Our ability, as humans, to react to stimuli using our hands is an intrinsic component of video games, but equally as important has been our genetic ability to see things that aren't necessarily there. We call this act of misperception "pareidolia", and a valid question is: without pareidolia, would video games even exist?

"I saw a duck before, when I glanced at this. I thought, those are strange-looking ducks. I definitely saw a duck," says Professor Sophie Scott CBE, Director of the Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London, when shown images of the dragons in Adventure, during our lengthy discussion on pareidolia. Of course, she's not alone, many players interpreted them as ducks. Even the game's creator Warren Robinett agrees, saying in 1997: "What can I say - the dragons do look like ducks. It was just a different era of game design. One person wrote the code [and] created the graphics. I guess I was a better programmer than artist, but hey, I kind of like those duck-dragons."

Robinett's artistic ability, however, isn't the sole reason for the duck-dragons. Our cognitive tendency to interpret abstract imagery is genetically hardwired. Pr Scott is a leading expert on this fascinating aspect of the mind (and a keen connoisseur of golden-age video games), explaining: "Pareidolia is the tendency for humans to see things that aren't there. Things that are familiar in other structures. A classic example is seeing a face in the clouds, or a name in some seaweed that's washed up. When you experience pareidolia it's less about what's out there, and more about what you're expecting. Perception for humans, and all mammals probably, isn't just a veridical set of information about the world that goes to your brain, and your brain decodes everything and works out what's happening. Your brain is always forming predictions and guesses. So perception is a very active process." Pr Scott also elaborated on how pareidolia goes beyond the visual and can include auditory misperceptions too, which may explain why ghost-hunters swear they can hear spirits in scratchy audio recordings.

Type "misinterpreted sprites" into Google and you'll find people describing the alternative ways their brains guessed old videogames. There are many lengthy forum threads, including on NeoGAF and ResetEra, while Reddit has its own sub-forum dedicated to the phenomenon. There are hundreds of examples, of varying degrees of strangeness. For some these perceptions change over time. Mario crouching throughout the series is one example: in Super Mario World, some players saw the crouching sprite as a small bird, while NeoGAF user Polioliolio drew illustrations to show how his perceptions changed for Super Mario Bros. 3.

It's important to note that pareidolia isn't just faces, though that's the most common manifestation; it can be anything. "From when they are born, babies will pay attention to faces," explains Pr Scott. "And they will pay attention to really, really schematic faces, like just a circle with two dots in it. This suggests that part of our genetic inheritance is a predisposition to see faces, and be interested in faces. The only thing I suspect changes with age are experience-based aspects of pareidolia. For example, once you've learned to read, then you'll be more likely to see letters in things."

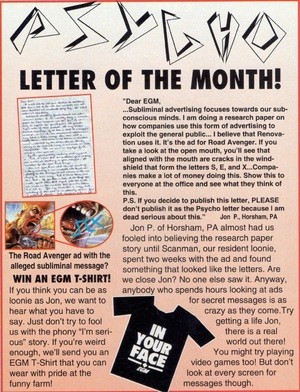

There are some great examples of this, for example in the May 1993 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly. Jon P. of Horsham won the Psycho Letter of the Month award (p16) claiming he could see the word "SEX" in the broken windshield of the Road Avenger Sega CD cover. The EGM crew mocked him, but if Jon P had squinted a little more, he would probably have seen the considerably naughtier "S***" and "F***" hidden in the cracks too. Because that's the thing with pareidolia – the mind can be manipulated if pushed hard enough.

So why will two people look at the same thing but see it so differently? "Because the original images from the old video games are low resolution," says Pr Scott. "They are low on fine visual detail. They are inherently ambiguous. But they're also quite complex – so there are different ways you could see it. And there could be something completely random about what's flipping you one way or the other. With two people something perhaps quite minor affects how they're processing what's out there, so they then channel an ambiguous figure into different routes. Potentially, as design improves, it becomes less ambiguous. But it's not guaranteed."

One component affecting how pareidolia manifests is past experiences. Pr Scott gives an excellent example with the Pixar film Cars, and how a vehicle's eyes are represented by its windshield. Which is a shift from the more common use of headlamps to represent eyes, as in Stunt Race FX.

"Every so often I had this weird experience when I was watching Cars with my son," recalls Pr Scott, "where the faces of the cars would flip for me, so the headlamps became the eyes. This is not unusual; that's a common way for cars to be represented as animate. And it was really disturbing! [laughs] And then they would flip back again. Pixar was insisting you saw it this way, by putting enormous eyes on the windscreens. Which worked. But every so often my brain was going: 'Well, let's just try that old way again.'"

Given this, it seems like different generations, each consuming different media, may manifest pareidolia unique to their generation's shared experiences. How would a generation growing up watching Cars process Stunt Race FX, would their minds occasionally swap styles?

We directed Pr Scott to a news story on how Nurse Joy in Pokémon looks like a disembodied head, commenting on the fact that previously the character looked as intended, but after seeing the alternative version my mind persists in wanting to see it in the new way. Pr Scott agreed, drawing a distinction between pareidolia and imagination. "I think one of the interesting things about pareidolia is it's very hard to unsee things," she says. "Once you've seen something as a face, it's hard to go back. So there's something fixed about pareidolia, in a way, that isn't necessarily true of imagination. I think imagination can include seeing something differently, but there's a sense in imagination of not just the world in front of you. You can imagine new things and create things."

When you think about it though, beyond the simple amusement of the above examples, our inherent pareidolia has actually defined what games get made, how these games are made, and even impacted how companies conduct business.

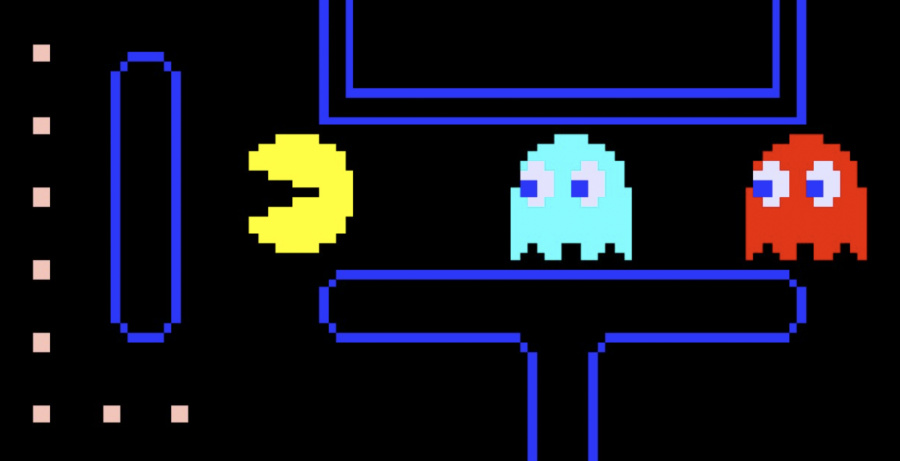

Possibly the most famous videogame example of pareidolia is Pac-Man – you've most likely seen the photo of its creator Toru Iwatani eating a slice of pizza, or being quoted: "If you take a pizza and remove one piece, it looks like a mouth. That's where my idea came from." This simple face, glimpsed in food, for a time defined the games industry. It had its own cartoon series and they even made vinyl records of the soundtrack. Namco grew large and powerful, and part of its foundation was that moment of pareidolia.

Beyond inspiring the creation of games, an understanding of pareidolia often dictated how they were made. In an interview with Retro Gamer magazine, ZX Spectrum artist Keith Warrington talked readers through his process of creating the recognisable characters in Skool Daze. His description in the Mr Wacker boxout is priceless: "There's one missing pixel on the characters' faces – the only way to avoid giving them huge noses. You can actually imagine an incredibly thin line there. Your brain makes it complete. Look at the headmaster: his cane doesn't really exist and his face is just a white cross."

We show Pr Scott all of these examples, asking for her opinion. "Those make a lot of sense," she replies. "You can think about any kind of visual art where people are doing something representational, as having a strong element of pareidolia. Because you want people to see. If someone draws a cartoon, like a Snoopy cartoon, our ability to see a dog or a child in those images is really being driven by our perception, our perceptual systems that want to see those things. To see faces in things that, actually, are just a couple of lines."

We suggest then, could the success of the cartoon and videogame industries be due to pareidolia? Could the ability of these industries to function hinge on this specific aspect of our brains? "Yes, I would say that, I think," confirms Pr Scott. "You've made me think about it that way, and I'm sure somebody else must have pointed this out before, but because we have this really strong tendency, given that we're doing this a lot, one of the skills in drawing cartoons and games is actually to find novel ways of exploiting that."

They See Things Differently In Japan

If personal experience shapes interpretation, how different could pareidolia be between cultures – if at all – and how would these differences impact development? Video games are an international product developed in each of the world's major countries, and exported between all of them. The question is pertinent when you consider that Japan dominated the global market from the early days, post-crash, to around 2006. It's a broad generalisation, with multiple affecting factors, but consider these statements: for four hardware generations Japan was #1 (NES to PS2); Japanese console games usually outshone Western console equivalents; Japanese arcade games defined the arcade sphere, from Space Invaders and Pac-Man to Donkey Kong, Gradius and Street Fighter II. All of this up until the Xbox 360 era when high-definition photo-realism started becoming the norm. (Japan arguably failed to get a foothold in the early Western computer market only due to very different bespoke operating systems.)

Certainly, Japanese developers believed that foreign audiences would have trouble accepting their in-game style, and altered games accordingly. One of the lead programmers at Chunsoft and director on Dragon Quest III, Manabu Yamana, gave a revealing account of how Enix viewed the American market when interviewed in The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 3.

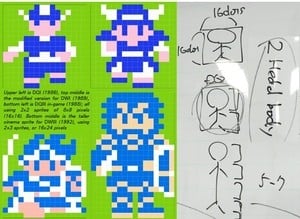

"At the time of Dragon Quest III there was concern the characters wouldn't be appealing to Western audiences," Yamana said. "So we changed the opening, showing more realistically-proportioned characters. He's pretty small, the regular Dragon Quest character, isn't he? He's actually described in Japanese as ni-tou-shin: the 'ni' means two, the 'tou' is the head, and 'shin' is the body. The head-body balance in Japan is 1-to-1, so a body made of two heads. To appeal to the American public, there's the problem of the character's size, the balance of the head-to-body ratio. The translation team mentioned this would be difficult to accept for the American market – they wanted us to modify and make it more appealing. So we switched to a proportion where the head is between 1/5 to 1/7 of the character's height."

This explains Enix's localisation policies, and we could debate how accurate their beliefs were. But delving a little further, Yamana hits upon a primary reason for Japan's success – its ability to work within limitations. As he explains, "Dragon Quest was on Famicom, and the hardware was not great – certainly not compared to what we have now. Your character sprites are 16 pixels by 16 pixels, so this ni-tou-shin style of character is really the only way to do it. Even for the US market, it's only in the opening cinema that you have these more realistic proportions. In the game itself, all the characters are based on this ni-tou-shin proportion." By creating these small oddly proportioned characters, Japan was able to make use of pareidolia to keep within the restraints of the hardware.

The possible cultural effects on pareidolia took up a lengthy part of our discussion with Pr Scott, and she confirmed there are examples, mostly to do with writing systems. Nike for example, in both 1997 and 2019, landed in hot water with designs for its shoes which, to the Arabic reading world, resembled the word for Allah.

As Pr Scott revealed though, "Now, no one saw that in the West, because they were not readers of an Arabic script. You'd have to have grown up reading the language to be affected. So there's that kind of constraint, and there are other cultural differences in how information is used. It would be entirely possible if Japanese people are very familiar with representations of humans with proportions you describe, in cartoons or in different low-resolution formats, they might be more fluent in perceiving that, than someone from the West. Although I don't think it's impossible for people in the West to cope with, because we do have quite a lot of funny-looking different representations of humans in cartoons, don't we?"

We agree, pointing out that today Western audiences clamour for that distinct Japanese style. I also raise the topic of how Japan's Kanji writing system, adopted from China, is very pictorial. The Kanji for fire actually looks like a small fire. To which Pr Scott adds, "I think you do see the world differently if you read an alphabetic script like we do, than if you read a script like Kanji. You have characters that contain symbolic information. Learning to read means learning new Kanji. So you could make a plausible argument that said you might have differences between the visual processing for different kinds of reading systems, which do have big influences on how we parse visual information. You could imagine that would have an effect. Not just in the sense of, 'Do I read this language or not?'"

Pareidolia Worth $250 Million

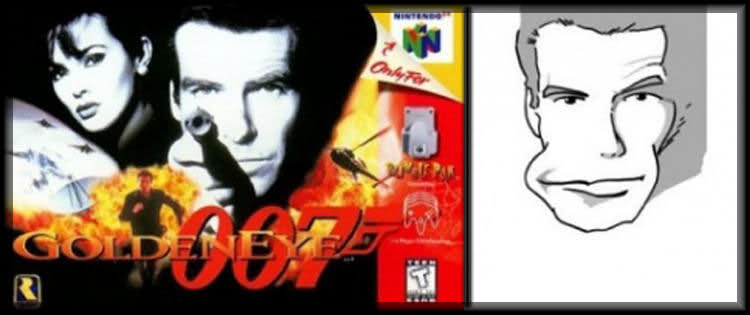

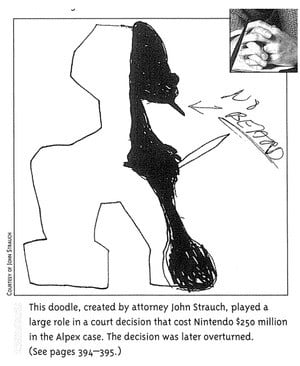

With all this discussion of how the "seeing" of recognisable figures is facilitated by pareidolia, one has to read with intense amusement the case of Alpex Computer Corporation v. Nintendo of America. On page 394 of Steven Kent's book, The Ultimate History of Video Games, he gives a retelling of events: "The case turned into a debate about whether 'on-the-fly' graphics differed from the technology in the Alpex patent. Nintendo maintained that while Alpex's bit-mapping was fast enough for games with 'linear player images', it lacked the speed for games with 'animated cartoon characters'. The highlight of the case was when John Strauch, lead attorney on the Alpex team, cross-examined Nintendo expert witness Stephen Ward, to corner Ward into explaining the precise differences between the two."

It culminated with Strauch saying to Ward: "Okay, so now I know how you are drawing the line. If we have a nose, two little arms, a tail, more hip, and the configuration I have drawn, except for the beard, you don't know whether it is a linear image player or not; but if we add the beard, it is not." Members of the jury are described as attempting to hide their laughter during the ridiculous exchange, and this semantics debate over pareidolia cost Nintendo $250 million (the decision was later overturned). Ultimately, "linear player images" and "animated cartoon characters" are both just examples of pareidolia.

During our conversation, Pr Scott shared an anecdote which expands the connection between pareidolia and video games. Specifically how prolonged exposure to games can change how we perceive reality around us. "I had a version of Bejewelled," she begins, "and I can remember being at my gym and looking at the carpet, and I realised I was interpreting the carpet as a particularly good Bejewelled environment! [laughs] So I was classifying the carpet as I would when you're looking at what you're going to move next in Bejewelled."

We ask if this is like the Tetris Effect? The phenomenon where playing Tetris (or any game) for long periods results in similar game imagery bleeding into our thoughts, mental images, and dreams. "Yes, exactly!" confirms Pr Scott. "And you notice it as soon as it's happening to you. 'Oh look, hang on, that would be a great thing in Tetris.' I had it a lot with the computer game Myst. I quite often will get in environments and go: 'This is like an area in Myst!' [laughs]" Although beyond the scope of this article, it makes for an engrossing follow-up investigation. If our minds impose an anticipated reality onto an abstract game, to what extent can games augment our perception of reality?

Given that Time Extension covers the history of games, we had to ask if pareidolia makes older games better? If each of us processes the experience of older games by imbuing them with a personalised interpretation, even if it's extremely slight, would that not make them more satisfying? Does the cognitive mechanism behind having pareidolia parse Snoopy or any 2D character, generate a pleasurable qualia that photorealistic graphics lack?

"I think there's an element of that," agrees Pr Scott, citing her own experiences with games over the years. "The more realistic it gets, the more possible it is for the whole thing to collapse into the uncanny valley, isn't it? And that does happen when you have human representation. Thinking back to my own experience, I really loved playing the first version of Lemmings. You saw a great deal that wasn't really there – like the builders are building. As soon as versions of Lemmings looked a little bit more realistic I liked it less. It wasn't just because it was different, there was something kind of 'right' about that resolution. There's a strong element of personal investment. So it's rewarding when you see those things." For those curious, Pr Scott listed her five favourite games as: Myst, Lemmings, Catacomb Abyss, the original 2D Duke Nukem, and Gods by the Bitmap Brothers.

Based on scientific understanding of how human perception functions, everything in our lives is augmented by pareidolia. The more abstract or vague a stimulus, the greater chance of our minds using guesswork or prediction to interpret it. Whether it's a garbled song lyric, a Jackson Pollock painting, a pocket-dialled phone message, or our favourite classic video games. In the last of these examples, pareidolia has been especially important, since it has guided the evolution of what can be done with pixels in tandem with the evolution of the technology that displays them.

Pr Scott sums it up nicely. "The early games industry, like any kind of fairly crude visual representation, along with information, images, characters, faces, is relying on pareidolia to be successful, because if we couldn't do that, we would be going, 'That doesn't look like anything, that's just a strange collection of yellow blobs.' So even if they don't know they are doing it, they are relying on our ability to be able to interpret it. And of course, the person creating it on the computer will also do this. They are going to be experiencing this as well. So it's guiding how they do it. Games are thriving because they're able, even with very basic things, to trigger that pareidolia, and then people get that enjoyment."

To play the earliest video games is to experience pareidolia in its most intense form; early games are pareidolia made interactive. It seems fitting then to coin a term that describes this unique symbiosis. A pixel is the smallest block that makes up a videogame image; esthesia means the capacity for sensation and feeling; 'pixelthesia' therefore aptly describes that special magic that happens when our brains experience pareidolia during old games, and allow us to see beyond the pixel.

Comments 8

-Article: the dragons do look like ducks

-Some random corner of the internet circa 2001: SOMEBODY GET THIS FREAKIN’ DUCK AWAY FROM ME!

Thanks for this article. I think the reason games used to seem more "magical" in some ways was due to this "pareidolia". The original Legend of Zelda and the first few Final Fantasy games were a magical experience because your imagination did have to do a lot of the work. I still have a wonderful time playing modern games - but hyper realistic games - as amazing as they are, do take away some of the mystery of the game world.

Side note, I am a huge retro game player, and this site is very welcome!

I never really thought of it that way, but I guess it makes sense.

One thing I'm surprised wasn't mentioned was Game Freak's awareness of this in the early Pokémon games, with the main character "shrinking" after the introduction.

This is SUCH a good article, and this new site is KILLER. Your team is doing a bang-up job, I'm very thankful for your work!

NINJA APPROVED

Really interesting read, thank you. Really enjoying this new site so far.

I notice this phenomenon when I’m exercising and doing planks. When you you’re staring at the carpet really close up, the different shades of fibres and speckles make it really easy to see faces in the pattern!

Excellent article. There's nothing else like this out there. Keep up the good work!

This article may be the magnum opus of Hookshot Media articles. Fantastic read! Thank you so much for writing it.

Great, great read, thank you so much: having delved in game studies for a while, implementing the "mind games" aspect was extremely interesting!

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...