These days, the Lord of the Rings video game licence is big business. Last year, Embracer Group purchased Middle-earth Enterprises, the Zaentz Company subsidiary that owns the video game rights to J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy world (along with the film, merchandise, and theme park rights) for an undisclosed amount – although there are reports it could take up the lion's share of the $788 million the company spent purchasing six businesses, of which Middle-earth Enterprises was just one.

Putting aside the recent disappointment of The Lord of the Rings: Gollum (a title which was in production prior to Embracer purchasing the video game rights), it's easy to see why the property is so highly valued in the realm of interactive entertainment; Tolkien practically wrote the rule book on high-fantasy settings and his influence can be felt through almost any fantasy movie, video game or book created in the past few decades.

While the current wave of popularity for both Lord of the Rings and its prequel The Hobbit can arguably be attributed to the phenomenally successful cinematic adaptations by Peter Jackson, Middle-earth is a location that has attracted the attention of game developers since the earliest days of the games industry.

Beam Software's 1982 ZX Spectrum adventure The Hobbit holds the distinction of being the very first game to be based on Tolkien's literary works, and it was swiftly followed by Lord of the Rings: Game One (1985), Shadows of Mordor: Game Two of Lord of the Rings (1987), War in Middle Earth (1988) and The Crack of Doom (1989). This flood of titles illustrates just how much of a fanbase was around at the time, even in the decades before Jackson's movies hit cinema screens at the turn of the millennium.

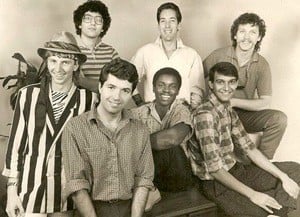

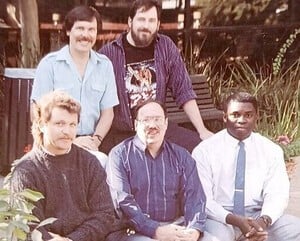

"Everyone was a big fan of Lord of the Rings," says Troy Miles, the former Interplay developer who worked on the American studio's 1990 video game adaptation of the books. Interplay boss Brian Fargo leveraged his intense affection for the series to convince the rights holders to permit him to adapt the books into a video game. "As part of my pitch to the Tolkien estate, I showed them some of my first programming that I had written on the inside flap of The Fellowship of the Ring," he says. "I wanted them to know how special the books were to me."

It's important to be aware that, at this moment in time, a Lord of the Rings video game wouldn't have had the consumer awareness that it would today. "Keep in mind that there were no smash hit movies at this time," says Miles. "There was a Ralph Bakshi animated film that came out ten years before, but it was not a blockbuster." (That film has gone down in movie history as a flop, even though it generated $32 million on a $4 million budget; the hatred towards it is generally down to the fact that it only covers the first two books of the series – The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers.)

Founded by Brian Fargo, Troy Worrell, Jay Patel, and Rebecca Heineman in 1983, Interplay was famous for its adventure titles and had scored hits with The Bard's Tale series, Wasteland and Neuromancer, the latter being a loose adaption of William Gibson's book of the same name, now considered to be a seminal work of sci-fi fiction. By the time the company came to release Lord of the Rings, it also had Battle Chess (1988) and The Adventures of Rad Gravity (1990) to its name – an indication that it was broadening its scope beyond the adventure genre.

Inteplay's J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I's origins actually go back to a Commodore 64 title called Secrets of the Magi. Fargo employed Jennell Jaquays to design this fantasy adventure, which would feature free-scrolling, real-time action rather than ponderous grid-based movement. It's not known if development actually got beyond the conceptualisation stage, but at some point, the decision was made to transfer the project to the Lord of the Rings property whilst keeping the C64 as the target platform. This version never actually saw release despite apparently being completed, and development was rebooted on PC.

Placing the player in the role of Frodo Baggins, J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I follows the storyline of the books reasonably closely; Frodo must recruit members of the "Fellowship" but is gifted with a surprising degree of freedom when it comes to exploring the vast world; it's possible to backtrack and revisit older locations, for example, often finding new narrative threads in the process. "Lord of the Rings used a game engine based on the one I wrote for Neuromancer," explains Miles. "It made it possible to break things down automatically and span across multiple floppy disks."

While the game adopts the familiar top-down viewpoint seen in the likes of the Ultima series, Miles is adamant that he and his team at Interplay weren't influenced by any other game. "The perspective was euphemistically referred to as 'two-and-a-half-D', which was pretty popular then," he says. "It had the plus that it could incorporate a large map on memory-constrained computers. Honestly, Interplay didn't try to imitate anyone."

While some of the earlier Lord of the Rings games used text parsers for their interface, Interplay's game was unique because it had both text input and an icon-driven system. "This was more a result of the constraints of the machines," claims Miles. "The 6502 computers had less the 64k of memory, usually about 32k of usable memory." As a result, it feels like J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I bridges a gap in the evolution of adventure games; as the '90s progressed, the notion of having the player input text and have to 'guess' the correct response became a thing of the past, and visual UIs powered by mouse control took over.

Although it wasn't the first game to include a day and night cycle – Konami's Castlevania II: Simon's Quest pulled the same trick a couple of years earlier – J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I's application of such a system gave it another layer of complexity. At night, enemies become more powerful, and players are more likely to be attacked by the infamous Nazgûl when the sun is set. "I credit Brian and others at Interplay for the day and night cycles," says Miles. "It is important in the books, since many of the enemies are most active at night, and night filled the Fellowship with dread."

Originally released on PC in 1990, J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I would later be ported to the Amiga, FM Towns and PC-98, with the Amiga port being handled by Silicon & Synapse, which would later become Blizzard Entertainment. When CD-ROM drives became popular with PC users a few years later, Interplay capitalised on the increased storage space to re-release the game, complete with Full Motion Video sequences lifted from Ralph Bakshi's aforementioned 1978 animated movie.

A second game, J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. II: The Two Towers, would arrive on PC in 1992 (with PC-98 and FM Towns releases coming a year later), but by that point, Miles had left the company. Like Bakshi's oft-maligned animated epic, Interplay's foray into the world of Middle-earth never got past the second book. He has no idea why a third game never saw release, but Interplay wasn't entirely finished with Tolkien's world, even if it didn't tackle The Return of the King – it loosely adapted the unreleased C64 version of the game for J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Volume I on the Super Nintendo, which was released in 1994. "It was rewritten from scratch for SNES," maintains Miles. "I believe they rewrote the game engine so they could use the game data and introduced compression to shrink the data's size." Interplay had also begun work on a NES version which was shown off in 1991 but was never released.

Miles no longer works in the games industry, but has very fond memories of his time at Interplay. "The team at Interplay was amazing," he recalls. "Being a startup, we were much closer than you could ever be at a big company. I wasn't the only minority. We weren't concerned about anyone's colour, religion, or anything else. Most importantly, you had good coding chops and an eager desire to do so. I would love to say I led a healthy work-life balance, but I was mainly about the code; we all were. My only recreation at the time was surfing. I would hit the waves a few times a month. Luckily our office was less than a mile from the beach, and we had a shower."

Looking back on his contribution to video gaming, he expresses fondness for those pivotal adventure titles he helped bring to life during his time at Interplay. "I like games that are more like novels and not too violent. I love that players would play the game for hours over many days, not out of frustration but for exploration. And I am still proud of the way we built fun games on constrained machines – the code for Neuromancer and Lord of the Rings was written in 6502 assembly language."