There’s no shortage of arcades in Tokyo. Walk around any major shopping district, and you’ll undoubtedly bump into one of the chain arcades run by Bandai Namco or GiGO. Crane machines, photo booths, and modern arcade games fill these places, but Tokyo is also home to a number of retro game centres where you can play titles from the '80s and '90s. Japan’s history with arcade games started much earlier, however, and at Tokyo’s Dagashiya Game Museum, you can rediscover an oft-forgotten era of Japanese gaming.

Before Retro: The Games of Japan’s Candy Shops

“Dagashiya” refers to cheap candy stores that children would often visit to spend their meagre cash in the Showa era. Before convenience stores stood on every corner, these dagashiya candy shops served as a place where kids could enjoy some after-school hangout sessions.

Those without a sweet tooth had another reason to venture into these often cramped stores: arcade games. A far cry from the visceral action of Street Fighter II or even Pac-Man, most games housed in early dagashiya shops were pre-electronic, and those that did use electricity did not do much except flash some lights.

As video games rose to prominence, many of these games fell out of favour and shops were eager to dispose of them. Thankfully, the Dagashiya Game Museum preserves dozens of unique titles you won’t find in any traditional arcade, including games from major developers like Konami and Taito.

Dagashiya Game Museum: A One-of-a-Kind Gaming Experience

Software engineer Akihito Kishi opened the museum in 2009. Concerned about the games of his youth disappearing from the world, he set out to create a space for people to enjoy the types of machines often found in Showa-era candy stores. The museum is home to over two dozen games, with more in storage. It also rents out these retro machines for use in movies and television.

Located down a quiet red brick walking street in Itabashi and across from a shrine, the museum is not something you would likely stumble upon. The name of the museum is written with blank ink on wood right outside the door leading you to a treasure trove of unique oddities inside. Entry is only 300 yen, and with your ticket, you are given a cup filled with medals to use on some of the games.

A striking element about the museum is the sheer variety of different games. There are medal games which function like glorified slot machines, but others that resemble proto-pinball, games that have you navigate your ten yen coin around obstacles, some where you press a button to manipulate lights and more. Since you are given medals with your entry ticket, you’ll likely be drawn to the medal games first.

Medal games centre around placing a bet to win even more medals. 1977’s G. Circuit consists of a big electronic board where cars race via flashing lights. You can bet on which car gets first, second, and third, and nailing your prediction results in more medals. One of the more visually interesting medal games was 1988’s Kamesan Usagisan, a game where you simply pick who will win: the tortoise or the hare. Once you place your bet, the sign with the hare on one side and the tortoise on the other will rapidly spin, then come to an immediate halt once you pick the winner by pressing a button. A major appeal of these titles is the completely unusual and analogue features you wouldn’t find in a typical video game.

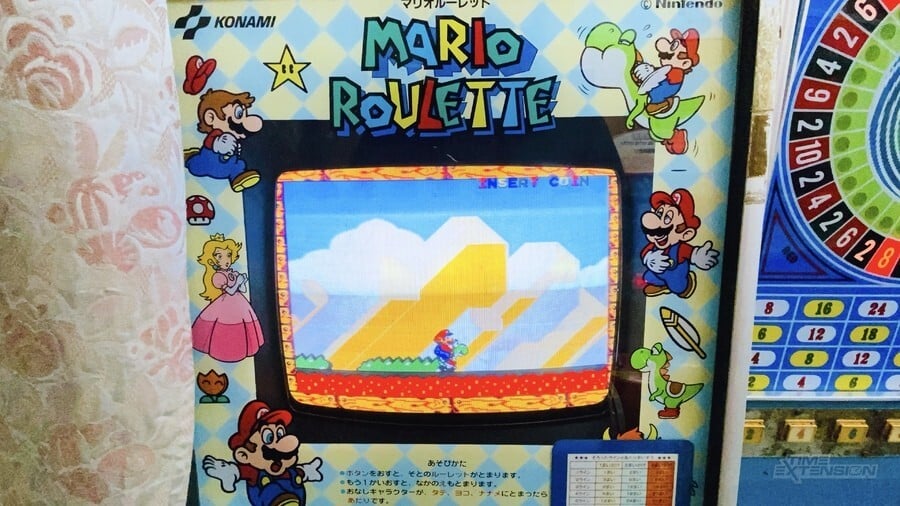

As a Nintendo fan, the title that immediately caught my eye was Mario Roulette. One of the museum’s more recent games, this 1991 title developed by Konami is a Super Mario World-themed slot machine. You try to match three power-ups in a row, not unlike a typical Toad House minigame. While the gameplay leaves a lot to be desired, seeing the Super Mario World graphics repurposed in a completely different game is an exciting find.

Astro Boy Rubs Shoulders With Gundam

Once you’ve run out of medals, you can use real money to play the museum’s other games. The majority of the machines only cost ten yen to play, with some of the more high-end ones costing thirty yen. You will bump into some machines with well-known IPs, such as Astro Boy, Disney, and Gundam.

The Gundam machine is particularly interesting as it was released in 1982 by Konami, predating most of their major franchises. The game resembles an electronic board game, where you race against an enemy Zaku to the end. Dice rolls are done via pressing the start and stop buttons, and depending on where the light lands, you or your opponent will advance.

Another game that relies on electronic lights was one of my personal favourites, Yama Nobori, or “Mountain Climbing.” Similar to Gundam’s board game layout, here you advance your climber by pressing a button. One press is one space. You need to dodge the obstacles indicated by flashing red lights to reach the top. Simple, yet exhilarating when you narrowly dodge a series of catastrophes like snakes and falling rocks. Since it completely relies on timing and speed, it feels a bit more fair compared to the others. An iconic game that appeared in countless candy shops from 1981, it was actually reissued in 2011 using LED lights.

There are many completely analogue machines that use springs and levers to control an object inside the cabinet. In Taito’s 1988 game Hoppu Poppu Goku, the ten yen coin you insert to play the game actually becomes your game piece. Using a lever, you navigate your coin across a series of obstacles by manipulating the platforms inside the machine. Using your own money as the protagonist of an adventure is a fun novelty, and skilled players will actually be able to get their coin back. If you are hankering for video games, the museum has Galaga in a customized, smaller cabinet that was common in candy shops.

Living up to the “dagashiya” in its name, you can buy snacks and soda at an affordable price. Patrons seem to save their money on games, however. On a weekend visit, the small museum had about a dozen or so vistors, proving that as long as people are putting in the effort to preserve games, the audience is there to play them.

While it may not be close to the typical tourist hot spots of Tokyo, Dagashiya Game Museum is a must for retro game enthusiasts due to its incredible diversity of games you won’t find anywhere else.

Tokyo Game Life is a Tokyo-based video game podcast focusing on Nintendo and gaming culture in Japan's capital. Tokyo Game Life is available on your favourite podcast app.