There are few British video game developers (still working today) who can claim to have quite as interesting or as impressive a career as the Llamasoft founder Jeff Minter.

For the last four decades, he has endured all manner of incidents and setbacks the industry has thrown at him — and, through all that, has managed to stay remarkably true to himself, building exactly the kinds of experiences he wants, without compromise or defeat.

It should probably come as no surprise, then, that his work has wound up attracting the attention of documentary filmmakers, video game developers, and journalists, with all of the above wanting to understand how someone so far outside the corporate bubble — and with so little interest in market trends — could survive in such a volatile industry.

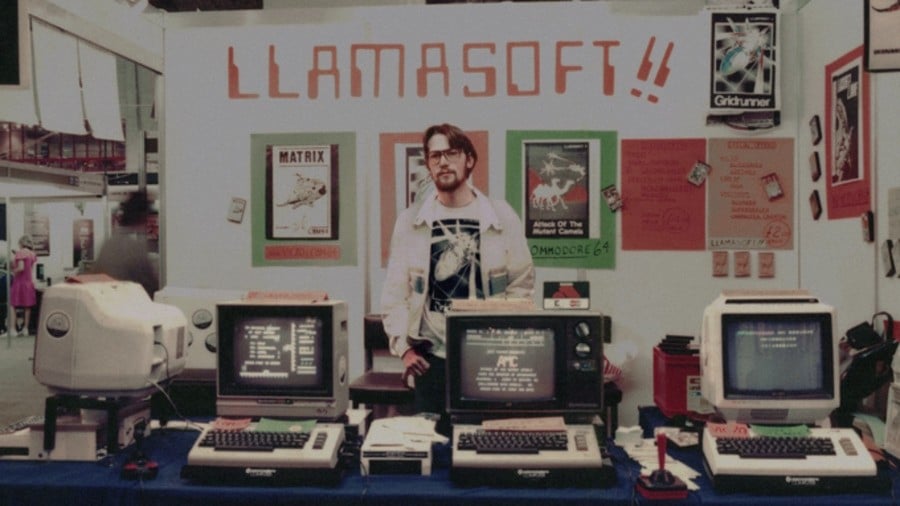

In 2023, Digital Eclipse released the playable documentary Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, which sought to answer this question, among other things. It provided a remarkable overview of the artist's career, covering some of his earliest work on the ZX81 through to his acclaimed 1994 shooter Tempest 2000, for the Atari Jaguar. This served to introduce his work to a wider audience (including many in the US) and helped to explain Minter's appeal to the uninitiated through documentary footage, archive material, and playable versions of some of his most popular titles.

However, according to the documentary filmmaker Paul Docherty (who provided the footage for the game's documentary featurettes), it represents only half of Jeff Minter's story, with his upcoming film Heart of Neon aiming to further demystify the artist by looking at his remarkable relationship with his fans.

With the Kickstarter for Heart of Neon's Blu-Ray being live, we spoke to Docherty to learn more about this documentary, what has gone into making it so far, and how it differs from what has come before it.

Time Extension: To start, it would be great to ask you - how did you discover Jeff's work to begin with?

Docherty: Oh, I mean, the first computer I owned was a VIC-20. He was one of the first game developers whose work I bought.

The first game I got was Wacky Waiters by Imagine because I was seduced by the airbrushed art. But the game was [not so great]. And then I don't know if it was the next game — but it was fairly early on — I bought Abductor, which was close enough to Galaxian for me to be into it. It felt like Jeff was coming from a place that I instantly got, which was I like the arcade stuff and I want more of that at home. So when I saw Grid Runner I was already pre-sold and that really nailed it. That was the first time I played a game that sounded like an arcade game at home.

So I was familiar with Jeff's work early on. I was on board for all of his shtick — He was in Zzap Magazine, right? And I even had the cassette for Ancipital before I got the Commodore 64 to play it on. I mean, I was a huge fan. And then I just moved away, right? Life changes. Every so often, I'd see something of Jeff's surface in my environment. Like I had a PC and Jeff's game Llamatron was on that. Or Space Giraffe was the next one on Xbox 360.

Time Extension: It seems like that's the perception that a lot of people have about Jeff's career is that there are periods where he kind of goes in and out of the mainstream or vanishes off the map entirely to work on something really obscure that never sees the light of day. There was the Konix Multi-System and the Atari Panther (both of which never saw an official release), and later on, he went on to work on other unusual platforms like the Palm Pilot and the Nuon. If you're not paying close attention, he's a hard person to keep tabs on.

Docherty: It's interesting hearing you say that because the film Heart of Neon was made from his perspective, and, from his perspective, he never stopped — he was just doing his own thing. He never cared about the mainstream. He does not, to this day, care about the mainstream. So he wasn't falling off anything. He was just following his muse. He was doing what interested him, working with new technology.

Chasing mainstream attention and getting a top-10 hit. It was not on his radar. So he never quit. I mean, when he was doing the Palm Pilot stuff he was not long back from working for Atari in California and the world had rotated a couple of times since he left. He was doing shareware when he left to work for Atari. When he came back, that was not really a thing anymore. And he was looking for 'What can an indie dev do now?' And the Palm Pilot was there. So he was ahead of the curve a bit.

I mean, he's sort of like that, you know. He was doing social media and live journals before social media was a thing, right? He was doing the mobile market X number of years before the Apple Store made that a thing. His instincts were correct, but his timing was terrible. That's sort of the Jeff Minter story. It's not that he dips in and out of the mainstream; he's just out of sync.

Time Extension: How did the idea of the documentary Heart of Neon first come about? We've heard you talking about the project for a few years now and we're curious when the journey actually started for you.

Docherty: To answer this, it requires talking a bit about me. So I was involved in game development back in the mid-to-late '80s, and a little bit into the early '90s. I was a game graphics designer and there was a tectonic shift in the business and it went more corporate and people were consolidating and I didn't have a good home. So I moved on. I became a film student and ended up working at a documentarian's company. His name is Ken Burns — he's well-known in the States.

Anyway, I was working there, I became a professional filmmaker, and I'd been casting about for a story. I'd been working for other people, but I wanted to make my own thing. The idea I had in mind was I wanted to relate the version of game development that I had experienced in the '80s to people who are now experiencing AAA games, where there are legions of developers whose specialization is [super granular like foliage]. And it wasn't until like a cohort of mine, the game developer Gary Liddon, said to me, 'Well, you should do a documentary about Jeff Minter, because his story pretty much spans all of like home video game market' that the idea first came up. And the more I thought about it the more the idea stuck.

Time Extension: Did you have any goals in mind when you initially set out to make the documentary? Or any questions you wanted to have answered.

Docherty: So there were two questions specifically I wanted to ask. One, how can a guy as left field as Jeff survive in an industry for four decades when the industry doesn't really care for idiosyncrasy and eccentricities? And the other question was, why does the game Space Giraffe exist? Heart of Neon answers both those questions. And the answers I found were completely unexpected.

I mean, I originally wanted to go in to make a film about the history of the video game industry, and how it evolved, and then tell Jeff's story in parallel. So the conceit was like, "Jeff is video game history", which is daft. But that gave me at least a blueprint as to how to structure the interviews and move forward.

And what emerged out of that was that I ended up being surprised by Jeff's relationship with his audience. I don't know if it's unique, but I've never seen it before. It's more like a fan's relationship with a band.

Time Extension: How did you approach Jeff to talk about the fact that you wanted to make a documentary about him? What was his response?

Docherty: So it's no secret that documentary film is all about access. And luckily, for me, I had an in. I was friends with Gary Liddon from way back, and Gary had become really close friends with Jeff after I moved to the States. So he was the one who suggested the idea, and he was the one that I contacted to say, 'Right, let's make this happen.'

He got in touch with Jeff — well, it was Jeff's partner, Giles really. And they contacted me via Zoom and Jeff got on the call and we talked about it. Pretty much straight away, Jeff said, 'Yes'. But then it took 18 months to agree on a date for me to come to the farm. So it didn't take off straight away.

The reason it took so long is there were a whole lot of different things that were happening, which are all explained in the film. TxK had not long happened and Jeff was in the middle of making Polybius, and he had a lot at stake because he hadn't made any significant amount of money in a while. So I backed off because I didn't want to push my way into the scenario where he was stressing about money and it be a terrible interview.

So I waited for Polybius to be finished and I waited and I waited and I kept nudging them. Then, eventually, it happened. And it was fine because Jeff's great on camera. It was just all about getting him to commit to a date.

Sorry, what was the question again? (laughs)

Time Extension: We were just wondering, what was the pitch to him? What did you tell him you were gonna do with the story to convince him to be a part of it?

Docherty: Well, thankfully he didn't ask too many questions. I mean the pitch was what I said to you. I wanted to make a film that speaks to the way games used to be made, for people who don't appreciate it. And I wanted to change the conversation about games.

As an ex-game dev myself, I'm increasingly watching more people treat games as unbelievably disposable. It's sort of offensive. And I wanted people to be aware that there were human beings behind these games. They're not just churned out automatically. I mean, you know, that's less and less the case now, of course [with AI], but the idea was to talk about game dev in the same way you would talk about novelists or musicians or actors or filmmakers or composers. And I think Jeff was definitely open to that idea.

I think that appeals to any creative person to be able to talk about the process, right? So it was a way to talk about something that we both enjoyed — classic arcade video game design — and his long career in the industry. Because there's something unique about somebody who's sustained a career for 40 years in game dev.

I mean Jeff still writes his own code. He has help with systems and stuff now — Giles is integral to Llamasoft, make no mistake. But it's Jeff's art, right? And it's a unique opportunity to show one artist's work from 1982 to now through the lens of video games. There are very few people in the industry you can do that with.

Time Extension: Besides Jeff, how did you go about tracking down people to interview for the film? How did these interviews wind up impacting the type of story you wanted to tell?

Docherty: It's interesting having this conversation with you when you haven't seen the film yet. Because the film ends up being about this intense relationship Jeff has with his audience.

So what I discovered was there was this group who call themselves "The Crew" (because, you know, they're 20-something guys who hung out a lot and did a lot of drinking). And out of these guys — Jeff and four other close friends — developed (for wont of a better word) Neon — an interactive light synth that ended up in the Xbox 360. And that's a story I originally came to through an interview with [the game developer] James Cope.

So, when I originally started the film, I wanted to do eight interviews minimum, right? Just to get the ball rolling and then raise funds off the back of that. I had some interviews lined up and Gary Liddon had introduced me to James and he was relating stories about something the crew had done — they called it the Alt Wallace Rave (it was really like a village fair that they just took over).

It was the first time that Jeff's wider community had seen the Lightsynth in action, so a bunch of people descended on this tent in the middle of a village, and just watched Jeff and The Crew doing this incredible light show to a really intense soundtrack. I didn't know I had a story until James Cope related this to me, and spoke about the emotional impact it had on him — I mean it was just like a profound evening for him. So I asked him about this community. And he told me about yakyak.org, which is like the message board where people have just gathered around Jeff.

Jeff is not a publicist; he doesn't need an entourage. But people just showed up and didn't leave. This yakyak message board was designed for like 50 people, but thousands of people ended up visiting it. It was about the time of AltaVista and people getting like always-on internet connection. So the first thing people would do was to search 'What happened to Jeff Minter?' And they'd type that into AltaVista — 'Where is Jeff Minter?' — and yakyak would show up.

So people were joining this message board and it became like this family. It was this group of people like-minded individuals who were all curious about what Jeff was up to. So the film's sort of about that, really, because that leads to a bunch of other interesting things.

A lot of people who loved Jeff, for example, became game developers themselves and would eventually rise through the ranks, ending up as commissioning executives for Sony, for example.

Shahid Ahmad was a commissioning executive at Sony, and he gave Jeff a couple of opportunities, and there was also Gary Liddon (who I've mentioned). He had worked with me on a budget game for Silverbird in the '80s but now he runs Rockstar Dundee.

So a lot of these people who were fans of Jeff back in the day rose to these positions of authority and would continue to offer Jeff opportunities where they could.

Time Extension: Through your access, did you ever get any special insights into any projects that never really saw the light of day? Like the GameCube title Unity, for example. Is there anything you can share about that project or others like it?

Docherty: The story of Unity is definitely a print-the-legend scenario and that's what I've stuck with.

Some details are just messy and inelegant. I remember seeing the demo video for that on YouTube — the horizontal Defender-style videos — I wanted that. But what's interesting is what emerged out of that was Neon, and that was an epiphany for me.

The story I thought that I would be telling was that this classic video game designer was being denied the opportunity to do these amazing games, right? But that is actually fairly rare when it comes to Jeff. The number of games that Jeff has failed to complete, it's like four maybe out of 120-something SKUs. Ut's nuts. So it's actually a rarity to talk about something that Jeff failed to do.

So I was drawn to the story of Unity. But really what Unity was (to go on a bit of a tangent) was Jeff realizing that you can't do next-gen console games by yourself. That was, in many ways, a turning point in Jeff's career, and precipitated Giles joining the team. So I went in to find out about Space Giraffe, I went in to find out about Unity, and what I ended up finding, was that Jeff just never stops.

There may be minor handicaps or hiccups along the way, and he doesn't earn much money that year. But the ideas in Unity end up surfacing in something else, like Polybius, for example. He's dogged in that regard.

He's wanted to make Space Giraffe 2 for decades, and it's happening. It's just he needs to pave the way to get there because the new version of Neon is going to be the background to that. He never lets an idea go and I respect the hell out of that. He's very economical, he doesn't waste anything.

Time Extension: That brings us up to our final question. For those who have already bought Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, do you have a succinct way to sum up the differences between that project and Heart of Neon?

Docherty: There probably is. I don't know if I have it. Digital Eclipse's Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story — Well, for one thing, it's only half of Jeff's story.

The goal of Digital Eclipse was to put you in the moment. It is to put all the games in your hands as accurately as they can, given that they're playable through emulators on modern platforms, right? So you get to play Abductor on a Switch. You get to play Llamazap on your Xbox One. It's unique and it's a huge challenge. And they did a lot of really incredible work to make that happen.

So it's a blow-by-blow, shopping list account of what Jeff did for the first 20 years of his career. That's what the Llamasoft: Jeff Minter Story is. What Heart of Neon is, is the story of an artist who happens to have video games as his medium of expression.

It's a film for people who don't play video games. It's a film about an artist and his audience. It's a film about fandom and passion and why everybody who plays games should give some respect to the classic arcade games.

There were some people I interviewed when the film was more historical kind of thing and those interviews have sort of fallen by the wayside because Heart of Neon was always intended to be a film for people who weren't gamers.

I would often say it as a joke — it was sort of true though — but with this film, I wanted my mom to know what I was doing with the Commodore 64 when I was 18, and what it means to be passionate about video games and want to make them yourself. And that was the story. So, the more in-depth historical details became less important. Most people don't need to know that Gary Penn was a journalist for Zzap64 and wrote this iffy review about Mama Llama. Here that is a waste of time, but that was perfect for Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story.

If you want to get your hands on the Blu-Ray for Heart of Neon, you can visit the crowdfunding campaign for the film here.