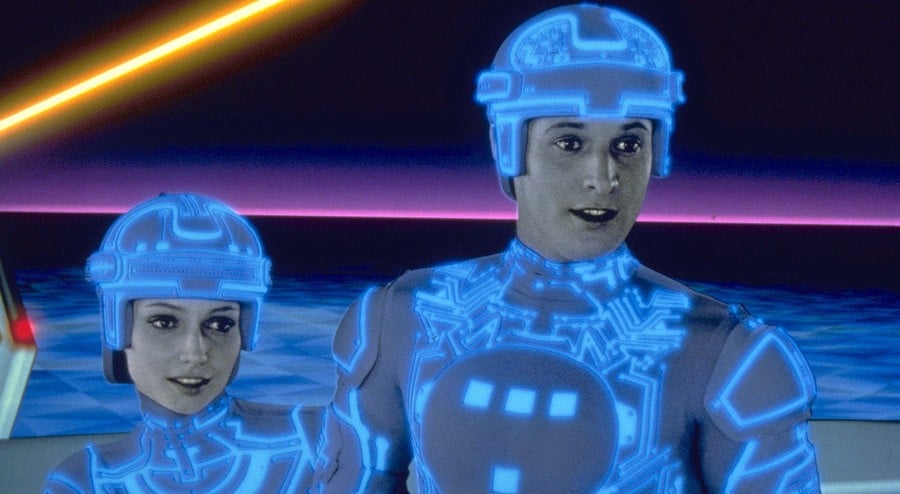

Many years before Disney decided to continue the Tron story on the big screen with Tron: Legacy in 2010, the Washington-based studio Monolith Productions collaborated with the House of Mouse on another direct sequel to the groundbreaking 1982 science fiction film, for PC (and later Xbox).

Tron 2.0, as the sequel was called, was a first-person continuation of the classic film's story, developed by a lot of the same team that had worked on Ice-T-led Sanity: Aiken's Artifact.

It followed a brand new character named Jet — the son of the former ENCOM programmer Alan Bradley (who was voiced here by a returning Bruce Boxleitner) — who one day inadvertently finds himself being digitised, kickstarting a chain of events that eventually sees him having to travel across cyberspace to save his dad and put a stop to the plans of an evil corporation named fCON.

Released in stores back in 2003, Tron 2.0 was launched to mostly positive reviews from critics, with Eurogamer's Martin Taylor, for instance, calling it "a grand achievement for Monolith", while PC Gamer's US Chuck Osborn described it "a refreshing alternative to the everyday war and zombie shooters" and "infinitely playable". In particular, many reviewers praised the game for its fantastic art direction, believing it to be a "visually spectacular" update on the original movie.

Earlier this year, while looking into the wider history of Monolith Productions, we spoke to a couple of individuals who worked on the video game sequel, hoping to uncover a bit more about the project. This includes the game's producer Garrett Price, the lead artist Matthew Allen, and the lead engineer Kevin Lambert.

They told us some interesting behind-the-scenes stories about the game, including how they were able to get the original Tron designer Syd Mead to come onboard, and how they ended up receiving a rather unexpected call from the agent of the French illustrator Jean Girard (AKA Mœbius) during the final days of production.

According to Allen, Tron 2.0 arrived at a time when the team behind Sanity and No One Lives Forever's PS2 was looking for the next project to work on.

At the time, the group had been developing various pitches for a bunch of licensed titles, ranging from Big Trouble In Little China to Dungeons & Dragons, when one day, pretty much out of the blue, a Disney producer ended up reaching out to the studio, offering them the chance to work on a new Tron game.

Garrett Price recalls, "It was Cliff Kamida at Buena Vista Games (a subsidiary of Disney) who basically said, 'We want to make a Tron game'. He said, 'We have this IP and we want you guys to do it.' And we were all super excited about what we could do, because it had just been that one movie and then the one arcade game. I remember thinking, 'Where can we go with this?'"

Allen, meanwhile, adds, "Disney really didn't have any internal publishing, but they liked Sanity, they really liked Shogo, and they really really liked No One Lives Forever. So they asked us. and we said, 'Sure!'. We had just done Aliens vs. Predator 2 and we basically told them that we were totally fine doing other people's IP.'"

As both Price and Allen remember, when the production team at Buena Vista Games reached out to them, they already settled on the idea of doing a sequel, as opposed to a retread of the film. Monolith's task was, therefore, to take this idea of creating a follow-up and to run with it, which meant coming up with a brand new story worth telling, and envisioning what the world of Tron might look like over 20 years after the events of the original.

For the former, the team enlisted the help of Marvel and DC comic book writer Steve Englehart (The Avengers, Captain America, Green Lantern) as a story consultant, who ended up working closely alongside the game's lead designer Frank Rooke to expand an initial outline the team had created. Meanwhile, for the latter, the Monolith art director Eric Kohler joined Allen in leading a group of other artists whose job it was to populate the world with new characters, FX, and environments.

"Frank Rooke was the game designer on Tron," Price tells Time Extension. "So he had a lot of influence over where we went with that. He had worked on No One Lives Forever — I think he was a level designer. But he had a bunch of ideas of where he wanted to go with it. But there was also Geoffrey Kaimmer [the senior world artist on the game] too, who was just an amazing artist, and he started doing some incredible concept art for where the Tron universe could go."

The design for Tron 2.0 was for it to be a first-person shooter, utlizing a modified version of the Lithtech 3.0 engine used for No One Lives Forever 2 (this would eventually be dubbed LithTech Triton). Rather than wielding a gun, players would start out the game with a light disc instead, with the option being available to access further upgrades as they progress, or unlock other Tron-like weapons called "Primitives", such as the rod, ball, and mesh.

Initially, I had hoped we could make the spiritual successor to the arcade game with the Recognizer flights and tank battles and the MCP cone. So I started cranking out ideas.

The basic levels in the game would see players making their way through the world, with the goal of completing various objectives and hitting specific story beats, with the team relishing the opportunity to work on such a beloved IP. There were some, though, who felt a bit disappointed to be working on another first person shooter - not least the engineer Kevin Lambert, who had originally envisioned making something more akin to the Bill Adams' classic Bally Midway arcade game.

"I was like a kid in a candy shop because I love Tron," says Lambert. "Initially, I had hoped we could make the spiritual successor to the arcade game with the Recognizer flights and tank battles and the MCP cone. So I started cranking out ideas. But when we sat down with Buena Vista they were like, 'Oh, we were thinking first-person shooter because we really like what you guys did with Shogo and No One Lives Forever'. That hit me really hard. But I was like, 'Can't we at least do the light cycles?' And they said, 'Of course, we can do the light cycles!'"

Unlike the rest of the game, the light cycle segments featured in the game contain a totally different perspective from the first-person action, with the camera instead sitting way back from the player to offer an angled view of the light cycle.

As with the original film, the goal for this section was still the exact same, with players having to eliminate their competition by placing a jet wall in their path, but Monolith decided to add a further layer of complexity, to the classic formula, introducing more elaborate map layouts and power-ups to "level up" the experience. Meanwhile, as for the light cycles themselves, the team decided not to reuse the original designs from the film, but instead got in touch with the original Tron designer and artist Syd Mead, who offered his services to create the next-generation of the futuristic bikes.

"We knew if we were going to level up Tron, the first thing we had to do was to get the look and feel," says Lambert. "So we had the engineering and our team trying to get that glow on everything. And that took a long time before it was really sick looking. But then when we started to think about the light cycles, somebody put us in touch with Syd Mead. We asked him, 'Can you make the next-generation light cycle?' And so he was drawing samples and we're like, 'Oh, they're like longer and cooler.'"

Speaking about the experience of working with Mead, Allen remembers, "Syd originally came up for just two days. On the first day, he gave a talk — he usually gave it at Art Center — about designing for Tron. Then on the second day we walked him through our technology and what we did because he was really interested in it and he's a really smart guy.

"When they told us, 'Hey, Syd Mead wants to come up and talk to you guys', both Kohler and I absolutely freaked out. We were a little bit bummed out at first when they told us he wanted to design the new light cycles, because we were like 'Oh, we wanted to do our own light cycles.' But then at the same time, we were like, 'Wait, no, Syd Mead's wants to design the light cycles for our game.' So he came up and he was just a wonderful guy."

While Disney would later "de-canonize" Tron 2.0 with the release of Tron Legacy, and has typically ignored its existence today, similar to other Monolith games from the past, the title still has its fans online, with players still competing online in the game's dedicated multiplayer mode and updating the game to run better on modern operating systems. In addition to this, it is also still available to buy digitally, with both Steam and GOG offering a cheap and easy way to pick up the game for PC.

I would have fucking slaughtered goats to make that shit happen. My first child would have been named Mœbius if that's what Mœbius wanted. I have every single thing Jean Giraud (Mœbius) has ever done. I have it in French, I have it in English.

Talking to those who were involved with the project, it's clear they still consider the project to be a dream come true, but that's not to say there weren't any regrets, with the most heartbreaking of these being a missed opportunity to work with the legendary comic artist and Tron concept designer Mœbius — something the team didn't even realize was a possibility until they were nearing the end of the project.

As Matthew Allen recalls, when the production on the game was coming to an end, they got a call out of nowhere from an agent representing Mœbius, who made it clear that the artist wasn't happy at being excluded from the project. For Allen, a huge Mœbius fan, it was a surreal moment, as he had never in his wildest dreams imagined that Mœbius might be interested in being involved. Yet, here he was getting yelled at on the behalf of his childhood hero, for not having the foresight to extend an invite.

As he explains to us, "If anyone of the people on that team knew that was even a possibility, I'm telling you, I would have fucking slaughtered goats to make that shit happen. My first child would have been named Mœbius if that's what Mœbius wanted. I have every single thing Jean Giraud (Mœbius) has ever done. I have it in French, I have it in English. I have the Métal Hurlant, and I have the Heavy Metal versions of it. Like he is the reason that comic books were a thing for me — outside of early Chris Claremont X-Men.

"Anyway, somehow we ended up talking to him for a bit and we did discuss some design decisions and things later on. But I fell on so many swords. I did that but ten times over, but the whole time I was just thinking 'I'm talking to to the greatest comic book artist who ever lived'. Then eventually, he was like, 'Okay, I get it. It wasn't you guys, you didn't know. But can I do some art for the project?' So he ended up doing this limited-edition lithograph of one of the characters Kohler designed coming through the computer, with a hand-pencil signature from Mœbius numbered by Mœbius.

"So I loved working on that game. I loved working on that IP but like that shit will never go away. That really scarred me for life."