As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

"What everyone knows about Space Invaders and Pac-Man are all lies," says my source, on condition of anonymity. They add, "I don't want to be quoted. An interview can be full of lies; without reliable evidence, you cannot say it's true. They both say they invented their games from nothing, that it's a pure product of their ingenious minds. We know that's not true. Remember the pizza legend? Toru Iwatani says that he ate a pizza and saw Pac-Man. Impossible! The Pac-Man character already existed before he joined Namco, as a toy. And we know Pac-Man is a dot-eating maze game, which already existed – notably Head-On by Sega."

Pac-Man, released May 1980, is a cornerstone of video game history – to allege its creation story is a fabrication and that its claimed creator is taking credit for someone else's work, is a bold claim. But let's follow the evidence.

This is not the article I intended to write. It actually started with two contradictory sales numbers for old games, attained through oral interviews; wanting to ascertain which was accurate, I contacted a highly respected figure in the field of video game history. Said individual stated that neither number is accurate, and our discussion evolved into Pac-Man.

"Never trust creators, especially when they work for a company," says my anonymous source. "Iwatani has said off the record the pizza story is legend, but I don't have any proof he said this. I heard Namco wanted him to say the pizza story, and he stopped saying it after he left Namco, but never officially admitted it had been a lie. He would be in trouble with Namco. It's nice to read interviews and the stories they tell, but they are stories. Fact-checking is needed. Without facts, it's just statements, and precautions are needed when writing history. Because people love stories, so it will be endlessly copied and pasted everywhere until the truth is so tiny it's nowhere to be seen."

Well readers, all that's needed, then, is to find these truths and verify them. At least the dot-eating claim is easily checked. Head-On was developed by Lane Hauck and distributed by Gremlin / Sega, with multiple reliable sources citing a release date of mid-1979. The concept it originated, navigating a maze collecting dots, predates Pac-Man by around a year. The San Diego Reader even had an interview with Hauck in July 1982, where he stated: "Head-On just came to me. I just hashed on the idea of having fixed lanes all the way around the screen, and once you're in a lane, you're committed. Also, there were dots in the lanes, which bleeped and disappeared and added to your score every time you went over them. This was the world's first dot-eating-up game!"

Of course, mechanical concepts for games are a nebulous thing. Hardcore Gaming 101 wrote an insanely long thesis on fighting games that predate Street Fighter II – name-checking over 60 different titles in the process – showing that historically important games can justifiably stand atop a foundation of inspiration. So Head-On does not negate Iwatani's creativity, even though it was indeed first.

The allegation about the character already existing as a toy, however, is more troubling. The global phenomenon that is Pac-Man is as much about the adorable character itself as it is the game's mechanics - maybe even more so. As our source said, it would be bad for Namco if the legitimacy of Pac-Man's origin was threatened.

I actually met Toru Iwatani in 2016, in Leipzeig, at the Replaying Japan conference. I was giving an academic talk on the involvement of the yakuza in the history of Japanese games, titled Dark Side of the Sun. Iwatani was a keynote speaker, as was Masanobu Endou, creator of Xevious and The Tower of Druaga, and also Junko Ozawa, a long-time musician for Namco. As a group we all had lunch together, went sightseeing and conversed. I regret at the time not knowing about the contested origin of Pac-Man, since I would have asked them all directly.

I took photos and recorded Iwatani's keynote speech; the MP3 file runs to 1 hour and 4 minutes. At around the 4-minute mark, there is a discussion of the Pac-Man concept. Iwatani described how so many games then involved killing invaders from space, which appealed mostly to men. Pac-Man was the result of trying to make arcades more comfortable places for women and couples to go. Instead of starting with the concept of attacking, they started with the verb "to eat". He describes going through a dictionary and paying attention to the verbs, such as hug and push. Eating was seen as something couples did together in harmony. This leads to the pizza anecdote, and he reiterates the well-known legend of removing a single slice and seeing Pac-Man, along with the now famous photograph of him. The only hint of this story being manufactured or staged is a throwaway line: "That was actually a picture taken by a journalist." After this, he describes the cuteness of the ghosts, comparing their relationship to Pac-Man as being akin to Tom & Jerry.

At the end were questions from the audience. Sadly I did not use this opportunity to ask about Pac-Man's design. No one asked about it in the Q&A session. However, I interviewed Professor Yoshihiro Kishimoto in September 2013, for The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. Kishimoto is another former Namco employee and programmer on Pac-Land. He doesn't specifically mention the origin of Pac-Man's design, but his interview corroborates a key point.

"The names of people on development teams were kept secret by the company so they wouldn't be lured away by competitors," explained Kishimoto. "When I joined the company my supervisor told me it was a company secret as to who was working on which games. In Japan, there are many things that I cannot say in public. This is one of the reasons for my agreeing to your interview. This would not be accepted by Namco for publication in a Japanese book. They would say you have to take that out. So I want to document it for the record, for future generations."

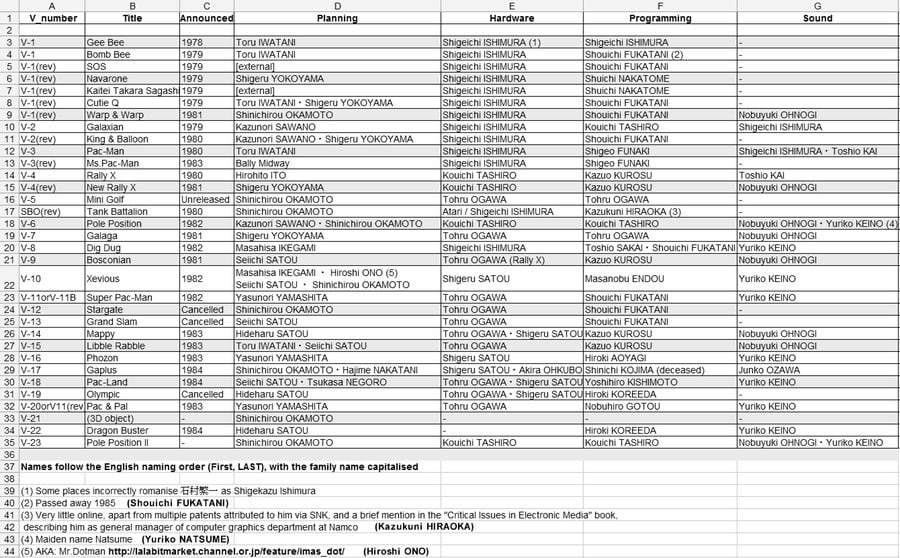

Kishimoto then handed me a secret document listing Namco's arcade games from 1978 to 1984, and all of the staff who worked on them. Pac-Man is listed in 1980, with planning by Toru Iwatani, arcade hardware by Shigeichi Ishimura, programming by Shigeo Funaki, with sound by both Shigeichi Ishimura and Toshio Kai. There are 33 titles listed, and for all of them, Namco wanted the creators hidden. Staff have spoken about their work after leaving the company, but even then there are limits on what they can say.

It's not just psychological intimidation either, Japanese law does not allow for free speech or freedom of the press. Every screenshot in Famitsu needs official approval from a publisher. If a book is published in Japan without permission, game publishers have legal recourse to have it prohibited from sale. Florent Gorges' book on Space Invaders was allegedly removed from Japanese shelves after a week because it did not have prior approval. [We reached out to Florent but he was unavailable for comment prior to publishing.] As Kishimoto confided, "There are ways of documenting game development. One is to have it published by an overseas publisher, which will not be subject to checking by Japanese companies."

Given these facts, it's unsurprising that Toru Iwatani would be reluctant to rock the boat. Namco has the ability, in Japan, to shut down all discussion. And this, readers, is where the investigation gets real weird, real fast.

In December 2020, roughly four years after I'd met Toru Iwatani, researcher Kate Willaert dug up and posted a megaton of information on Twitter, with photos. Starting in 1974 with Tomy's "pakkuman" coin bank toy, she traces the iconic character through various other toys over the years, including one rebranded as Mr Mouth for the USA. Kate then shows how much later - after some licensing chicanery between Tomy and Namco - these toys were rebranded officially as Pac-Man products.

The photos do not lie. The iconic character design of Pac-Man was well established before the game came out, and there is ample photographic proof. This would be the smoking gun in the investigation, except things get even more bizarre when Kate links to a 1984 court deposition.

Dated 27 January 1984, the court documents detail a battle between the plaintiffs Midway and various defendants, including North American Philips Consumer Electronics Corp, who "contend that Pac-Man is not an original work of authorship." What's fascinating is that on pages 23 and 24 of this document are statements directly from Toru Iwatani.

Toru Iwatani is asked specifically if he was aware of Tomy's earlier coin-bank toy, which had the exact same name, Pac-Man or "pakkuman".

Question: Have you ever seen the Tomy toy called Pac-Man?

Answer: Yes, I have seen that.

Question: Did you see the Tomy Pac-Man toy [...] before you developed the game idea for Namco's Pac-Man?Answer: No, I think it was after.

Question: Then my question, Mr. Iwatani, did you in any manner base your Pac-Man character for the Namco arcade game on the Tomy Pac-Man toy?

Answer: No.

An entire court case was fought around the opening statement of this article nearly 40 years ago. Yet despite the millions of words written about Pac-Man since then, it's seemingly never brought up. The legal jargon is pretty thick in the court documents, but it appears the judge did not grant summary judgement in favour of the defendants. The documents are a matter of public record and can be viewed by anyone.

Even though the judge did not find in favour of the defendants, it's important to understand that under copyright law the defendants had the burden of overcoming the presumption of validity. Think of it as being similar to "the presumption of innocence until proven guilty" in criminal law. Also, keep in mind this was 1984 - they did not have the luxury of digital phone cameras, social media, or even the internet as we know it.

Regardless of the court verdict, the evidence Kate dug up is compelling. Before the 1980 release of the Namco arcade game Pac-Man, there absolutely was a Tomy manufactured toy that looked identical to Pac-Man and had the same name. Much later Tomy and Namco came to a licensing agreement.

Was the design of Pac-Man plagiarised? We may never know, unless its true creator comes forth and is free to speak openly. Does it really matter? It certainly doesn't diminish the incredible impact of Iwatani's creation; Pac-Man remains a fantastic video game and one which came at just the right time, and Iwatani deserves all the credit for dreaming up such a compelling arcade game. But the pizza story everyone loves to quote endlessly? Perhaps that's not so true after all.

John Szczepaniak has been a journalist for over 15 years and has written for more than 20 publications, including Retro Gamer, GamesTM, Official PSM, Game Developer, and Gamasutra. He is the author of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers series of books.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.

Comments 4

Wow!

I am usually skeptical of "Word vs. Word" Debates. But this one shows good research and really makes you think.

This is extremely important. I hope your future book(s) will continue to shed light on the poorly-documented early history of gaming!

That is pretty intense. Especially all of the secrets about the dev teams.

I had that Tomy Pac-Man game, but (dont know if this was a localisation thing to the UK) it was called Munchman and released by Grandstand, I even remember the theme tune before you started playing

I even remember the theme tune before you started playing

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...