Over the decades, there have been countless video games based on the popular children's doll Barbie, from point-and-click detective titles to action platformers, but it all started with a single game for the Commodore 64 — 1984's Barbie.

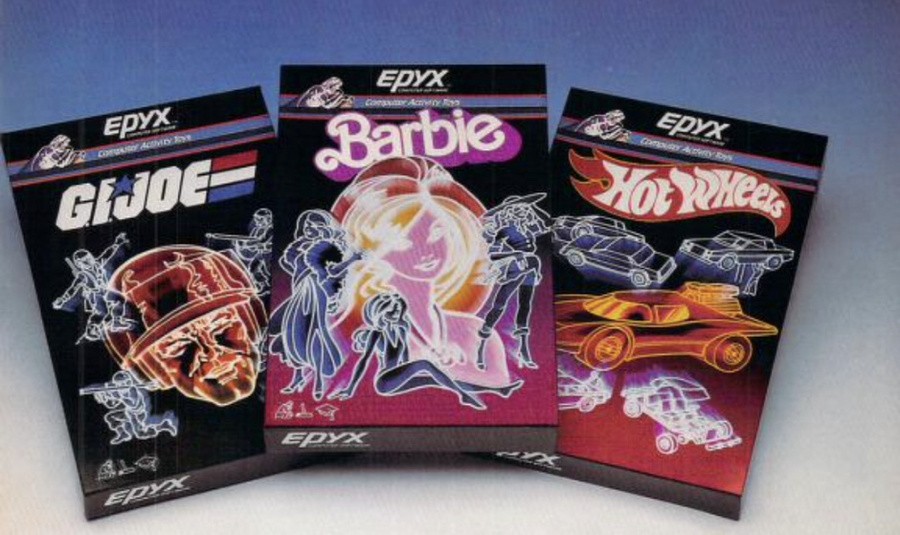

Developed by the Chicago company A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates and published by the San Francisco-based Epyx, it was included in a range of "Computer Activity Toys" alongside other titles based on Hot Wheels and G.I. Joe. Barbie, like the other games included in this range, was designed to be non-structured and non-competitive in nature, with the software meant to act as a springboard for the player's imagination, rather than being centered on winning and losing.

Epyx hoped that this virtual version of the doll would be a hit upon release, but the game was only modestly successful, suffering from a lack of marketing support and awareness among consumers. As such, it's been somewhat overlooked by video game historians, even in spite of the tremendously influential multimedia franchise that has followed in the decades since. So, with Greta Gerwig's star-studded Barbie film set to launch later this year, we thought what better time to investigate the doll's obscure entry into the world of video games.

Over the last few months, we tracked down Epyx's former president Michael Katz, the former head of Goldfarb & Associates Eddy Goldfarb, and Barbie's programmer Larry Irvin who were all able to fill us in on the incredible story behind the doll's first foray into games. But first, we should probably take a little look back at the history of the doll itself.

Video Games, A New Frontier

In 1959, the toy company Mattel released the first-ever Barbie. Created by Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler, it was based on the German fashion doll Bild Lilli and was styled in a zebra-striped swimsuit with a choice of either blonde or brunette hair. What was remarkable about Barbie for the time, and something that was key to its initial success, was that in contrast to the majority of toys available for girls, it was an older doll and wasn't necessarily aimed at teaching children how to become good mothers. Instead, it was an outlet for a child's creativity and imagination, giving kids the opportunity to personalize their doll based on their own tastes and interests.

This approach proved to be a hit with young girls, and as a result, Barbie quickly became an important part of Mattel's business. This inevitably led to the release of even more dolls as well as new accessories and playsets. By the mid-80s, Barbie was a pop-culture phenomenon, appearing across board games, picture books, and novelty records. But there was still one area where Mattel hadn't yet taken advantage of her appeal: video games.

Mattel was obviously no stranger to video games, having created one of the world's first all-electronic handheld games with Auto Race, and released the home console, the Intellivision, in the late '70s. However, after the North American console market crash of '83, the company found itself pulling out of games, leaving the door open for potential licensees to obtain the rights to some of its more famous properties.

Among those interested was Michael Katz, a former Mattel marketing director, who had recently taken over as the president of the San Francisco publisher Epyx.

"[Mattel wasn't] in computer games/software at all," Katz tells us. "Intellivision was dead and video games were taking a rest. The lull wasn’t as much from bad new game releases...the category had reached temporary saturation. ‘Enter computer games for C64, Apple, IBM for a different, ‘more sophisticated audience."

Katz saw the opportunity to create a new line of games for the home computer market, which would be based on pre-existing toy brands. So, he reached out to his contacts at Mattel, Rita Fyre and Mike Lyden to acquire the computer rights to Barbie and Hot Wheels.

The former Epyx president Michael Katz explained his thought process to Time Extension in January of this year:

"We wanted to expand the genres of software into the most popular selling categories. One of the categories that we had when I was in the toy industry was ‘Activity Toys’. Not games, but Activity Toys. Activity Toys were basically playing an activity with no win or lose criteria, which would make it into a game, but it was an activity just like playing with toy soldiers or playing with dolls. My concept was we wanted to have an activity toy category, we wanted to have something involving dolls, and we wanted to have something involving soldiers because toys and games are real-life in miniature."

After getting the rights, Katz next needed to find a development partner to help put the two games together. It was at that point that he thought of Eddy Goldfarb.

"I had worked with Eddy when I was at Mattel, and he was one of the most prominent outside developers [there]. He developed ‘kids action games’, knew Barbie and Hot Wheels, and had employees who knew programming and had game design skills."

"Video games were just beginning and I wanted to test it out," Goldfarb, who is now 101 and living in a retirement community, tells us over a call. "I was very big in all kinds of toys and games. So, [...] I got the okay to go ahead with Barbie and Hot Wheels. I thought games based on popular toys might be very interesting. And then Barbie, of course, and Hot Wheels were very, very popular and I had a very good relationship with Mattel [...]"

Before Barbie for the Commodore 64, Goldfarb was primarily known for inventing classic toys, like the Yakity Yak chattering teeth, the children's game KerPlunk, and the miniature car Stompers. The businessman was one of the most respected figures in the toy business, having gotten his start in the industry all the way back in the 1940s.

"I was on a submarine during World War II," he tells Time Extension. "I was in the Navy for three and a half years during the war, and when the war in Germany ended, I felt like I better start thinking about what I wanted to do when we finished the war with Japan. I decided on the toy industry because I had no money and I wanted to be independent — I didn’t want to work for any company – so I started designing toys while I was on the Batfish submarine during World War II. I designed three educational toys, not realizing that the one category that the toy industry wasn’t interested in was educational toys [...] My first big hit toy might have been Yakity-Yak teeth with Irwin Fishlove & Company. The Yakity-Yak is the chattering teeth. They’ve lasted all these years."

Video games were just beginning and I wanted to test it out. [...] And then Barbie, of course, and Hot Wheels were very, very popular [...]

Despite being known predominantly for toys, Goldfarb started showing an interest in electronic games in the late 70s. In 1977, he attended one of the earliest electronic game conferences, Gametronics, which is where he met the software programmer Steve Beck of Beck-Tech. With Beck, Goldfarb later worked on a number of electronic games and also some video game titles for the Atari VCS, before eventually deciding to establish his own software department at his company A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates in the early '80s.

Among those he hired for this new venture were Kevin Kenney, Larry Irvin, and two women programmers (who we've unfortunately struggled to identify). Goldfarb wasn't directly involved with the actual development of these games, but instead, put his faith in the talented team of programmers to do a good job and complete the projects on time.

Larry Irvin joined A. Eddy Goldfarb Associates in 1982. He tells Time Extension, "I think there was a lot of trust. He was physically in a different building. His brother was actually in our building. He was a finance guy. So we didn’t see him that frequently. So I don’t know how much he was involved up front in the direction, but day-to-day he was not that involved. He was relying on the programmers. Again, it was a new world to him and to all of us. We were players of video games and he was not."

The World's First Virtual Doll?

In the first few years following the formation of the software division, the company produced several video games. This included an unreleased arcade game called Stamp Them Ants for Mylstar that was focused on squashing a colony of pesky ants that had interrupted a picnic, as well as a couple of ColecoVision titles, such as a port of Congo Bongo. Barbie and Hot Wheels, though, were set to be the biggest games the company had undertaken yet.

The programmer Kevin Kenney took the lead on Hot Wheels, while the two women in the department started work on the Barbie video game. It was Irvin's job initially to assist both groups, but when the women in the department left during the project, he had to assume control of Barbie and help steer the project forward. As Irvin tells us, this wasn't an easy task, not least because he didn't quite understand the strange naming convention that the two programmers had come up with for the variables in the code.

"They were Chinese," says Irvin. "So all the comments in the code were not readable. I didn’t understand them. And the naming conventions for variables were non-intuitive because it was them using English words but not with the comfort of the [proper] context."

It took a while to untangle the code, but eventually, Irvin got a handle on the project. At its heart, Barbie is a dress-up game. It begins with Barbie receiving a call from Ken asking her on a specific kind of date (playing tennis, visiting the gym, going to a pool party, a picnic, the prom, or a fancy dinner). The character then hops into a sports car, allowing players to visit various stores to mix and match outfits, colours, and hairstyles to assemble an appropriate outfit for each activity. If they style the character correctly, they'll see a picture of the date in progress, but if they don't, there's no penalty. Instead, Ken will simply call Barbie back and make a change of plans.

Truth be told the game's premise isn't the most complicated in the world, but the ability to dress the character in bizarre combinations — such as a full-length ballgown to go play tennis — provides plenty of room for experimentation and is made even funnier by having Ken ghost Barbie and reschedule their plans if he doesn't like her outfit. This inevitably provided us with a few laughs as we played, but it isn't what fascinated us the most about this old game. No, that was the presence of digitized speech, something which wasn't particularly common to find on the Commodore 64.

As Irvin recalls, "A decision was made on Barbie that was fairly significant, and I’m not sure where it came from: if Eddy was involved in it or not, but it was to add speech. Nobody was doing digitized speech on the Commodore 64 at the time. So, It was very difficult. Those machines didn’t have the ability to play video, plus memory was a limitation, so most of the sound effects were manipulating the frequency modulation of the sound chip.

"I had to find out how to do that and mimic speech," Irvin continues. "So I would record some audio and digitize it and then that’s basically 8-bit data that I have to use to twiddle with the sound chip. But then that’s a lot of data, so then I had to come up with a way to compress this and then uncompress it in real-time in a fast enough way to play at [the correct] rate. That was a monumental challenge."

The end result may come across as rudimentary today, but for the time it was an incredible feat, with the voices being more organic and human-sounding than many of the similar attempts we've encountered from other Commodore 64 titles.

The Response From Critics

It's at this point, you're probably wondering how critics at the time responded to the game. Well, from what we were able to gather, Barbie received a bit of a mixed response.

When the game was first unveiled in June 1984 at Chicago's Summer Consumer Electronics Show (alongside Hot Wheels), the press reacted enthusiastically to the idea, with the game being covered in the Chicago Tribune, The News Journal, and The Boston Globe, among other publications. It was later released sometime in the Winter of 1984, but reviews didn't start appearing until the following year.

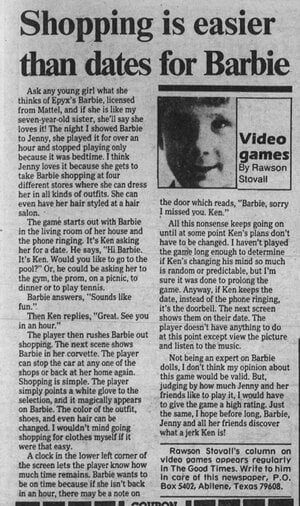

The earliest review we found came courtesy of the Vid Kid, Rawson Stovall. Stovall was one of the first syndicated game journalists, despite only being 11 when he got his start. In his review, printed across various newspapers in 1985, he praised the game, basing his assessment on the reaction of his younger sister Jenny:

"Ask any young girl what she thinks of Epyx's Barbie licensed from Mattel, and if she is like my 7-year-old sister, she'll say she loves it."

Run Magazine's Marilyn Anucci, meanwhile, offered a much more critical review. She enjoyed the game's "rich, colorful, finely detailed graphics" and "unusually realistic sound", but highlighted what they called a "sexist" portrayal of the character, stating:

"Why can’t Barbie call Ken? Why can’t Barbie say no? Why does Barbie have nothing to do but shop? Ken calls, Barbie jumps. It took Mattel’s Barbie 20 years to come out of her box and enter the real world. How long will it take the computerized—technology progressive —Barbie?"

Disappointingly for Epyx, Barbie, much like the other games in the Computer Activity Toys category, didn't go on to become a mega-hit and has since faded somewhat into obscurity. Katz now blames the lack of marketing support for why the line failed, with the publisher not being able to reach its intended audience.

"We didn't have a lot of advertising and marketing dollars to create widespread awareness," says Katz, "And we didn’t get promotional support from Mattel or Hasbro or retail merchandising support from Toys R Us, Electronic Boutique, GameStop, Sears or Walmart. The best sellers at Epyx were [instead] the action, sports, and driving games - Jumpman, Summer Games, and Pitstop."

Interestingly, Barbie and Hot Wheels were also the last two games that A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates made, with the inventor moving Irvin and the rest of the programmers across to the toy department of the company.

As Goldfarb tells Time Extension, "I made those two games [and] it was like making a movie. It was something very different and time-consuming. It took a lot of time and a lot of people, and I decided that really wasn’t for me. They took so long to make and while I could be making one video game, I could come up with three or four toys. So, I decided to stay with toys, and I did, and I was very successful with them."

While still working for Goldfarb, Irvin assisted on a new talking toy of the Cabbage Patch Dolls and Wrinkles the Dog. According to Irvin, these both took advantage of the same digitized speech techniques discovered on Barbie.

Irvin tells Time Extension, "Wrinkles was a pre-existing little stuffed dog and what we did was made it a puppet and when you move the mouth, it would speak. There were sensors on the doll that could tell if it was upright or prone, and it would say things in context with how it perceived it was being played with. That did sell. Then, with Coleco, we made a talking version of the Cabbage Patch Dolls, which also sold. [...] All of that speech came from Barbie."

It would be easy to dismiss Barbie as insignificant today given how simple it appears on the surface, but it's an important piece of video game history. In many ways, it set the template for what a virtual doll could be, paving the way for an entire subgenre of games that followed.

Just to demonstrate how ahead of its time it was, it wasn't until seven years later that another company came along and made another game based on the doll, and took another five before developers returned to the same "dress-up" concept — that time to phenomenal success.