On 21st February 1993, Nintendo and Argonaut Software released the space-action shooter game Star Fox for the Super Nintendo in Japan. An unlikely collaboration between two companies on opposite ends of the globe, it was a smash hit and has since spawned a number of sequels and remakes such as Star Fox 64, Star Fox Assault, and Star Fox Zero.

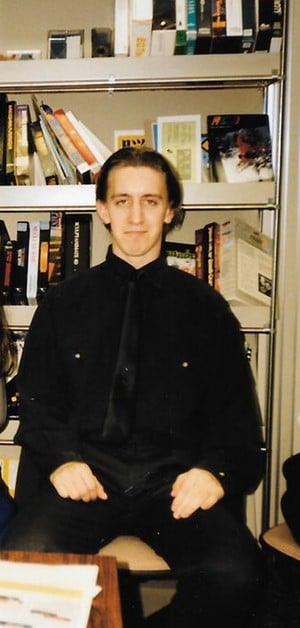

Ahead of its 30th anniversary, we were fortunate enough to sit down on a call with the original programmer on Star Fox Dylan Cuthbert to talk about his experience of working on the series. Cuthbert not only worked on the original Star Fox and its sequel Star Fox 2 in the early-to-mid 90s but also returned to the series as the director of Star Fox Command and Star Fox 64 3D in the 2000s at his new company Q-Games. Some of the topics we covered in our conversation include how he got his start at the British developer Argonaut, working with Star Fox's mysterious composer Hajime Hirasawa who quit the games industry shortly after the game's release, and where he thinks the series should go next. What follows is that conversation, but edited and condensed for clarity.

Time Extension: To begin, let's go all the way back to you joining Argonaut. I'm wondering, how did you get involved with the company in the beginning? And what was the company like at the time?

Dylan Cuthbert: So I think I saw an advert in [Popular] Computer Weekly or something like that. It was like a tiny, little advert in it and I applied and I went along and it was basically just a house. Like a semi-detached house in [Mill Way, London]. I rang the doorbell, went into the hallway of this house, and sat down on like a regular couch in the living room, like a settee. It looked like someone's living room, honestly. So, you know, that kind of set the tone for that.

I didn't get the job in that interview. I got the job probably about two months later because I didn't have any 3D demos at that point. I went home and did some 3D demos on the Amiga and I sent those in, and then they phoned me up the next day and gave me a job.

When I started there, they put me in a second-floor bedroom with one other guy. There were no beds, of course. But it was one other guy who was also a programmer and we basically just got on with making Starglider 2 for the PC at that point. It was just like working at home really because it was just a whole house. It had a kitchen, you know, it had the standard like toilet underneath the staircase kind of thing. And there was a garden outside that I never saw anyone venture out into.

Eventually, after about a few months, there was like a renovated sort of attic, which also had a bathroom as well, right on the top floor and I basically wrangled it so I'd be up there where it was a bit quieter and a bit more pleasant. It gave me a lot of time to concentrate on stuff.

Time Extension: Cool! And like, how quickly did Argonaut grow, I guess, pre-Starfox? Had it gotten like an office by the point where it was communicating with Nintendo? Or was it still fairly small?

Dylan Cuthbert: I think they moved out of the house after about maybe a year and a half into a pretty grotty office in Edgware on the other side of town. I don't remember it being very nice, but it was actually a proper office. And we were probably there for a couple of years before we moved again to an office in Colindale. We were like moving slowly towards the center of London, I suppose.

That was like an old warehouse, which had been converted into offices. So, we slowly upgraded over time. Before they moved into that Edgware office, I think they had grown to like 12 people and for a semi-detached house, that was just a bit too many people, and that's why they moved. And then the Colindale office, I would say there were about 20 people. Maybe a bit more, but not much more. And that was about the time just before Star Fox was in production, I think. So I was making X at the time for Game Boy. So it grew. And then after that, of course, it grew a lot quicker with like the chip stuff and just the money coming in from the FX chip as well.

Time Extension: It'd be interesting to hear, were you aware of any of the other British companies working with Nintendo at the time like Rare and Software Creations?

Dylan Cuthbert: Um, not really. I mean, I obviously knew Rare as Ultimate Play The Game back then. And, by the time we were doing Star Fox, they'd become Rare, but they hadn't really released that many games at that point, on the Super Nintendo at least.

I do remember Jez [San] was very connected because there was an agent called Jacqui Lyons. She was an agent that represented a lot of people, including, I think, David Braben even. So she kind of represented all these like British game devs at the time basically as an early form of an agent. But that was all sort of on Jez's level, so she'd have her clients and they'd all kind of know each other. So, we didn't really get to meet too many of them or know much about what was going on because there was no internet, obviously, so there was no way to like connect with these other people.

I do remember Peter Molyneux popping around one day because he was in the middle of the game that came after Populous. It was a 3D thing, very similar to Populous, but using actual 3D polygons and stuff, and he came around to Argonaut to talk to Jez and how to optimize 3D on it. That was about the extent of it. There were a couple of other people on the fringes here and there, but you didn't really get to talk to any of these other developers. There was just no way to find them. So yeah, it's weird, we were all kind of insulated, really.

Time Extension: That must have made the circumstances around Argonaut's close partnership with Nintendo even stranger then? Like, do you remember how it specifically came about that you were personally wanted inside Nintendo's offices for Star Fox's development?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, basically, it was because we were knocking up demos on stuff. I'd made a 3D demo on the Game Boy by hacking it and one of the other guys had made a 3D demo on the NES.

We didn't have access to [dev kits] and we didn't even know about the Super Nintendo at that point. So, Jez was basically, showing the demos off at CES in America when one of the younger guys at Nintendo of America, Tony Harman, saw them and realized how different they were from everything else Nintendo was doing. And also, you know, 3D was kind of like very novel at the time. He basically pushed everything through and hooked everybody up and then Jez came back from that show and just basically said, 'Yeah, in two weeks, you're flying to Japan to speak to Nintendo', and then that was kind of the beginning of it, really.

We went over to Japan and the people who actually made the Game Boy like [Gunpei] Yokoi, and [Takehiro] Izushi and people like that just said they were amazed that there was 3D running on the thing. They'd only imagined sprites and a few scrolling backgrounds.

Back then, [the demo that became] X was already signed to a company called Mindscape, but Nintendo bought the rights from them. And then at the same time, we also started the FX chips stuff as well, because in the same meeting, Nintendo had told us that they wanted to do 3D on this new machine they have, and that was the Super Nintendo.

They showed us a prototype of that with a very early version of Super Mario World running on it and an almost finished version of Pilotwings. Miyamoto said, 'We want to be able to render this plane in polygons because it's taking too much time and effort to draw all the frames'. They couldn't get all the angles, so they wanted the plane to go all over the place and they couldn't do it.

Pilotwings didn't get the FX chip obviously, because that was already like a launch title, but it kicked off that conversation. And then because Argonaut had been involved with the Konix Multisystem, which was an interesting console that didn't come out, we knew the people that made the special custom chips and Jez was able to call them directly from that meeting in Japan.

There was a phone in the corner of the room and he called Ben Cheese, one of the chip designers on the Konix, and said, 'We've got this cartridge. Here's the pin layout, this is the information we've got, can you put a chip on it?.' And of course, Ben was just out of a job, so he's like, 'Yeah, we can do it'. Very gung ho. So, Nintendo signed it up and basically started doing the contract negotiations and working with Argonaut and Ben on the chip design.

Time Extension: After X, when you traveled from the UK to Kyoto, Japan to begin work on Star Fox, did you have to adjust to the differences in the gaming culture? And did you spend any time trying to familiarise yourself with the popular Japanese computers of the day?

Dylan Cuthbert: Not really. So, the main aspect that I sort of got into was basically the arcades, really. I think, back then, at least, the computer culture was very geeky, even more so than in the UK. In the UK, it was more hobbyist. You know, the Spectrum, Commodore 64, and Amiga, and all that, was very hobbyist. And it was kind of hobbyist here too, but in a much geekier way, I think. There weren't many people at Nintendo who had any kind of home computers really at the time. And so, there was a lack of that, really. I think that might be why we were more advanced on the programming side [than Nintendo], because, you know, we'd all grown up with that stuff and they hadn't really.

Of course, they did have them. And I'd seen magazines and adverts for various machines that don't exist anymore that were similar to machines we had, but they were all very expensive. And I think the consoles came out just a bit too early [in Japan], so they just switched over to those before they even started trying to program their own games and stuff.

We didn't really have a console kind of thing in the UK. And the Famicom and the Super Famicom, the games were just so good on them. The Famicom especially, you know, the games were just so good at the time compared to any of the games we had on like the Spectrum. So I think people just got a bit complacent with that. So the biggest thing really was the arcades. The arcades were amazing here, compared to the UK, and the choice and the types of games and everything were just so much better, so part of that climatization was basically in the arcades.

Time Extension: A lot of people today point to some very obvious kind of references in terms of Star Fox: things like Argonaut's earlier game Starglider and the film Star Wars, for example. But were there any kind of more obscure influences from the things that you were playing in the arcades in Japan?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, I mean, the biggest influence, which is still really obvious, is Starblade from Namco. We took a lot of ideas and pointers from that game.

There are some sections in Star Fox that are quite heavily influenced by that game, but that game is like a fixed path. You don't really fly around in it. You just go through a fixed path and then you shoot at things on your way through. But the 3D was pretty impressive, and the sound design was as well. And there are a few interesting things in the way they'd done the shooting part of the game that we kind of picked up on and then expanded even further in Star Fox, I think.

There are other games too, of course. There was another 3D game after Starblade, called Solvalou, which is based on the old 2D shoot 'em up Xevious. So, it was a sort of 3D sort of Xevious game. That was really hard — they did a bad job on the difficulty tuning on that game — but the soundtrack on that and the 3D, at the time, felt really, really good. We didn't really take too much from that, but there were some ideas [here and there]. Like if you play both of those games, and play the original Star Wars Arcade game, there are little bits borrowed from those three basically.

Time Extension: Online there are a lot of people curious about Hajime Hirasawa, the original composer on Star Fox. He worked on Star Fox and a few other Japan-exclusive Nintendo games like Time Twist, and then sort of disappeared from the industry. Do you remember much about the collaboration with him on the music? Because today, that music is so iconic. The starting music, in particular, is still possibly one of the greatest intros or first-stage themes in any Nintendo game.

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, the end credits were really amazing as well, like the soundtrack on the end credits is, I think, really, really cool. But yeah, Hirasawa was a really nice friendly chap. I was quite sad, because when we came back to do Star Fox 2 he had already quit, so I didn't know at that point that Star Fox was [going to be] his last title. I don't know what titles he did before, but you mentioned that, yeah, you found a couple.

He was fairly young, I think, at the time. I think he was like 26 or 27, maybe a bit older, and he was just really friendly. I got on very well with him because I've always liked synthesizers and music, so, you know, we'd always talk about that kind of thing.

He even gave me — I've lost it — but he gave me at the time a CD of more orchestral versions of the Star Fox music. This is like 1992, so it was probably a tape. And that was really cool. He'd actually gone through and remade all the music and redone it all, and he wanted to release it. I think the main bone of contention with Nintendo maybe was that he wanted to release it under his own name and get some money rather than go through them. Then I think they had a falling out.

Time Extension: Yeah, from what I've seen, it seems like the main point of contention was the ownership of his music and the rights of being able to release it. I think you may have said this before, but didn't he later end up working on the MIDI format in mobile phones?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, so he left and started his own company, and eventually, he patented the format for "Chaku-Mero", meaning the little jingles that old phones used to play to copy normal music or whatever.

He created a very, very compact, advanced sort of MIDI format to record these little jingles. So you could actually download your favorite song as the ringtone. So that technology was patented and it ended up that that is the same technology that everybody used worldwide, so he got a lot of money from that. So he's quite a good businessman.

That's probably why he was kicking up this fuss about the soundtrack on Star Fox because he knew that there was probably a bit of money to be had, and he wanted to be more independent and do that. So he started that company and basically made a fortune off that patent. His office, I think, is still only down the road from Q-Games. It's like three doors down.

Time Extension: Oh, cool. The company is called Faith, Inc, isn't it?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, Faith.

Time Extension: Besides the game's music, another aspect that Nintendo was responsible for was the character designs. Do you remember when the Star Fox team was added? And what was in the game beforehand? Were there just no character portraits at all?

Dylan Cuthbert: It's a good question. I just remember it came in all of a sudden. It was definitely later on. I think like three or four months before the game shipped, they asked us to create this like text system to display the messages and stuff like that, and then they wanted like a little area to put graphics in to say who was speaking. I think we put some dummy graphics in there, to begin with, but I can't remember what they were now. Then all of a sudden, the artist, [Takaya] Imamura just went away and just started drawing all these characters.

They all went into the game in one go, because it was a graphics bank. Then the planners on the game, the game directors, I suppose, [Katusya] Eguchi and [Yoichi] Yamada, just beavered away, putting them all in the right places around the game. So it kind of went in very quickly, I think. Probably within two or three weeks.

In fact, I remember us sending a version back to Argonaut for them to test, and we'd been like busy like building bosses and stuff like that, or like optimizing, and they came back and said, 'You know, the game's completely changed. It's actually really good!' (Laughs). So, the game really just clicked into place. Even Argonaut was surprised. I do remember that reaction.

Time Extension: It definitely made it appeal to a younger age group. I know I played it when I was very young, for instance. I feel like, if it didn't have those mascot-style characters, it would have been hard for me personally to connect with it. I think that's kind of what was so genius about them is that it just kind of brought that whole other element to it.

Dylan Cuthbert: It made it very Nintendo, didn't it? Whereas, until then, it had been very British in a way. Like it was a bit colder, harsher, and dystopic. And all those things we kind of drew from [classic] British sci-fi. And Nintendo was saying, 'Nope, we're not having any of that, we're going to make it a bit cuter and fluffier and cartoon-like,' and they just kind of went to town on it. I [also] heard that Miyamoto liked Thunderbirds a lot.

Of course, Thunderbirds is pretty stark as well, but it's also kind of funny in places. He kind of took the idea of that kind of miniature puppet look and then he decided to make it more anthropomorphic to make it appeal more to a Japanese audience. Because he realized that the 3D, as it was, would be too much for the regular Nintendo audience who are used to Mario and cute characters. And he realized that he couldn't just put out a hardcore sci-fi kind of 3D game, even if he wanted to, because at that point, at least, the market wasn't ready for it.

So, I think, quite strategically, you know, they said, 'Okay, let's Nintendo-ify this game now we've got all the basic elements in place, and let's create a balance to this sort of harsh, polygonal kind of look'.

Time Extension: Yeah, I'm wondering, after finishing Star Fox 2, you decided to leave Argonaut for Sony. Why did you decide to make that decision?

Dylan Cuthbert: Basically the PlayStation came out while I was making Star Fox 2. And I was a big fan of Namco at the time. I even emailed someone on their server in Japan to try and get a job, but they didn't respond. Anyway, I really liked Namco, and they had Ridge Racer on the PlayStation, and I thought, 'Wow, this is really good'. It made me want to work on the PlayStation. So, you know, it was a combination of Ridge Racer and the PlayStation as well. And so, I tried emailing Namco, but they didn't respond. And then on Usenet, if you can remember Usenet, someone posted from PlayStation in America where they were just starting out.

I don't think the PlayStation 1 had even come out there yet — they were just preparing for it — and they were asking for engineers and programmers. So, I emailed that guy, and he said, 'Okay, where are you now?' I said, 'I'm actually in the Nintendo offices right now working on a title.' I was like, 'A year or two ago, I just finished Star Fox, and that was quite a big hit.' And then he goes, 'Oh, all right, yeah, okay, let's set up an interview.' So, we set up that.

Then when Star Fox 2 finished, and I flew back to the UK, I stayed at Argonaut for a few months, and then did the interview and got the job over at PlayStation. I got to work on their 3D hardware, which was a lot of fun.

Time Extension: After five years at Sony, you returned to Kyoto to set up your own studio, Q-Games. Just how important was the GBA game DigiDrive for getting you back in the door with Nintendo?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, so we pitched a couple of games, one of which was DigiDrive. And there was another game as well, which didn't see the light of day. It was based on that gyro thing that Nintendo put out eventually on the Game Boy. We made this game and we'd imagined that maybe a gyro could be put into the cartridge. And so we took that along. It surprised Miyamoto, I think, so he signed up both games to be prototyped. But eventually, he just chose one of them and that was DigiDrive.

Nintendo pushed it to be released as part of the Bit-Generation series for the Game Boy Advance. It wasn't originally developed as that. It was originally developed as a standalone Game Boy game as part of these two experiments that we were doing. But, you know, It was really good getting friendly with Nintendo again, and meeting all my old mates there. It kind of opened the door for Star Fox Command, Star Fox 3DS, and all the DSI titles we made as well.

Time Extension: Yeah, I guess, like, in terms of Star Fox Command, do you remember the exact moment where that came up in conversation with Nintendo in terms of you going back to create something in that world again?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, I can't remember exactly when it was, but it was probably around the time that we were showing DigiDrive. We'd gone to have a meeting with Miyamoto, and he just said, 'Oh, we need someone to make Star Fox for the Nintendo DS and we thought maybe you could do it.' Something along those lines.

They wanted someone to bring in the ideas that they had for Star Fox 2, and blend them in with the original Star Fox. So they wanted to do something a bit more experimental. And they kind of appreciated the fact that Star Fox 2 is very experimental, and we were trying out all kinds of stuff for that. They wanted to do something similar for Star Fox Command, where it wasn't just like, you know, a port of the original version or a port of the 64 version. They actually wanted something new and different. That was our kind of mission, I suppose, and that's the mission we were given.

So, we knocked up a demo in three months, which was basically similar to the original Star Fox, in a way; it was like a sort of on-rails thing where you're on this space elevator hurtling down towards the ground, and then all the elements of Star Fox are kind of happening on the elevator. You know, like enemies and lots of weird creatures are coming up, and then you go into like a tunnel at the end and you'd be shooting stuff there as well. It's actually a really cool demo. And that was when Miyamoto said, 'Okay, yeah, this is okay, this is good, but we really want you to push it even further and do something even more different than this. We don't want to just copy the original Star Fox."

So, we just went to town on it and we worked with Imamura-san, who is the producer of Star Fox 64 and also Star Fox Assault as well.

Time Extension: Star Fox Command has kind of taken on a bit of a divisive reputation in recent years. I'm wondering, how are your feelings on it looking back? Do you feel like there are any big regrets? Or do you feel you pretty much did as you intended? You kind of did something different with the property and kind of, yeah, went in a more experimental direction?

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, that was [really] the thing. Miyamoto didn't want the same thing again, and I'm always into experimental ideas as well, so we just basically took it in an experimental direction. I mean, it's one of my favourite games in the series, because it's a little bit different.

It's also handheld as well, right? So, we couldn't do like long play sessions. That's part of the reason why we kind of made it more sort of episodic as you go through. The only thing really that I wish we had more time for was I wanted to have a few more battle types. I wanted to have an on-rail sequence of battles as well. You know, the encounter battles that you have, they're always sort of all-range in the current version, and I wanted to have some which were on rails as well, but we didn't have the time to do that. It couldn't be helped, and also, we probably didn't really have the ROM size to do it as well. You have to remember, these are all running as ROM cartridges, and so there are size limitations as well coming into play; we couldn't just put everything in there.

But I think the game has a lot of very original ideas in it, and one bit that I really like about it is that it lets you play or roleplay the other characters in the series, right? So, you know, you can become like Leon or you can become like Katt. You know, there are all these sub-characters that you get to play. You get to fly in their ships as well, depending on the story that you choose as you go through. And of course, the story format as well, you know, is based on the sort of the choose your own adventure kind of storybook format, where you make choices and you kind of go through and do stuff, but it's designed to be played over and over again in fairly short sessions, and so that's part of the game design we had to work with because it's a DS, you know.

The battery life on the DS when it first launched wasn't amazing. I mean, I think it was like three and a half hours. It wasn't very long on the very first version. Also, the screen wasn't backlit so it would strain your eyes as well. So we had to work within these kinds of limits at the start because Nintendo was very worried, you know, about showing those limits.

Time Extension: Yeah, I mean, that was the era of Nintendo warning users pretty much every half hour to sort of like take a break from gaming, which is, I guess, why so many of their titles at the time were broken down into those bite-sized experiences.

Dylan Cuthbert: Yeah, we basically just tried to put as many rich ideas in there as possible, like within those bite-sized experiences. So it was a little bit of a departure from like, say, Star Fox Assault, which is more of like a full-on action game. It's a great game, but it's mostly action — it's a bit more like the original Starblade in that sense. And so, Star Fox Command is a little bit quirkier in a way and it's much more tuned to be a handheld game in that sense. And I like controlling with the stylus, because it was a lot of fun doing the spinning controls for the Arwing and stuff like that. Also, you can play with the voices! You can record your own little weird little snipped up voices into the game and have yourself speaking back to you in a way. You can use rude words for that as well. So, that's always fun.

Time Extension: Just as one last question, and I guess this is probably the question that you'll be asked the most, what do you think the series should do next? Should it go down a more traditional route or continue to be a series where developers are encouraged to innovate and experiment?

Dylan Cuthbert: There's a lot of ways to approach it, but like, visually, I think it should move more towards the sort of miniature model side of things, where it looks like, you know, the Thunderbirds in a sense. I think visually those are the real roots of the series because that's what Miyamoto envisioned at the start.

Then on the gameplay side, obviously, it should be, you know, cinematic and epic in a way, with very strong set pieces and that sort of adventure feeling as you go through. I would also probably play a lot more with the characters, you know. Just really expand their interactions and that side of things.

It's not really my place of say, you know, but the best advice I could probably give Nintendo is that they should just basically assign like 10 or maybe 15 people who are very passionate about it, and then just let them run with it for like a few years and do nothing but that. Not aiming to, like, get a game out — obviously, a game will come out eventually — but just building up that universe again, you know, and getting back to basics. Because the original Star Fox had a lot of that sort of British 3D gaming side in it, from me and Giles and Krister [Wombell], and slowly that kind of got erased.

Star Fox Command came back in and brought a little bit of that back in, but even Star Fox 64, you know, kind of lost a little bit that the sort of British subtle charm in there, and that sort of Thunderbirds side. I think if it was going to be rebooted or remade, I would personally concentrate on that side of things first, trying to get the charm back in, which is really one of the key things I really liked about the game originally as well.