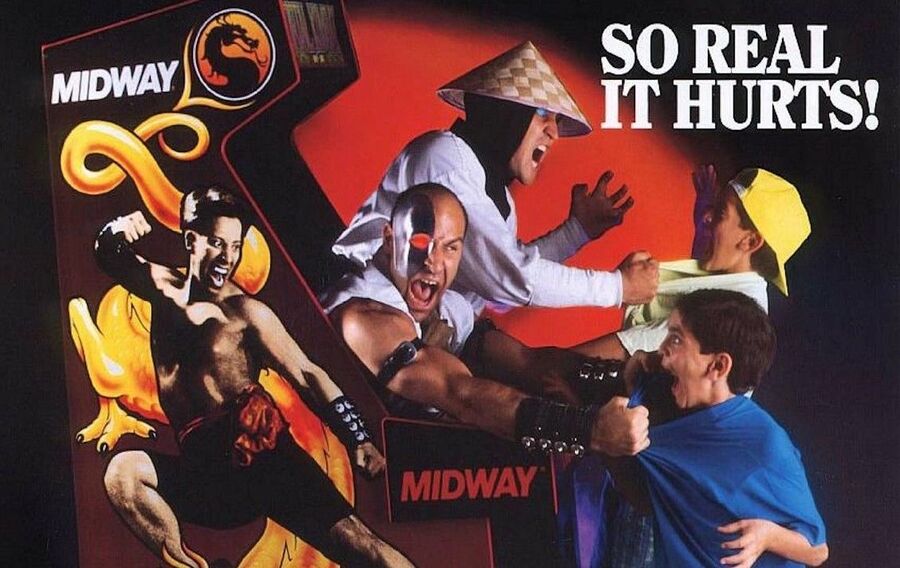

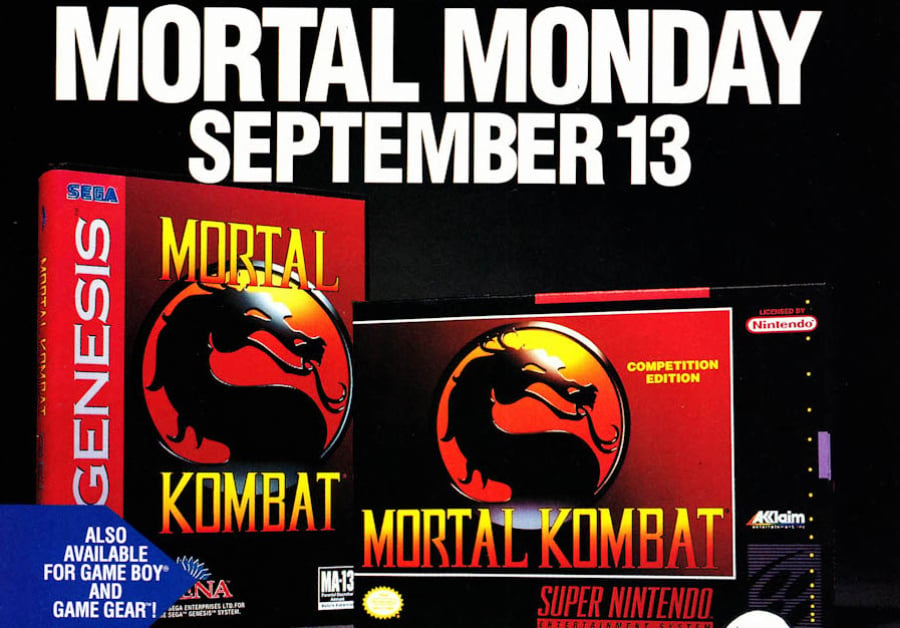

September 13th, 1993 was a significant day in the world of video games; seasoned players might remember it better as 'Mortal Monday' – the day on which Acclaim released the home conversions of Midway's Mortal Kombat arcade game. Following hot on the heels of Capcom's Street Fighter II and famous for its brutal 'Fatalities', digitised visuals and bucketloads of gore, this one-on-one fighter went on to spawn a franchise which continues to this day. While the series was born in the arcades, it's hard to imagine it would have been as successful were it not for the domestic ports which introduced it to millions of players the world over – and at the centre of that initial release was a battle that would present yet another thrilling chapter in the titanic 16-bit struggle between Sega and Nintendo.

Remember that Mortal Kombat was not necessarily thought of as a particularly hot property back then. It had just gone big in the arcades, but home gamers were less likely to have heard of it

Mortal Kombat was ultimately converted to a wide range of systems, including the original monochrome Game Boy and the Commodore Amiga, but it would be the Genesis / Mega Drive and Super Nintendo versions which would garner the most attention, as those two systems were the world's best-selling games formats at the time. Publisher Acclaim was the company which secured the home console rights to the game, and it set about distributing conversion duties to the studios it trusted best. For the Sega version, that was UK-based Probe Software, which had previously worked with Acclaim on titles such as Alien 3 and Terminator 2: The Arcade Game, as well as numerous original games and home computer conversions of coin-ops for other publishers.

"Probe was very close with Acclaim at the time and I guess the successful completion of T2: The Arcade Game – as well as some other Acclaim Mega Drive projects they were handling at the time – meant that Probe was first in line," says Paul Carruthers, who was employed as a freelance contractor at the studio at the time. Carruthers had just worked on T2: The Arcade Game, and after that was completed, was offered the lead programmer role on the Sega version of Mortal Kombat. He took it on as just another job at the time. "Remember that Mortal Kombat was not necessarily thought of as a particularly hot property back then," he adds. "It had just gone big in the arcades, but home gamers were less likely to have heard of it."

For the SNES version, Acclaim selected Sculptured Software, a studio situated over four thousand miles away from Probe in Salt Lake City, Utah. Project Director Jeff Peters admits that like Carruthers, he perhaps wasn't fully aware of what he was dealing with when he first laid eyes on the game – although that stance changed rapidly. "When Acclaim picked up the license, they weren’t quite sure if Mortal Kombat was actually a good game or not," he explains. "It had just been released when we started discussing it and hadn’t yet established itself as a success with legs in the arcades. At the time, I was a highly competitive Street Fighter II player, so my initial frame of reference came from comparing Street Fighter II – and all of the mostly bad fighting game knockoffs at the time – to Mortal Kombat. It had a completely different look as well as a new fighting model that players were adopting as an alternative to Street Fighter II. Initially, I wasn’t a fan, but the more I played it in the arcades, I began to feel what was unique about the fighting mechanics and gradually began spending more time competing on Mortal Kombat than Street Fighter II."

We really understood the SNES hardware and how to get the most out of it. Later on, we definitely became known as the masters of 'Mode 7' and games that utilized that features of the SNES

Like Probe, Sculptured Software had a healthy relationship with Acclaim, and had already made quite a name for itself in the games industry. "We also had a great relationship with Nintendo on a first-party basis," Peters adds. "Sculptured had worked with them directly on NCAA Basketball, which showed how we really understood the SNES hardware and how to get the most out of it. Later on, we definitely became known as the masters of 'Mode 7' and games that utilized that features of the SNES." Even so, Sculptured Software had to pitch for the work. Thankfully, the studio secured the deal. "We made a passionate pitch of how we would develop the product," Peters continues. "After we made our pitch to Acclaim, they decided to send the Genesis version to Probe in the UK, who were considered the best Genesis developer at the time, and the SNES to Sculptured Software. Acclaim wasn’t quite sure of the strategy initially, but as it started to be clear that it was an arcade success that had legs, the strategy set in rather quick."

Indeed, as Mortal Kombat's popularity in amusement centres all over the globe became abundantly clear – helped in no small way by its bloody special moves which had sensitive parents covering their eyes in disgust – the project gained additional impetus. Acclaim was, at the time, famed for its arcade ports and licenced games, and relied on projects like Mortal Kombat to generate a healthy stream of revenue. Midway's gory fighter quickly evolved into one of the most requested games of 1993, and that added pressure on the two studios working thousands of miles apart.

In Utah, Peters and his team collaborated with the creators of Mortal Kombat to ensure it was as authentic as possible in terms of presentation and feel. "We worked very closely with the Arcade team at Midway – John Tobias and Ed Boon specifically," he says. "They also wanted the best version of the game for home sales, so we were aligned on that front. For the most part, the relationship was really great between the Sculptured and Midway teams, with the only real issues being development time and some unhappiness about the limitations of the SNES hardware specs, such as processor speed, palette limitations and audio buffers. But we worked through all that pretty well together. We had to cram a lot of stuff – art and code – into a very small, low-powered box."

Our first tactic was to do something no one else had done previously, which was to convert the actual arcade game assembly code to SNES, taking into account the things the console could and could not do

Peters and his team were actually breaking new ground with this particular conversion. "Our first tactic was to do something no one else had done previously, which was to convert the actual arcade game assembly code to SNES, taking into account the things the console could and could not do. We ended up perfecting this process starting with Mortal Kombat II – which we later ported – but we had made great inroads converting part of the game for Mortal Kombat and then recreating the rest by hand, based on frame-by-frame analysis of the arcade game; we just ran out of time with launch looming. Even so, thanks to all of our other projects we had lots of tools focused on art, palettes and compression. These tools helped to give us a leg-up in the visual sense of being able to maximize the cart size and push the visual fidelity of the product at the same time."

In terms of audio, Sculptured Software also pushed the boundaries of what was possible on Nintendo's 16-bit system. "Speech was such a big part of the arcade game, we wanted to keep as much as possible and set a new bar for audio," Peters explains. "With the limited sound RAM, one of our engineers came up with a process of ‘blasting’ sounds directly from the cart – without pre-loading them in RAM first – so that we could store more voice samples and pull more of the voice samples in real-time into the experience. If you compare the audio on both SNES and Genesis, there’s no comparison which is better in that area."

The technical gulf between the Sega and Nintendo versions of Mortal Kombat may be clear in terms of graphics and sound, but the SNES version lacked the one thing that arguably made the coin-op original so compelling for players: gore. "Nintendo was adamant about the 'no violence' or 'Family friendly' part early on," explains Peters. "So we knew as part of the SNES version, we had to design the worst of the violence away. We would submit new storyboards of 'Fatalities' designs to the team at Midway – Ed Boon, John Tobias and Ken Fednesna – of those we thought still retained the intent of the Fatality as well as sequences we thought Nintendo would approve. We went back and forth on a lot of designs while at the same time negotiating with Nintendo which Fatalities could stay 'as is'. Going from memory, I think we really only had to change two of the Fatalities completely; the rest we toned down with Nintendo’s oversight. We also took out all the blood from punches and kicks and instead changed it to 'sweat', which was mostly a palette swap on our part."

I think we really only had to change two of the Fatalities completely; the rest we toned down with Nintendo’s oversight. We also took out all the blood from punches and kicks and instead changed it to 'sweat'

Over in Croydon, Probe's experience was somewhat different. "From my perspective, Sega wasn't very involved, at least not until the latter stages," admits Carruthers. "To be honest, the development team was largely insulated from publishers and platform owners to keep our focus on the job." The Sega version didn't escape entirely unscathed, however; while it shipped with all of the gore and violent finishing moves intact, they were locked away behind a special code which players would have to input – a code which, upon release, was distributed by practically every specialist magazine on the planet. Carruthers explains that the decision to lock off this content came very late in development. "I put the gore on a switch so that it was easy to turn on or off as required," he says. "The version we did for the German market had gore switched off. The code that I originally put in was 'DULLARD'. I was quite proud of this, but the publishers thought it was too complicated to keep putting in – and probably too silly. Very near the end of the project, they asked us to come up with a code that used only the A, B and C buttons. My code was expecting seven letters – so there wasn’t an awful lot of choice." The eventual code was ABACABB, which is one letter off being the title of Genesis' (the progressive rock band, not the console) 1981 album.

Showers of blood and gore do not an accurate port make, however, and when it came to ensuring the Sega edition was faithful to the original, Carruthers used the best reference possible. "I was working from their original source code, so mostly it was self-explanatory," he explains. "There were a couple of questions I needed to ask Ed Boon and he was very helpful. I had a coin-op in my house to refer to, but I had a big problem trying to access the secret fight with Reptile, the green ninja. To be honest, I was never very good at the game! The team at Midway kindly made a cheat version of the coin-op ROM and sent it over to me so that I could see how the reptile fight worked." While Probe and Sculptured Software were separated by the Atlantic Ocean, they did help one another wherever possible. "We had a few calls with Probe during development; we had a good relationship with each other," Peters remembers. "We discussed each strategy in approach to porting the game, as well as any issues that came up and possible solutions. So although we were solving slightly different problems – gore vs. no gore, differences in SKUs – it was still valuable to share notes from time to time."

Following in the footsteps of Sega's famous 'Sonic 2s day' launch in November 1992, where Sonic the Hedgehog 2 was released globally on the exact same day, Acclaim decided to schedule its own marketing stunt with the aforementioned Mortal Monday. Millions of dollars were spent promoting this date, with TV commercials, magazine spreads and advertising billboards making sure that every console-owning kid on the planet was aware of the precise day they could get their hands on the highly-anticipated home port of Mortal Kombat – the problem was, the game absolutely had to be ready on time to pull off this promotional event, and that put intense pressure on both teams.

When it was starting to become clear how big a deal it was going to be, I started receiving phone calls at Probe from mysterious American characters who wouldn’t say who they were but were very interested in how development was coming along

"Sleep became optional through most of development," says Peters. "As the production continued, the hype for the game increased and publishing dates were locked in, time became our worst enemy throughout the entire development. We pretty much lived at the office to take advantage of every available moment with the time remaining. Also, we had Acclaim representatives living with us as well – for better or worse – trying to protect their investment. Although they couldn’t do much to help production, producers and others would literally fly out to Salt Lake to 'live' with us – clearly reporting back to the mothership in NY status at every moment – in an effort to 'help' production. The reality was that their crew couldn’t keep up with our round-the-clock development and started sending out multiple people in shifts to hover and 'help'. We had a great relationship with Acclaim and their producers, but I think this helps to illustrate the immense pressure that was building for the release; there was no concept of missing a date once all the marketing stuff got locked in."

Such was the level of expectation surrounding this release that Carruthers found himself getting a rather odd phone call towards the end of the project. "When it was starting to become clear how big a deal it was going to be, I started receiving phone calls at Probe from mysterious American characters who wouldn’t say who they were but were very interested in how development was coming along. These people turned out to be Wall Street stockbrokers who were trying to work out how likely the game was to be late, as this would have a big effect on Acclaim’s share value. It was very scary to think that Acclaim’s very survival was in question if I didn’t pull my finger out and get on with it."

The need to hit this date was a good motivator, but it came with a cost; while you could argue that no game is ever truly 'finished', Peters feels that he and his team could have made the end product even better had the time been available. "All development had to align around that release strategy. The unfortunate part is that it didn’t give any of us the time we needed to develop the product the way we wanted." Even so, when September 13th finally arrived, the commercial reaction was immense. "For the first time, my friends and family actually understood what it was I did for a living," says Carruthers with a smile. "I remember going to see Jurassic Park at the cinema with a big group of friends. Before the film started, there was an advert for Mortal Kombat – possibly one of the first examples of a home video game being advertised like that. My friends just stared at me."

For the first time, my friends and family actually understood what it was I did for a living. I remember going to see Jurassic Park at the cinema with a big group of friends. Before the film started, there was an advert for Mortal Kombat. My friends just stared at me

It was a game-changer for Peters, too. "Sculptured Software was already considered one of the top developers in the world, so this only cemented us. Mortal Monday was the most successful video game launch of all time up to that point, making over $50 million in its launch day alone. The anticipation was so high for the games that Acclaim literally bought the entire production of ROMs and other chips to make as many cartridges as they could at the time; for a few months they owned 100 percent of cart production in the world for this title, and that bet paid off very handsomely." However, while both the Sega and Nintendo versions of the game were massive sellers, the gaming press quickly picked up on the fact that the SNES edition was missing the vital ingredient that made the coin-op version tick.

"Once the games were released, the news about Nintendo censoring the game got out very quickly," says Peters. "Everyone then believed it actually hurt sales on the SNES, even though the SNES was the better playing and looking game of the two versions. If you wanted the gore, then you bought the Sega version. If you wanted the better playing and looking game, you bought the SNES. As a consumer, those were your main decision points. The SNES game played just like the arcade, except for the 'sweat' and Fatality changes; we had no say in Nintendo’s stance on gore, so we did the best we could to make the best game possible within the rules and constraints we were given."

Predictably, Carruthers has a slightly different perspective. "Obviously I’m going to be biased, but I can concede that the graphics may have translated better to SNES hardware. However, I don’t think that the SNES version faithfully represents the control and responses of the original and this is the central focus of this game. The Mega Drive version copies the original gameplay logic in most cases line-for-line from the original source code, and I think this results in a superior overall experience; this is what I’m most proud of."

Politicians will always jump on stuff like this for their own nefarious reasons. Certainly at the time, I would have used the 'Tom & Jerry' argument that this sort of depiction of violence was too far removed from reality to have any effect

Irrespective of their inherent strengths and weaknesses, both ports are fantastic interpretations of the original arcade machine, and they become even more impressive when you consider the incredible pressure the two teams were under to get them out of the door on time, as well as the relatively humble nature of the host hardware when compared to the coin-op technology of the period. However, you could argue that Mortal Kombat is better remembered for the fallout that occurred not long after its release. At the end of 1993, a U.S. Congressional hearing on video game violence took place and Mortal Kombat found itself at the centre of this storm, alongside titles such as the FMV-based Night Trap. The hearings would ultimately result in the creation of ESRB, a body devoted to applying and enforcing age ratings on video games, but at the time it's easy to see why the members of both Probe and Sculptured Software felt like they were at the centre of a witchhunt.

"Politicians will always jump on stuff like this for their own nefarious reasons," laments Carruthers. "Certainly at the time, I would have used the 'Tom & Jerry' argument that this sort of depiction of violence was too far removed from reality to have any effect. Of course, when I became a dad, my attitude softened and I was more aware of the effect of everything on children. Now my kids are older, and they have grown up with GTA – much to the disdain of other parents – and don’t appear to have been too badly affected by it, so I think I’m back in the 'Tom & Jerry' camp."

For Peters, the furore which gripped North America in 1993 was more keenly felt. "Sculptured Software was in Utah, which is one of the most conservative states in the country. There were bills introduced at the time trying to outlaw Mortal Kombat arcade games in the state – they failed but were still introduced. I was personally judged in my neighbourhood – and not in a good way – as the local kids told their parents what I was working on, and their parents didn’t talk or associate with us as a result. We knew their views as their kids would come by and while asking if they could play the game, they ask us if the views of their parents were really true. We quickly became the subject of judgment and speculation – drug dealers, satan worshipers, and so on."

I was personally judged in my neighbourhood – and not in a good way – as the local kids told their parents what I was working on, and their parents didn’t talk or associate with us as a result

Being mistaken for one of society's undesirables just because you worked on a video game isn't anyone's idea of a good time, but Peters says the whole process impacted some more than others. "It frankly didn’t affect me or the team much, but that backlash against the gore was indeed front-and-centre to us to here in Utah. We even had one programmer on the team that just asked us to not tell his family what he was working on; we were to say it was another project if they came in and asked. I personally didn’t care much about the violence as it looked pretty cheesy in the game, and that was the point; amplify violence to the point where it is not scary but actually funny. That was the game’s shtick essentially, and that helped it stand out in a crowded, Street Fighter II-dominated world. I still feel proud of the work we accomplished at that time, and took all that learning directly into Mortal Kombat II, in which we improved on all of our development processes, tools and designs." It's worth noting that the SNES version of the sequel retained all of the blood and Fatalities; the reaction to the original had clearly forced a rethink on Nintendo's part.

Since working on Mortal Kombat, Carruthers has held positions at Anthill Software and Climax, and now plies his trade at Sumo Digital. Peters moved to Kodiak Interactive in 1997 and has worked at GearWorks Games, Electronic Arts and TapStar Interactive, the latter being the studio he co-founded in 2014. Following the launch of Mortal Kombat in 1993, both Probe and Sculptured Software would continue to work with Acclaim, and the pair were eventually absorbed into the company in 1995 to become Acclaim Studios London and Acclaim Studios Salt Lake City respectively (although the latter was briefly named Iguana West). The London studio would be shuttered in 2000, while the Salt Lake operation lasted two more years. Acclaim itself filed for bankruptcy in 2004.

Mortal Kombat is remembered today for many different reasons; the joy of unlocking the blood with that famous code on the Sega edition; the closeness of the visuals in the SNES port; the sudden explosion of moral rage in December 1993 and – of course – the fact that it was a fantastic one-on-one fighter which offered home console players a genuine alternative to Street Fighter II. Looking back now, however, it's truly striking that two ports of the same game could be so drastically different despite being released at the same time – even more so when you consider that today, gamers debate over things like frame rates and resolution shortfalls when comparing PS4, Xbox One and Switch versions of the same game.

Having two different versions of the same game on the market at the same time was odd, especially on the very visible concept that made them different

"Having two different versions of the same game on the market at the same time was odd, especially on the very visible concept that made them different," says Peters. "I don’t think we’ve seen a similar situation since." For Carruthers, that Mortal Kombat could be crammed into a home console was the truly striking thing. "I’m more amazed that two such basic consoles were able to reproduce something from a much more sophisticated hardware platform so well; many games of that era would stretch the console to the absolute maximum. This is rarer with the current generation of platforms."

The contest between the Mortal Kombat ports has to rank as one of the most high-profile – and divisive – the games industry has ever seen; a perfect storm of hype, marketing, amazing programming and – of course – controversy, with the latter being perhaps the best way to sell any product.