The marketing expert and former video game exec Mike Fischer may not exactly be a household name in the world of gaming, but we’d argue he has had a more exciting career than most working in his respective field.

Over the course of the past 35 years he’s been in the industry, he’s not only worked at some of the biggest names in gaming, including Sega, Namco, and Xbox, but has also had a front-row seat for some of the most significant events in video game history — from witnessing the birth of Sonic the Hedgehog in his early days as a junior marketing assistant at Sega of Japan to helping to release the Xbox 360 into the marketplace as the general manager of Xbox’s US Marketing.

As a result, we reached out to him earlier this year to see if he would be open to sharing some of these memories he had stored away, and we were incredibly grateful when he eventually replied, agreeing to go over some of his favourite anecdotes with us.

During our conversation, we talked with Fischer about how he wound up working at Sega of Japan in the early ‘90s, his adventures in advertising at Namco including his involvement in a now infamous magazine ad that comapred Klonoa: Door to Phantomile to a sexually transmitted disease, his experience with butting heads with Sonic co-creator Yuji Naka, and what it was like to launch the Xbox 360 in Japan.

Without further ado, let's dive in...

Time Extension: In the past, I've heard from former Sega colleagues that you moved to Japan straight out of college. I'm curious, could you talk a little bit about why you ended up moving to Japan, and how, from there, you decided to pursue a career in games?

Fischer: So, my journey started a lot earlier than most people know. I started at university in 1984, and I started as an electronics engineering major. My university was really geared towards military technology. So most of the graduates from electronic engineering typically got very high-paying jobs in the defence industry.

I realized in my first year, though, that one, I wasn't a good engineer, and two, I didn't want to work in defence; I didn't want to be working on things that kill people. So I sort of had an identity crisis.

I asked myself where I wanted to take my life. And I thought, 'Well, the opposite of what I'm doing now is something that brings people joy.' So I really started targeting the toy industry. In senior year, you have to write a senior thesis to graduate, and I did mine on "Econometric modelling and analysis of revenue in the toy industry", having moved from an engineering major to business. And in the course of that research, I realized that the toy business had really hit a dead end at this point, because video games were really taking over, and well, I love video games, right?

I'd played every video game since Pong, I had the Atari 2600 in my house, and I went to the arcade at least a couple of times a week to play the old coin-op games. So I got the idea in mind that I would either work at Mattel, which is the toy company in Los Angeles, or Nintendo. Those were the only two choices for me. As I was getting ready to graduate, though, I realized I had no hope of getting a job at either. I had my college degree, but I had no experience, and the economy wasn't particularly good at that point. And I heard that you can do this thing, teaching English in Japan.

I literally wrote away and bought a pamphlet on what to do. And I ended up getting a job teaching English in Japan, which is, if you know anything about teaching English in Japan, not a great job and not a great lifestyle. But it got me to Japan, which is where I wanted to be.

Time Extension: From there, how did you end up getting the job at Sega of Japan?

Fischer: I spent two years teaching English unsuccessfully, and while I was doing that, I was really studying the language, and knocking on the door of every toy store and every video game company I could. I guess, at that point, Sega was so desperate, and their standards were so low, that they even hired me. Because at that point, my Japanese was still pretty bad.

There wasn't a title for my job. I was just a working-level employee. And I ended up working at Sega's Japan headquarters for four and a half years, then I transferred to Sega of America for another two and a half years, so sort of seven years altogether. I first worked in the consumer division right as the Mega Drive was launching in Europe, right after the Genesis had launched in the US. So I was there for that whole rocket ship ride. I remember when Tom Kalinske joined, and I remember when Sonic the Hedgehog first came out.

Time Extension: Can you share any memories about Sonic? Do you remember how that first came together or what the launch was like?

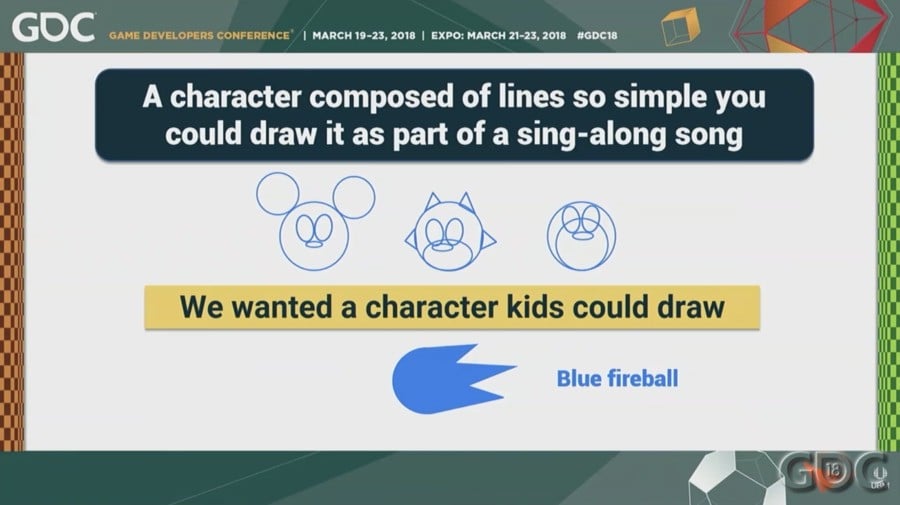

Fischer: It was relatively early in my time at Sega, and they had an announcement that we wanted to make "a Mario Killer". They invited every employee in the company to submit their game ideas, and I had a couple of game ideas.

I was working basically as a marketing assistant, but it wasn't limited to creative employees; anyone could submit. My ideas were terrible, and I never did anything with them, though.

Anyway, one of the ideas from elsewhere in the company was obviously the Sonic the Hedgehog concept, and they put together the dream team of Naka-san, Ohshima-san, and Yasuhara-san to make it.

I didn't know Yasuhara-san, but I actually got to know Ohshima-san casually, and that's where the anecdote came from in the book Console Wars. I asked Ohshima-san what his inspiration was, and he said, 'Oh, I put the head of Felix the Cat on the body of Mickey Mouse.' Now, he eventually told me later that he really put it on the Japanese character Doraemon, but he wasn't sure that I knew who Doraemon was, so he said Mickey Mouse.

Also, as an aside, the reason that I even agreed to talk to the Console Wars author was that I was so unhappy that Yuji Naka had taken so much credit for so many years that rightly belonged to Ohshima-san. So I wanted to share my story with him.

Time Extension: Do you remember what the initial reaction to Sonic was inside Sega?

Fischer: Well, what was interesting was that when the very first concept of Sonic came out, not everyone thought it was great. There were some people who I will not name, including people at Sega of America, who said, 'I don't get it.' We got this fax back from them that said, 'We don't get it. You know, hedgehogs are slow, not fast. This thing is blue; hedgehogs aren't blue. And, he's a sprite character on a sort of polygon-looking background — that's a mismatch.'

So they were like, 'We have some concerns.' And then I think about the time the alpha code or the first preview of Green Hill Zone came out, they wrote back, and said, 'We're sorry, now we understand what you're talking about. This is going to be the biggest thing ever.' Then they were all on board. So that was the funky beginning of Sonic the Hedgehog.

But I think it was really to the credit of Madeline Canepa and Al Nilsen on the marketing side, and especially Tom Kalinske, to come back and say, 'This is the tool we're going to use against Nintendo.' Because before Tom, Tom's predecessor had basically said, 'Look, until we get down to $99, the Genesis is really going to be sort of a high-end hobbyist's machine. There's not really a lot of mass market potential.' It was Tom who really turned that around.

Many of my friends in the toy department already knew Tom from his Mattel days. They were excited and thought, 'This is the best guy in America to lead us,' but they also thought, 'What horrible scandal did Tom get involved with that he joined Sega? He's too good.'

Time Extension: Looking up information about your career at Sega, I was able to find your name in a few credits for a few Sonic and Disney games released for the Pico, but your profile says you also supported other Sega consoles/accessories like the Master System, Genesis, and Sega CD. Could you talk a little about what games you worked on and your role?

Fischer: So keep in mind when I joined Sega, I was 24, so I was incredibly junior. But to give you some more background, fairly quickly after joining Sega, my Japanese improved enormously, so just because of who I was, a lot of times I was the youngest person at the table by 10 or 15 years, and sometimes I was the only non-Japanese person at the table. I was really fortunate that I was able to see things that ordinarily someone at my junior level wouldn't see.

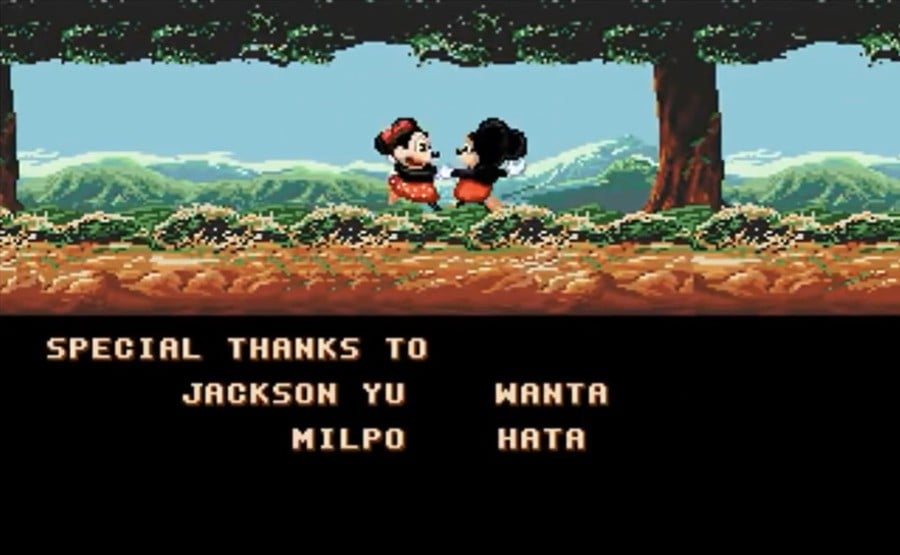

So I was involved as a sort of facilitator and helper for all of their big projects. But you have to bear in mind, I was a very junior person. I was not the leader for any of these, at least at this point in my career. And also, you were not allowed to simply put your own name in the credits on games back in those days. So the first game that someone put my name in was Mickey Mouse and the Castle of Illusion, but they couldn't put my own name in there for some reason. My son had just recently been born, though, so I asked them to put my son's name in it instead.

So if you go through the credits, everyone's name in the credits is a nickname. So Emiko Yamamoto, who was the lead designer of the Mickey Mouse games, was called Emirin, and my son's name was put in as "Jackson Yu".

To this day, I'm still friends with and a fan of Emi. She's still in the business and still incredibly talented. She was the Disney producer for the Kingdom Hearts games, but she's now a senior executive at Amazon Japan.

But, just to go back to your question, the consoles I probably worked on most closely were the Pico and the Game Gear. The Genesis and Mega Drive were already out the door. Then, by the time Saturn came out, I was working in Sega's toy division.

Time Extension: Sega was on something of a rollercoaster ride during that first period in which you were there. It went from almost being a non-competitor to Nintendo to the mainstream success of the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, and then later came back to earth with some high-profile missteps and mistakes during the 32-bit era. What do you feel went wrong for Sega following the success of the Mega Drive/Genesis?

Fischer: When I left Sega, Irimajiri was the CEO; Tom had left, so Irimajiri was running both the US and Japan at that time, and he was based in the US. So I went to tell him what I thought of the company and that I was leaving to go to Namco. The way I framed it with him was, 'Sega cannot compete in this new era on the scale of Sony or any of these giants."

I told him, 'You need to get out of the hardware business. Sega needs to become a software publisher.' I said, 'I'm going to go learn third-party software publishing, and I'm going to work at Namco. If you ever decide to take my advice and become a software company, I'll come back, but I need to go there first.' And he was very gracious. So that was the first thing — we just couldn't compete at scale.

Another thing was, I think SEGA had just lost a lot of its focus. We had the Pico, the Game Gear, the Sega Genesis, the Menacer, the Sega CD, the Sega Channel, Sega VR, the 32X, and the Saturn. We were just so distracted by so many different things because the company was making so much money at that point, so we could afford all of these crazy new ventures. But we didn't have the organizational ability to focus on one or two things and do them well, which Nintendo always had the discipline to do. I think that hurt us, and it hurt our chances.

Time Extension: As you mentioned, you eventually left Sega to become a director of marketing at Namco in the US. What attracted you to Namco and that position in particular?

Fischer: It was simply that I wanted to learn and understand third-party software publishing. Namco would allow me to leverage my Japanese business experience and my Japanese business skills, but then also give me the chance to develop more on-the-ground American marketing skills.

I'd previously done some marketing at Sega, but I wasn't there because I was such an excellent marketer. They just let me do the marketing because I was a convenient tool for them across their U.S.-Japan relationship, and I really loved product marketing and product management.

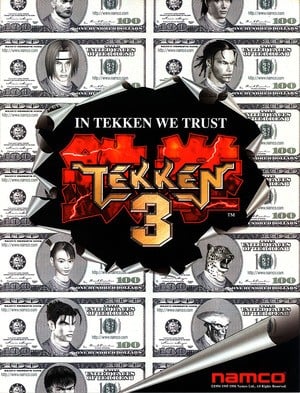

Another thing was that, at the time, Namco was an exciting company. They had just shipped the first wave of sort of second-party titles for PlayStation, including Ridge Racer, Air Combat, and Tekken 2, and right as I joined, they were getting ready to launch Tekken 3 in the arcade, so business was good. There had also been a lot of kind of animosity between the Japanese and the US teams at Sega, particularly at the end; sometimes it almost felt like an adversarial relationship. There was much less of that at Namco. It was a much smaller and much tighter organization.

Time Extension: One of the major games you were involved with launching at Namco was Pac-Man World, which proved to be a very important title for Namco Hometek, giving them the freedom to pursue more in-house projects. I'm wondering, do you have any memories of that game? I remember its marketing campaign was pretty crazy and featured celebrities like Mr T and Verne Troyer.

Fischer: Yeah, that was really fun. It was just like, you could get away with so much. I remember one time we had an underwater game with the Treasures of the Deep, we had a shooting game with Time Crisis, and we had Ace Combat. And I saw my boss in the coffee room. He's a much, much older guy. I said, 'Hey, Homma-san, listen, would you be okay if we decided to do a paintball, scuba diving, and car racing press event for the media?' He's like, 'Whatever you want. I don't care.' And we did.

We took people paintball, scuba diving, and skydiving. It was just whatever we wanted to do. There was just so much freedom, and decision-making was so easy.

In fact, there were only really a few times I remember where the answer was no. I remember once I said, 'I want to make a Pac-Man gumball machine as a giveaway item.' Like, put little yellow gumballs in a Pac-Man machine. And my counterparts at the marketing department at Namco headquarters were really nice. They just explained, 'Mike, you will be fired if you try to propose this.' They said, 'You have to understand how beloved Pac-Man is to our chairman, president, founder, and CEO, Masaya Nakamura.' And she sent me an example to illustrate this.

Every summer, Namco sent out postcards to all of its customers and friends, and she had sent me two postcards of Pac-Man scuba diving with a little scuba mask on. She said, 'The chairman was so upset when he saw the original, he made us go to the post office and get the postcards back before they were delivered and reprint them.' She said, 'Can you tell me what the difference is between the two?' And I couldn't tell. So she goes, 'If you look really carefully at the way his mouth sort of forms around the scuba mask, you can see his mouth is slightly deformed.' The chairman was apparently furious. He had told her, 'You can't do that with Pac-Man.' So she warned me not to bring her any more crazy Pac-Man-themed giveaway items.

Time Extension: I remember hearing from former Namco staff that the project was in development for a while and was even rebooted at one stage (the original title of the project being Pac-Man Ghost Zone). Do you happen to have any memories of that?

Fischer: Oh yeah, it was a shit show. So the first time we went with the original designer to show Pac-Man to the chairman, we got the game set up in his office, and the designer just froze. I was supposed to be there as the translator, and he couldn't talk, so I was just winging it, saying things like 'Oh, he's jumping, and now he's rolling.' The game at that point just wasn't gelling, right? And so, the chairman just looked up — he didn't yell or anything — and he just said in a very calm voice, 'This game is not ready to show to the chairman of Namco.' After that, they reorganized the team, and they put some different people in charge.

If you've ever come across Scott Rogers, he became one of the lead designers at that point. I went on a media tour, and I brought Scott with me, even though I didn't know him all that well. I had been saying to the team, 'We need somebody who can talk to the press. No one wants to talk to the marketing guy.' So I took Scott to go along with me and talk to the media, and it was like a duck to water. This guy who'd never spoken to the media before was just magnetic. So I took him everywhere: CNN, Fox, the Today Show. He was just very talented and very creative, and he could turn on his smile and talk and ad lib. I do have one good story about the media tour if you'd like to hear it.

Time Extension: Sure! Go ahead.

Fischer: So, we hired a guy in a mascot suit for Pac-Man the tour, and we had one time we were supposed to be on Fox Morning News live, and the truck carrying the Pac-Man character got pulled over on one of the bridges coming into Manhattan, and the driver had a suspended license.

The producer for the Fox show was just like, 'You fuckers. You're late. I can't believe this. I slotted you guys in as a favour, you're never gonna fucking be on this show.' He was so upset. And as he was saying this, the host went, 'And coming up after the ads, Pac-Man, 20th anniversary.' So he had to put us on, right? Somehow, we got the suit, the guy put on the suit, but he was too big to get through the door. We had to run him around the other way, and we got on the set like with like five seconds before the camera went live. That was how crazy everything was.

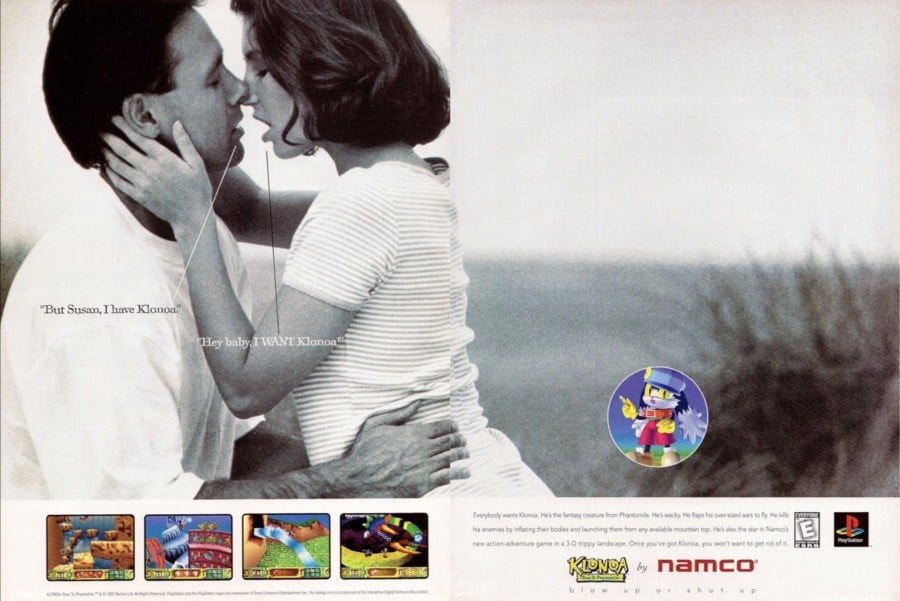

Time Extension: When I first reached out to you, one of the main things I mentioned was Klonoa's marketing campaign. It had a bizarre advertising campaign in the West that included a now pretty infamous print ad, where it essentially compared the name of the character to an STD. I've seen people curious about how that came about. Could you talk a little about what the thinking was there?

Fischer: Sure, so, they showed us the game and the character, and the game had some issues that I'll talk about, but the biggest issue was just that the name of the game was Klonoa.

I took a trip to Japan to specifically talk to the team and said, 'You cannot call this thing Klonoa. It sounds like some kind of STD. It sounds like something you talk to your doctor about.' So I looked up the word in Japanese, and I begged them, 'Please just call it anything else.' The creative leader of the project was a legend. He had previously worked on games like the original Ninja Gaiden for the 8-bit NES, and he had just been hired by Namco, so the thinking was you can't hire this superstar and immediately tell him he can't do what he wants. I tried my best to convince him to change it, but he just would not budge, and the name ended up sticking.

From there, I then worked with an incredible advertising agency called Bob Kilburg & Associates, based in San Francisco. Jill Zook was my account manager, and she was really good at translating between the business side and the creative side, while Bob was just a creative genius and had a wacky sense of humour. Anyway, they heard my story, and they just played with it, and that was that. That was the campaign they came up with, and I loved it. So it was sort of my passive-aggressive response to the name, and we thought it might generate some attention, which it has.

The other thing I wanted to tell you about Klonoa was that it was a shooter on rails, right? So it wasn't a particularly rich gaming experience. Because of that, I was constantly thinking away on a way to position it that would be a bit more exciting. I was thinking and thinking and then one day, I woke up, and I was so, so proud of the idea that I came up with.

I went, 'We're gonna create a new term, we're gonna create a new genre, we're gonna call it 'Guided 3D'. I thought, 'I'm a genius. I am so smart,' and so we called it Guided 3D on the packaging. But then all of a sudden, I remember opening up a magazine* and reading this review. They had the cross reviews, and one of them said something like, 'I don't know what stupid marketing hack came up with the term Guided 3D, but this is just a shooter on rails.' Like, they gave it 4 out of 10. So it was a very humbling experience for me that this genius idea was immediately unmasked and mocked.

*[Editor's Note: Fischer believed the magazine mentioned here was Electronic Gaming Monthly, but checking its review of the game in the March 1998 issue, the publication actually gave the game 9/10 across the board. Also, something else we need to highlight is that Fischer refers to the game as "a shooter on rails", but the game is actually a 2.5D platformer, suggesting his memory of Klonoa may be a little fuzzy, or he potentially misspoke.]

Time Extension: After four years at Namco, you ended up going back to Sega in 2001. What made you decide to go back? Other than making a promise to return if they someday decided to go third-party.

Fischer: I got to know the Sega team because we did Soulcalibur for Dreamcast. So, I would occasionally go up to San Francisco and see some of the Sega team, and I got to know Peter Moore pretty well, and we worked closely together on the publishing. Then, one day, a phone call came.

I don't think Peter was allowed to call me directly, but instead, he had a mutual friend of ours call and say, 'You should give Peter a call.' And so I called him up, and he said, 'Hey, we're going to abandon hardware. We're going to go back to software. And your name came up as somebody with experience. We need somebody who knows Sega, knows Japan, and knows third party, and everyone says that's you.'

When they called me, I'd been at Namco for four years, and I had kind of hit a roadblock there and had learned pretty much everything I was going to learn. There was not really a lot of upward opportunity for me in that small organization, and I had already promised to come back, right? Sega's like the mafia; you can quit, but you can never really leave. So I went back and led the non-sports stuff, but immediately, the big issue I had was that Sega was historically very competitive. They had run some pretty snarky ads against PlayStation, and they had also always been poking Mario in the eye.

So I had to go back to all those companies and say, 'Listen, we're struggling. We don't have a lot of marketing budget. We really need your help.' Andy House was the head of marketing at PlayStation; he went on to become president of PlayStation America and then president of PlayStation Worldwide. He was very gracious and helped us a lot, even though we had once been fierce rivals. Nintendo was also gracious, too. In fact, we took the Sonic mascot character up to Nintendo for a little press event, and they had the Mario mascot character waiting at the door of Nintendo America.

The actors were in their costumes, in character and hamming it up, and they hugged each other at the door. Mario opened the door and let Sonic walk in, and I mean, honestly, my eyes were starting to tear up a little bit after all I'd been through to see that moment. The Nintendo people were just so kind and so gracious and let bygones be bygones, and it was just a beautiful, wonderful relationship from then on.

Time Extension: How well do you think Sega adapted to becoming a third-party developer during this period?

Fischer: Well, it depends. I think the best part of it was the Sonic and Nintendo partnership, because I know Naka-san had always wanted to work with Nintendo. He had applied to Nintendo, and he didn't get in, and then applied to Sega and got in. So he'd always wanted to work there, and he really put Nintendo on a pedestal. So he was very happy putting the Sonic on both the GameCube and Game Boy Advance.

The bigger issue, though, which is the one that Peter has talked about in his book, is that at Sega, there was just, at this point, a mindset that came from their arcade legacy and the days when they were the platform holder, where they just felt everything would sell just because they were Sega. The Japanese studio heads had, at this point, become all semi-autonomous business units to give these creators more ownership and motivation, and they put a system in place where they could borrow money from the parent company to build the games that they wanted to build and then would have to sort of repay the loan. Now this was all internal, right? So it was more of an accounting conceit. They weren't actually independent companies. But they had let the studio heads run them as if they were.

So what happened was basically it just allowed them to make all of these vanity projects because they had always been just company employees. A few of them, like Jet Set Radio, Phantasy Star Online, and Panzer Dragoon Saga, were breakthroughs. And then you also got some crazy stuff like Seaman that might not have been super commercially successful, but creatively was there. But then, a lot of them were just, 'Let's take our old arcade hits and just port them as is,' and there was this expectation that those games would sell.

As Peter tells in his book, he tried to tell them the industry was changing but failed to get his point across, so he called me from the plane [on the way back from his own meeting with Sega Japan] and asked me to help. He said, 'We've got to deliver this player manifesto. We have to help them understand we're in a new world. They need to realize Grand Theft Auto is attracting a new audience, and that people are playing these games for hundreds of hours. So we're currently in a situation where people will buy our games on Tuesday, play them, and then sell them back on Sunday to GameStop. So no one is making money.

Essentially, we were trying to try and convince them that they need to make multiplayer games where people can just compete against each other forever, or they need to be longer, narrative-driven story games that are a rich, deep, immersive experience, and explore adult themes. That way we could get around some of the problems were were having.

Time Extension: How did they receive you after Peter's meeting? Peter famously recalls telling Yuji Naka to "f**k off" in his meeting, so I imagine things must have been pretty tense when you showed up not long after.

Fischer: It was way worse. Of course, Naka-san was the most upset because again, he really believed in that Disney-esque family wholesome environment, and his games were the only ones that were ever successful.

He said to me, during the meeting, 'You? You're telling me how to make games? Why don't you just tell us to make porn? That's what you want.' And he was literally frothing at the mouth. I swear he had these little spit bubbles bubbling up at the corner. He was so angry.

I tried to be positive. I said, 'Look at what Nagoshi is doing with Super Monkey Ball. It's innovative and has a ton of replay value. It's arcadey in some respects, but he gave us tons of marketing assets. This is what we need to be doing.' And I remember Yu Suzuki was just like, 'Hey, I do that too,' and they pretty much ate me alive.

One problem I was trying to explain all this in Japanese, and my Japanese is good, right? But it's not native-speaker good. And so I probably didn't come across as articulate as I could have. The funny thing was, though — and this had nothing to do with me — but Nagoshi later went on to make the Yakuza games after that, which was exactly what I was asking them to do.

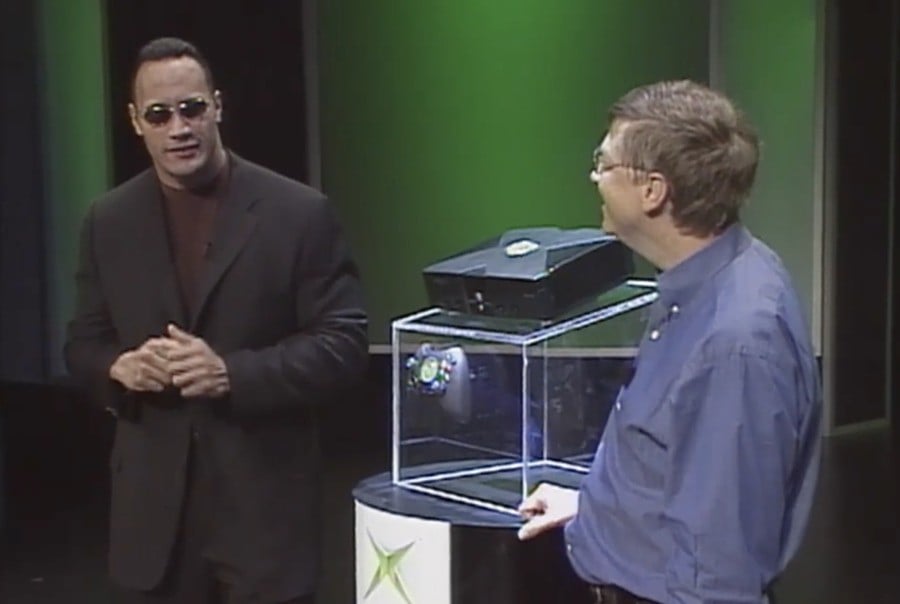

Time Extension: Your second stay at Sega was even shorter than your first. In total, you stayed at Sega for just shy of three years in total, before leaving to join Microsoft. Why did you decide to leave Sega again? Was Peter the one who approached you to become a General Manager of Marketing at Microsoft?

Fischer: Peter left and called me. I think he only brought two people from Sega. He brought the media planner, who was just a superstar, and then me. As far as I know, I don't think he brought anyone else over.

Xbox was just in a horrible condition in Japan, and they'd had a really bad restructuring, and let a lot of people go, and a few other people kind of left in disgust at that, because layoffs even now are rare in Japan, but they were even more rare then.

Microsoft had also just handled it in a very corporate way, where there were lawyers in the room. It was 'Hey, this team goes there, and that team goes here; if you're going to be let go, go to this side of the room if you're going to stay, go to this side'. It was very dry, and it just wasn't the way that was done in Japan. A lot of these people were marketing people, so they immediately went to the media, and the media covered it in this very salacious way, like, 'Oh, typical American company, no wonder Xbox is failing when this is how they treat people.'

They had even had people who had accepted positions at Xbox at the time, and then these media stories ran, and they unaccepted. So they had me go over there, I think, because they couldn't find any qualified Japanese people willing to run into this burning house.

I was hired by Peter and then sent to help put the Xbox to bed, and then help get the Xbox 360 ready to launch.

Time Extension: One of the jobs you had at Microsoft was launching the Xbox 360, including in Japan, where the original Xbox had failed to make a dent. In your opinion, what made the Japanese market so difficult for Xbox to crack, and where did it go wrong?

Fischer: There's a lot of conventional wisdom about what went wrong with the original Xbox, and I think most of it is correct.

It was a team that had never launched a product together — not in the U.S., not anywhere. It was a passionate group of people who really cared about what they did, but they had never done anything together before. It was hard enough in the U.S. I mean, the original Xbox wasn't a big hit in the U.S. or Europe, so it had all of those obstacles of a first-time-out-the-door consumer product from Microsoft. But then, when you consider the Japanese market, Japanese tastes in games were very different.

The way that I compare it is, if you have cartoons and anime, they mean very different things, right? A cartoon is Bugs Bunny or Mickey Mouse. Anime is Akira or Miyazaki's movies. So they use the word "youge" (洋ゲー), which means Western game, and they think about it the same way Americans used to think about anime. So we had some Japanese content, but no major Japanese developers putting their bigger teams on our consoles, besides Dead or Alive 3. So we were selling a lot of games that were really not a big fit. Also, when it was launched, it was a big black console that sort of looked like a big American Cadillac driving down a little Japanese street, and it played into a whole bunch of stereotypes.

There were also other problems, too. Japanese gamers also weren't happy that there was a minor issue where some of the discs would get cosmetic scratches on them. So we had this issue where once the disc was done spinning, and it dropped down into the tray, the leftover inertia of the spinning put some cosmetic scratches on it. It was just one goddamn thing after another, but what was wonderful was that the team getting ready for Xbox 360 really took it to heart. And they came back to us, and said, 'Help us learn what we need to do to make the Xbox 360 do better.'

They even came over and did ethnographic studies where we brought them into Japanese homes and talked to the gamers in their homes. They would say, 'Look how small my apartment is. I roll up my futon, put it in the closet, take my Xbox out, and play. I literally have to shuffle my furniture around.'

So they just worked so hard to get it right. We also took the developers out and explained the strategy, and we worked hard with Sakaguchi, the creator of Final Fantasy, and some others to try and get them on board. And it was modestly successful in Japan, as a result of all this.

It wasn't a big hit by any stretch, but I think it was a real testament to the headquarters leadership and to Peter's leadership that it was really dedicated to doing what we needed to do to break through in Japan. Not because the Japanese market was so important, but because there was a sense that if we didn't at least have a reasonable market presence in Japan that Japanese developers would never be motivated to support our platform just based on the sales in the rest of the world.

Time Extension: Is there anything you’d change about the Xbox 360 strategy in Japan now looking back?

Fischer: You know, we really learned our lessons well. And I think we did the best with what we could. The easy thing is to say, 'Oh, I wish we had greater resources to do more,' but we were already way over-resourced. Compared to the sales forecasts, the money that was being spent on development and marketing was really more than I could have asked for. And we had a team of people, 95% Japanese, who really put their heart into it and really cared.

We also had some great developers, too, like Dead or Alive's Tomonobu Itagaki, who just passed away — god bless his soul. He became a dear friend of mine through the challenges we had bringing that game to the market and through talking through the differences between East and West views. I learned a lot from him, and we became lifelong friends as a result of that. He wasn't the only one, either. Sakaguchi was another very difficult developer to work with, but difficult, not because he was a jerk, but because he was a genius with a vision, right?

He just had a strong vision, and it was always my job to keep him on target and on the timeline and on budget, which was not always easy to do. I think Blue Dragon had like three DVDs. He wanted more. That was his compromise.

Time Extension: Obviously, you’re still working in the games industry to this day. What still excites you about working in this particular industry all these years later? And what are you up to now?

Fischer: So, I was at Epic Games, working on Fortnite, but I now work with Krafton as an independent consultant (gamegoglobal.com). So, for example, when Krafton acquired Tango Gameworks from Microsoft, that was me as the matchmaker between the two companies, for example.

Elsewhere, I also split my time doing several different things. I work with big, large companies to help them grow their global presence, and I also help Western companies expand into Asia, and I help Asian companies expand outside of Asia.

So I work with startups, help them fundraise, and help them with their strategy. I always explain to them that Van Gogh died penniless, Rembrandt died poor, and Monet died a multi-millionaire. My point is that you can't achieve your full potential unless you really understand business dynamics. I also spend part of my time as an educator and evangelist for game development.

I've been to Kazakhstan five times, Uzbekistan twice. I've been to Azerbaijan, the Republic of Georgia, the Philippines, and Cyprus. And I just go and speak to the next generation of game developers and try to share some of my insights on how they can go from being a scrappy indie to a global influence. Because I think that tools like Unity and Unreal Engine, and then distribution like Epic Game Store and Steam, are allowing teams from outside the traditional gaming areas to tell their story to the rest of the world.

And a video game today will touch more people than any book, any movie, or any song ever can. We're a global tribe. No one cares where your game is made.