As one of Nintendo's earliest hits, Donkey Kong has a special place not only in the company's illustrious history, but in the realm of gaming in general. Despite its advanced years, the game continues to capture the imagination of players and, in more recent years, has been thrust back into the spotlight thanks to its seemingly evergreen appeal to high-score chasers.

However, what many people aren't aware of is that Donkey Kong wasn't actually developed by Nintendo at all, and the game itself was at the centre of a legal tussle which threatened to unsettle the burgeoning empire Nintendo presided over during the vast majority of the '80s.

The name Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. isn't one that most gamers are likely to be familiar with, despite the fact that the company has been trading since the 1940s. Initially established to manufacture transformers, choke coils and power supply components, in the '50s, it shifted focus to the production of broadcasting equipment.

Logging onto the company's official site today, you'll notice that it also creates items for the medical industry. There is no mention of an association with video games, which is surprising when you consider that Ikegami is apparently responsible for some of Nintendo and Sega's most notable late '70s and early '80s coin-op releases.

Finding solid information online regarding Ikegami is tricky, with the most fleshed-out source being the indispensable Game Developer Research Institute. According to this page, Ikegami was approached by Nintendo's Tokuzo Komai to develop and manufacture arcade games exclusively for Nintendo. The initial contract initially stipulated that eight titles would be made, all of which would be sold as Nintendo's own products.

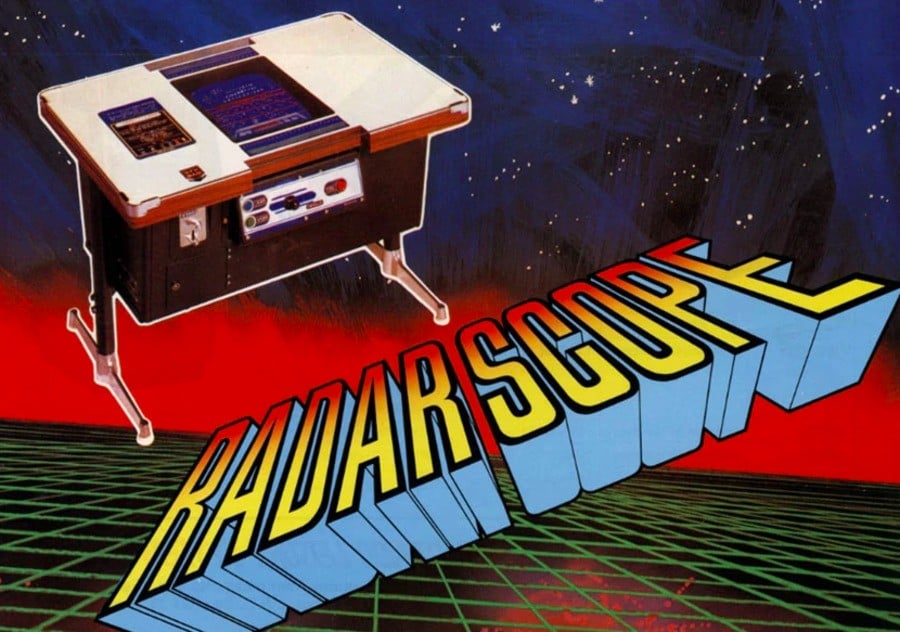

While it has not been conclusively proven, it is believed that these titles include Monkey Magic, Popeye, Sheriff, Space Fever, Space Firebird, Space Demon, Heli Fire, Sky Skipper and Space Launcher – presumably, the deal was extended to incorporate more than the original eight games, but finding solid conformation of Ikegami's involvement with these games is difficult. Of particular note is 1979's Radar Scope, which – despite the prominent Nintendo branding – was apparently designed and developed solely by Ikegami staff.

Of particular note is 1979's Radar Scope, which – despite the prominent Nintendo branding – was apparently designed and developed solely by Ikegami staff.

This part of the story will perhaps be familiar to Nintendo fans. Radar Scope was a success in Japan and, seeking to break into the North American market, Nintendo Of America president Minoru Arakawa placed an order for units in the US. By the time the units reached American shores, interest had waned, and Nintendo was left with a large amount of unsold inventory.

Arakawa asked Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi – his father-in-law – to provide him with a replacement game which could be quickly installed inside the unsold Radar Scope cabinets, thus solving the issue. The man chosen to design this game – which was seen as the last throw of the dice by many within Nintendo, it has been reported – was none other than Shigeru Miyamoto, a young and relatively inexperienced staffer at the time.

It's here that the commonly-reported history fails to mention the fact that Nintendo enlisted Ikegami's aid to develop Miyamoto's idea, which of course, became Donkey Kong. As the original developer of Radar Scope, Ikegami had the technology required to write the new game for the target hardware, and duly supplied all of the code, working to Miyamoto's game design specifications.

It is believed that it took four programmers and two 'pattern ROM' creators (credited as Komonora, Iinuma Minoru, Nishida Mitsuhiro, Murata Yasuhiro, Shigeru Kudo and Kenzo Sekiguchi respectively) around three months to create the game, based on Miyamoto's design. Ikegami's designers traditionally left a small calling card in each game they worked on; if you inspect the tile sets for Sega's Congo Bongo and Zaxxon (two other famous arcade titles the company appears to have developed) – as well as Donkey Kong – then it's possible to spot the Ikegami logo.

Also found buried in the code for Donkey Kong is the following message:

CONGRATULATION !IF YOU ANALYSE DIFFICULT THIS PROGRAM,WE WOULD TEACH YOU.*****TEL.TOKYO-JAPAN 044(244)2151 EXTENTION 304 SYSTEM DESIGN IKEGAMI CO. LIM.

According to the GDRI, between 8,000 and 20,000 printed circuit boards were made by Ikegami and sold to Nintendo, but it is believed that Nintendo copied an additional 80,000 boards without permission. No formal contract appears to have existed between the two companies for this job, so Ikegami retained the source code for Donkey Kong – it was never handed over to Nintendo, which would have serious ramifications soon afterwards.

Donkey Kong was a massive commercial success and effectively changed the fortunes of Nintendo forever; it was the firm's first genuine video game smash hit and became a global phenomenon comparable to Space Invaders and Pac-Man. A sequel was inevitable, but Nintendo didn't have the source code for the first game to base it on. In order to begin work on what would become 1982's Donkey Kong Junior, Nintendo employed subcontractor Iwasaki Giken to reverse-engineer the original version. If the Ikegami narrative is to be believed, this gives Donkey Kong Junior the distinction of being Nintendo's first 'in-house' video game, designed and developed entirely by the company itself without any outside assistance.

Speaking to the Japanese website 4Gamer.net in 2022 (and translated by Shmuplations.com), former Nintendo staffer Satoru Okada explains what happened:

"Donkey Kong Jr actually started as a way to get rid off the excess Donkey Kong PCB stock we had. 'Do something about all these!', President Yamauchi ordered us. Sometimes it seemed like that was the only kind of work that came my way. (laughs)

The problem was, we didn't have the source code for Donkey Kong. The programming for Donkey Kong was not created by Nintendo. If I recall, the development department rejected the plans they'd been given, and Ikegami Tsushinki ended up programming it.

So the Donkey Kong Jr. development began by reverse engineering the original programming. I didn't know anything about video game programming… I was like, 'uh, how are we supposed to make this?' So then we had three highly skilled programmers from Iwasaki Giken Kougyou come to our offices, and we spent our entire Golden Week confined to the office working on it.

I didn't know anything about the source code, so we just used the programming data as-is. The source code contained Ikegami Tsushinki's company name, the person who wrote the code, and a phone number. If we had converted the code to text we would have found that out, but we didn't. Because of that, the fact that we'd used the Donkey Kong source code was discovered, and it turned into a copyright infringement claim."

It's worth noting at this point that the copyright law surrounding programming wasn't clarified in Japan until 1985. Regardless, as Okada says, Ikegami was less than impressed with what it viewed as blatant copyright infringement; it felt that it owned the original Donkey Kong code, which had been disassembled to form the foundation of Donkey Kong Junior. It sued Nintendo in 1983 to the tune of ¥580,000,000 (around $4.3 million in modern USD). It wouldn't be until the turn of the next decade that this issue would be resolved; in 1990, a trial took place in Japan which determined that Ikegami was correct – Nintendo did not own the original code for Donkey Kong – a ruling which may well have had something to do with the fact that the two companies settled out of court in the same year for an undisclosed sum.

Without Ikegami, there would be no Donkey Kong, and without Donkey Kong, Nintendo – and video games in general – would have been very different today

Video game journalist, historian and Time Extension contributor John Szczepaniak – author of the indispensable Untold History of Japanese Game Developers – has revealed to us that he has spoken to an Ikegami USA employee who believes that none of the staffers involved with game development remain with the company, and, as we've already established, it would seem that Ikegami is perfectly content to airbrush its gaming achievements from history. Perhaps this was a condition of the out-of-court settlement with Nintendo in 1990, or maybe the firm simply views its work in '70s and '80s just like any other subcontracting job, and instead chooses to focus on its in-house achievements in the realm of broadcasting and imaging.

Whatever the truth is behind this mysterious Japanese firm – and we dare say the full story isn't out there yet – it's remarkable to think that it's partly responsible for Nintendo's meteoric rise at the time and, by association, can take a small amount of credit for the company's enduring fame and fortune, even to this very day. Without Ikegami, there would be no Donkey Kong, and without Donkey Kong, Nintendo – and video games in general – would have been very different today.

Thanks to John Szczepaniak and Kurt Kalata for their valuable assistance with this feature.