine's hardware sprites whose data structure lent itself to high degrees of compression. I remember spending weeks investigating and eventually settling upon a compression technique. Its one drawback was that it had to repeatedly recurse the data until it found the 'best fit'. The compression was done on the FM Towns itself, which could take upwards of four hours to compress just one frame. The problem for me and my data compressor was that the Silicon Graphics images were too good! The compressor wasn't very good at dealing with gradual colour transitions; it produced banding. I can remember imploring Jim and Neil to make their renders more cartoon-like, which simply produced a look of disdain. The problem ultimately was that the SGIs rendered in millions of colours whilst the FM Towns could only manage 16 colours per sprite."

Bowers elaborates on the tension that existed within the team. "There could be quite a lot of debate between artists and programmers about how to compromise," he says. "Sometimes it was reasonable and polite, and other times we'd end up throwing stuff at each other. It's just the nature of the restrictions of the medium, which still exists, although to nowhere near the same extent. In terms of Microcosm, it came down to the calibre of the programmers, and Ian had hired very high-calibre people for that reason. I'm not sure if they'd agree, but I found that it would often boil down to trying to convince the programmer the benefits of the higher quality – be it pre-rendered, sprites, even vectors – which they knew but couldn't immediately see a solution for. Sometimes that would boil down to sulking or begging or acting like a prima donna, but many times they said they'd sleep on it and, you know what, they'd often come back with a solution the next morning or later in the week. Those were really the satisfying occasions because what everyone was working so hard on was going to look better than if we'd just left it at that."

It was a whole new world and I was just making it all up as I went along. It was easier because I could now do anything, but it was harder because I could now do anything

Of course, imagery was just one part of the equation – CD also allowed for better music and sound effects. Audio artist Clarke found that he had to up his game considerably. "I went from a skill-set of making music sound good in Protracker on the Amiga to suddenly having to make music at full CD quality that had to compete with established artists," he says. "It was a steep learning curve, but certainly one that I welcomed. I didn't have a clue what I was doing, and it was great. I'd done some freelance music for Psygnosis before joining and was doing bits of audio on various games when I joined full-time, but when I was shovelled off to the other building to do the FMV audio for Microcosm – alongside Kevin Collier, a freelancer – my first question was 'What's FMV audio?' Although there had been short intros done for Amiga games for a long time, this was something else entirely. There were loads of movie-quality cut scenes, and for each one, I had to provide individual samples and a list of pitches and frame timings for when the programmer should trigger them. It was a whole new world and I was just making it all up as I went along. It was easier because I could now do anything, but it was harder because I could now do anything."

The rapid pace of technology meant that the extra storage offered by CD was quickly and ferociously consumed by all of the audio and visual content Psygnosis' artists were creating. "Creating that much data at first seems like a hard task," explains Browne. "But because creation tools were becoming widely available at the same time CD was coming online, it actually became a limitation in some respects – just as much as disk or cartridge. When the SGIs and Softimage arrived at the studio, the ability to produce movie-quality rendering – tens of thousands of frames – meant that gigabytes of data was put in our hands literally overnight." Bowers sums up the situation best. "Challenge: 'Bet you can't fill this up.' Response: 'I bet we can.' Guess what happened?" he says with a smile.

Content creation aside, Gibson faced problems when it came to programming thanks to certain rules laid down by Fujitsu, which was – after all – bankrolling the project. "Fujitsu insisted that I use the Towns OS rather than program 'down to the metal'," he recalls. "Their OS was unbelievably slow, so Ian had to persuade them to part with the machine's hardware docs or it was no go. He eventually succeeded, and as a result, the game engine and its associated tools were all written in 80386 assembly language."

Thankfully, the game's central premise – travelling down a narrow network of blood vessels – made Gibson's job a little easier. "I think one of the main attractions of the environment was it lent itself well to the time restrictions we had to put a game together," he says. "If it had been set in an open environment, for instance, then we'd have still been building the backgrounds months after the very strict deadline, which was so unmoveable that Fujitsu sent two of their guys to sit with us through the whole development."

I can remember Ian showing some Japanese 'dignitaries' around one day – not sure if they were Fujitsu or Sony – and he proudly demonstrated the auto-pause feature by opening the door on my FM Towns. Unfortunately, the game was running from a CD emulator on a hard disc at the time, and it rather embarrassingly just carried on when Ian opened the door

Gibson's coding talent allowed him to come up with some inventive tricks, but they didn't always go according to plan. "One of the Microcosm game engine's special features was that if you opened the CD-ROM door, the game would automatically pause and then pick up where it left off when the door was shut," he says. "I can remember Ian showing some Japanese 'dignitaries' around one day – not sure if they were Fujitsu or Sony – and he proudly demonstrated the auto-pause feature by opening the door on my FM Towns. Unfortunately, the game was running from a CD emulator on a hard disc at the time, and it rather embarrassingly just carried on when Ian opened the door."

Despite these unintentional – and often amusing – moments, Gibson's innate coding skill helped other members of the team considerably and enriched the entire package. "From a design perspective, there was a whole timing issue in terms of how quickly you could make transitions from a block of pre-rendered animation to the next," Browne explains. "John did some pretty amazing work to make it feel like you had as much control as possible over guiding the ship between the options down the veins, and I think Andy Toone did a lot of work on the lung level to make it feel much more free-roaming. To be honest, the highlights of the game for me were the end-of-level bosses that Nick Burcombe [who would later serve as the lead designer on WipEout] came in and designed with Jim; they really felt like classic shoot 'em up bosses."

On the audio side of things, Clarke's biggest headache was sourcing suitable sound effects to accompany the visuals and gameplay. "The biggest question was where on earth could I get samples from?" he remembers. "There weren't thousands of sound effect libraries available back then. I didn't know it at the time, but there were actually a couple available – however, even if I'd known of their existence, we couldn't have afforded them because they cost tens of thousands. All of the sound effects had to be synthesised from scratch, taken from other Amiga games and messed with, or sampled from films. The legality of using sounds from other sources wasn't really known or considered, and there was no other option anyway."

On the theme of audio, the FM Towns version of Microcosm was also notable for employing famous musician and former Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman to compose several tracks for inclusion in the game, which he recorded in just over a week. A grand total of 12 minutes of studio-quality material was forthcoming, although there were caveats to consider here, too.

"Wakeman's music was only licensed for the FM Towns version and couldn't be played during gameplay because you couldn't play CD audio while the graphics were streaming; audio compression as we know it today hadn't yet been invented," Clarke explains. "For subsequent versions, Tim Wright [in-house Psygnosis composer better known by his recording name CoLD SToRAGE] had to do new music in Protracker so that we could have music in-game." Despite his star status, Wakeman's influence over Microcosm was therefore slight at best. "My only recollection of Rick Wakeman was having to keep his son occupied one Saturday when he came to a meeting at the studio on Harrington Dock," grimaces Thompson. "In our early twenties, we weren't big Yes fans." It's safe to assume that the same cannot be said of Psygnosis' top brass, as the company's eye-catching 'owl' logo was designed by none other than Roger Dean. Dean illustrated many of the iconic Yes album covers and his work often adorned the boxes of some of Psygnosis' early efforts.

We were fortunate to have John Harris on the art team, who had worked on movies before coming to Psygnosis – he built props for Aliens – so a spare office was handed to him to make a workshop after a trip to B&Q

Psygnosis already had a reputation for lavish introductory sequences thanks to its Amiga output, but Microcosm would take this to the next level. The game's five-minute intro allowed the studio's artists to truly stretch their creative muscles and break new ground in the process. Bowers reveals that despite the polished nature of the final sequence, it was created on a shoestring budget. "There was very little money to spend, but I'd collected every issue of Cinefex to date, so there was an inkling of how to go about it," he says. "Not having any video capability, we hired camera and lighting equipment – with, I think, film four lights with fragile bulbs – from a Liverpool Arts-based video outfit and bought a roll of blue screen paper from B&Q which turned out to not be proper chroma blue. The chroma-keying software was written by a genius, Stewart Sargaison, which meant we could box-select some pixels on the footage, and it would create an alpha channel."

The team had some expert help on hand to assist with these sequences, thankfully. "We were fortunate to have John Harris on the art team, who had worked on movies before coming to Psygnosis – he built props for Aliens – so a spare office was handed to him to make a workshop after a trip to B&Q," continues Bowers. "John took a load of wood board, glue guns and techy paraphernalia, made the guns and other props and built-up an old tank helmet I had lying around. He'd emerge now and again covered in wood dust, looking like he'd be in a mining accident. An exercise treadmill meant people could walk or run on the spot during the filming, although running at two in the morning after a full day's work meant we sometimes had catchers lying offscreen in case someone dozed off. The footage then became textured cards in the 3D environment, hence very few shots show anyone in contact with the ground. Shooting took place once the sun went down, as we were filming in the office and it only had normal blinds on the windows. By the time we'd finished shooting, we were down to one light bulb and improvised reflectors because we couldn't get the money to buy new bulbs. Editing was done inside Softimage 3D's compositing package, which meant I had to cut it all linearly with no room for errors. Nuts."

As if to truly hammer home the low-cost nature of the production, all of the roles in the intro are played by Psygnosis employees. "I don't think the concept of using professional actors ever crossed our minds, to be honest," admits Browne. "We were using anything and everything that came to hand; there wasn't any time to think about casting actors – nobody at that time had ever really done stuff like that. For example, 3D Animator Paul Franklin plays a nice prominent part in the sequence. I'm surprised he didn't mention it in his Oscar acceptance speech for the FX on Inception." For those that aren't aware, Franklin now works in the movie effects business and did indeed get an award for his work on the Christopher Nolan's seminal movie. Bowers elaborates further. "We couldn't afford professional actors – and besides, we got to be immortalised and a future Oscar winner played one of the characters – though not for acting – so who needed them? It took a toll, though, and I think the lesson was learned, so professional actors played the parts for Krazy Ivan [a PlayStation 3D action title from 1996], along with it being shot in a professional studio. Trivia: Jason Statham auditioned for the lead on that one."

The audio side of the intro was also produced on a small budget. "I remember Jim bringing in two really cheap toy walkie-talkies as he wanted the radio speech to sound realistically low quality," recalls Clarke. "The sound effects themselves all had to fit into RAM because it wasn't possible to stream audio along with the video." Because the game was intended to launch on a Japanese machine, the team pushed for Japanese speech during the attract sequence – and had to call upon the only native speakers close to hand. "We pleaded and pleaded with the Fujitsu guys to do some voice dubbing for the intro," Bowers says. "They were assigned to literally sit with us, so we just wouldn't let them off the hook until they agreed."

As an FMV title running on a machine that had only a fraction of the power of a modern smartphone, I reckon it stands up pretty well. The thing is, FMV was never going to be the future of gaming because the games had to be pre-scripted rather than dynamic

Clarke worked his magic on the results. "There was a fair amount of Japanese speech, and I spent days getting it down to as little memory as possible. Not speaking Japanese, I obviously had no idea whether it was understandable or not, so before it went into the game, I accosted a Japanese guy from Fujitsu during a visit to our office and had him listen to the whole thing to make sure I hadn't cut off the ends of words or reduced the quality so much that it had just become noise. The English version didn't come until later, but wow, that was some terrible voice acting." Bowers isn't happy with the English dub, which would be used in subsequent ports of the game. "I still want to kill whoever dubbed that 'Peter Lorre' voice over me."

Microcosm would gain the distinction of being the cover star of the inaugural issue of EDGE magazine, and in turn, would become a poster child for the CD-ROM generation. However, the fact that the FM Towns never made it out of Japan limited the initial impact of the title in the West; ports appeared later on the Sega Mega CD, PC, Amiga CD32 and 3DO, but by then, similar titles had hit the market (7th Guest, another CD-ROM star, launched the month after Microcosm arrived in Japan and arguably overshadowed Psygnosis' game). The critical reaction was lukewarm, and today Microcosm is regarded by many as an illustration of the folly of combining video with interactive elements. "As an FMV title running on a machine that had only a fraction of the power of a modern smartphone, I reckon it stands up pretty well," counters Gibson. "The thing is, FMV was never going to be the future of gaming because the games had to be pre-scripted rather than dynamic."

"I think we understood the limitations of what could and couldn't be achieved, especially as the first of its ilk," adds Browne. "In effect, we were layering a fairly simple shooter over a beautiful background. As a game, I don't think Microcosm holds up well at all because the visuals which astounded everyone back then now look horribly dated – some of Nick's boss battles are still cool, mind." Clarke feels the game is actually much more accomplished than it is given credit for. "I really don't see what more could have been done to make a playable arcade game out of chunks of video. The gameplay is pretty simple, but holds up reasonably well. It's a whole lot better than a lot of the drivel that was around at the time." Bowers is more pragmatic. "It was what it was, and all it could have been at the time."

It was the FM Towns adventure that got Psygnosis into bed with Sony. I believe Sony was looking at a number of software development houses to buy into to support their new CD-based PlayStation, and it was undoubtedly its technology and talent that got Psygnosis the nod

Critical legacy aside, Microcosm was still a valuable project for Psygnosis and secured the studio considerable recognition from within – and outside of – the games industry. "Maybe the game itself wasn't a big seller, but I think Psygnosis did pretty well out of its technology," says Gibson. "The engine was used to produce a tailor-made version for Pfizer, an American drugs company, to use to promote their cholesterol-reducing drugs, and I doubt that came cheap! Most of all, though, it was the FM Towns adventure that got Psygnosis into bed with Sony. I believe Sony was looking at a number of software development houses to buy into to support their new CD-based PlayStation, and it was undoubtedly its technology and talent that got Psygnosis the nod."

The rest, as they say, is history. Psygnosis was purchased by Sony in 1993, and with titles such as WipEout, Destruction Derby, Colony Wars and Formula One would help endear the PlayStation to millions. It was rechristened SCE Studio Liverpool in 2001 and, a little over a decade later, was closed by Sony, bringing to an end a story that spanned three glorious decades.

While Microcosm may not go down as a solid gold classic, it arguably laid down the groundwork for a new era of games development and its impact is still keenly felt twenty years on. "It was an exciting, innovative time," says Clarke. "Back then, I was paid appallingly and had to work hours that no human ever should, but I'm thankful to have been there right at the beginning and been part of a team of such great people doing such amazing things."

Browne has equally positive memories. "My recollection of the development process was just sheer pride at working with an unbelievably talented group of people and achieving something that was not only pioneering for the time but done on a completely fixed timeline. The FM Towns Marty was launching in Japan whether our game was there or not; getting that game complete as a launch title was an outstanding achievement."

Thompson shares the same warm feelings towards his time spent at Psygnosis. "What really sticks with me is that it was a wonderful time in my life when there were no rules to game development and creativity, inspiration and risk-taking were given free rein. It was also a great, tight-knit group of people who worked and socialised together for what seems like an age – but was in all probability only a couple of years – and achieved amazing things."

This feature originally appeared on Eurogamer and is published in an updated form here with kind permission.